Article from the Blackburn Times of March 2nd 1901

THE GREAT WASHING DIFFICULTY

VISIT TO A BLACKBURN LAUNDRY

BY OUR SPECIAL COMMISSIONER

Badly-washed linen, improperly-ironed shirts, damaged collars, torn frocks, iron-moulded sheets, demands for the value of soap which cannot possibly have been used and late deliveries on a Saturday night of damp underclothing which should be ready for use on the Sunday Morning—these are a few of the worries which embitter marital relations and render miserable the life of the householder who entrusts his weekly wash to the care of the average British washer-woman. Too often the clothes are washed in a backyard, or in an insanitary kitchen and after being pounded nearly to bits by the “dolly” or scrubbed into holes on a perforated zinc plate with the aid of a stiff brush, they are hung out to dry in the smut-laden air of a backyard in a factory-infested area of the town, and afterwards passed in thick bundles through a badly-adjusted mangle which nearly completes the work of devastation begun in the dolly-tub. Then the things to be starched are passed through a guess-work mixture of cold or hot starch, and are then ironed, for which purpose a box iron is used with heaters from the fire, or evil-smelling gas or coke. The heat is constantly varying, the iron is passed over the linen a few scores of times, still further damaging the material, and finally, the linen is put on one side to be sent home sometimes so stiff that it cracks when it is bent, and sometimes as soft as if it had never known starch; at one time bluey-white, at another yellow-white, but always lustreless and in a state which too frequently leads to family jars, especially when the exasperated husband begins to make cutting comparisons, to the beloved partner of his bosom, between the state of his own collars and those of his neighbour Smith, who sends his linen to laundry where they thoroughly understand their business, and have the necessary appliances to treat it properly.

It was in the middle of some such thoughts as these the other day that I received an invitation to pay a visit of inspection to the Rosehill Laundry at Higher Eanam. I gladly availed myself of the invitation, for I was curious on one or two points affecting public laundries, and wished to see for myself what warrant there was for the claim that they do not damage the linen &c., entrusted to them to anything like the extent it is damaged even in the most careful household.

In the first place I was asked not to go to the laundry until Tuesday morning, for the reason that the ironing does not start until then. The average British housewife is incurably committed to the practice of changing everything at the week end, and such a thing as having an extra set of linen in reserve, so that one lot can be taken to the laundry at some other time than Monday or Tuesday, never enters into her calculations. The result is that the public laundries cannot begin much of their business as a rule until Tuesday. The beginning of the week is taken up in collecting the goods, and the end of the week in distributing them. This habit for the British people is responsible in a measure for the somewhat high charges of the laundry keepers.

“If we could get people to send us their linen at the end of the week,” explained Mr. Stansfield to me, “so that we could employ all our people on the Friday, and on the Saturday and Monday, we could afford to reduce our charges. But they are bound to remain at their present figure so long as the machinery and the workpeople are idle half the time.”

I was told that it is not easy to get suitable “hands” in the laundries, for apart from the fact that the wages are not quite so good for the reason above stated there is a curious prejudice against them in factory districts. Women employed in them are looked upon by the factory girls in the same light as the charwoman who earns her living by going out washing. For the factory girl regards herself as a step above this kind of thing, consequently the young women are somewhat hard to get for work in public laundries. This statement only increased my anxiety to see what the work was really like in one of these establishments.

The laundry I inspected on Tuesday was erected from the designs of a local firm of architects. It is a square built block, for all the world like a lofty weaving shed in appearance, lit throughout by electricity. The receiving yard for the covered vans bringing in or taking out goods is in the centre of the front. Behind, at the top of a flight of steps, is the office, overlooking every department of the work. On one side of the yard are doors admitting the linen baskets from the collecting vans in the receiving room. Here the goods are separated, examined, and where necessary marked. They are next taken into the wash-house, where they are put into large revolving cylinders. Each cylinder contains the requisite quantity of soap and water, varying in quantity, quality, and temperature for the particular class of goods being washed. This mixture is renewed two or three times, and the clothes are rinsed several other times in perfectly clean water. All the metal work about the cylinders is copper, to avoid the possibility of iron mould. After the clothes have been washed—and they are as white as snow when they have been in the cylinder the requisite length of time, which is always carefully measured—they are put into a perforated copper drying pan which revolves at the enormous rate of over a thousand revolutions a minute. The water is drawn of through a pipe, and when the clothes come out of this pan they are nearly dry. The ordinary things are then hung up in a drying room adjoining where they are thoroughly dried in a strong current of filtered fresh air heated to a temperature suitable for drying flannels and woollens. They are then ready for the finishing processes in the ironing room. But starched goods require a good deal more treatment. After a shirt, say, has been washed and dried in the pan, the front, cuffs and neckband are passed repeatedly between Indiarubber rollers, heavily charged with hot starch. In this way the linen gets thoroughly impregnated with the mixture. The wrinkles are carefully taken out; the shirt is hung up on a drying-horse and run into another drying room very much hotter than the other where the starch is thoroughly dried. The shirt is then brought out and taken into the ironing room, where, after being dampened again, the cuffs are ironed by one machine, the front by another, and the collars by a third, by passing over them cylinders heated with a mixture of gas and air. Everybody who wears shirts of this description knows that unless the ironing is done very carefully the button holes in the centre of the front are never opposite each other—a most annoying fault, especially in a dress shirt, the front of which is almost certain to fly open and to crease when treated in this way. By the system I saw in use, this drawback is avoided. I examined a large number of the shirts, and in every single instance saw that the holes were exactly opposite each other. After an examination to see that everything is right—if it fails to pass the article is sent back to the damper again and re-ironed—the shirt is dried again, folded, and conveyed into the despatch room where it is quickly added to the other goods for the same house, folded up, put into linen-lined baskets, fastened together with copper wire, ticketed, and made ready for delivery by road or rail, some of the parcels, by the way, going long distances, even as far as Hull. The despatch room is kept warm, so that not a suspicion of dampness hangs about any of the goods, which are absolutely ready for use when they leave the premises. Flat things such as table linen and sheets, are also ironed by machinery and much more evenly than they could be ironed by hand. The more fancy articles with frills, &c., have of course to be ironed by hand. The irons used are heated by a mixture of gas and air. All the machinery is driven from a shafting underneath the floor, and there are no pulleys or belts visible and there is no danger of oil marks. Curtains after being washed are stretched on frames with silvered pins in a room above the drying-room and heated by air coming from it. Flannels are washed in a manner which ensures the maximum of cleanliness and minimum of shrinkage. I examined several flannel garments in the finishing room, and I was struck by their pleasant softness.

