Pharmaceutical Retailing and Blackburn before the Great War

Pat Fisher

The first chemists as we know them today, could be said to originate from the old grocer shops that sold spices, herbs and other items. These were run generally by a group of people called apothecaries. From about 1617 they tended to split in two groups: the trading and non-trading apothecaries. The non-trading ones tended to become general practitioners and the trading apothecaries concentrated more on the dispensing of medicines.

From 1688 up to the 1780s this period was known as the great age of quackery both here and abroad. People at this time still believed in magic and mystery. The medical profession at this time consisted of any one from a wise man or woman, in the outlying villages at one end of the scale, or a street herb seller, to a general practitioner or physicians at the top end of the scale, with a whole range of curers in between. Each concentrated on one particular type of ailment e.g., a Bonesetter, a cancer curer, or a Dropsy doctor. These medical curers were well established in society.

In 1780 it was estimated that the sales value of patent medicines was £187,500 a year. This showed just what a profitable business it had become; profitable enough for the government to impose a tax or stamp duty on all patent medicines. The more astute quacks however turned this to their advantage, claiming that the stamp on the packets was a stamp of approval by the government. The tax was not removed until 2 September 1945. Although the tax was the first legislation against quack medicines, it was not very successful. Not until 1858, with the introduction of registration and stricter control of chemists, did more orthodox medicine began to gain ground.

There is a record of three known chemists and druggists operating in Blackburn in 1793. They are Henry Bolton, a druggist who had a shop on Northgate, Christopher Rogerson, a chemist and druggist who died in April 1882 aged 71; but the location of his shop is not known, and James Wraith a chemist with a shop on Darwen Street, and who died in 1806. By 1818 there is another record of a chemist, Benjamin Abbott.

Patent MedicinesThe term patent medicine had been taken to mean not just the medicines covered by letters of patent, but to encompass all types of medicines covered by any form of trade mark at all. Many of these patent medicines became nationally known, and one or two even internationally as for example the 'Pink Pill' or the vegetable compound. This was sold to a Mrs. Lydia Pinkham, by Mr. George Todd for relief of a female weakness. This was improved then sold commercially by Mrs. Pinkham. Even after the death in 1883 of the original inventor, George Todd, it still had very strong support from the public. It was eventually introduced to Britain, and was even commemorated in songs that were sung by American and English medical students. Finally, if that wasn't fame enough, in the late 1960s the song became a pop hit under the title of 'Lily The Pink'. There were many other patent medicines that became well known nationally. Other 'secret' remedies remained restricted to localities. To give some idea of nationally known patent medicines, the following is a list of a selected few, giving names and the approximate dates at which they were first thought to have been introduced to the public.

Godard's Drops - 17th Century

Opium pain killer - 18th Century

Hooper's Revival Pills - 1743

Dr. James' Fever Powder - 1747

Godfrey's Cordial - 18th Century

Joshua Ward's Paste - 18th Century

Morrison's Pills - 1820s onwards

Holloway's Pills - early 19th Century

Holloway's Ointment - early 19th Century

Page Woodcock's Pills - early 19th Century

Parr's Life Pills - 19th Century

Dr. Mainwarine's Pills - 19th Century

Patent medicines were bought by all social classes in the nineteenth century. One of the earliest patent medicines was Dr. James' Fever Powder. This was thought to have first been introduced onto the market in 1747 by 'Doctor' Robert James, and was made mainly from antimony and cream of tartar. It was said to have sold 2 million doses in 22 years. There seemed to be quite a few secret local remedies as well, Eno's Fruit Salts by James Crossler Eno (1820-1915) from Newcastle-on-Tyne. Nurse Harvey's Gripe Mixture from Barnsley, and Kempo, made by a Leeds chemist. On looking through a range of our local newspapers from 1876-1926, I found no evidence of any sort of local remedies or patent medicines specific to this area. Most of the adverts were for national patent medicines.

