MURDER IN THE HEATHER:

The Winter Hill Murder of 1838

David Holding

FIRST EDITION 1991.

SECOND EDITION 2017.

Copyright ( C ) DAVID HOLDING

The right of David Holding to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS.

It is always difficult to remember when undertaking research of any kind, all the people who helped along the way with advice, encouragement and information. I should like to express my thanks to those who played a pivotal role in bringing my original work from an initial concept to full fruition. To all these people I express my sincere and grateful thanks. My thanks also go to those anonymous but ever helpful staff at the numerous institutions and archives I have consulted. I would wish to single out for special thanks and appreciation the following:

Lancashire County Record Office, Preston.

Bolton Central Reference Library and Local Studies Department.

The Staff at the Harris Library, Preston.

The Staff at Blackburn Reference Library.

The Manchester Metropolitan University Local Studies Department.

Acknowledgement is also paid to members of both the medical and legal professions, for the benefit of their expertise on the various matters raised in this work. My gratitude loses no sincerity in its generality. I would however, hasten to add, that none of the above are responsible for the contents of this work, any mistakes are entirely my own.

David Holding 2017.

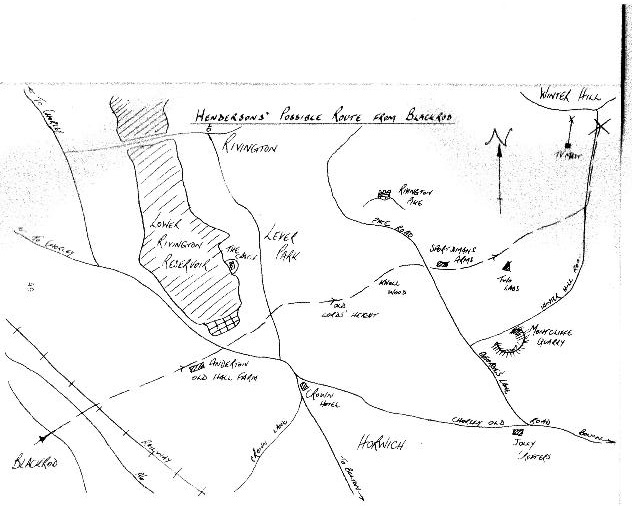

Area Map of the Incident.

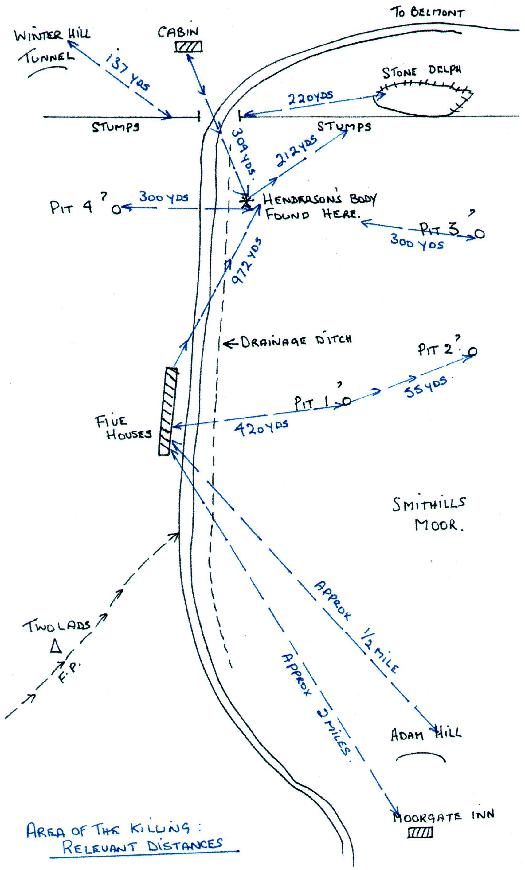

The North-East Slope of Winter Hill.

INTRODUCTION.

Winter Hill and nearby Rivington Moor are familiar landmarks to the inhabitants of the neighbouring townships of Horwich and Bolton, lying in the valley below. They present a challenge to the adventurous hiker who, after a struggle to the summit of Winter Hill some 1,475 feet above sea level, will have his or her efforts amply rewarded by the view it affords on a clear day. To the north-east can be seen the slopes of Pendle Hill and further still, the outline of the Yorkshire Dales.

The most direct route covering the area of our case is from Bolton along the B6226 Chorley Old Road, which was formerly the old Turnpike Road from Bolton to Chorley. Just before the road drops down towards Horwich, there is on the left-hand side the 'Jolly Crofters' Inn, and almost directly opposite is Georges Lane. This lane runs along the moor's edge towards Rivington Pike passing several stone quarries. The main working quarry today is at Montcliffe, which was a small hamlet with a colliery and miner's cottages. Bearing right past Montcliffe Quarry, there is a modern road constructed for access to the TV station and radio masts on Winter Hill. This road follows the original pack route over the summit of Winter Hill towards the village of Belmont, and then on to Blackburn.

In the early nineteenth century, there were several dwellings situated along the route over Winter Hill such as 'Five Houses', a group of terraced cottages, the Winter Hill Brick and Tile Works, and several small working coal pits, all owned by William Garbutt who resided at Five Houses. When excavations were being undertaken for the present television mast in 1959, old coal workings were discovered at a depth of some 50 feet. There were part of the Wildersmoor Colliery which was worked from the early nineteenth century until its eventual closure in 1961. At a distance of some 700 yards past the television mast, there is the site known locally as “Scotsman's Stump", where a simple memorial was erected to mark the spot where the victim of our case was discovered in 1838. It bears the following inscription:

“ In memory of George Henderson, native of Annan, Dumfriesshire, who was brutally murdered on Rivington Moor at noonday 9th November 1838, in the 20th year of his age".

“Scotsman's Stump".

Memorial Plaque on “Scotsman's Stump".

CHAPTER ONE.

Our account of the Winter Hill murder of November 1838, commences with the movements of one George Henderson, a twenty year old Scotch traveller, a native of Annan, Dumfriesshire. He was employed by a Mr John Jardine, a draper with a business in Blackburn as his traveller. Henderson moved around the neighbourhood stretching from Blackburn to the outskirts of Bolton, including surrounding small villages, selling goods, taking orders and collecting payment in return. It was his usual custom to make his way every other Friday back to Blackburn to report to his employer. This would take him on a regular route over Horwich Moor and Winter Hill to the village of Belmont.

He is known to have stayed overnight at the Old Cock Inn, in Manchester Road in the village of Blackrod on Thursday 8th November 1838. The following morning from the high vantage point of Blackrod, thick cloud could be seen smothering the nearby moors at Horwich and Winter Hill. It was in this general direction that the regular travellers' route to Blackburn ran, climbing up the moor and passing over the summit of Winter Hill, before descending to join the Bolton to Preston road near Belmont. About half a mile distance from the summit of Winter Hill and along the left-hand side of the road, stood a group of terraced cottages known locally as “Five Houses" or Garbutt's, after the owner of the cottages, brick and tile works and several local coal pits. Garbutt's own cottage also doubled as a beer-house which became a regular meeting place for both travellers and the local inhabitants of the area.

These travellers or 'packmen' were a common sight in the area during the nineteenth century, having migrated from Scotland to seek employment in the area. They often settled in small communities in many of the towns of the north-west of England. One such area in Blackburn was known as “Nova Scotia" or “New Scotland". A fellow Scotsman, Benjamin Burrell, himself a traveller from Blackburn and friend of Henderson, had arranged to meet him on the Friday morning the 9th of November about 11.00a.m. at Garbutt's beer-house. They were both due back in Blackburn on the Friday night, and had decided to have dinner together at the Black Dog Inn in Belmont, then travel back together.

Burrell had arrived at Garbutt's beer-house a little early on the Friday morning around 10.00am and he waited for his companion to join him until about 11.00a.m. Henderson not having arrived by then, Burrell left Garbutt's with a message that Henderson should join him later at Belmont for dinner. It is known that Henderson had left Blackrod on the Friday around 8.00a.m., with his pack swung over his shoulder and with a walking stick. His considerable delay in arriving at Garbutt's suggests that he may have had several calls along his route before eventually arriving at the beer-house around 12.00 noon. We are told that he did partake of a glass of ale which, according to Mr Garbutt, was a rare occasion for the young Scotsman. Having received the message that Burrell had left some time earlier, he made his way up the road towards Winter Hill summit and on to Belmont.

At a point along the road not far from the summit and just before the road descends through a gateway in the boundary wall known as the “Stumps", the unfortunate traveller fell victim to an horrific shooting from which injuries he subsequently died. It was later estimated that the shooting must have taken place between 12.-15 and 12-30p.m, although there is some speculation as to the precise time of the shooting. Henderson was still alive when a young boy passing the spot heard moaning coming from the drainage ditch on the right-hand side of the road. He did not venture to the spot because of fear of what he might find, but hurried to one the numerous coal-pits to raise the alarm. Returning shortly in the company of one of the local colliers, they both found the body of Henderson lying on his back in the ditch, having been shot through the head. The time would be around 12-45p.m, and with the assistance of other local men who had by now arrived at the scene, the victim was carried back down the road to Garbutt's beer-house, where he died about 2.30pm.