The system of ventilation is quite unique. There are double doors to every place of exit in the building, and air is drawn into it in the basement by means of two powerful fans. But it only gains admission by passing through a novel filter bed consisting of thick, closely-woven Navy blankets cut into breadths and sewn into funnels, one end of which is made up and the other left open and fastened into a kind of trellis work in the outer wall of the building. These woollen pipes are frequently removed and washed free from impurities. The result of these precautions and extraction of foul air by means of other fans near the roof in the main building is that the atmosphere is absolutely free from smuts and pure and pleasant in every room.

In going over the work, the technical part of which was kindly explained to me by the manageress, and Mr. Stansfield, I raised several questions, among them the impossibility as it seemed to me, of the average working man with 30s a week using a laundry like this and saving his wife the trouble and himself the annoyance of the weekly washing in a two roomed cottage in winter time with the necessity it often involves of drying clothes in front of the fire. I was informed, however, that a great many workingmen use the laundry. I gathered that the town was divided into districts and each district for convenience of working was treated separately. Goods in Preston New-road say are collected on Monday and delivered on Thursday; in another district they are collected on Tuesday and delivered on Friday, and in a third district they are collected on Wednesday and delivered on Saturday. As from first to last all the linen in this laundry is subject to the gentlest of treatment it must last a great deal longer than it does under the rough handling it ordinarily gets, and no doubt customers find that this and the inconvenience they are saved are important set offs against what may be regarded by some people as the apparently high charges of public laundries.

The history of the Crown hotel that once stood on that part of Victoria Street now covered by the Mall has a close affinity with Blackburn’s market. The old market which stood on the junction of Church Street and Darwen Street for hundreds of years had, by 1824, become inadequate for the town and was beginning to cause many inconveniences, Baines in his “History, Directory, Gazetteer of Lancashire” says; “The want of a good spacious market place is much felt in Blackburn, and the confusion and danger which prevail in the town on market days from the deficiency of room to carry on the necessary traffic incident to a place of this magnitude are very striking to strangers…” It was necessary for Blackburn to get a new Market; however, it was not until 1843 that things started to move in that respect. On March 3rd 1843 a report was made by the New Market Committee and sent to the Blackburn Improvement Commissioners, they wanted authorization to buy from the Feilden family, land in “the Tackets” for the site of a new market place. In 1845 plans were made for the Market House and Market Place, the design of the Market House being by Terence Flanagan and the building work by Robert Ibbotson of Blackburn. The cost of the project was £9000 and it was opened by William Hoole Chairman of the Commissioners, on January 28th 1848. The new Market was to the west of King William-street (originally called Livesey Street) with Cort Street running off the eastern side. Apart from some old buildings on the south side and a few more on the southeast side there were no other structures close to the new Market. The only Public house in close proximity to the site was the Hay Market Tavern in Cort Street.

It was felt by some, that a meeting place was needed for the market stallholders to go to for refreshment and to do business. Thomas Briggs, who was an enterprising man, saw an opening for such a place near to the new market. His family had, for many years, been landlords of various public houses in the town and so the obvious type of meeting place for him was a pub. The 1841 census shows Thomas Briggs as a landlord living on Northgate, though the pub he ran at the time is not named. In 1854 records show him being the landlord of the Masons Arms, which was to be demolished in the 1930’s to make way for the co-op emporium. Thomas, then, had had a good grounding in running public houses, and he decided that his next venture would be to build his own, the advantages of doing this were many, for instance with no other property around he could, more or less, choose his own location near to the market and the design of the building within reason could be one that would suit him. As to the location, he made a good choice, at that time Victoria Street was not yet laid out, the entire west side of the Market was free of buildings. Thomas bought some land on this side, and in 1855 building work began. It was three-story high with a mixture of brick and stone being used, not the most elegant of buildings but very practical. The doors of the Crown Hotel were opened for the first time in 1856, but Thomas’ tenancy of the pub was to be short lived, while walking down the street he suffered a stroke and died almost immediately. The date was September 30th 1857, less than twelve months after the opening of his dream. His widow, Betty, continued to run the pub and with great success for another 30 years until 1887. In that time Mrs Briggs saw many changes in and around the Market. Victoria Street was laid out and joined with Church-street; shops were built and opened on both sides of the Hotel. Joseph Feilden had laid the corner stone of the New Town Hall on October 28th 1852, about three years before Thomas had begun to build his pub, it was opened by William Hoole the Mayor of Blackburn on October 30th 1856, the same year the Crown opened. The Cotton Exchange opened in 1865. The Crown Hotel now had an elite set of buildings for neighbours.

When Betty Briggs retired the licence transferred to her son-in-law George Kemp, who had married Betty’s daughter Catherine Briggs. They ran the pub until late 1889 when John Rutherford (later Sir John Rutherford brewer, and MP for Darwen) purchased it. On February 6th 1890 the licence was transferred from George Kemp to James Houghton. He was the tenant selected by Mr. Rutherford to run the Hotel. After nearly forty years then, the Crown Hotel had finally gone out of the Briggs Family. It was because of the market that the Crown Hotel was built in the first place and the market, in a way, was responsible for its destruction. For many years market stalls had been supplied with gas from a meter installed in the cellar of the Crown Hotel. Although the gas supplied came from the corporation, the stallholders owned the meter itself. The stallholders had paid George Kemp £1 per year for keeping the meter in his cellar, but when James Houghton took over as landlord he stopped doing this.

