The History of Telephones in Blackburn

Introduction

Communications between persons separated by distance has occurred for as long as humans have populated this planet. Since prehistoric times communication has been by fire (beacons warned of invasion), smoke (signals used by North American Indians and even today the Vatican announces the election of a new Pope using a change in the colour of smoke) and drums. The Greeks and Romans used relays of messengers which were the forerunners of the Pony Express and Royal Mail. Only with the introduction of science did things begin to gather pace. Following on from the carrier pigeon and semaphore came the telegraph, predecessor to the telephone.

The Telegraph

The origins of mankind's efforts to harness science to communication date from the discovery of the magnetic properties of the lodestone at the beginning of the seventeenth century. The magnetic compass gave the first suggestion that it was possible to communicate over distance using a 'sympathetic needle' system (Galileo 1632). With the advent of electric science the pace quickened and scholars across Europe began experimenting with discharges of electricity, albeit from a Leyden jar or static electricity. By the early nineteenth century Britain had a crude form of telegraph in the form of mechanical semaphore, used to send messages from London to the main naval ports. These structures could be seen on most hilltops, particularly in the south where they were established as warning devices in the face of possible invasion by the French. Many of these sites are still today identified by the name of Telegraph Hill.

The discovery of electromagnetism in 1820 was the key that unlocked the door to the communications revolution. The first significant invention was the electro-mechanical needle system. On 12th June, 1837 Crooke and Wheatstone were granted a patent for the world's first electric telegraph. They obtained an order from the Liverpool and Manchester Railway to install a signaling system alongside the railway between Rushton and Chalk Farm in London. In the same year the electro magnetic relay was invented by Davy. The next significant milestone was the introduction by Samuel Morse of a series of codes using long and short signals which, when used with his invention of the relay (an electromechanical device) would strengthen the signal at intervals along a line enabling communication over longer distances.

The Press adopted the telegraph in 1844, ensuring the swift reporting of events. Progress remained slow however, and it was not until the 1850s that telegraphy was accepted as an indispensable component of the rapidly expanding rail network with its need for safety and good timekeeping. In addition to railway companies, industrialists began to link their head offices and factories with telegraphs. Instead of employing a trained telegraphist, many preferred Morse Code or the ABC telegraph, invented by Wheatstone in 1840 and, which transmitted characters instead of deflecting needles. The ABC telegraph remained in use long after 1900. By means of the Telegraph Act of 1868, the Government ensured that the uncoordinated practices of private telegraph operators achieved some uniformity, by means vesting sole rights to operate UK public telegraph services in the Postmaster General. By 1870, this process was complete, with all telegraphs transferred to state control. There were 2800 telegraph offices, of which 1800 were at railway stations.

Telegraphs were installed at post offices throughout the country, bringing a low cost nationwide public service. When the Post Office took over the telegraph service, the average cost of an inland message was around two shillings for twenty words. At transfer, the number of telegrams per year was under seven million. The cost was reduced to one shilling, and by 1885 the number of telegrams had increased to thirty million. In 1885 the Post Office reduced the charge again to sixpence for twelve words, resulting in fifty million telegrams being sent that year. It is not surprising that with such a thriving business, and a large investment in its telegraph network, the Post Office was somewhat hostile to the arrival of the telephone

The Advent of the Telephone

The rapid increase in telegraph traffic drove inventors around the world to experiment with new ways to speed up the transmission of messages. Alexander Graham Bell exhibited his new invention at the American Centennial Exhibition in June 1876. Bell demonstrated his device to the British Association in 1877 and, in the following year, set up the Telephone Company Ltd, to sell Bell telephones for use on private wires. The price for the two telephones was over ten pounds, at that time more than a years wages for a servant. Bell foresaw a great future for the telephone and believed that one day every home and business would have one. Now, over a hundred years later, his forecast was not far wrong.