The body remained at Garbutt's for the post-mortem examination, and until the following Wednesday, when it was taken in solemn procession for burial in Blackburn. According to Mr Jardine, Henderson's employer, he was a young man of goodly appearance, pleasing in manner and of sober habits, and was much respected by all those who knew him. Such was the esteem in which he was held, that Mr Jardine offered a reward of £100 for the apprehension of the person or persons responsible for the shooting.

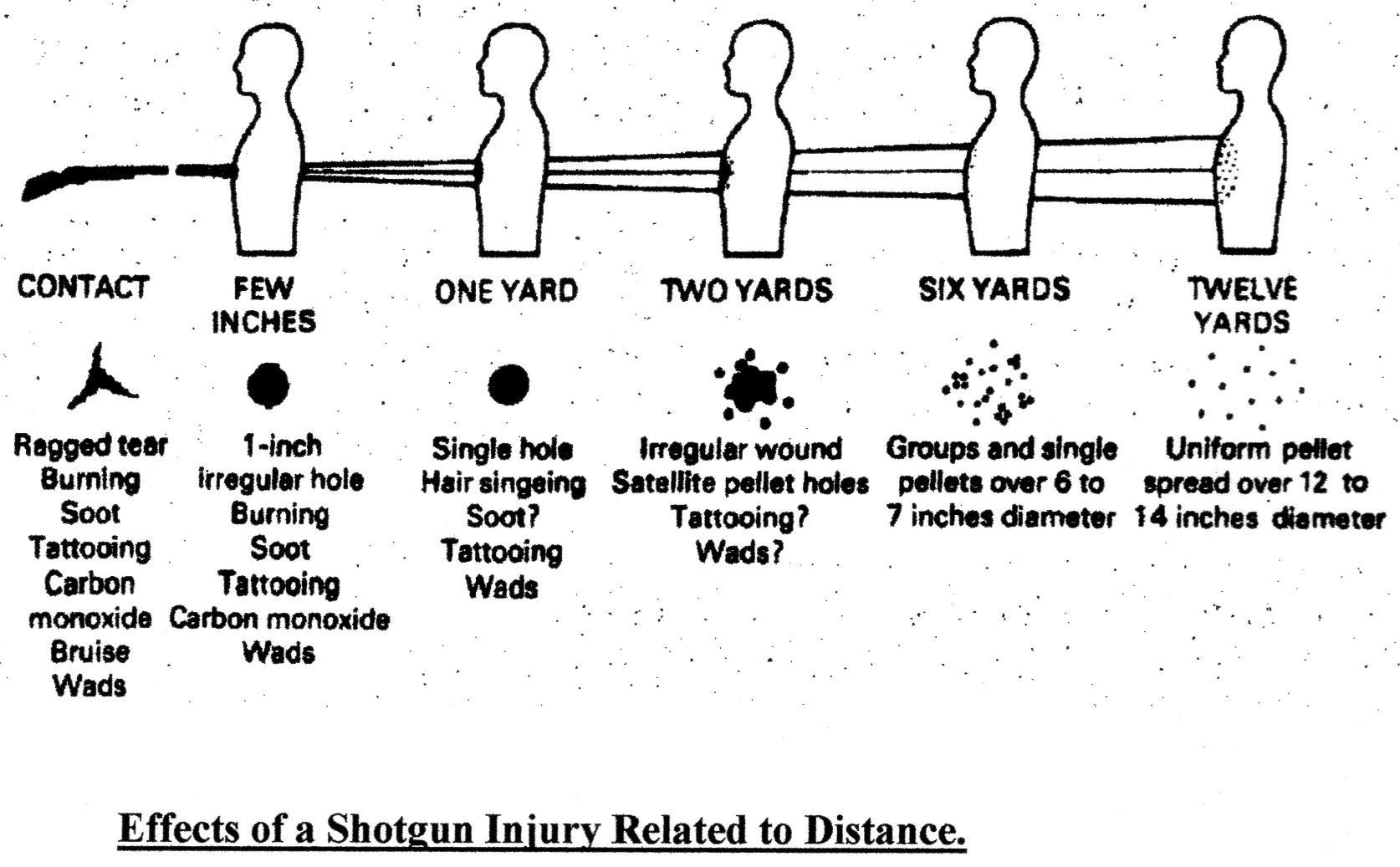

It later emerged from the extent of the injuries suffered, that Henderson had been shot at very close range, indicating a deliberate act rather than what was at first suspected, a shooting accident. From the state of certain items of the victim's clothing, robbery would appear to have been a likely motive. The moors around the area were well known for game, and as such, they would attract not only those with legitimate business there, but also poachers who would certainly have found the weather conditions on that day a distinct advantage for their clandestine work. Soon after the incident had been reported, a group of men who at the time had been observed on the moors with guns, were arrested on suspicion of being responsible for the shooting of Henderson. However, further enquiries revealed that they were, in fact, an organised shooting party from Smithills Hall and guests of the local landowner and magistrate, Peter Ainsworth.

Attention was focussed on a local collier, James Whittle, who lived with his parents in one of the cottages at “Five Houses" on the Winter Hill road. He was reported to have been seen on the moors that day with a gun. As a result, he was duly arrested on suspicion of the shooting and taken into custody. The Inquest into the death of Henderson was held on Tuesday 13th November 1838, at the Moorgate Inn, Horwich ( now the Blundell Arms), and adjourned until Friday 16th November. After witnesses had given their evidence and further enquiries completed, a verdict of 'Wilful Murder' was returned against James Whittle, and he was committed to Kirkdale Prison, Liverpool, to stand trial at the Lancashire Lent Assizes at Liverpool in 1839.

PRESS REPORTS OF THE INCIDENT.

“HORRIBLE MURDER AT BELMONT."

“ Yesterday about one of the clock, one of the most dreadful and atrocious murders was committed in our neighbourhood which has now fallen our lot to report. It was with no common feeling of regret that we now take down to make public the gross act of great turpitude. Up to this time, the deed is wrapped in mystery. By the kindness of two medical gentlemen we have heard the particulars of the event and we are grieved to be compelled to make this public. All who know this country known that there are parts which are secluded and wild. Imagination pictures deeds of violence as we pass such tracks, and it was on one of these bare and barren spots that the murder was perpetrated. A poor itinerant Scotsman is the victim. With another of his countrymen, he was in the habit of travelling the county. The deceased was going by appointment to meet a friend at Five Houses near Two Lads, crossing from Horwich to Belmont. The non-appearance of the deceased induced the other Scotsman to go in search of him. The unhappy man discovered him by the roadside in a dying state, a shot having passed through his head, found its vent through the left eye. The face was terribly blackened. When found, he uttered, “I'm robbed, I'm killed".

“ His friend having to meet him, went back to the Black Dog at Belmont, where they ought to have dined, the dinner was ordered, but finding he did not come, he went in search of him. He states that while on his road, he met a tall man in shooting coat with a gun. He states that the stranger immediately lowered his gun and he saw him no more. He sought his friend and never heard of him until he heard of his death. No suspicion being attached to the man who gave evidence, he was allowed to go on his way and wept as he went to Blackburn. The body of the man presented a fearful spectacle. Mr Wright of Belmont was active in ascertaining as far as possible, the circumstances of the case immediately it was known. We are anxious as far as possible to give publicity to the murder that the circumstances being known, someone may perhaps be able to throw some light on the matter. The part of the country described is well-known. It was daylight when the murder was committed. The victim is dead and may be, we hope, identified, and we feel that no better way of getting information regarding this barbarous act, can be obtained than through the press, and hope the inhabitants of Blackburn will assist in the discovery and apprehending of the person who knew, and is likely to give some information regarding the individual in question."Bolton Chronicle, Saturday November 10, 1838.

HORRID MURDER AT HORWICH MOOR NEAR BOLTON.

“We have of late observed with feelings of the utmost horror, the frequent recital in the public journals of the perpetration of barbarous and inhuman murders in the Sister Isle, but little did we think that we should be called upon to relate one of those dreadful instances of desperate depravity which reflects disgrace not merely on the age in which we live, but on human nature as occurring within the confines of our own country. It is our painful duty to give the particulars of a most horrid assassination which took place on Friday last at noon day on Horwich Moor about two miles from Belmont. On diverting from the Bolton Road to Belmont by the print works of Messrs Spencer and Winder, the traveller from Blackburn proceeds about half a mile up the New Preston Road to a gate 220 yards distant from the Wright's Arms.On going through the gate he proceeds along the base of a long chain of hills on his left, having a fine view to the right of Hill Top, the mansion of Thomas Wright Esq, and on the left a modern ruin called the Sheep Folds. On arriving at the top of Winter Hill, elevation 1,500 feet above sea level, we enter Horwich Moor the scene of the dreadful event. About half a mile from the nearest house by the side of the road, the victim of this deadly attack was shot in open day and thrown into the ditch. The bed of the ditch was covered with a small quantity of water. The deceased who was a traveller in the employ of Mr. John Jardine in this town, had travelled from Blackrod early in the morning and was proceeding on his road homewards through the moor when his further progress was arrested by the deadly hand of the assassin."