However, this does not mean that there were no local patent medicines for this area, it just means that they were not advertised in the papers, and other forms of advertising were used. Another source tells us that Well's stomach mixture and Well's Blood Purifier became famous. Well's is listed in a trade index in Blackburn. Also, we do find from adverts that there were doctors or curers from out of town, who rented rooms in public places, e.g. a room in an hotel, as a consultancy, advertising the day and times when they would be in town. A survey was done on newspapers in the Bristol area which revealed various ploys used to mislead the public. Out of 50 adverts, 28 mentioned the word "Doctor", implying that a doctor had approved of the ads content. Other adverts from the Bristol examples claimed the proprietor was a doctor, gave a use in orthodox medicine, or a medical authority was quoted or doctor's testimonial stated. In the sample of adverts in Blackburn newspapers, all these ploys are to be found.

There is to be found a letter from a grateful patient to the doctor, saying the user was not cured until they used a certain brand of patent medicine. This would seem to be a very common way to mislead the public into buying the medicines.

It is estimated Thomas Beaching (1820-1907) spent £22,000 in 1880 and £120,000 in 1891 on advertising. One enterprising technique was to be seen on the sides of bathing machines in holiday resorts, in this case for Beacham's Pills in the 1890s. This can be seen in the great number of pictures taken of coastal resorts around this time. The prices of the medicines reflect the tax or stamp duty paid on them. The tax was based on the price of the article to be sold. On any item up to 1s the cost of the tax was 1½d. On goods between 1s and 2/6d tax was 3d. Between 2/6d and 4s the tax was 6d, from 4s to 10s the tax was 1s, from 10s to £1 the tax was 2s and anything above £1 the tax was 3s. That was why the price of a box of pills would be priced at 1/1½d. (i.e. 1s+tax) or the cost of a large jar of ointment was 2/9d (2/6d+tax).

A report by the British Medical Association estimated that in 1908 patent medicines, out of 41,757,575 stamped for tax, 33,037,202 were selling for a shilling or less. This meant that more than three quarters of all patent medicines sold were sold at a shilling or less. And in 1908 the industry was estimated to be worth £3 million a year. Another estimate from Holloway's book puts the value of patent medicines sales at £600,000 in 1860, £3 million in 1891 and £5 million in 1914. There was much opposition to patent medicines, particularly from doctors who felt that these undermined their reputation. The truth was however that although many patent medicines were looked upon as quack remedies and were condemned by doctors, they had nothing better themselves to offer to the public. This can be shown by the fact that as late as the 1920s or 1930s, when the National Insurance Committees were relieved of the need to pay stamp duty on any patent medicines prescribed by a doctor, the Blackburn Insurance Committee welcomed this as it would result in great savings for them! This shows that while doctors condemned and attacked patent medicines they were still making widespread use of them.

The Shops

The first shops were the type run by the apothecaries between about 1785-1800. These were a corner shop type general store and sold such items as tobacco, soap, candles, printed fabrics, and beer and spirits among other things, as well as patent medicines of the day. The first chemists and druggists shops that took over as the apothecaries dwindled, were at first a type of workshop surgery, stores and living quarters all combined. These gradually became more refined and concentrated on the shop part. The chemists began first by using the windows and window displays to attract customers, and then by changing the interior of the shop for the customers benefit. This form of change began in Bristol and London about 1800, but did not penetrate the north until the 1840s. But by the mid 1840s, many chemists shops had big new bay windows, and window displays that were decorated with glass jars, filled with coloured water or other liquids. The interior of the shops at this time were thought to be elegant, with large wooden fittings, and chests of drawers at the back with large wide-topped full-length glass fronted counters placed either side of the shop. There were also glass fronted cabinets higher up the walls. The floor area was usually very spacious. These shops catered for the upper to middle classes and in "Blackburn And Darwen A Century Ago", when describing some of the chemist's and their shops in Blackburn in 1889, much emphasis is placed on the elegance of the shops and of the high quality goods stocked and sold. The evidence of their interior design can be seen from the reconstruction of chemists shops taken from various parts of the country, for example the one that was saved from destruction at Liverpool when the owner ceased trading there, and which is now preserved at the County and Regimental museum at Preston. Or take the two old chemists shops from Leeds that have been preserved, one being housed at Kirkstall Abbey just outside Leeds, the other one at Wilberforce House Museum in Hull. Although these three examples show roughly the same design and layout they do vary slightly in detail, so we can assume that all chemists of the Victorian period were designed roughly to the same pattern.