The Post Office did not share Mr. Bell's vision of the future. A report of 1877 cited several reasons for this lack of enthusiasm, among which were the prohibitive cost of investment in cables, equipment and real estate, the inability of the public to cope with technical electrical equipment, and the prohibitive cost to the public. There was at this time of course an abundance of cheap labour in the form of messenger boys and errand boys, delivering countless messages by hand and by telegram. The Post Office had just begun to realise a good return on its investment in the telegraph system, and saw the telephone as an infringement of their rights under the Telegraph Act of 1869. In Blackburn, an example of the excessive cost of providing a telephone, or for that matter a telegraph line, between businesses was revealed when the Northern Daily Telegraph moved into new offices on Railway Road. The building had a pigeon loft on the roof so that the result of Blackburn Rovers games could be reported that evening in the Sports Telegraph

.

The Telephone Arrives in Blackburn

Less than two years after Bell's successful patent, the first telephone call was made in Blackburn: between two factories belonging to Messrs Hornby and company.

The following is an extract from the Blackburn Times of December 22nd, 1877:

“The important invention of Professor Bell was on Wednesday last, tested in the presence of one of our staff. For some time past there has been Telegraphic communication on the ABC principle between Messrs Hornby and Co's mill at Brookhouse and their manufactory at Bank Top and on the day named, the telephone was attached to the wire connecting the mills.

The test was conducted by Mr. Young, the representative of Mr. J. Ahern, the telegraphic contractor of the Royal Exchange, Manchester.

The telephone is almost the shape of a small mallet, the head being the size of a full grown orange. The head is scooped out to form a hollow and in the centre is a small hole forming the communication with the handle, close to the hole spoken of, is a thin plot of soft iron, which is made to vibrate by sound. In the handle is a small straight magnet and coil. To this coil at the bottom of the handle the telegraph wire is attached.

There are two telephones both precisely alike used one at each end of the wire, the application of the telephone to the wire is but the work of a few moments. In speaking, the telephone has to be held close to the mouth and in receiving it has to be put against the ear.

Though it is over a mile between Messrs Hornby's mills, messages were sent along this wire with distinctness and the voices of speakers at one end could be identified by the listeners at the opposite end. In one instance a general conversation in the office at Brookhouse Mills could be faintly heard at Bank Top and the noise caused by someone walking across the floor was also heard. It is however a mistake to suppose that every noise is gathered up in a room by the telephone and transmitted with distinctness to the opposite end of the wire. Unless attention is called by the ringing of a bell or some other provision, that the persons at one end of the wire wish to communicate with the other no amount of talking through the telephone will 'attract' attention but when attention has been secured messages may be transmitted with effect.

A necessary condition is that a person must speak in a loud and distinct tone and another is that there must be quietness in the room where the message is received.

The test, so far as it went, was a success but there is room for improvement.”

Thanks to the foresight of a prominent townsman and businessman, Eli Heyworth, Blackburn was to play a significant part in the development of telecommunications for the next twenty years. Eli Heyworth was the first manufacturer in the town to have a telephone connection between a mill, at Audley Hall, and an office in Manchester. From the cover of the earliest Blackburn Telephone Directory (1885) it can be seen that Heyworth was vice chairman of the Lancashire and Cheshire Telephonic Exchange Company Ltd.

Image of Early Directory

The National Telephone Company was formed on 10th March 1889, and Heyworth later became chairman of the Executive. It was he who persuaded W.E.L.. Gaine, then Town Clerk of Blackburn, to accept the post of general manager of the N.T.C. Gaine, at once set about buying other telephone companies and, having gained control of all but one company, negotiated terms with the government, which then purchased the undertaking.

Eventually in 1912 the Post Office took over the N.T.C., thus giving direct continuity of development, charging etc, until the British Telecommunications Act of 1981 separated the postal and telecommunications businesses, and established British Telecom as a separate corporation.

Blackburn's First Telephone Exchange - Manual

In August 1879 the Lancashire Telephonic Exchange Company was formed and began to build telephone exchanges in Manchester and Liverpool. This later became the Lancashire and Cheshire Telephonic Exchange Company and, in 1882, the L. & C.T.E.C. applied to the Postmaster General for permission to make alterations to the general instrument room of the Blackburn Telegraphic Office in order to accommodate the telephone exchange. The L. & C.T.E.C. was unwilling to pay the five guineas in advance for the accommodation, and the post office did not therefore grant permission. So, the first exchange was sited at 8, 10 and 14 Astley Gate. By the following year, the exchange had 100 subscribers and one trunk line to Manchester (telephone no. 251). It employed six operators who recorded all calls in a book, and a report was made out each week. By 1885 the number of subscribers had risen to 190, and, in that year, a provisional agreement was made with the Post Office for the connection of a single wire from the exchange to the post office, then in Lord Street, for the purpose of sending and receiving telegrams. The first switchboard was an Edison Slipper Board, soon to be replaced by several others in quick succession.