The man in charge of looking after the meter, collecting rents and paying the Corporation for the gas used was George Ormerod who was a draper and stallholder on the market. It was also his responsibility on market days (Wednesday and Saturday) to see that the gas was switched on in the morning and off again at night. However, on Saturday, as the market didn’t finish until 11pm, Ormerod had come to an arrangement whereby Mr. Houghton would switch the gas off that night. In August Mr McMyn, who was the gas rent collector for the Corporation, told George Ormerod that the Corporation had decided to do away with the large meter in the Crown cellar and that the gas was to be cut off on the 30th of September. After that date, he told Mr. Ormerod, each stallholder would be provided with their own meter and would be responsible for paying their own bills. On the 1st or 2nd of November Luke Kearsley, the foreman meter inspector for the gas department of the Corporation, was given instructions that the meter was to be plugged or as they called it “caulked.” Two men, Thomas Poulton and William Smith were sent to plug it. Poulton explained at the inquest how they went about plugging the meter. “We took, mixed together, some tallow, white lead and red lead, made into a stiff putty, and Smith had a lump of waste [cotton cloth] in each hand, and was ready directly I took out the tap to stop the escape of gas with his hands on both sides of the hole. I plugged the tap with the tallow and red and white lead… I then popped it back in its place…we tried all the joints…we tried it with a blazing pitch rope.” Poulton then informed James Houghton, that they had “plugged the tap so that no gas could come to the meter.” He went on, “I should not say I had cut it off, for I hadn’t.”

George Ormerod was owed money by some of the stallholders for gas used, he therefore decided to recoup some of his losses by selling the meter (legally, it was owned by the stallholders); he therefore approached Mr McMyn and asked him how much the Corporation would give him for it. After consultation with his superiors at the Town Hall, McMyn offered Mr. Ormerod 10s (50p). Ormerod thought this a “ridiculously low price” and told McMyn, “Before I will take that price I will go and take the taps of myself and break it up for old iron.” A couple of days after this Ormerod was offered £1 for the meter, by a man called Mark Robinson, a 32 years old fruitierer with a stall on the market which he accepted. Mark Robinson lived at 8 Old James Street Blackburn. He and George Ormerod went to the Crown Hotel on Wednesday November 25th and over a glass of beer discussed the removal of the meter with James Houghton. It was decided between them that the best time to remove it would be the following Monday November 30th. Houghton had told them if they could get the meter into the cellar lobby, there would be a beer delivery the following day and the draymen would hoist it out. That Monday, Mark Robinson together with his brother Francis Robinson went to the Crown to remove the meter. Mark Robinson was under the impression that permission had been given for the meter to be removed, and that the gas to it had been cut off. Having acquired some tools and with a borrowed spanner the two brothers began to disconnect the meter, however finding the spanner too small, they used a hammer and chisel to loosen the joints of the tap. It was now that things began to go wrong for the Robinsons. With one of the joints loose Mark Robinson became worried because he could smell gas, going up stairs he said to Houghton “Jim come down in the cellar and just look at yon. I think there is gas.” Houghton assured him that the men from the Corporation had cut off the gas, and it must just be residual gas left in the pipe. This convinced Mark Robinson and he went back to the cellar. Now they began to unfasten the other side of the tap, Mark Robinson said “my brother had only just commenced to start the other union…it only needed a slight tap with the hammer and chisel to slacken the union, when the gas came in full force… the candle was on the top of the meter and there was a slight blue blaze, like gas and air, but just one waft blew it out.” Francis Robinson gave a slightly different account. He said “I was undoing the inlet joint when a little blue flame appeared. We blew out the fire, and finding this was nothing serious went on with the work and took of the union. I stepped on the meter and hit the second union two or three times when my feet slipped. My brother said he would jump on [the meter], and directly he got up I felt the gas coming up the side of my face. I told my brother to put out the light.” Both brothers now ran out of the cellar shouting to Houghton to turn all the lights out and open the doors, as there was a lot of gas escaping. Mark Robinson ran to the Gas office at the Town Hall, which was about 100 yards away. There he spoke to Robert Byrom, a clerk in the gas department and said “I want you to send a man to the Crown Hotel cellar. I have been uncoupling a large meter and the gas is rushing out.” Byrom asked if he could not knock the pipe up Robinson told him it couldn’t because it was iron. He then asked if it could not be plugged but was again told no. Byrom telephoned the “No. 1 gas works” in Jubilee Street and asked them to send a man to the Crown Hotel immediately as there was a large escape of gas, he told them there should be no delay as it was serious. A few minutes later, at about four o’clock, while Mark Robinson was still in the gas office the explosion occurred. Virtually every shop around the Market square was damaged; many had their windows blown out.

It was reported that the explosion was heard as far away as Billinge on one side of town and Shadsworth on the other. Francis Robinson meanwhile had also run out of the pub. He ran across the road to where two men were talking, Frances said to them; “We have made a bonny job of that, we have been uncoupling a meter in the Crown cellar, there is an escape of gas and we can’t stop it.” One of the men was in a horse and trap and left the market square, he was to tell the inquest that he returned about ten or twelve minutes later and stopped about four yards from the hotel and alighted from the trap, it was then that the explosion occurred, his horse took fright and bolted down Victoria-street it was stopped with some difficulty but was not hurt. It would seem then, that the explosion happened just over ten minutes after the Robinson’s first noticed the leak.

The explosion caused the front of the Hotel to be totally destroyed, all the furniture and fittings were smashed and sheets of flames shot up from the leaking gas pipe at the front of the building, igniting wood and other inflammable material around this fire which was to hamper rescue attempts for a long time. For all the damage and destruction the Northern Daily Telegraph, reported that “despite such devastation a large aspidistra plant was recovered from the Hotel with not one of its stems broken.” The front of the six-penny Bazaar next door was also totally destroyed. The shops adjacent to the two buildings had been damaged. Some as far away as 70 or 80 yards, had their large plate glass windows smashed. Large shards of glass were scattered all over the market square some stuck into window frames and doors. Stock from some of the shops had been blown onto the pavement. It was thought that many casualties were avoided because the walls of the buildings had fallen inwards and not onto the pavement where there were a number of pedestrians passing by. A box full of papers belonging to the Crown Hotel was found on Corporation-street, which was about 100 yards from the explosion. One of the first people to arrive at the scene was the Borough Engineer J.B. McCallum. Seeing the destruction he straightaway sent for all available men from the Corporation yard. Later other men were brought in from Darwen.