The Equipment Used

At this time the shops would make up all (or most of) their prescriptions or remedies and make their own medicines or pills as well. All these were made from raw materials. The chemists therefore needed all the right equipment. There would be possibly two types of scales. Big brass beam scales for weighing out the larger quantities, but for more accurate and smaller measures hand scales would be used. Eventually the hand scales were replaced by even more accurate bench scales. From 1847 onwards metal weights shaped like lozenges or coins were introduced. Then there would be the measures for the weighing of liquids. These would have been made from glass and have the marks of the measures etched onto them. Sometimes translucent horn was used instead of glass but not many of these have survived. For large amounts of liquid there were pewter or copper measures. Of course, no chemist would have been without the mortars and pestles used for crushing dried herbs, mixing powders or crushing crystals to powder etc. These were always present. Some were made of glass but others were made of metal. The danger here though was that the metal might react with the chemicals being used, and so contaminate the drug mixture. Eventually ceramic ones were introduced by Josiah Wedgwood, and came into use about 1870.

The simplest medicines were the powders, with the ingredients reduced to powder by grinding, and then hand-wrapped into individual portions. But an unpleasant taste was a disadvantage. This was why pills were made instead. These pills were mixed with liquorice powder and just sufficient liquid glucose to form a pliable mass. At first they were made by hand, being rolled on a tile into a long pipe. This was divided by a spatula into smaller lumps, and rolled between the finger and thumb into small globular balls. Later, pill machines, made of mahogany with brass runners and cutters, were used. The pipe of medicinal paste was placed as a long strip along the runners on the bottom half of the machine. The bottom part of the machine being divided into runners at one end and wooden draws at the other. The top half of the machine consisting of a two handled cutter which was brought down on the bottom half and rolled to and fro, until the spherical pills were rolled in to the draws at the other end of the bottom half. These pills were then brought back on to the tile and were rounded off by hand, using an iron rounder. They were left to harden and then varnished. Finally, the pills were sometimes silvered or gilded. This was done by placing a little silver or gold leaf in gum mixture in a spherical container, and adding the pill one at a time to the mixture.

Another way of disguising the taste of powders was to place them between two pieces of rice paper, and moisten the edges so that the rice paper would stick together holding the powder in between, to produce "wafers". It was from these wafers that cachets were developed. In the later part of the century cachet machines were evolved, to help make these cachets quicker. These cachets seem to be a similar shape and idea to the sweets known as flying saucers. They were made by two semi-circular pieces of rice paper, stuck together with an outer ring of rice paper filled with powder. In our case of flying saucers, the powder being sherbet powder! Later, moulds were used to make suppositories and pessaries, containing medicaments in a base made from cocoa butter, glycerine and gelatine. Some pessaries of much larger sizes were made for horses and other animals. The requirements of vets was a side line of the chemists.

Other Sidelines

Although just over half the trade of chemists involved the selling of patent medicines and making up their own prescriptions, they were involved in many other activities too. Part of their trade was the selling of drugs without prescriptions, supplying families with the ingredients for their own recipes, and the re-stocking of medicine chests for middle-class families. The chemists made their own prescriptions for medicines for animals, particularly for horses. The coming of the railways increased the use of horses in the towns. In 1902 it was said that there were about three and a half million working horses in Britain, mostly in urban areas. The chemists therefore enjoyed considerable trade in this side of things, making and selling horse medicines and horse powders, as well as sometimes selling other vet's drugs. In the Blackburn Standard of 1876 there appears an advert under the heading "HORSE HEALTH CONDITION" which recommends the use of Richmond's celebrated condition and worm powder for horses (given mixed in food), is now being sold by all chemists. Other side lines included the perfumery trade of which the chemists had quite a large range. We know for example that Eau de Cologne was available at this time. There was also a selection of soaps and toiletry articles, just as the chemists of today sell these things