Blackburn Standard, Wednesday, November 14, 1838.

The Blundell Arms, Horwich ( formerly the

Moorgate Inn).

Drainage Ditch along Winter Hill Road towards Horwich.

“Yesterday an Inquest was held before William Smalley Rutter, Gentleman, Coroner, at the Moorgate Inn, in the parish of Horwich, on the body of George Henderson who was found on Friday morning last, lying in a ditch in a wounded state. The Jury assembled precisely at eleven o'clock having viewed the body of the deceased previously which had laid at a beer-shop at Five Houses about two miles distant. The following were sworn onto the Jury:

Mr. Richard France , Foreman.Mr. Titus Barlow.Mr. John Pendlebury.Mr. William Longworth.Mr. John Hopwood.Mr. Thomas Markland.Mr. Hugh Grundy.Mr. Richard Crankshaw.Mr. Robert Barlow.Mr. John Knowles.Mr. Richard Booth.Mr. Robert Orrell.Mr. Joseph Winter.Mr. James Spencer.Mr. William Longworth.“Thomas Whowell stated that he resided at Holden's Farm on Smithills Moor with his grandfather Thomas Walsh. On the Friday morning he was going with his brother's dinner to the coal-pit on Winter Hill. He saw a Scotsman pass by carrying a bundle at the end of his stick. He passed him about 100 yards. As he was going straight along the road from Five Houses to the Winter Hill Tunnel, he heard a moan and looking up the road, he discovered several spots of blood. He was terrified and set off running immediately to the Tunnel to get some help. James Fletcher who was getting his dinner, came back with him to the spot where he heard the moaning. On going to the ditch he observed the Scotsman who he had seen passing that morning lying on his back in the water. There was blood then flowing from his head. Fletcher and he could not lift him and so he sent for further assistance. The blood in the road was about three yards from where the victim lay. There were no marks as if the body had been drawn across the road. From the place to the Tunnel was about 400 yards. The bundle and the stick were lying at the edge of his feet, He spoke only once when he and Fletcher got to him. He said," Oh Jamie, Jamie, they have robbed me". From the time he heard the moaning to the time he got to the coal pit he saw no other person about the moor. It was terribly misty. He could see no more than a yard or so before him. Fletcher was the very first man who saw him after he got to the coal pit. He did not hear a gun going off. When he saw the Scotsman pass, he was perfectly sober. The breeches pockets of the deceased were turned out. There was not sufficient water in the ditch to cover the body. He could not tell who he meant when he said ,"Jamie". He heard no report of a gun on the moor at this time. When he got to the Tunnel, he found Fletcher's daughter there. There was no one else. The daughter had brought her father's dinner from Horwich."“James Fletcher stated that he lived at Horwich and was a banksman. The pit where the boy came from was the pit at which he was employed. It was distant from the Tunnel 400 to 500 yards. On Friday last he was opening a delph at the side of Winter Hill gate, a short distance from the Tunnel. His daughter had brought his dinner to the pit and, as it was rather wet, they went to the Tunnel. On going towards the 'Stumps,' he heard the noise of a gun being fired. He said to his daughter that it was rather rare game for the poachers that day, for the keepers couldn't see them. From the delph to the Tunnel was about 160 yards, and from the Tunnel to the pit was about the same distance. When the boy came to the Tunnel he had been there about ten minutes. The boy came running to the Cabin door. He said he had seen some blood and thought a man had been killed for he heard a moaning noise. He went back with him and discovered the deceased lying in a gutter by the side of the road. The body was in some water. He could not lift him out so he sent his daughter to Garbutt's for assistance. He lifted the victim on the side of the bank and he gave a deep sigh. He observed that he had a parcel to send off on Monday and then he said, “Damn them", after which he put his hand to his nose and in an attempt to blow it, the blood rushed out of the socket of the left eye, the other eye had obtruded itself from the socket more than two or three inches.

He had been shot and the mass of the shot had passed just under the right ear. Thomas Ratcliffe came and assisted him to get the deceased out of the ditch. When they got him out, they found the waistband of the breeches undone, except one button, and the right-hand breeches pocket was turned out. He laid the body on the ground and rested the head on his knee until a chair was brought. They then carried him down to his master's, where the body now lies. He remained with him until he died which was about half-past two the same afternoon. The brains came through the eye which was blown out. The cheek and under the ear was stained with powder marks, and the roots of the ear or eye were projecting out. The wound at the ear seemed as if it had been made by the muzzle of a gun put against it. The brains were lying scattered about the road. There was no damage done to any other part of his dress. After he heard the report of the gun he saw no person about. There had been a tramp in the Cabin in the morning. The report of the gun was not distant, and it came from the direction in which the boy ran from. It was the report of a gun, not a pistol, such a fire as might come from a sportsman. He had never seen anyone with a gun that morning, and that was the only report he had heard that day. It was not such a day as a sportsman would select for shooting because it was so misty."

“James Ratcliffe stated that he lived at Horwich and was one of Mr Garbutt's banksmen. The first that he heard of this was from Fletcher's daughter who came running down the road to the coal pit. She told him that her father had sent her for him to help get a man out of the ditch. He went and assisted him. His master and Whittle's father came up, and Mr Garbutt sent Whittle's father for the doctor and a constable. We then carried the deceased down to Five Houses, and he saw the wound on the Scotsman's ear which was blackened with powder. He did not hear the report of any gun. He was working at the pit about 600 or 700 yards from the spot where the deceased lay. When the boy Whowell came he was in the Cabin eating his dinner. He had not seen anyone with a gun that day. He had seen the first Scotsman passing an hour before in the direction of Belmont. He saw him afterwards that day, when he was sent for from Belmont by Mr Garbutt. He said to him on hearing the particulars of the murder, “It might have been me". The coal pit where he worked is near the road. He did not know the Scotsman."

“Mary Entwistle was the daughter of James Fletcher and was at the Tunnel with her father when the boy came in. She lived in Horwich and took her father's dinner to the stone pit on Friday. She went the road the Scotsman did. It was about 12.30p.m. when she arrived. She knew the boy Whowell but she had not seen him before he came to the Tunnel. She heard the gun fired but saw no other person about. After the boy came they went with him to where the deceased lay. She went to the pit to Ratcliffe for assistance and afterwards to Garbutt's for the same reason. Mr. Garbutt was at home and accompanied her and John Whittle (the prisoner's father) back to where the body was lying. She then went home. At about 8.30a.m. that morning she saw Whittle with a gun shooting near her house. She thought he had the same clothes on then as he had now. She was sure that it was him for she knew him well. She never saw anyone with a gun besides him that day. He was firing upon the moor at some moor game but he missed them. Her house is in the hollow near to Five Houses. She did not go into Garbutt's house to give the alarm but shouted out, and told him that a man was lying in a ditch. Both Mr Garbutt and his wife came out. Whittle's house is a door or two from Garbutt's and the prisoner lives with his father and mother there. She lives about 200 yards away in what they called Quaker John's House. She did not see the prisoner again until 5.00p.m when he was standing by Garbutt's."

“William Garbutt stated that he knew the deceased by sight, in consequence of his regularly passing his home, but he never frequented his home during his travels. About noon on Friday last, he came in for the last time. He was alone when he came in, and he called for a glass of ale and drank it off twice. When he came in, the two carters were already in the house. This was about 20 minutes before the girl came in to give the alarm. He had seen Whittle before that day in the forenoon. At daylight he heard someone firing on the moor. The prisoner's father was that morning getting in some potatoes for him. He said, 'there is a great deal of shooting going on this morning'. He replied,' yes, I have seen some smoke twice'. While talking to his father, he saw some person which he believed was the prisoner, come through the hedge bottom with a gun in his hand, just before he had heard three reports of a gun. This was about 9 or 10a.m. He was never seen at his home after the dead body was brought in, but his wife told him that she had seen the prisoner look into the window on the Friday morning whilst the deceased Scotsman was still inside. “ Robert Makin, Constable of Halliwell stated that he informed the prisoner of the charge on which he was being arrested. He had asked, 'Have you seen the Scotsman?' Whittle had replied 'Yes, I have seen him and spoken to him'. The constable then asked him how he knew it was the man. He replied,' From the description that had been given afterwards'. He then asked him what kind person he was and what dress he wore. The prisoner replied that he could not tell. He afterwards said in the lockup, on being asked by the constable what had killed the deceased, that it was not a bullet but slugs. He then stated that he had been on the moors that morning but with no gun on him."