The first call from Blackburn to London (Edgeware), a distance of 215 miles, was made on Wednesday, 22nd January 1890 by a reporter from the Blackburn Standard. His report appeared in the paper on the 25th January. At the time it was the longest distance yet covered by telephonic connection in the British Isles. The call was connected at 4:30 pm and was routed via Manchester, Sheffield, Birmingham and, finally, to London. This is what the reporter recorded:

"The writer called Manchester and had a weather report in 'Cottonopolis'. Sheffield favoured us with a selection on the accordion and a cornet solo. The operator also volunteered to sing a Psalm, leaving the choice to us. We chose the 119th as it afforded plenty of scope for vocalistic display and musical variation, and Birmingham has not yet been spoken to. We switched off at the tenth verse, having the other hundred or so to be rendered in our absence.

Loss of tone was minimised by the plenipotence of electrical currents".

In 1889 a Condition of Tenure for Astley Gate was sought and obtained from Blackburn Corporation, to run for 21 years. Although the new Post Office on Darwen Street was opened in 1907, the exchange remained at Astley Gate until 1916. When the new manual board opened at the Darwen Street exchange, there were 15 operator positions.

Blackburn's First Automatic Exchange

On January 1st 1912 the Post Office took control of the national telephone system from the National Telephone Company. Once the first exchange opened in Blackburn, technological innovation and growth in subscribers continued at a steady pace. In the first year of opening the exchange had 60 subscribers, at the end of 1883 the number had risen to 100. By 1903, 500 subscribers paid a yearly rent of £10, with unlimited free calls.

When the three-storey Post Office building in Darwen Street was opened in 1907, it was designed primarily for the core of the business, namely the counter service which occupied the ground floor for customer convenience. The building was not designed to house an automatic telephone exchange. Once installed the heavy equipment was housed on the second and top floors, with the operators on the ground floor. The heavy lead covered cables had to rise to the top floor via a 50 foot shaft in the centre of the building. Forty cables occupying the shaft represented a dead weight of over six tons. After a few years the vertical cables began to 'creep' due to sheer weight and it became necessary to insert an 'S' bend half-way up the shaft to reduce creepage occurring at a rate of one inch every six years. By 1957 the structure of the building was in danger of cracking under the strain, and a massive sectional girder construction was erected to support the weight.

The exchange equipment was installed by the Auto-Telephone Manufacturing Company of Liverpool, using engineers from America. A special feature, employed for the first time in this country was direct automatic working between subscribers on two separate exchanges, Blackburn and Accrington. Eighteen junction circuits carried calls from Blackburn to Accrington, and sixteen circuits in the opposite direction. The capacity of the exchange in 1950, and prior to its closure in 1964, was 4,200 subscribers. That was the limit the building could stand for safety reasons. This meant that the remaining Blackburn subscribers had to be connected to a relief exchange, erected adjacent to the relief postal sorting office in Mason Street, Lower Audley. This exchange was given the name Blakewater.

Public Telephone Boxes

There was reluctance on the part of many municipal corporations to allow public telephone boxes to be placed on the streets of our towns and cities. Prior to 1924, when parliament first made known plans to erect 40,000 outdoor telephone kiosks, public telephone boxes were located in the main in railway stations or inside post offices. Thanks again to the foresight of Eli Heyworth, Blackburn witnessed one of the very first telephone boxes sited on a public highway. The box was rustic in appearance, very spacious and proved not only to be a good revenue earner, but also a good educator for the telephone service. It was placed at the busy tram terminus at Billinge End because it was felt this would be a most favourable position to catch the public eye. It was erected on private land, for which the NTC had to pay a small annual charge.