Another quite important aspect of this time was the growing trade for articles and requirements associated with babies and invalids. This meant the chemists stocked many brands of infant foods, teething powders, soothing syrups, feeding bottles, feeding cups and a variety of invalid feeders and other items associated with the sick room. Yet another side line was the selling of trusses, surgical appliances and elastic stockings etc. All the sort of things we would now buy from surgical suppliers.

The chemists were also said to sell such items as hairbrushes, dressing combs, nail brushes, tooth brushes and powders and shaving brushes. They also stocked mineral waters and cordials such as ginger beer and fruit essences. One chemist in Blackburn became well known for his own brand of baking powder (Mr. Farnworth) and another for stocking seeds, gardening tools and suchlike (Mr. Ainsworth).

Chemists in the Wider Sense

The laws and regulations defining foodstuffs and chemicals were more lax than today, and consequently many chemists sold what we would now consider foodstuff. The chemists also had a trade in spices, vinegars, sauces, pickles, cigars, snuffs, oils, dyes, varnishes, starches, as well as tea, coffee, cocoa, fruit essences and jams. Later on in the century they became involved in photography and the development of prints. Because of the variety of substances and less insistence on the separation of chemicals and foodstuffs, it was a lot easier for pharmacists and chemists to start mixing things and experimenting. This led to a whole range of new products. In 1858 an English chemist, Perkin, discovered a new aniline dye that could be made from coal tar. Although the colours were crude at first, they were later improved, and coal tar became a new source for dyes. Then there was a pharmacist in London, Frederick Benger, who became famous for Bengers Foods. George Weddell was a pharmacist, and he and his partner, Joseph Wilson Swan, experimented with salt and came up with a way of drying salt to stop it absorbing moisture, and so we have our first dry powdered table salt. The two pharmacists were from Newcastle-Upon-Tyne, and the trade name they came up with was "Cerebos". In the illustrated London News of 14 April 1853 is to be found an advertisment for bread without yeast. This is the first reference to Bird's Baking Powder. Alfred Bird was a chemist/druggist in Birmingham in the middle of the 19th century, and it was only because of his wife's disorder that he started these experiments.

He later went on to produce Bird's custard powder, the first eggless custard. James Crossley Eno became famous for his fruit salts, and John Walker from Stockton-On-Tees, first a surgeon and then a pharmacist, became famous for his brand of John Walker Matches. The famous names of Mineral waters and drinks that are still with us today all originated as pharmacists - Caley, Idris and Schweppes. Another one that started by selling proprietary medicines in London was Godfrey's Cordials. Hudson who was a pharmacist in West Bromwich became famous for the first dry soap powders. Joseph Goddard, who was a pharmacist in Leicester, first invented a remedy for halting sheep rot in sheep, and then went on to invent the first non-mercurial powder for silver plated articles and later silverware too. Mercury tended to dissolve the silver away! Even today Goddard's is the leading name in silver polish, silver impregnated cleaning cloths, and silver and jewellery cleaning liquids.

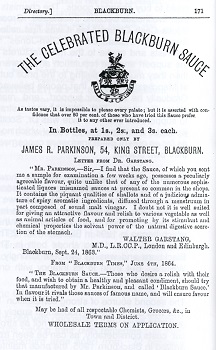

One of the brands that ought to be mentioned began in a small chemists in Worcester that first opened in the 1780s, when the owner took on as a partner a Mr. John Lea and they started making a sauce. This was to become the famous Lea and Perrins Sauce, and became known all over Britain. But was it that much different from our own local brand known as Blackburn Sauce? More to the point how many people know of Blackburn Sauce, made by our local chemist - James R. Parkinson. The nearest we can get to reproducing the recipe is an advert we found for it, which I have included in the illustrations! The above are only a few of the products resulting from experiments by chemists in the second half of the nineteenth century.