“An adjourned Inquest was held on Friday 16th November 1838. Thomas Rutterworth, residing at Blackrod, stated that he knew the deceased. He was in the same way of business as the deceased. He was in business on his own account and had seen Henderson on the Thursday night and had stayed with him at the Cock Inn at Blackrod. He saw him start on his road homeward at 8.00a.m. He had no opportunity of knowing what money he had about him. He heard him call for some port wine at the Inn which he paid for in silver. The Coroner addressed the prisoner, “Whittle, the evidence is now closed. Now is the time for you to say anything in your defence or to call any witness to prove where you were at the time when this horrid transaction took place". Whittle protested his innocence and said that he hadn't anything further to say than that he was at home at the time when the alarm was given, and also at Five Houses at 12.00 noon, adding that his father could prove this. A proclamation for witnesses for the defence was announced, but not a single person offered to come forward. The prisoner was about 22 years of age, six feet tall, possessing a dark, morose, unpleasant countenance, but strong and athletic form. He has of late been a lawless, dissolute and reckless character, known for poaching. His habits of indolence had been latterly more confirmed, having formed an illicit connection with a young woman in the area to whom it is said, he was to have been married in the week previous to the murder."

Blackburn Standard, Saturday 17 November, 1838.

“Several witnesses were examined who proved the prisoner was at Five Houses on the day in question at 12.00 noon, and that at the time the deceased passed Five Houses, the prisoner was seen to leave his father's house and go in the direction of where the deceased's body was found afterwards. The prisoner was committed to Kirkdale for trial at the Liverpool Assizes."

The Manchester Times, Saturday 17 November, 1838.

“George Henderson was shot through the head by some villain and his pockets rifled after which the body was thrown into a ditch by the road side. He ( the accused) had a single barrelled gun which was a percussion piece. The Coroner asked the prisoner if he had any witnesses to prove where he was at the time of the murder. The prisoner's father John Whittle appeared very much agitated and stated that his son was at home when the murder was committed."

Wheeler's Manchester Chronicle, Saturday 17 November, 1838.

“About 10.00 a.m. in the morning, Mr Benjamin Burrell, the friend referred to, arrived at Five Houses and went into the beer-shop kept by Mr. W. Garbutt, where he waited for half an hour. We have to add that Roger Horrocks, who was found in a turf-cess with a gun at his side, was at one time supposed to be the guilty party, but closer evidence fixed upon a man names James Whittle, the former was liberated and the latter arrested. On Tuesday, November 13th, the Inquest was held and in consequence of the reports that were current on Friday and Saturday, Thomas Wright Esquire and Peter Ainsworth had thought it right to direct the arrest of a collier named James Whittle who was in the employ of the latter. William Garbutt, beer-seller and master collier, said he lived at Five Houses, Horwich. There are no other houses on the road but those between Horwich and Belmont. A girl informed him in the forenoon of that day. He recollected seeing him fire a gun at the bottom of his garden on Friday morning. He saw Whittle pass by his house while the Scotsman was inside. There was no other company. Many people came in to see the body but he did not see Whittle amongst them. Burrell, the surviving Scotsman, said he was going to Belmont and saw a man near the place where Henderson was found, above the hill, and he had a gun. A verdict of Wilful Murder was returned against Whittle. The trial took place at Liverpool Crown Court on Tuesday, April 2nd, 1839."

Horwich, its History, Legends and Church, Thomas Hampson, 1883.

“Adjourned Inquest – Yesterday morning at 10.00 a.m. the adjourned Inquest was held. Daniel Cook, Constable of Sharples, was called in. He said that he had been sent for by Mr Wright to apprehend at the coal-pit, Whittle who worked there. The Constable of Halliwell took him into custody. The prisoner said he had no gun with him on Friday afternoon, and that he was out with Mr. Matthew Lambert. He said that he had shot a bird that day but couldn't remember what kind. Henderson had made an appointment with another Scotsman, Benjamin Burrell, to meet on the road over the moor and dine at Belmont. Burrell arrived at Five Houses about 10.00 a.m. and he waited at Mr. Garbutt's beer-house. He waited about one and a half hours, and then left a message that he would meet Henderson at dinner in Belmont. At approximately 12. noon, the deceased arrived at Garbutt's and was told that Burrell had gone on, so he hastened on. At about 12.15p.m. the body was found, and there was a coal-pit about 300 yards from the spot. One of the banksmen took Henderson by the hand and said, “I think you are hurt, sir". The deceased replied, “I am robbed, Jamie, and I should have sent a parcel off on Monday". He was immediately removed to Garbutt's who, on hearing the news, got all the workpeople out of the pits, and the moors were scoured in all directions. From various circumstances which came to light, it was deemed necessary to apprehend James Whittle, a young man of 22, who resides next door to Garbutt's and is employed as a collier at Mr. Ainsworth's pit in Halliwell. “

“ Garbutt immediately sent men on horseback to Belmont for Mr. Burrell. On his return, he stated that when he arrived near the spot, a tall white looking young man dressed in blue clothes with a gun in his hand asked him, “ Is there any game about here?" Burrell replied, “ I believe there is “. Whittle then said, “If you go with me a bit, you shall have the first that I kill". Burrell declined the offer saying that he had business to attend to. After walking a few yards, he turned to see the man with the gun levelled as if to shoot him. He pretended to have been aiming at birds. Burrell proceeded but kept an eye on the man as he went. When this was related, suspicion fell immediately on Whittle who was exactly the sort of person described in both dress and appearance. Whittle was also seen opposite Mr. Garbutt's house without a gun at the time the alarm was given. He made off without redering any assistance, and did not return until night. He also led a dissolute life of late. Mr Jardine, the deceased's employer, had met Henderson on Tuesday night at Preston, and received all the money he had collected upon his journey. Mr Jardine conjectures that he could not have had more than £15 about him at the time of the murder. According to a witness, Thomas Whowell, Henderson passed him about 12.30p.m. carrying a bundle on the end of a stick. He heard moaning about half a mile from the pit, and a further 10 yards, he saw blood on the road."

“George Wolstenholme, Surgeon of Little Bolton, examined the head of the deceased. There was a wound in the right temple, and the frontal bone was fractured from one temple to the other. The left eye was carried away completely. He took off the front part of the skull and ascertained that the posterior part of the eyeball was carried away, as well as the bone which forms the roof of the orbit, and which supports the anterior lobes of the brain. Most of that portion of bone was carried away. He found in the brain, six pieces of lead which are either shot or slugs. He believed that the principal part of the shot escaped through the left eye. Every part of the brain was perfectly healthy except part of the anterior lobes which were lacerated. This injury had caused death. He thought that the person who shot must have had a gun or pistol very near, as the shot was not scattered, and the wound was about one inch in diameter."

The Manchester Courier, Saturday November 17, 1838.

“About 12.00 noon on Wednesday 14th November, the funeral procession started from Five Houses at which time there were not about a dozen spectators. The coffin which contained the body, was of good substantial oak, the inscription on the plate merely denoting the name and age of the deceased. The corpse was placed in the hearse by six of Mr Wright's servants who were in attendance at Five Houses by his direction. Also attended Whittle's father who witnessed the spectacle with emotions of deepest sorrow. The hearse was followed by a carriage containing the employer and three other friends of the deceased.Mr. W. Jardine, Mr .J. Jardine, Mr. P. Johnson and Mr. G. Brown rode in the procession. The cavalcade passed the spot where the murder was perpetrated and continued to course over Winter Hill to the New Preston Road whence diverging to the left, it proceeded to Belmont and then fell into Bolton Road. It reached the village of Over Darwen about 3.30p.m. The streets were lined with spectators from the Bowling Green Inn at Livesey Fold. On arriving at the Crown Inn at Nova Scotia, the cortege was met by Rev. Francis Skinner, Minister to the Scottish Church, and twenty-five of his countrymen attended. The procession moved towards Blackburn, and passed through Darwen Street, Church Street and Salford Street, reaching the Presbyterian Church in Mount Street at 5.00p.m. The chapel was crowded to excess with not less than 1,000 present. The following Sunday afternoon, the Rev. Skinner in his funeral discourse, used the text, “ In the day of adversity, consider."Bolton Chronicle, Saturday 24 November, 1838.

CHAPTER TWO.

THE TRIAL.

R v WHITTLE.

Lancashire Lent Assizes – Liverpool Crown Court.

Tuesday 2nd April, 1829.

Before

Lord Justice Baron Parke.

James Whittle aged 22 was arraigned on a Charge of having wilfully murdered one George Henderson on Friday 9th November, 1838 on Horwich Moor by the discharging at him of a loaded gun.

PLEADED NOT GUILTY.

Counsel for the Prosecution:

Messrs Dundas, Peel and Cross.

Instructing Attorney: Mr. Holden of Bolton.

Counsel for the Defence:

Mr. Sergeant Wilkins.

Instructing Attorney: Mr. Taylor of Bolton.

WITNESS STATEMENTS.