It only took minutes for the police to arrive at the scene, and immediately they cordoned off the area, and constable was sent to Clayton-street to inform the Fire Brigade. When the Brigade arrived they very quickly set up their hoses aiming them at the flames, but the leaking gas made controlling the fire extremely difficult. Searching the ruins for any survivors at this time was impossible. Onlookers became agitated because it seemed to them no effort was being made to find survivors. Shouts went up from the crowd to turn the gas off at the mains, but when men from the gasworks arrived they found it impractical to do this for fear of causing more explosions. It was decided the only thing to do was to dig up the road, break the main pipe and fill it with clay. While the Fire Brigade kept the flames from spreading, the gasmen began to do this. It was almost seven o’clock before the pipe was found, broke and filled, immediately it was done the flames were got under control and the work of rescue could begin in earnest. As it became dark, lights which had been brought from various local engineering firms were erected to aid the rescue.

Minutes after the explosion six people were led from the wrecked hotel; they were all taken to the Victoria Hotel close by where their injuries were attended. However another ten people still remained trapped in the ruins. The job of looking for these was further hampered by the threat of falling debris, and heat from the fire. At about six o’clock the rescuers heard the voice of Mrs. Wilkinson coming from the ruins of the shop but because of the heat and flames they could not reach her. The only way they could get to her was to break through the wall of the shop next door to the bazaar. When a fireman reached Mrs. Wilkinson, he found her wedged between some stones and buried to the neck in rubble. The first thing she asked was if her husband was safe and when informed that he was she said “Thank God.” Although weak and badly shocked she was able to aid her rescuers by telling them how she was trapped. It was just after seven o’clock when Mrs. Wilkinson was finally removed from the ruins and taken by stretcher to the police station at the Town Hall. Her injuries though severe were not life threatening, she had badly injured her leg and was suffering from deep shock. After an examination she was taken to the Infirmary.

Thomas Lightbown, one of the proprietors of the bazaar, who was rescued just before Mrs Wilkinson, told his story of the rescue: “I was in the back premises of the bazaar talking with John Wilkinson, my partner. The first thing that attracted our attention was a strong smell of gas. We went down into the cellar to examine the meter, thinking that perhaps it had been turned on since Saturday night… Wilkinson went up and passed through the shop, leaving his wife and me talking before the fire. Just as Wilkinson left the shop a female customer [Eleanor Buckley] entered the shop…then all of a sudden there was a flash and a report, and we went down, the floor giving way beneath us. I was held fast with the exception of my right arm. Regaining consciousness I commenced working away at the rubbish, and although I had nowhere to place the bricks and other material as I removed it, I at length succeeded in freeing my other arm. All this time I could hear Mrs. Wilkinson’s voice to the left of me, and that of the other lady to the left of me. The latter appeared to be about a yard and a half distant. All was total darkness and I could see nothing. I heard the lady say she could not take her breath. She continued talking to me and praying, but I could do nothing for her. “Oh man,” she several times exclaimed, “do help me.” I replied, “Woman I am fast, I cannot stir a limb.” Gradually her voice grew weaker and weaker, until it ceased altogether, from which I concluded she had died from suffocation, especially as I frequently called to her and got no answer. All this time I could hear Mrs. Wilkinson. She, like the other woman had done praying. I spoke to both women, trying to encourage them to keep their spirits up saying, “We might be thankful we are as we are, and no worse. There’s always a chance whilst there’s life. My half brother James Dewhurst was the first to pull me out, after, after the rescuing party had dug around sufficiently…” Annie Eliza Banks said; “Myself, Mrs. Houghton, Maggie Makin, Jessie Stones and Mrs. Martin were all standing by the fire in the kitchen [of the hotel], we were about to have a cup of tea when there was a explosion and I dropped into the cellar and found myself in darkness. After that I cannot remember anything until I was led out of the building.”

Edward Grimshaw, the ostler, said he was in the lobby of the hotel lifting some floor boards to get at the meter as he could smell gas. He had no light and none of the lamps were switched on around him. He had just lifted the boards when the explosion occurred. Grimshaw was not hurt and he assisted in rescuing the women from the kitchen.

The landlord’s son, Rothwell Houghton said he was in the cabinetmakers shop at the back of the building talking to Mr Aspden when the explosion happened, masses of bricks and other rubble fell on the spot where a few minutes before they had been standing. He saw his mother jump through the broken kitchen window where she cut her hand. He ran into the kitchen and found Jessie Stones lying on the hearth, part of the fire place had fallen on her. Jessie’s clothes had caught fire. Together with the ostler Grimshaw they managed to douse the flames and get her out of the ruins.

Another of the injured was William Sanderson who worked at the Warwickshire Furnishing Company, Victoria-street. He gave a statement to the Blackburn Times; “I had been serving a customer in the shop and having no change went to the Crown Hotel to get some. Entering the hotel I could smell gas and said jokingly to the landlord, “What a smell of gas there is here, there will be an explosion before long,” Haughton replied, “Yes yon chump heads [referring to the Robinsons] have left the pipes off.” There were five people in the vault, but I only knew Jim Houghton, John Casey and James Patterson. Casey was sat on a bench by the window and Patterson was stood with his back to the fire. Immediately I had got my change I opened the door and while the door was in my hand the explosion occurred. I can remember being flung across the street and past a horse standing there, but little of anything else. I must have been flung on my back for I found the back of my coat covered with mud. The next thing I remember is finding myself in Feilding-street with my face bleeding. This is a quarter of a mile away from the explosion. A man I did not know...took me to Dr. Owen, in Birley-street and my injuries were attended to. Coming to wind my watch the same night I found it had stopped at five minutes to four, which no doubt was the precise moment of the explosion. My change and cap were lost; my coat was torn, and so were my trousers. My head was cut with flying glass, and my face much burnt. Had I not had the door open there is little doubt that I should have been caught by the falling building, and I should have fallen near Casey, whose body was burnt so badly.”