Telephone Box at Billinge

The clock above the door was the property of Blackburn Corporation and was used by the tramway officials for timing and regulating the trams. The police had a key to the door and were allowed to make free calls to the police station, in return for keeping an eye on the kiosk. The public entered by placing one penny in the automatic box on the door. Once inside, the public paid for local calls at call office prices by placing money in a box attached to the instruments. The kiosk was lit by electricity, the light being activated by a bolt on the inside of the door. Additional revenue was obtained by placing advertisements inside the kiosk. When first brought into use, the table and seats bought with the kiosk were left inside. On the first Sunday, four men were discovered by the police inside the kiosk, smoking and playing cards. The table and seats were then withdrawn. Under the watchful eye of the police, vandalism or misuse were non-existent. In the 1920s a standard design was introduced for kiosks, made of concrete with wooden doors. This design lasted only six years before a cast iron kiosk, designed by Sir Giles Gilbert Scott R.A. was introduced in 1927.

Blackburn Telephone Area

On the 1st January 1912, with the exception of just four local services, the Post Office took complete control of existing telephone services. Today, only Hull remains outside the control of British Telecom. With the takeover came rationalisation and the Blackburn headquarters was moved to Preston. Blackburn became part of the north-west district, under the control of Superintending Engineer, Thomas Edward Price Streche, who controlled the engineering aspect of the business with the aid of three sectional engineers based at Blackburn, Preston and Lancaster. There was a parallel organisation responsible for the commercial side of the business. It is interesting to note that operators were employed not by the new organisation, but by the head postmaster, and remained under his control until as late as 1969.

In 1936 the country was divided into seven regions, of which the north-west region was one, and included the whole of Lancashire and Cumbria. In 1938, what had been the north-west region based in Preston was again reorganised into three separate telephone areas - Blackburn, Preston and Lancaster- each having its own telephone manager who now had full responsibility for engineering, sales and commercial matters. Blackburn Telephone area was opened on 21st November 1938 with a total staff of 493, serving 39,000 lines and having an annual revenue of £40,000. Staff were originally housed in four buildings, eventually increased to six before the building of the telephone manager's office in Duke Street in 1963.

The buildings were:

Claremont, East Park Road Telephone Manager's Office

Oakmount, Shear Bank Road External Planning

Woodlands, Shear Bank Road Internal Planning

St, John's Lodge, Ainsworth/ Richmond Terrace Engineering

Griffin Lodge Accounts

Telephone Exchange Darwen Street Post Office

Auto Manual Echange (Blakewater 1950) Mason Street, Lower Audley

Kathleen Ferrier was the telephonist operating the P.B.X. at St. John's Lodge.

A New Telephone Exchange and STD

By the late 1950s, it was apparent the Darwen Street and Blakewater exchanges were fast approaching capacity. Subscriber trunk dialling (STD) had been installed at Bristol and the Post Office had plans to enable all customers to dial their own trunk calls without operator assistance. To make STD practicable, each exchange needed a unique dialling code prefixed by '0'. Blackburn was allocated 0254. The STD innovation provided further reason why a new exchange was required, as the existing technology was not advanced enough to enable trunk dialling to take place.

The Post Office already owned the triangle of land on which stood Darwen Street Post Office, the Grand Theatre, the Palace Theatre, a public house and a few shops. It was decided to demolish the grand theatre in Jubilee Street and build a five storey telephone exchange. The building had to blend into its surroundings, especially the Cathedral which would face the northern wall. This wall was built of Longridge stone and the builders were Melville, Dundas and Whitson Ltd of Glasgow. The cost of the building was £210,000. GEC won the contract to install the exchange equipment, at a cost of £512,000. The exchange opened at 1.00pm on July 30th 1964 with 9,500 customers - the combined capacity of the old exchange and Blakewater exchange. The Mayor made the first call by ringing the head office in London of Laing, the company engaged at that time in rebuilding the town centre.

Following the introduction of STD, it was not long before the Post Office turned its attention to overseas, with the intention of enabling customers to dial their own calls to anywhere in the world. As early as 1891 telephone calls to Europe were possible, in particular to France with a direct telephone link between London and Paris. Little advance was made until 1951 when a new deep sea telephone cable was developed. In 1956 the first Atlantic cable was laid between Scotland and Newfoundland. During the 1960s, international direct dialling (D.D.) was available to Paris and America. The same decade saw the introduction of satellite led telecommunications. Just imagine how long it would have taken to link up the continents via deep sea cables. As U.K. telephone traffic increased, the trunk network became congested. In 1965 the Post Office tower was completed and soon became a vital link in the country's long distance network as well as for the transmission of television programmes. Technology was bringing rapid improvement compared to the relatively slow pace of the previous eighty years.