The Chemists

We have read so far about the shops the chemists worked in, the sort of medicines they sold, equipment they used, other types of goods they sold and even how chemists experimented and produced other items unrelated to their trade. But what do we know of the chemists themselves? From the trade directories and other sources we know there were quite a number of them around. For example, in 1891 in Blackburn there are listed thirty-two for that year. It would perhaps be monotonous to give a full account of every one of them here, so I will pick out the more well known and remembered ones, say five or six, and say something about them. However, it needs to be remembered that our examples form an elite, as the evidence and records for the ordinary corner shop type chemists are not available.

The first of these pharmacists was well known, Mr. William Farnsworth, who also had a great reputation as a mineral water manufacturer. He first set up in business in 1841, and in 1854 is recorded as having a shop at 91 Northgate. Farnworth moved from there in 1855 to 49 King William Street, where he designed the premises with the intention of expanding his mineral water manufacturing operation. It is these premises at King William Street that are shown in the illustrations. We know that he did not live over his shop as many people did at that time, because in the 1870-7 Directories for this area he is recorded as living at 10 Limefield, and in the 1876 Directory as living at Saville Villa, 72 Preston New Road. His products included Soda, Potash, Seltzer, Lithia Water, Ginger Ale and Lemonade, which all had a great reputation. It is even said that the Princess of Wales was known to have drunk some of his brands when she and the Prince of Wales visited the town. By 1891 the business is recorded as Farnworth and Son, still at the same premises. By 1894 we have a record of a chemist and pharmacist at 49 King William Street under the name of William Farnsworth but is this Father or Son? By 1906 there is no trace of any Farnsworth in the trade.

William Butterfield was another well-‘known character in the pharmacy trade. He first set up in business in 1863 and was in premises on the opposite side of the street to where he was later to live. By the 1870s the shop is recorded as being at 69 High Street, Nova Scotia. This was one of the exceptions, in being on the outskirts of the town at that time as most chemists were located in the town centre. Butterfield conducted a large retail and wholesale trade. By 1889 he was widely known for his own preparations and mixtures, among which were his celebrated cough linctus, and "Champion" baking powder. Butterfield was also known for Butterfield's Children’s Teething Powders and Butterfield's Syrup (for infants). The firm employed travelling salesman. They sold tea, coffee, cocoa, spices, vinegar, sauces, cigars, snuffs, dyes, oils and varnishes. In 1889 the firm was said to have a delivery float, a van, horses and stables, all of which came under the attention of Mr. Butterfield himself. In 1894 the business is still recorded under the same name and address, but in 1915 the premises are recorded under a Walter Butterfield, possibly the son. By 1925 Walter Butterfield has moved premises to Hargreaves Lane, and by 1935 we have lost trace of the Butterfields altogether.

Mr. James Robertson Parkinson first set up in business in 1863, and his first recorded premises were at 54 King Street. At this time he lived at 160 Montague Street. He later moved both shop and home address, and in 1881 the shop was at 3 Ainsworth Street while he was living at 6 Strawberry Bank. By 1884 the premises had extended to include no. 5 as well as no.3. Although Parkinson mainly sold wholesale he did some retail trade. His main claim to fame lay with his manufacture of sauces, the best known were the famous Blackburn Sauce and East Lancashire Sauce.