The newspapers gave examples of various people who had narrow escapes. At about ten minutes to four Mr. A.W. King, secretary to the Technical school was crossing the market square heading towards the Crown to collect some illustrations he had used in lecture given there the week before, he met a friend on the square who asked King to go to the station with him. At first he said he was busy, but finally agreed to go and it was as they were on their way that the explosion happened. Another man who was to give a talk in the Crown that same night should have been there preparing the room at the time of the explosion but had been delayed.

All though Mr. Houghton, was the first casualty to be found trapped in the ruins, he was to be the last rescued. Houghton spent over four and a half hours trapped in the cellar of the hotel; the rescuers could not get him out because of the fire and the wreckage surrounding him. He suffered greatly from the heat and at one point asked the firemen to spray his back with water, which they did, but so much water was getting to him he told the firemen to ease off as he “feared that he might drown.”

One of the rescuers of Houghton was Thomas Felton of the Brewery Inn, Mary Ann-street. Felton together with Constable Chadwick and William Chadwick made their way into the cellar, where they found the only way they could reach Houghton was from an adjoining cellar. They cut a hole through the two foot thick wall which Felton crawled through, he found Haughton trapped from the waist down between some barrels, which after much effort they managed to move. The rescuers found his shoulder was trapped by a box of porter bottles which they had to smash with a hammer. The three men then took hold of Houghton and P.C. Chadwick said, “Now lift either for life or death.” They managed to get back through the hole into the cellar at which point Houghton asked his rescuers for a brandy. He was taken by stretcher from the ruined building to the Police Station. Houghton was the last person to be rescued alive, now the gruesome job of looking for the bodies of the dead, which were known to be in the Hotel could begin.

By midnight a strong wind had got up, it was feared that the chimney stack of the hotel might collapse which slowed the work down. Having managed to prop up the chimney work began to remove the rubble so they could locate the bodies. At about one o’clock on Tuesday morning the first body, that of John Casey was found. The fire had completely destroyed the lower part of his body and the rest was badly mutilated. By 10.45 Tuesday morning, four more bodies had been located and taken to what was known as the “small court” at the Town Hall; by 12 noon all the dead had been formally identified.

The five dead were:;

Eleanor Buckley, aged 56, married of 1 Penzance-street, Mill Hill,

John Casey, aged 62, widower, 7 Canning-street, Nova Scotia,

William Fielding, aged 60, married, tailor, 15 Simmons-street,

James Patterson aged 43, married Scotch draper, 35 Langham-street,

Henry Smithson, aged 52, 5 Kings-road Livesey.

The eleven injured were;

Mr. Houghton, landlord of the Crown Hotel, severe shock,

Mrs Houghton, landlady of the Crown Hotel, badly cut hand and severe shock,

Thomas Lightbown, joint proprietor of Bazaar badly shaken,

Mrs. Wilkinson, occupant of sixpenny bazaar, leg injury and severe shock.

Jessie Stones, barmaid, burnt about leg and scorched,

William Dugdale, pork butcher, Whinney Brow, badly cut on face, bruised on legs and body,

W.H. Aspden, 78 Lancaster-street, cut thigh and severe injuries to head,

Maggie Makin, barmaid, severe shock,

Annie Eliza Banks, Barmaid, severe shock,

Edward Walsh, fruiterer’s assistant,

Edward Grimshaw, ostler at the Crown Hotel, severe shock.

Early Tuesday morning Mark Robinson went to the Police Station and surrendered himself At eleven o’clock the same morning Francis Robinson also surrendered to the police. They both appeared at the Borough Court charged with causing the death of Mrs. Buckley and others. After some discussion and against the police advice bail was granted to both men.

Alderman Rutherford, the owner of the Crown Hotel, informed the Chief Constable that he would pay the funeral expenses of all the persons killed in the explosion. This generous offer was accepted by the families of four of the deceased, but Mr Buckley refused saying he did not feel his position justified him in taking advantage of Mr. Rutherford’s generosity. Messrs King and Blackburn, King William-street were engaged to organise the funerals. The funeral of James Patterson took place on Thursday afternoon December 3rd, that of William Fielding and Henry Smithson on the following day. John Casey was interred on Saturday and Eleanor Buckley, after a service at the Wesleyan Chapel on Sunday the 13th was taken to Ashton under-Lyne for burial. Many people from Blackburn attended all the funerals.

The Inquest on the five dead was opened on Wednesday December 3rd in the Borough Police Court; the Coroner was Mr. H.J. Robinson. Mr. Riley represented Mrs Paterson and Mr. Buckley; Mr. Withers appeared for the police, Mr. Costeker appeared for Mr. Rutherford, the owner of the Crown Hotel and Mr. Crossley watched the proceedings on behalf of the Robinsons. The Jury having been sworn in had the gruesome task of examining the bodies. Because no mortuary could be found the bodies had been placed in what was known as the small court next door to where the inquest took place. Evidence on the identity and the state of the five killed was given, after the identification the coroner adjourned the inquest until Thursday December 10th at 2pm.

The coroner opened the adjourned inquest by saying “…As you are aware this is merely an inquest into the facts of the case, and there can be properly no cross-examination or re-examination of witnesses. I shall be pleased to have the assistance of any professional gentlemen before me in eliciting facts, but it is merely for eliciting facts and nothing else. And after the facts have been elicited I don’t allow gentlemen to make any address.”

Once again Mr. Riley represented Mrs Paterson and Mr. Buckley; Mr. Withers appeared for the police, Mr. Costeker appeared for Mr. Rutherford the owner of the Crown Hotel and James Houghton, landlord of the Crown Hotel; Mr. Crossley appeared on behalf of the Robinsons; Mr. Mattinson M.P represented Blackburn Corporation.