In May 1977 the United Kingdom became the first country to have direct dialling links with fifty countries. A further thirty countries were added over the next two years. It took until 1979 for customers in Blackburn to be able to dial their own international calls. To launch the IDD service the Post Office invited the Mayor, Councillor F. Hulme to make the inaugural call, at 11.30am, Thursday 29th March. The call was made to Lt. Colonel Ian St. Patrick Hurley, Commanding Officer of the 1st battalion, Queen's Lancashire Regiment, based at that time in Cyprus. It was fitting the Mayor chose to make this special call as the previous month the battalion had been awarded the freedom of the town. The Mayor's conversation was relayed over loudspeakers to an invited audience in the chambers of Blackburn Town Hall.

The photograph shows Mrs. Dilys Vallet (assistant supervisor) and operators Miss Vivian Green and Miss Sheila Abbott.

The jack units facing the operators were used to connect trunk calls from Blackburn and its surrounding districts.

The photograph shows Mrs Helen Clarke (assistant supervisor) and a group of operators.

The switchboard had a different layout to the one at Blackburn with the large subscribers multiple showing at the top of each position.

The exchange was opened by the Lancashire and Cheshire Telephonic Exchange Co Ltd.

The photograph above was taken in 1960 and is looking towards the top of King Street.

The site was then occupied by a Dancing Club.

Above is a photograph taken from a similar position in 1993 showing the site has been cleared and trees planted.

The Head Post Office on Darwen Street, Taken in 1964

Sources:

National Telephone Journal, June 1906, July 1907, August 1909 and 1911

British Telecom Journal, Autumn 1981, Spring 1984

Post Office Electrical Engineers Journal - 50th Anniversary Edition 1956

History of the Telephone in the United Kingdom. Baldwin

The first telephone call in Blackburn. BT Archive

Ring Up Britain. N. Johannessen

The 21st Anniversary of Blackburn Telephone Area. WR Beech

Blackburn - The Oldest Automatic Telephone Exchange- Post Office Telecoms Journal. J.H Bonnard, 1964

Opening of Blackburn Telephone Exchange 1964. Blackburn Reference Library

Blackburn to Launch International Dialling. PO Telecoms press release, March 1979.

Image- he Head Post Office on Darwen Street, taken in 1964.

K. Thompson

Published 2024. The original article was published in the Blackburn Local History Society Journal of 2000-1 page 7.

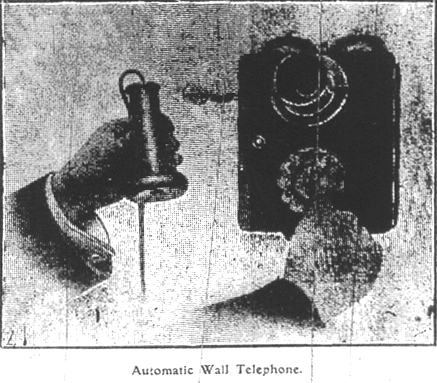

An article in the Blackburn Weekly Telegraph of 11th July 1914 gives the customer some instructions on how to use the “Automatic Telephone”;

“…we gave an illustration, which is here reproduced, of the automatic telephone and directions as to its use. As it will soon be in hundreds of Blackburn premises, a summary of these instructions will be valuable. Attached to each automatic telephone is a dial switch, and to call another number is a simple matter. Suppose, for instance, one wants to call No. 294. Having removed the receiver, the caller would insert a fingertip in the hole opposite the figure “2,” rotate the disc clockwise as far as it will go, and withdraw his finger. He then repeats the operation with his finger inserted opposite “9,” and again opposite “4.” That done he would be through to 294, whose bell is automatically rung, and who should immediately respond by lifting his receiver also. Then the two can converse. It will thus be seen that the operation takes but a few seconds, and any further delay is due to the called subscriber falling to answer his bell. If the number required happens to be engaged the fact is communicated to the caller by a vibratory current or buzzer signal which can be heard in his receiver…”

Published May 2024

back to top