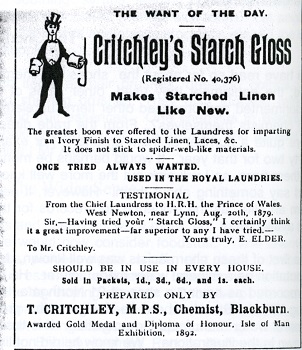

Thomas Critchley was another chemist and druggist with a shop at 10 King William Street. This is interesting in that we can trace the property from 1854 right up to 1947 (possibly further, as 1947 is the latest dates I have checked) and all that time it has been a chemist and druggists shop. It was owned in 1854 by a chemist, William Longsdale from whom Thomas Critchley took over in 1863. He left the property to a Charles Critchley between 1925 and 1935. Charles Critchley was still there in 1947. Thomas Critchley became famous and made his name as a starch and glass manufacturer, as well as being a chemist and druggist, and a seller of patent medicines. Critchley’s famous starch was said to be far superior in quality to other makes.

Advert for Critchley's Starch Gloss

By 1925 the firm had acquired two more premises, 19 Cardwell Place and 2 Finch Road, as well as maintaining the shop in King William Street. By 1935 Charles Critchley was running the business.

William Wells is the last of the chemists that we have room to mention here. He first set up in business in 1872, at 69 Higher Eanam. In 1881 was recorded at living at 14 Audley Terrace. He is recorded in the book as "By Exam", which in those days was very unusual as exams were not compulsory. Wells became famous by selling his own brands and local remedies, known as "Well's Stomach Mixture" and "Well's Blood Purifier". He also invented a new type of feeding bottle, "Well's Baby Feeder". By 1915 we find he had ceased to trade but sold the premises to another chemist and druggist, Mr. William Henry Grimshaw. Between 1935 and 1939 the business passed to a relative, May Grimshaw who is still recorded there in 1947.

Competition to the Chemists

Right from their early development, chemists were faced with opposition from other sources. At first this would be from fringe medicine and cults having their own remedies. In 1891 there were listed 19 herbalists practising in the Blackburn area, apart from 32 orthodox chemists. Other opposition would come from travelling herbalists, or quacks, and street traders and market stall holders etc. Right up to 1910 there is evidence of a lot of travelling chemists and quacks who stopped for short periods in the town. According to a 'Report as to the Practise of Medicine and Surgery by Unqualified Persons in the United Kingdom'. In Accrington it was stated that though there was no increase, these practices had remained high for the last number of years and was causing a formidable amount of bad effects on the health of the general public. In Blackburn, it was said to be not increasing but staying at a constant level.

This, combined with the fast growth from 1850s onwards of big new department stores, such as the co-op, civil service co-op stores, W.H. Smith, Lipton's, Freeman Hardy & Willis, etc began to form a considerable force of opposition to the chemists. As mentioned earlier, there were still market traders as well to contend with. In 1897 we get a complaint to the council from the market superintendent as to the disturbance caused by itinerant vendors of medicines, and drug sellers who were shouting and calling out and being troublesome in order to attract people to but their wares. To add to all this there was another problem for the chemists. In 1875 the cost of a medicine license was reduced. This meant that more people could obtain a license enabling them to sell drugs or medicines. In 1874 the number holding this license was about 13 thousand, by 1884 it had gone up to almost 20 thousand. Most of this increase was to competitors of the chemists.

Because of the growing numbers of retail outlets for patent medicines some of the bigger stores started to cut the prices, and sell them at cost as 'leading lines' in order to draw people into their shop. This created a cut-price war as people would go wherever they could to buy cheaper goods. The chemists and pharmacists could not compete with this and their livelihoods became threatened. Grocer's shops also cut their prices. Big firms such as Boot's Cash Chemist (as it was first called) and William Daye's in the South led the way. Eventually William Samuel Glyn-Jones, formed an association which included the small chemists and spoke to the manufacturers on behalf of the chemists, saying if they wanted the support and the reputation and guarantee of the selling of medicines from the chemists then they must stop selling to the price cutters. He first spoke to the manufacturers in 1896 at Manchester, stating that people believed it was more reputable to buy from the chemists. Gradually he won their support, and manufacturers stopped supplying Boot's and the big stores like them. This did not happen straight away though. One of the first manufacturers to support the chemists side was Dr. Scott's Liver Pills. By 1900 it was accepted that there would be a minimum price below which no person would be allowed to sell anything, at least as far as patent medicines were concerned. This paved the way for the likes of Boot's to sell their own brands.