The witnesses were called and the events leading up to the explosion were given as above. One crucial piece of evidence was that given by William Sharples who was the foreman over the outdoor pipe-laying men. He had given Thomas Poulton and William Smith orders to plug the meter. When asked if he had ordered the meter to be plugged or cut off from outside he replied, “It is our custom to plug them until we know whether the meter has to be removed.” Sharples told the court, that if a meter is taken away permanently it is uncoupled outside and a blank end is put in if the pipe is of iron or knocked over if lead. He also told the court that he had not received any notice that the meter was to be removed or he would have cut the pipe off in the street. After Mark Robinson had given his evidence as laid out above Mr Mattinson said; “With regard to this witness, I should like to make this statement on behalf of the Corporation. I do not accept the evidence the witness has given. I say no more. The witness at present has a criminal charge hanging over him, and in my opinion it is not proper where a criminal charge is hanging over a man’s head, to subject him to hostile cross examination. I shall not cross-examine him, but merely wish to intimate that the Corporation do not accept his evidence.

Mr Crossley replied; “I think that that is a very improper observation. It rather suggests that the witness has not spoken the truth as far as his evidence affects the Corporation. He has given his evidence voluntarily, and if the Corporation can bring other evidence to contradict it, it ought to be produced to you, Mr. Coroner.

The Coroner said; “I make my own deductions from the statement.” Again after Francis Robinson gave his evidence, Mr Mattinson said; “What I said in regard to the other man I have to say in regard to this.”

The Coroner then began his summing up. He went over the evidence given by each witness. During his summing up he mentioned Section 15 of the Gas Works Clauses Act Of 1871 which he read to the court, this says “No consumer shall…disconnect any meter from any such pipe unless he shall have given the undertakers not less than 24 hours’ notice in writing of his intention so to do; and if any person acts in contravention to this section he shall be liable for each offence to a penalty not exceeding 40s.” Mr. Costeker interrupted and said that gas was not being supplied through the meter at the time of the accident and further the Act mentions “consumers” and as the Robinsons’ were not consumers then the act did not apply to them. The coroner replied by pointing out that as Mark Robinson was a market tenant he was therefore a consumer of gas. He went on to say that as no notice had be given to the Corporation in writing of any intention to remove the meter technically, the Robinsons had broken the law. However, he added that Mr. Ormerod had had a conversation with Mr. McMyn about the meter. Mr Ormerod had informed Mark Robinson of this conversation, it was up to the jury to consider whether Mark Robinson understood this as a waiver to the twenty four hour written notice rule, and he had been given permission to remove the meter. If they thought this then the case might resolve it’s self into one of carelessness. On the other hand the coroner said, “If they were doing what was unlawful they are guilty of manslaughter.” He gave a definition of manslaughter as follows; “Where in pursuit of some lawful act which is improperly performed and death ensues in consequence it is manslaughter. It is also manslaughter if an unlawful act is followed by death.” He finished his summing up by telling the jury; “The question for your consideration is whether the evidence you have heard will reduce the charge against the Robinsons to something less than manslaughter. As far as the two men are concerned there is no difference between them, and whatever verdict you find against one you must also find against the other. The only question is as to whether you can see anything in the evidence which will reduce the charge from one of manslaughter to one of accident. I think I have made it clear to you. It does not matter whether the gas came from this pipe or the other one. If it came from the disconnection of the pipes, and without notice having previously been given to the Corporation, it would come under the Act of Parliament. The meter had not been disconnected by the Corporation. These are the facts...You had better retire now...to consider your verdict.”

After some clarifications made by the Coroner the jury retired to consider their verdict. They returned after half-an-hour. The Coroner asked if they had reached a verdict, the Foreman of the jury replied; “Yes we have. We desire to express our heartiest sympathy with the sufferers by this explosion, and, after careful consideration of the evidence we are of the opinion that it is the result of a pure accident. The Blackburn Standard reports that “The result would have been received by applause on the part of the public in the gallery, had it not been for the demonstration which threatened to manifest being at once suppressed by the Chief Constable.”

The celebration for the Robinson brothers however was to be short lived. The day after the inquest Mark and Francis Robinson once more found themselves before the Borough magistrates. They were charged with causing the death of five people. Mr Withers prosecuted and Mr Crossley defended. Mr Withers said “At the inquest on Thursday the jury found a verdict of accidental death, but the Chief Constable felt that the case was of such magnitude and importance that it was his duty to bring it before the magistrates for them to adjudicate upon. After going over the evidence the Chairman of the magistrates said; “After careful consideration we have come to the conclusion that the case ought to go to a jury, and therefore the prisoners will be committed to the Manchester Assizes, on the same bail as before.”

Certainly the Blackburn Standard agreed with this finding. The paper said in an article on the 19th of December; “Upon the same evidence of fact, and the same statement of law, the jury [at the inquest] found the affair was accidental, and the magistrates committed the two men for trial on a charge of manslaughter. It is probably safe to suggest…that pity for the unhappy men was largely instrumental in evoking the merciful verdict of accidental death…The Magistrates, with more regard for the law than the Coroner’s jury (but not more than the Coroner himself,) have sent the men to trial. We fail to see how they could have taken any other course.”

The trial of Mark and Francis Robinson was set for Wednesday March 16th 1892 at the Manchester Assizes on the charge of the manslaughter of Eleanor Buckley. When it was brought before the court the Grand Jury returned a “No True Bill” [there is no probable cause to decide that a crime has been committed] against them. The Robinson Brothers were therefore discharged.

On Monday December 14th, at the Theatre Royal a performance was given by the Blackburn Amateur Operatic Society for the benefit of sufferers of the disaster. There was a very good house and the proceeds amounted to £47 3s 6d which was handed over to the Mayor.

Another benefit performance was given by a Mr. Transfield, the proprietor of the “New Circus.” It was reported that; “A special and attractive performance will be prepared, and half the gross receipts will be given to those who have suffered by the explosion.” The Blackburn Licensed Victuallers’ Protection and Benevolent Society held a meeting at the plough Inn, and resolved to send a letter to Mr. and Mrs. Houghton congratulating them upon their “remarkable escape from an awful death” they also sent a “heartfelt expression of thankfulness to the rescue of Mr. Houghton, “who is an esteemed member of our society.”

On July 13th 1892 an action was taken out by Jessie Paterson, the widow of James Paterson, for the loss of her husband. It was against Blackburn Corporation, and for £2000. The case was heard at the Manchester Assizes before Justice Denman; Mr Gulley Q.C. was for the plaintiff and Mr. Bigham Q.C. the defendant. The argument for the plaintiff was that Blackburn Corporation had been negligent in not having properly cut of the supply of gas to the meter. Mr. Gulley stated that the gas should have been cut off at the mains or the main pipe blanked off. He added that although the explosion had been caused by the Robinsons, that did not in any way absolve the Corporation from their negligence.