Jonathan Hardman.Jonathan Hardman, a surveyor from Bolton, produced a plan of the area of the killing, which showed Five Houses as a group of cottages on Winter Hill. They were known locally as 'Garbutt's' after the owner William Garbutt, whose cottage was used as a beer-house for the use of miners, packmen and travellers. He indicated that the distance from Garbutt's to the spot where Henderson's body was discovered was 972 yards. Nearby was the entrance to one of the coal mines called the Tunnel. The distance from the spot to the Stumps which was a boundary wall five feet in height, was 212 yards. The distance from the Stumps to the Tunnel was 137 yards. The Moorgate Inn at Horwich was approximately 2 miles distance from Garbutt's. There was no footpath between Horwich Moorgate and Five Houses, so people crossed over the moor. On the moor were numerous ditches cut for drainage. Lying between the spot where Henderson's body was found, and the Winter Hill road was a deep ditch approximately 3 feet wide, which was extended on the right side of the road from Five Houses to the Stumps.Thomas Whowell.Thomas Whowell, a boy of 14, worked for Thomas Walsh of Horwich, and was riding on the morning of the 9th November near to Adam Hill which was about half a mile from Garbutt's. He was on his way to see his brother who worked in one of the mines on Winter Hill. Whilst he was on Adam Hill, he heard the midday bell ring from Ridgeway's Works in Horwich. When he arrived at Garbutt's, he saw the Scotsman come out and go up the road. Thomas's horse was making heavy going up the hill so he swore at it. When he came to the pit he stopped to take his brother's dinner. The Scotsman was walking with a stick and bundle on his back, and came up to him and reproved him for swearing. It was custom to call any packman Scotsman, because many travelling packmen originated from Scotland. The pit was approximately 400 yards from Garbutt's.He stopped with his brother for about ten minutes and then began his journey down the road. After going about 300 yards from the pit, he heard a moaning noise coming from the ditch on the side of the road. A bit further on, he noticed blood on the ground. He was afraid and did not look into the ditch but went forward to the Tunnel where he saw James Fletcher together with his daughter Mary Entwistle. He told them what he had heard and they went with him to the place where they found the Scotsman lying in the ditch. It was the same man he had seen going up the road. Fletcher tried to lift him but he could not. Thomas went for assistance and met Garbutt and John Whittle ( the prisoner's father) coming up the road. He had known the prisoner for about two years, and he was in the habit of shooting. The day was very misty and he could not see far before him. He heard the moaning about 12.30 to 12.45p.m. The deceased appeared to be in great agony and struggled much with his hands. He did not notice any footmarks near the place where he lay. He did not see a gun or a pistol near the spot, or see the body when he passed it first time. The bundle was lying beside the deceased in the ditch, and did not appear to have been opened. He did not observe that the pockets were turned out.

James Fletcher

James Fletcher, a banksman at the coal pit near to Five Houses, stated that on the 9th November, he was working in a stone delph on Horwich Moor near the Tunnel. About 12.30p.m. his daughter came with his dinner and he went with her to the Cabin to eat it. This was used by used by quarry worker and miners to eat their food. When near to the Stumps, he heard the report of a gun from the right of Five Houses. Whilst getting his dinner in the Cabin, Thomas Whowell came in, and in consequence of what he had stated, he went with him to the place where the body lay. Whowell pointed out the spot and when he went back to it, he discovered the deceased lying on his back. One of the eyes was entirely blown out.

When Thomas Ratcliffe another banksman came up, they lifted the body out of the ditch. When they looked, they saw that the right-hand pocket hung over the trousers on the outside, and they were torn down from the pocket. He did not observe that the left pocket was turned out in the same way. They carried the deceased to Mr. Garbutt's as soon as possible, where he died about 2.30p.m. His right ear was much discoloured and black with powder. They were assisted by William Garbutt, James Heaton, James Bamford and a man named Lomax. He was placed on a table, the body being washed and the eye replaced in its socket. He did not see any firearms near the site, but many blood stains on the ground close to it. In the left waistcoat pocket, Fletcher and his friends found one shilling and eleven pence. In Fletcher's opinion, the trousers appeared to have been unbuttoned by force. When asked if it would have been possible for a person firing the fatal shot to have reached the Cabin without being seen on the road, Fletcher said it was impossible. The person firing the shot would have to cross the moor and get to the Cabin without Fletcher seeing him. Fletcher had about 130 yards to go after hearing the shot, whereas the man would have to go about 300 yards. On his return to the Cabin, there was a man about fifty years of age asleep there. He was a stranger to the neighbourhood, and he thought that he was a 'navvy'. He had a stick and a bundle attached to it. He was dressed in fustian trousers and had a blue waistcoat, and on awakening he left the Cabin.

Thomas Ratcliffe.Thomas Ratcliffe had been working in the coal pit next to Five Houses. Mary Entwistle had come to him and after hearing the story, he went to the site where the victim lay. The ditch was about half a yard deep and of a similar width. He heard the gun fired below Five Houses on the other side of the pit about 10.00a.m. in the morning. He had not heard a shot about 12.00 noon because the wind was blowing towards the Stumps. He had never known Whittle to do any harm to anyone, and described him as good-tempered and well-behaved.Site of the Winter Hill Tunnel.

William Stott.

William Stott was aged 13 years and was examined by Mr. James Cross, partner in the firm of Cross and Kay, Attorneys, Bolton. He worked in the Tunnel where he had been on the day in question. He had seen Whittle inside the Cabin at about 11.00a.m. in the morning. When he had seen Whittle, he had asked him the time and had been told 11.00a.m. Whittle had been dressed in the clothes he was now wearing. With Whittle in the Cabin had been William Simms and an old tramp, but he could not remember how Simms was dressed. Asked why, he replied that Whittle had been closer to him and it was dark in the Cabin. He went to the Tunnel and was there about ten minutes, and when he next looked in the Cabin, Simms had gone but Whittle was still inside with the tramp. He then made a rather strange statement saying that he had been approached privately, and told to keep to the same story. He had also been informed that there was a £100 reward to be had, and had been instructed to say what colour Whittle's clothes were. On reflection, he was sure Simm's jacket had been dark, and he had gone into the Cabin to shelter from the rain.

William Fletcher.William Fletcher was the son of James Fletcher and had been working at Garbutt's on the day in question, in place of James Heaton. He left work about 11.00a.m. and on his way home he had seen Whittle in an old road near to a 'turf-cess' which was between the pit and Garbutt's house. He had a gun in his hand. Whittle asked if he had a 'play-day', a day off, and he replied he had from that time for the rest of the day. They then walked together until they were about three fields away from his home. It was about 11.45am. when he arrived home. Whittle had left him between Five Houses and the pit.

Sarah Lomax.

Sarah Lomax lived at Five Houses between Whittle's and Garbutt's, and she was at home when the killing took place. Before she had heard the news of the killing, she had seen Whittle coming from the direction of the spot where the body was found. This would be about 12.00 noon. Whittle was standing in the cart road near the house.

Anne Garbutt.

Anne Garbutt lived next door to Sarah Lomax and was also at home on the 9th November. From her window she had seen Whittle go past about 12.00 noon and Henderson was still in her house. Immediately Whittle passed, Henderson went out. Twenty minutes later, she saw Whittle again through her window, this time he was coming from the direction of Horwich a little before the murder. The first time he was going towards Belmont and the second time he was coming from his own door and was not wearing a hat. She definitely saw Whittle pass her window around 12.10p.m. A stranger on a grey pony called at about 2.30p.m.

William Heaton.William Heaton was a carrier for Garbutt and between 10.00 and 11.00a.m. on the 9th November, he was going up Winter Hill from the Belmont side with a horse and cart. At the bottom of the hill he met William Simms going in the direction of Belmont.. Late he met Burrell going in the same direction. He stopped to load his cart at the delph where James Fletcher was working. He then went on to Garbutt's reaching it about 12.00 noon, where he found Bamford inside. He had been in about twenty minutes when Whittle came in and asked about a horse being ill. Two or three minutes later, Mary Entwistle came down the road shouting, and by then, Whittle was on his way out.Benjamin Burrell.

Benjamin Burrell stated that in the month of November, he was living in Blackburn, and was in the service of a Mr. John Foster as his traveller. He knew George Henderson who, last November was also in the service of Mr. John Jardine of Blackburn. He was about twenty years of age and was a fellow Scotsman. It was their practice to go certain routes to sell goods, take orders and collect money, and this was one of the duties of the deceased. Both their rounds took them over Horwich Moor to Belmont. They went across the moor every other Friday, and the 9th November was one such day. When they got home in Blackburn, they accounted for the fortnight's proceeds. He knew Garbutt's beer-house and on the 9th November they appointed to meet there a little after 11.00a.m. He went to Garbutt's according to his arrangement and reached there about 10.00a.m He remained there till about 11.00a.m.and since Henderson had not arrived, he left word that he had gone on to Belmont. When he left Garbutt's house, he went in the direction of a place called the 'Stumps', and he had seen the place where the body was found, and had passed it alone on the 9th November. As he was going up the hill, one of the colliers called to him, 'Are you going up?'. Near to the place where the body was found, he saw a man about 50 yards off, and he had a gun in his hand.

He came towards him as he went on and came off the moor onto the road behind him. There is a ditch between the road and the moor. When in the road, the man would be about 10 to 12 yards away. He asked him if he had seen two men as he expected two to come off the moor. He was told that none had been seen. When he spoke, Burrell was near enough to see that he was a tall man dressed in dark clothes. The gun he had with him was a single-barrelled one. Burrell walked up the hill and the man walked behind him. After proceeding a few yards, he happened to look behind him and saw the man pointing the gun towards him about 10 yards off. When he turned round, the man asked him if he saw some birds but there were no birds in the direction in which the gun was pointed. The man came nearer and Burrell asked him if he could shoot birds flying. He said he could and that if he would go with him on the moor, he would give him or kill him a bird and show him a good path to Belmont. Burrell told him that he was going to Belmont because the man had enquired. After the conversations which took place as they were walking, he told Burell that the path was against the wall and through the 'Stumps' and turn to the right.