But while this was going on nationally, how did it affect the chemists in Blackburn? Although Boot's and William Daye's were the leaders of this campaign in the south, there was as yet no Boot's in Blackburn and as far as we know there has never been a branch of William Daye's here. The first record of Boot's in Blackburn was in 1905 when all this trouble had finished. The first competitor at this time seems to have been Taylor's Drug Stores which began in 1894 in Blackburn at 12 Thwaites Arcade. It later became Taylor's Drug Co. and by 1915 had two shops both in Thwaites Arcade. It later had three branches in Blackburn and was to compete strongly with Boot's and eventually came under Timothy White's. But even in its infancy with only one store in Blackburn, it was still the major competitor to the chemists.

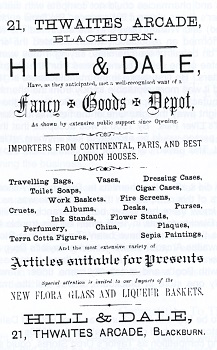

The second source of strong competition to be found in Blackburn was from Hill and Dale. This was one of the big household supply stores that had grown up about the 1870s and 1880s and although maybe not as strong competition as Taylor's Drug Stores, could still cut costs considerably, as can be seen from adverts I have found. By the time Boot's arrived in Blackburn in 1905 the price maintenance war was over. This still holds good on proprietary medicines today.

So, what then were the factors that led to changes during the period under consideration? The chemists were susceptible to the influence of consumer fashion and were therefore affected by various outside factors. Many of the factors which bought the greatest changes to the chemists were ones over which they had no control. They were affected firstly by the importation of American ideas and trends, and which led to fringe medicine cults being formed in Britain, e.g. Coffinism which led to the cult of the medical botanists. The chemists were also greatly affected by the growth of the patent medicine industry, which of course depended on the whim of consumers at any given time, despite the publication by the British Medical Association of the hostile 'Secret Remedies' and 'More Secret Remedies'. The patent medicine trade still thrived and these books seemed to have little affect on the population.

The chemists were also affected by the price cutting war, in which they were forced to fight back just for self-preservation. The National Insurance Act of 1911 had major effects on the chemists as it gave them for the first time sole rights for the dispensing and selling of remedies for the majority of working men and women. This in turn was responsible for a complete change in the type of medicines sold, and in a general way led to the gradual reduction of quack or patent remedies. Stricter controls, poison regulations, and the introduction of qualifying exams were also a consequence of the National Insurance Act.

Hill and Dale Advert The Celebrated Blackburn Sauce

Sources

Primary

Blackburn Trade Directories (various) 1818-1947

Blackburn Newspapers (various) 1874-1926

Blackburn Council Minute Books

Insurance Committee Minute Books (Lancashire Record Office)

Report As To The Practice of Medicine and Surgery by Unqualified Persons. HMSO, 1910

Round The Coast 1895

Secret Remedies, BMA 1912

More Secret Remedies, BMA 1912

Secondary

Blackburn and Darwen a Century Ago. Alan Duckworth. Landy Publishing 1989

The Royal Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain 1841-1941: A Political and Social History. F W Holloway

Magic Medicine and Quackery. Eric Maple

The Victorian Chemist and Druggist. W A Jackson. Shire, number 80

Blackburn in Old Picture Post Cards. Peter Worden and Robin Whalley

Antiques of Pharmacy. Leslie G Matthews

Regional Guide to Pharmacies Past. Leslie G Matthews

Pharmacy in the Wider World. Leslie G Matthews

Blackburn Worthies. G. C Miller

History of Blackburn. Durham

A Blackburn Miscellany. Bob Dobson (edited). Landy

The History of Everyday of Everyday Things in England 1851-1934. Marjorie and C B H Quennell

Blackburn Local History Society Journal 2000-2001. Page 36.

Transcribed by Shazia Kasim