Mr Bigham told the court that there was not one shred of evidence of breach of duty on the part of the Corporation, and that no notice had been given by the Robinsons to the Corporation that they would remove the meter which was in contravention of the law, he also denied that the Corporation had given notice that the service was not to be used again. Mr. McMyn said that the gas was to be cut off he only meant that the supply to the stallholders was going to be cut off, this was in order to compel the stallholders to keep up the payment of their accounts, and the supply might be re-connected at a later date. After hearing all the arguments Justice Denman summed up, then the jury retired to consider their verdict. The verdict was for Mrs. Patterson and was for £600. On Friday at the Assizes it was agreed that Mrs. Patterson should receive £400 and her four children £50 each, with interest, when they became of age. Pending an appeal Mrs. Patterson was to have £50 and £1 per week from the Corporation.

An appeal was lodged by the Corporation which was heard on the November 29th 1892 at the Court of Appeal, Liverpool. It was before the Master of the Rolls and Lord Justices Lopes and Kay. Mr. Bigham said the claim for the case in which judgement was given was £600, but between £20,000 and £30,000 depended on the decision, seven people having been killed (a mistake on the part of Mr. Bigham as only five people were killed) and several injured.

After a long deliberation the appeal was dismissed, the court agreeing that there had been gross negligence by the Corporation in not properly cutting of the gas. The total amount of compensation paid out by the Corporation was £14,000 in. The money was obtained by increasing the price of gas by 3d per 1000 feet.

While the ruins of the Crown Hotel were being demolished, a crane collapsed, injuring two men. One of the men, Thomas Baywood sued Christopher Hindle, contractor for £75 for personal injuries received. The crane was being used to pull down a brick pillar when the jib and pivot of the crane gave way breaking Baywood’s right leg. The cause of the collapse was too much strain on the crane. The jury found for Baywood with damages of £52 8s being paid.

The explosion was reported not just in this country but throughout the world, some reports however were rather exaggerated. For instance, the Chicago Herald reported that the explosion had wrecked three buildings with an estimated death toll of 32. Stories of miraculous escapes were given, with much distress the same paper also said; “One poor woman with five children clinging to her skirts and a babe at her breast was the centre of sympathy and interest in the crowd. She was the wife of the assistant cook of the hotel, [who according to the paper had been killed] and her cries and those of her children were pitiful.”

By the January 2nd 1892 the site had been cleared and a wooden hut was erected as a temporary public house. It seems there was a charge was levied to enter this temporary public house. A few nights after it first opened the Blackburn Standard reported that “John Edmundson (42), agent, of 34 Brookfield-street, was fined 5s and cost for being drunk and disorderly in Victoria-street, on Saturday evening. Prisoner stood along with a number of others by the wooden premises recently opened as the Crown Hotel on the site of the runs in Victoria-street, and was shouting at the top of his voice “Free Admittance.” He afterwards found free admission himself—at the Police Station.”

The Crown Hotel was quickly rebuilt and was once again opened for business by late 1892 or early 1893 the architect of the new hotel was Walter Stirrup the contractors being Marshall and Dent. It had electric lights rather than gas installed and cost about £6000. Mr Hayhust, owner of the next door also built a replacement shop to the same design as the Hotel. The new building stood on Victoria-street for a further 72 years until it was demolished to make way for Blackburn’s shopping centre in 1965.

By Stephen Smith

Some Local Place Names

with

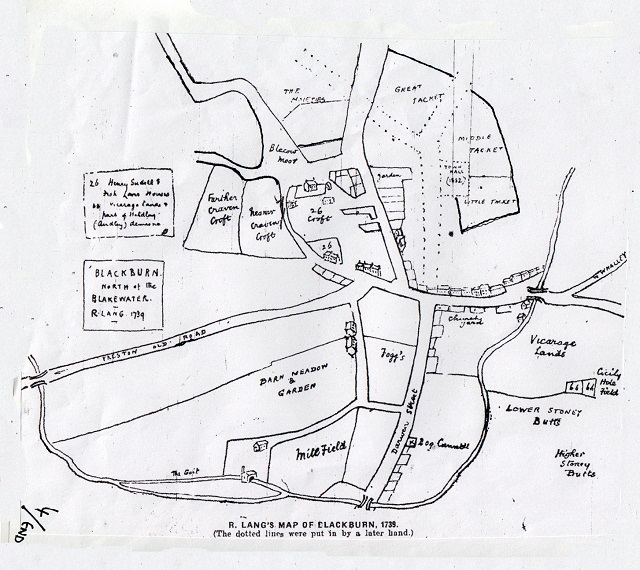

Plan of Blackburn in 1739

By

G.A, Stocks, M.A.

This article was written in 1908, some street names mentioned may not exist today or their names may have changed.

The modern fashion of naming streets has been adopted with a view to giving a hint as to their locality. Thus, we find in Blackburn of to-day (1908) a group of river streets such as Calder and Hodder Street. In another place we find names of trees, such as Cedar Street and Plane Street. When a town becomes big, such a nomenclature is convenient. In the plan maps of Blackburn in 1739 one may suppose that no great change had taken place for some centuries; that the fustian websters and others worked at the at the ancestral looms, and outside the town, were partly farmers and partly weavers. Some Blackburnians who have lived to see the twentieth century can recollect the trees beside the Blakewater, and the local magnate, Sudell, of Woodfold, driving down Shear Brow in his carriage and four.

In the Visitation of Henry VIII’s officers, given at the end of the Whalley Coucher Book, it is stated that all the town of Blackburn was the parson’s glebe. It was accordingly treated somewhat differently from the abbey lands. The churchyard, which originally did not extend so far south as the present church, was lined with humble cottages and a few better-built houses. One of these smaller hoses sold for £2 10s, and its yearly rent was 6d. Several “yarn-crofters” are also mentioned as paying 6d. rent. In 1687 Francis price, vicar, gives a list of poor persons who have paid 2d, 6d, and 9d, apparently as a “customary Fee” on entering into passion of the cottages. This fee was called “hearth money” by the poor. Vicar Price is firmly of opinion that none of his predecessors for a thousand years have received more from those tenants, and he avers that the houses are not more than 10s value, on average, “if set upon the rack.”