He went through the 'Stumps' and the man came close to him. He observed his clothes, his trousers were blue and very much worn about the knees, a patch was upon one of them and they were very short. He had a blue coat and a dark waistcoat. He wore his hat very much over the eyes. He had the opportunity of noticing his gun, which had a single barrel and a percussion cap. He couldn't swear that the man he saw was the prisoner, but he had the same general appearance, was wearing the same kind of clothes, and was about the same height. He heard Whittle speak at the Inquest, and the voice was very similar to that of the man on the moor. Not seeing the appearance of a footpath, Burrell told the man that he had business to attend to and turned back. He did not observe the man following him. He then went down the road to Belmont and met two carters with three carts and three horses. Their names were Heaton and Bamford. They were about 200 yards from the Belmont side of the Tunnel. He reached Belmont just before noon, and was sent for to Garbutt's, and reached there about 2.00p.m. He saw the deceased there who died about two minutes later.

Joseph Halliwell.Joseph Halliwell, when examined by Mr. Dundas, stated that he was a corn-dealer carrying on a business in Skipton. In November last, he was in the service of Mr. Gerrard, another cattle-dealer from Bolton. On the 9th November, he had directions to call for a heifer at Walsh's Farm. He called at the place where he worked and by his directions went to the farm on Smithills Moor called Gilligant's. He saw Mrs Hood there and arrived at the farm at 12.25p.m. by her clock. He was not able to get the heifer and remained at the farm for no more than ten minutes. It was very foggy at the time. He was on his way to Belmont, and asked Mrs Hood to direct him. She told him that the road went to a place known as Holden's Farm. The road by which he went led towards a brow, and turning off to the right, this brought him onto Smithills Moor. When he got some distance he heard the report of a gun. By then, he had lost his directions and insisted that he was sober and had only three glasses of ale on that day. He went in the direction of the sound of the shooting thinking some gentleman might be shooting and would tell him the road to Belmont. He met the prisoner within a quarter of an hour. When he first saw him, he was about 30 yards off and it was very foggy indeed. The prisoner was running towards him and had a gun in his right hand. He got within a few yards of him when he spoke to him and asked directions, but got no answer. He was dressed in a blue surcoat, blue trousers and a blue waistcoat with a yellow spot.He thought it was the same waistcoat he had on now. He was running in the direction away from the sound which he had heard. After going about 320 yards from the spot where he met the prisoner, he came to a road. There was a ditch between him and the road. He saw a man lying in the ditch, the righ hand pocket of his trousers was torn down. He got off his horse to look at him and saw blood on his cheek which turned him very sick. He attempted to get off the moor and onto the road. He was riding a grey pony but could not get it over the ditch. He tried two or three times in different places and went down the ditch 40 or 40 yards. He then remounted and then tried to go back again, but he could not tell in which direction he was going. When the mist cleared away, he found himself close to Holden's Farm where he had originally started off. He knew Garbutt's and got there between 2 and 3p.m. and had a glass of ale on his horse. He did not know at the time, that the body of the deceased was lying in the beer-house. He said nothing about the body in the ditch as he did not know anybody in that part and was apprehensive. He had on him £304.16s. 6d. of his own money. In going along the road to Garbutt's, he saw a man and his wife about twenty yards from the place where the body was found.

Cross-Examination of Halliwell by Mr. Wilkins ( Defence Counsel). Halliwell had stated that he had been a cattle-dealer ever since last Christmas, buying and selling for both himself and other people. He had bought off a man near Giggleswick in Yorkshire several times, but he did not know his name particularly. He had bought from him many times, probably about half a dozen. He couldn't say how many times he had bought from John Wilson, a butcher and cattle-dealer from Colne. He couldn't say how many times this was. He had bought calving cows off him since last Christmas but couldn't say how many, or how much he paid or how often. He had received £304 by his own labour and had brought from home that day. He lived with his mother and was a drover. She was a widow and lived in a cottage and subsisted on what he gave her. His father had also been a drover but left no property. When he first started out as a drover, he earned a shilling a day and his expenses. He was then only 14 years of age. He had from Mr. Gerrard 24 shillings a week when he was in his service, amounting to £62. 10s a year, and he had calculated this amount before coming to court, knowing that he might be asked such a question. The money was left at his mother's cottage in Yorkshire until the Monday week before he started. She gave it to him at that time, and he had shown it to no one else and it was in notes. The rent of her small cottage was £3 a year.

He did not know at what time he got up that morning. He swapped a cow with a Mr Webster of Footed Brook that very morning. He let him have a beast of his that he got from him a week before and another one. They had a glass of ale over their swop. They went back to Mr. Gerrard's, then to a beer-house and had only one glass of ale. He paid for one for another man there. They had a six-weeks reckoning and settled their accounts at Mr. Gerrard's. He paid him seven shillings and sixpence or fifteen shillings and sixpence, he couldn't say exactly which. He left Gerrard's at 10.00a.m. and the horse he rode was Mr. Gerrard's. The first place he stopped at after passing St. George's Church in Little Bolton was Mr. Ainsworth's pits. Whilst he stooped at the first pit he did not see John Entwistle eating his dinner. He saw another man at the first pit but he did not get off his horse. He would swear that he did not ask the way to the Green's Arms. The man directed him to Ainsworth's pits and he met up with John Walsh there. He asked him to drive his heifer for him which his master had bought from Walsh's master. He did not ask the way to Gilligant's Farm. He asked him if he could cross two fields but he said he could not, although he went across them anyway. It was between 11.00 and 12.00 noon when he got to the pit. He met Walsh's wife within 20 yards of the pit with his dinner.

He did not know Richard Nuttall. He offered a man 1s.6d to help him with the heifer over the moor. He may have called him Dick. At this time he had not yet seen the dead man. When he got to Gilligant's, he saw a clock and asked who was the maker, and it was not 1.25p.m. by that clock. He was not drunk and did not fall off his horse. He did not remember losing his whip and he did not tell Grace Whowell that he was so drunk he could not drive the heifer. He did not know the country there at all, nor did he know Garbutt's House or Quaker John's. It was a little after 2.00p.m. when he arrived at Five Houses and it was about two hours since he had last seen the body. He could not swear to the dress of the wounded man. His pack was laid upon the opposite side of the road in the ditch. He did not jump over the ditch himself. He asked his road to the Wright's Arms and he did not know whether he had told anyone what he had seen. He got to Proctor's at half-past three. John Proctor was landlord of the Duckworth Arms at Over Darwen on the main turnpike road between Bolton and Blackburn. He told him that he believed it was a Scotsman shot that day. He supposed it was a Scotsman from his pack. He told Mr. Proctor that he had seen the body and a person running from that direction with a gun on Horwich Moor. An Irishman and his wife whom he overtook on the road, told him a man had been murdered. He was fetched from Yorkshire to give evidence a week afterwards.

He never heard of the £100 reward being offered. He left Gerrard's service the Monday after Christmas Day, and on his solemn oath would swear he never heard of the reward being offered. The Constables of Blackburn and Bolton together with others, told him to look at the prisoner in the lock-up. He told them he would not swear to him by candlelight. The day afterwards, he saw him at Horwich Moorgate Inn at the Inquest, and then swore to him. He described the prisoner to the constable the Thursday night after the murder before he had seen him in the lock-up. What he said was written down by Mr. Perris, Constable of Blackburn. He mentioned everything as he had given it this day. On the evening, he was fetched from Westhoughton by Thomas Ellis, a drover from Yorkshire to see him.Re-Examination by Mr. Dundas ( Counsel for the Prosecution)Mr. Proctor lives at Over Darwen and it was 3.30p.m. when he told him what he had seen. He showed him a piece of the man's skull which the Irishman, whom he met with his wife, gave him, and which he said he had picked up on the opposite side of the road to where the man was lying. He couldn't say whether he gave an account of it to the people whom he saw at the Wright's Arms at Belmont. He knew the man very well when he saw him at the Inquest, and had no doubt that he was the same he had met on the moor with a gun.William Garbutt.He stated that he kept a beer-house at Five Houses and knew Henderson quite well, and was at home on the Friday. The other Scotsman called every other Friday on business between Horwich and Blackburn, and often changed silver and sovereigns for notes. Henderson was not a regular caller at the beer-house. At the time Mary Entwistle came with the news, Whittle was standing close to his right side, but he had no gun with him, and this would be about 1.00p.m. He had seen Whittle that morning about 8.00a.m. with a gun. He had also seen a person of about his height and dress similarly fire a gun on three separate occasions. About 10.00am he again saw Whittle, and then finally about 1.00p.m. leaving his house. He did not see him again that day. Many people came to see the body, but he did not see Whittle amongst them. The early part of the morning had been clear but it became foggy about noon. It cleared in the afternoon, so that men could be seen on the moors at a considerable distance. These proved to be a shooting party. Burrell had exchanged some money when he called at the beer-house, but not Henderson.

Mrs. Lambert.She lived at the Moorgate Inn, Horwich, and stated that she had been at home on the 9th November, and had seen Whittle about 1.30p.m. She had spoken to him and asked about her husband's gun, one which had been lost sometime before. Whittle had told her that he knew nothing at all about it. He was still at the Moorgate at 3.00pm. A servant came in and said that there had been a man shot on the moor, a Scotsman. Whittle then remarked that many of them went that way on Friday on their way home. He then stated that two or three of them made appointments to meet there on Friday and go home together. He then said that he had brought back the gun he had borrowed, and would never have another one in his house while he lived. She said that Whittle had left the house about 4.00p.m. She also stated that she heard of Mr. Orrell, steward of Mr. Wright's estate had called at Whittle's house to complain to his father about Whittle poaching on the moor. Whittle stated that he had not shot fowl as he came through Brownlow's Close, which lay between Five Houses and the Moorgate Inn.

Mr. Matthew Lambert.

He was the landlord of the Horwich Moorgate Inn, and he agreed that he had lent the prisoner a single barrel fowling piece with a percussion cap, on Thursday 8th November. He made an appointment to meet him on the Friday in Brownlow's Close, about 1 ½ miles from the Moorgate. Whittle had stayed at the inn until about 4.00p.m. on the Friday. Before leaving the inn, Lambert asked Whittle about the shooting of the packman, was it accidental or was it a wilful act? Whittle had replied that he did not know any details about it, but if it had been done deliberately, whoever had fired the shot, deserved to suffer for it. He stated that he thought it was not quite 1.30p.m. when Whittle arrived at the Moorgate. The foreman of the Jury asked what size of shot was in the shot bag, and Lambert stated that it was No 2 shot, and had been taken away in the shot bag by John Whittle, the Chief Constable of Wigan. The gun which had not been loaded when it was brought back, was handed over to a Mr. Peter Heron, a gun expert. The charge in the gun was not withdrawn. The weapon had been handed over at the Coroner's request to Constable Burrows. On the Friday, Whittle came to the Moorgate and brought a pair of grouse still warm. He reared the gun against the wall of the brew-house and went inside. We both left at 4.00p.m. and went in search of a hare up to the north of Brownlow's Close. He walked back with Whittle for about 600-700 yards, and then came back home again. Before leaving, Whittle explained he had brought the gun back and everything belonging to it.

Mary Cross.

Stated that she was employed by Mr. Lambert at the Moorgate Inn, and had seen Whittle on the Friday between 10.00 and 10.30a.m. in the back yard. There is a meadow behind the inn and she saw Whittle come across with a gun in his hand. They had heard about the murder about 3.30p.m. and the prisoner had left the Moorgate at about 4.00p.m. When Whittle had arrived, he had some birds with him which were still warm and obviously recently shot. She was not quite sure whether it was near to 12.30 or 1.00p.m. when the prisoner arrived at the Moorgate, but somewhere about that time.

Mary Entwistle.

She was James Fletcher's daughter and accompanied her father from the Tunnel to the stone delph and heard the report of a gun which would be about 12.30p.m. She went for help to Garbutt's. She knew James Whittle and had seen him on the Friday morning about 8.30a.m. between Five Houses and Entwistle Lane. He had a gun with him and was wearing a long blue coat, blue trousers and a blue waistcoat. The time from hearing the gun report and Whowell coming to inform her father about the incident was about thirty minutes. She had not seen Whittle on her way and had not seen him fire that morning.

George Wolstenholme.

He was a surgeon practising in Higher Bridge Street, Little Bolton, and stated that he had performed a post-mortem examination on George Henderson on Monday 12th November. There was a gunshot wound on the right temple, a bullet or slug had passed through carrying away the right eye. In the brain, he had found six pieces of shot and in his opinion, the victim had died as a result of this injury. The lead shot weighed 18 drams and was No 3 shot. He had weighed the shot with others bought from Samuel Cartwright, Ironmonger of 154, Deansgate, Bolton. Those from Cartwright's weighed 23 drams. The weight of the shot would not be affected by passing through the bone, although in his opinion, passing through the frontal lobe would affect the shape.

William Simms.

He was a collier and was going over Horwich Moor and called at Five Houses, and as he was leaving the beer-house, he met a Scotsman coming in about 10.00a.m. Going up the road, he met James Whittle between the Stumps and the Tunnel. He was carrying a gun, and he stopped and talked to him for about two or three minutes. He then went on to the Tunnel and the Cabin. There was nobody in the Cabin when he arrived. After a minute or two, an old tramp entered followed by Whittle about ten minutes later. Whittle did not have a gun with him. He left Whittle and the tramp together in the Cabin. He had been on the moor going to see his sister who lived in Belmont. The previous day he had been at work in Aspull at Lord Balcarres's mines. He had been two or three days idle, and had spent his time with people about the pits. He had received 23 or 24 shillings the previous Saturday in wages. He had worked that week for Mr. Gray, Lord Balcarres's agent, but had been turned off for drinking. On that Friday, he had been to Mr. Orrel's factory at Belmont, and it was between 10.00 and 12.00 noon when he arrived there. He had dinner with his sister in Belmont and then went to shelter from the rain in the Cabin.

Daniel Cook.

He was Constable of Sharples, and stated that on the Saturday following the killing, he went to arrest the prisoner. Whittle was brought out to him by Mr. Steward, Manager of the colliery, and he told Whittle that he was their prisoner. Whittle asked why this was happening, but Cook did not reply but brought out his handcuffs, but Whittle said he would go without them. Mr. Peter Ainsworth who was a magistrate, accompanied Cook to make the arrest, and Whittle was cautioned and told that he had no need to make a statement, but if he did, it could be used in evidence. Whittle said that he had not had a gun in the house since Sunday last. The whole party then set off to go to the Horwich constable. Cook and the prisoner walked together to Horwich and Robert Makin, Constable of Halliwell walked behind them. Whilst walking, Whittle told Cook that he was innocent of this crime. Cook replied, “ Jem, hadn't thee a gun in thy hands all yesterday?" Whittle replied, “No, not until the afternoon when I was with Matthew Lambert, and I shot a blue-beak, and I told him that the fellow that shot the Scotsman ought to suffer".

Robert Makin.

He was Constable of Halliwell, and stated that Whittle had told him that he had seen the Scotsman, and had in fact spoken to him at Garbutt's stable door. Whittle had also told him that the dead man was not the first Scotsman who had gone up the road that day. There had been another and he had seen them both. Measurements were taken at the scene of the killing. The distance from Garbutt's house to the first coal pit at which James Fletcher worked was 420 yards, and the second pit was 55 yards from that. The distance from the furthest pit to where the body was found was 507 yards. The distance from where the body was found to the Cabin of the Tunnel was 309 yards. It was 220 yards from the stone delph to the Stumps through which the road went. The distance from the Stumps to the Tunnel was 137 yards, and it was 112 yards from the place where Fletcher heard the report of a gun.

James Corless.

He was gamekeeper employed by Mr. Peter Ainsworth of Smithills Hall. He had been out on Horwich Moor with a shooting party consisting of Messrs Wright, Crompton, Ryding, Ireland, Horrocks and Ince. They were not local men but shooting guests of Mr. Ainsworth. He heard a gun fired on Smithills Moor about ½ mile from where the body was found. About five minutes later from a different direction, he heard another shot. The first shot was heard about 11.55a.m. and the second about noon. He was sure of the time because he heard a factory bell ringing. The shots were not fired from his party because all the guns were close together the whole day because of the mist.

ADDRESS FOR THE DEFENCE – MR. WILKINS.

“Members of the Jury, had it been made clear in your minds that the unfortunate man had in fact been murdered? After a good deal of investigation, I see good grounds for doubting this. Generally speaking, vindictiveness or a desire for gain are the incentives for murder. Was there any proof of vindictiveness on the part of my client towards the victim? Was there in fact, anything to warrant such a surmise? Was there any proof of a desire for gain? When the man was found, no money had been taken from him. His pack had not been disturbed, his stick and umbrella left untouched. The weather was very foggy and it was such a time that poachers would carry out their operations. It seems possible and probable from the state of the deceased's dress that he had ventured to the roadside for some particular purpose, to answer a call of nature, and had been shot by some poacher ignorant to this day of the accident or knowing it, concealing that knowledge through fear of the consequences. Would this be a natural or forced surmise?