The Parliamentary survey of 1647 states, e.g., that John Sharples pays 6s 8d for a house which is worth upon the rack, per annum £4, and Jane Morris “holdeth a fair house by the school,” and pays1s 8d, the rack being in this case £1 13s 4d. it is well known that the Blackburn vicarage passed into the hands of Archbishop Cranmer, and from that time until 1847, when it apportioned to the new see of Manchester, it was a portion of the property and patronage of the Archbishop of Canterbury, situate in the province of York. Near to the Parish Church we are quite prepared to find ecclesiastical street names. Such are Cleaver Street–Cleaver was Bishop of Chester from 1788-1800. In the same neighbourhood we find Manner Sutton Street, which ought to be Manners Sutton Street, perpetuating the name of the Archbishop of Canterbury at the time of the re-building of the Parish Church, [1821-1826].

Another Archbishop of Canterbury who was previously Bishop of Chester, has given his name to Sumner Street, which lies appropriately near to Canterbury Street. The archbishop consecrated 143 churches in Lancashire only, and saw the advent of 671 new schools and 768,585 additional inhabitants in his diocese of Chester. The name Linney Yate, which is found as a name of a tenement, I think, in the Eanam neighbourhood, may remind us of old Ralph Linney vicar [of Blackburn] from 1536-1555. He retired, probably on account of his religious opinions, and lived for at least 10 years afterwards. Starkie Street reminds us of Thomas Starkie, our mathematician-vicar, 1780-1818. Syke Street probably marks the sight of an old water course. It is a familiar name, as a boundary or landmark in old documents. The Hallows, Upper and Lower, have frequently been referred to as the parcels of land that took their name from Hallows Spring. Two other springs were St Mary’s Well and Folly Well. The last named still is found as a street name, and the well itself, I am informed, exists in the cellar of one of the cottages in Follywell Street. Stony butts was a field-name somewhere between the railway station and Darwen Street. It is just possible that these butts may have been the place where the Blackburn bowmen shot at their targets, but the word “butts” is often used to describe rough hummocky ground, though we know from our own seventeenth century local literature that facilities were desired for practice with the bow.

Bastwell is a name found more or less disguised by spelling, since before the days of the Abbey at Whalley. I have seen it spelled Baddestwysel, date about 1280. Richard de Baddestwysel had a mill on or near the Blakewater, which he made over to the Abbey of Stanlaw, and in order that the water might not be intercepted on its way to the mill by any of his heirs, he gave “all his land lying in an angle, on the south side, etc., etc.” This deed is witnessed by a perfect parliament of Blackburn Grandees, De Blackburns, Fitton, Plesyngton, Billington, Livesey, Ruyssheton, Eccleshil, Grymeschagh, and others. This “angle” is interesting, because Bastwell bears the same relation to Bastwisle as Birtwell to Birtwistle. The mname ending—twisle—is held to mean an angle formed by the meeting of two streams of water. The word is derived from the same root as twi, two, twixt, etc. Thus, a Twig denotes the fork or angle of a tree, where the small shoot leaves the larger branch. This explains the first t in names like Oswaldtwistle, Entwistle. And son on. The second t is introduced upon a false analogy with “whistle.”

Oozehead and Oozebooth, seem to denote watery places, like the name Ouse, which is so common among rivers. “Booth,” like the Highland “bothy,” denotes a small homestead. In Rossendale the whole valley was covered with such tenements, and the termination “booth” is found frequently today. Abram shows how (p. 119 A History of Blackburn) “a husbandman by a by-name called Duke of the Banks” gave his name to that part of the road called Duke’s Brow. The same account mentions the old Tithe Barn at the N.W. crossing of Duke’s Brow and Revidge as being used to shelter “Priest, Jesuits and Papists” on the occasion of that fighting which is described in the place cited. Mill Lane marks the approach to a mill on the Blakewater. The mill was the property of the family of Baron “of the Mylne” for two three centuries. The small “cut” from the larger stream which entered it again near St. Peter’s Church, is marked on the maps as “the Goit.) Jubilee Street and George StreetWest, close by it remind us of the year 1610, the jubilee of King George III. Nab lane tells of a family called Nab or Nabb, whose names occurs sellers of wine and other things in the church in the churchwardens’ account books. Fish Lane perhaps Dandy Walk and Freckleton Street recall names of owners of property.

The 1739 map shows a “Dog Cannell” on the south of the town and a “Catchem” Inn on the Bolton Road. Other interesting inn names are the “Bird in Hand,” is this a reference to the days of Hawking? “General Wolfe,” “Paganini” in Northgate, “The Old Ring o’ Bells,” “Flying Angel,” The Higher Sun,” “The Legs of Man” in Darwen Street. This was probably a compliment to the Derby family, in whose coat of arms, as Lords of man, this device had a place. Negro’s Row is spoken of as a part of our town in the 19th century. “The Ould Cockpit” has been referred previously. “Lobs o’ th’ Nook” and “Lotty’s” are names of two old tenements. The former is marked in Shadsworth; the latter is connected with the family name of Tomlinson. “Blakeley” Moor is found, and I have heard the “Blakely” pronunciation quite lately. On the Mellor side of the latest Blackburn there is a farm called “Dick Dadd’s.” The burial register at the parish church shows us that the wife of Richard Sharples de Mellor, “Dicke Dadd,” was buried in February, 1622.

For a finale, is it possible that our “Wrangling” can be the old-time wrestling ground? As a matter of etymology, it is a fairly safe derivation. Perhaps some lover of our town and its ancient divisions will oblige. The name Revidge still remains unexplained, for neither “Rough Edge” or “Ridge” seem to carry conviction as a solution of the puzzle, though the parish history of Ribchester states that “edge” is a common name for a hill on this side of the Ribble.

Lang's Plan of Blackburn in 1739

back to top