You have been asked to infer from the flesh near the wound, that the gun was near when the shot was fired, but anyone would know that discolouration would be produced around a wound by the blow of a gunshot from whatever distance the gun might have been fired. It was the custom of parties of Scotsmen in the neighbourhood to get their silver changed into notes at the beer-house. The victim Henderson called there and had paid for a glass of ale from his waistcoat pocket in which money was found after he had been discovered in the ditch. He did not ask for change, the presumption being that he had been unsuccessful in his collection on that day. There are reasonable doubts and they must be given to the accused. Suppose it was murder, then the question is who had committed the murder? The indictment points to the prisoner but what was the evidence? The testimony of Halliwell is utterly unworthy of belief and it is totally improbable that he had, by any honest means, become the owner of the property he stated he had in his possession on the day of the murder. This is borne out by his wholly unacceptable manner in which he has given his evidence, and as such, it should be regarded as defective. There is no continuity in the events he recalls, and there are gaps in his evidence which are unaccounted for. Elsewhere, there is not a point in the case which is not accounted for.

The prisoner was out shooting all day, but was this an uncommon circumstance? It was nothing more than usual or ordinary. From the coal-pit to Belmont there was not another single dwelling but one solitary Cabin. Knowing the area as he did and the habits of the Scotsmen, was not the circumstances that the man was killed so near his own home, rather an argument in favour of my client's innocence than guilt? It was given in evidence that he was a young man of mild temper with no blemishes on his character. This must also weigh well in his favour. I would ask you to consider whether or not there is sufficient evidence to support the view that there is proneness to fit and fashion facts to a particular set of circumstances? Looking at the testimony of Benjamin Burrell, it is quite clear that he had no apprehension when he turned round and saw the gun pointing at him, then the prisoner dropped it to his hip. He had no suspicion that he intended to fire at him. If indeed, he intended to murder him, he could have done so without having his back to him. Would not any person preparing to shoot at game, have dropped his gun to the rest on being spoken to? In fact, there is nothing more common than carrying a gun pointing, on shooting at moor game on a foggy day. I would ask you to consider if there was anything suspicious about the manner of the prisoner? He was without excitement when he came from his dinner and spoke to the carrier about the horse being ill. Mr. Garbutt had considered it rather extraordinary that he should have asked had he a horse ill. Why should this be so?

It was an ordinary circumstance because he had a horse ill very often. He had one ill that day and the prisoner was a near neighbour. He was in no agitation, no trouble, no apprehension, and yet he walked about with an instrument of death in his hand. You have heard the testimony that my client did say at Matthew Lambert's, that he would have no more to do with shooting, but that arose from the annoyance from which he had been subjected by complaints from his father. Consider, if you will, the very important fact that the shots found in the brain of the deceased, were of uniform weight, while those in the shot bags and those in the box taken from the loaded gun were of different sizes. Those found in the gun and bag did not tally with those from the brain of the deceased. Members of the Jury, it is dangerous to lay too much emphasis on statements made by a person when apprehended, especially in a sudden manner. I therefore respectfully suggest that when my client had been questioned by the constable in the presence of his employer and local magistrate Mr. Ainsworth, and Mr. Wright, both of them owners of parts of the moor, he did in fact suspect that they intended to arrest him for poaching, and therefore made false statements to avoid being charged with that offence."No witnesses being called for the Defence, Mr. Wilkins concluded his address to the Jury. The learned judge emphatically recapitulated all the leading points in the case, directing the Jury to give the prisoner the benefit of any doubts they might entertain. His Lordship dwelt particularly on the fact of all the shot found in the head of the deceased being of one size, whilst those which the prisoner had used proved to be of different sizes. The Jury retired at 9.00p.m. to consider the evidence and returned at 11.00p.m. with a verdict of NOT GUILTY. The Foreman of the Jury remarked that the decision had been arrived at in consequence of the defective evidence of Joseph Halliwell. James Whittle was immediately discharged.The trial opened at 9.00a.m. in Liverpool Crown Court on Tuesday 2nd April, 1839, and continued until 7.00p.m. Wilkins had succeeded in weakening the evidence of two or three material witnesses through stringent cross-examination. There was an adjournment of the court for thirty minutes for the defence to decide whether to call witnesses or proceed straight away to addressing the Jury. The latter course of action was taken with Mr. Wilkins surpassing himself by his speech to the Jury. He opened with his cool, quiet, deep sonorous voice, low but impressive and solemn, gaining the calm attention of the Jury to his remarks, proceeding step by step to unravel the facts, and urge upon the Jury such points as he considered important to the prisoner's case. He appealed so to the feelings and consciences of the Jury that the whole court was hushed, and paleness, stillness seemed to paralyse the whole audience there.The cattle-dealer Halliwell, overstated his evidence to the extent that Mr. Wilkins was able to shake his testimony and raise a doubt in the minds of the Jury, which lead them to believe that Halliwell was lying on oath. He also dwelt on other circumstances, the unimpeachable character of the prisoner's previous life, the uncertainty and doubtfulness of relying solely on circumstantial evidence. Mr. Wilkins also raised the possibility that some sportsmen on the moor may have fired in the mist a chance shot without seeing or intending to harm anyone. The Jury returned a verdict at 11.00p.m. When Whittle's father now aged between 60 and 70 went into the dock, they could be seen embracing each other. A rare, personal account of the Trial proceedings is recorded in the autobiography of John Taylor, Attorney-at- Law of Bolton , which was published by the Daily Chronicle in 1883. Taylor opens his account by stating that during February and March of 1839, he was engaged in preparing the defence papers of James Whittle who had been charged with 'Wilful Murder', the case causing great excitement in the local neighbourhood. He makes the very important observation that the evidence for the prosecution was entirely circumstantial!

The defendant is described as a collier employed by Peter Ainsworth of Smithill Hall, Bolton. Whittle had an irreproachable character up to the time of the event. It appears that Whittle's friends who had promised him their support and help with the costs of the defence, failed to respond at the last minute. Ironically but perhaps, not surprising, the Prosecution case was conducted regardless of cost. Taylor retained as Whittle's Counsel, Charles Wilkins, later Sergeant Wilkins, a young barrister on the Northern Circuit who was regarded as one of the most eloquent counsel in England at the time. There is evidence that Taylor was undecided whether to abandon or proceed with the defence, the sum of £50 being necessary for legal costs but was not forthcoming. However, an arrangement was made between Taylor and Mr. Wilkins, whereby he was to be paid £5 to hold the brief, with the promise of further fees should they become available. It appears that for a period of twelve months, Mr. Taylor had no contact with the Whittle family, but on sending a promissory note for the outstanding fee of £50 for defence costs, the note was duly returned signed by Whittle and his father. It was agreed to pay the amount by monthly instalments, bearing in mind that the two parties were only labourers. Taylor concludes his account by stating that he was thankful to recover the costs within five years of the trial, receiving the total sum of £48. This result was proof that the Whittle family had a lasting remembrance of the services of their young attorney.

CHAPTER THREE.

A RE-ASSESSMENT OF THE CASE.

In this final chapter, my aim is to present readers with an overview of the case, to enable them to draw their own conclusions based upon an examination of the available evidence. In effect, I am placing the reader in the position of that of a potential juror. By way of conclusion, I suggest several hypotheses which the reader may wish to consider, in deciding whether or not the only suspect in this tragic case was in fact innocent or guilty. The re-assessment of the case commences with an examination of the known movements of the two principal players in the case; the victim George Henderson and the suspect James Whittle. The main sources of information are those provided by contemporary press reports of the incident. There are obvious limitations inherent in these sources, the main ones being repetition, sequential errors and of course, journalistic bias. However, as a counter-balance to these limitations, we are fortunate in having as an independent source, the account of both the preparation of Whittle's defence and the subsequent trial, in the autobiography of John Taylor, Whittle's attorney.

Henderson's Known Movements.

The actual route taken by Henderson on the Friday morning from Blackrod is somewhat speculative, but there was a well-known track leading down from Blackrod towards Horwich passing through Anderton Hall Farm. This track continued through the area of Horwich known locally as Old Lord's Heights. This track emerged onto the Pike Road near to what was originally the Sportsman's Arms. This was built around 1817 to cater for sportsmen who came shooting on the moors. The inn was finally demolished in 1920 and replaced by a large cottage known locally as “Pike Cottage". The track continues alongside the cottage onto the moor and runs very close to Two Lads Cairn, eventually emerging onto the main Winter Hill road. The first reference we have concerning Henderson's movement is from a Thomas Rutterworth, a fellow packman living in Blackrod. He had observed Henderson on the Thursday evening at the Old Cock Inn at Blackrod where he had stayed the night. He saw him leave the inn at approximately 8.00a.m. on his journey in the general direction of Horwich. The last known reference to Henderson is when he arrived at Garbutt's beer-house at about 12.00 noon. He did not stay there long before making his way up towards the summit of Winter Hill on his way to Belmont.

Whittle's Known Movements.

8.30. a.m.

| Between Garbutt's and Entwistle Lane with gun.

|

9.10. a.m.

| In the vicinity of Garbutt's with gun. |

| 10.30. a.m. | Between the Stumps and Winter Hill Tunnel with gun

|

| 11.00. a.m. | In the Cabin at Winter Hill Tunnel with gun. |

| 11.30. a.m. | Between a coal-pit and Five Houses with gun. |

| oon. | .

|

| 12.20. p.m. | Seen coming from the direction of Horwich.

|

| 1. 30. p.m. | Arrived at Horwich Moorgate Inn with gun and |