Dr Robert West Pearson

The Scandalous Life of the Rev. Robert West Pearson: Over-reaching Ambition or 'A Bad Egg'?

Introduction

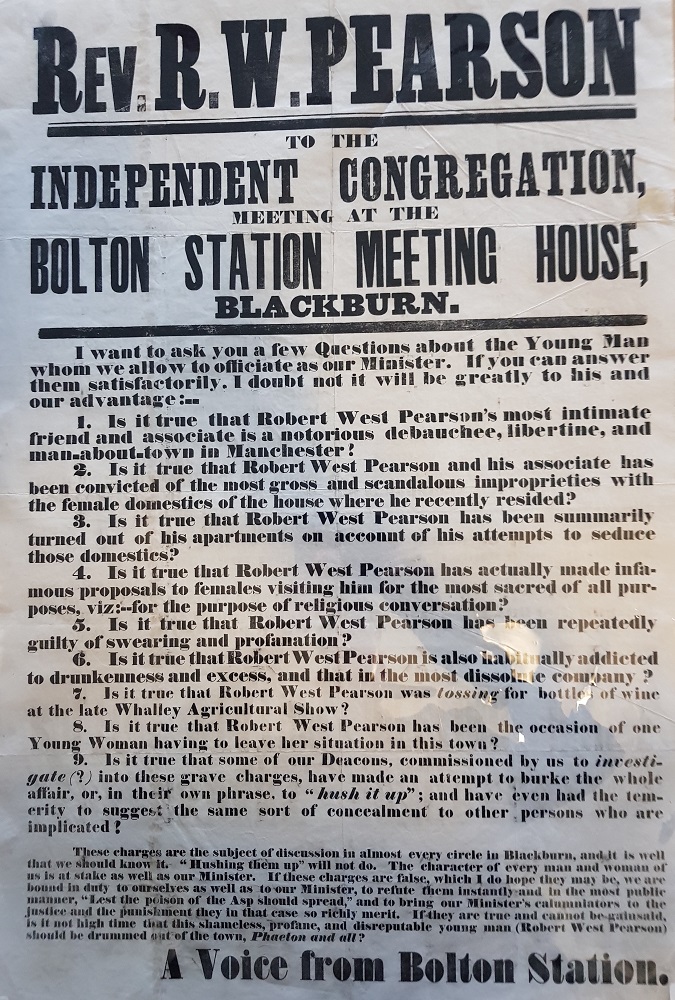

Amongst over 700 items of ephemera held by Blackburn Central Library is a poster entitled 'Rev. R. W. Pearson' addressed 'to the Independent Congregation meeting at Bolton Station Meeting House, Blackburn'.[1] In the poster, which is undated, 'A Voice from Bolton Station', using a series of questions, accused Rev. Pearson of drunkenness and sexual impropriety with servants and female members of his congregation. Also, the anonymous author accused some of the church's deacons of trying to conceal Pearson's misdemeanours. Research revealed that the subject of the allegations was Robert West Pearson who was minister for an independent congregation based at the old station on Bolton Road between 1862 and 1864. The poster was almost certainly published during the late summer or autumn of 1864 when the affair was the subject of several letters published in the Blackburn Times. Further research revealed Pearson's complex life in which success and failure related to scandal were never far apart.

Pearson was born in Manchester in 1838 into a family that worked in the textile industry. Through academic ability Pearson, who had worked as an errand boy, entered Owens College in Manchester where he was a successful student. After Owens College his preaching ability aroused interest from major non-conformist congregations in London and Liverpool. However, his hopes of becoming co-pastor in London or Liverpool chapel were dashed when it was discovered that his claim to hold both a Ph.D. and an M.D was bogus. Pearson's first brush with scandal aroused national interest. During that scandal Pearson accepted a pastorate in Blackburn, which he resigned when news of the scandal reached Blackburn. This incident in Blackburn revealed another of Pearson's talents, the ability to attract and keep a dedicated following even when he was the subject of scandal. The congregation at Bolton Road followed him after he resigned his original mission. Pearson's ability to win a dedicated following through his apparent intellect and preaching ability, some of whom remained dedicated even when he was in the centre of a scandal, played out several times in Pearson's life, not only in Blackburn but also in the United States. Pearson's life raises the question whether Pearson was the victim of his own overreaching or was he just a 'bad egg'? This article will consider this question by studying Pearson's life.

Early Life and Background

Robert West Pearson was born in Ancoats in Manchester during the last quarter of 1838.[2] He was the first child of Robert and Eloise Mercy Pearson, nee Williams, who married in Manchester at the Collegiate Church, now the Cathedral, on Christmas Day, 1837.[3] Although married in Manchester, neither was born there. Eloise was born in London and Robert was from Hoghton, a village 5 miles to the west of Blackburn.[4] Assessing the Pearson family's social status is problematic. Nothing is known of Pearson's mother's family or her background but that of his father can be pieced together from various sources. From the occupations given for Pearson's father in the 1841, 1851 and 1861 censuses the family appear to be from the skilled working-class, involved in the textile industry.[5] However, at the time of the marriage of the Pearsons' second son in October 1861, Pearson's father's occupation was given as farmer.[6] This is confirmed from reports in the Preston Herald in 1864, with one report giving his position as farmer and proprietor of the post office in Hoghton.[7] A study of the census returns for Hoghton between 1841 and 1871 reveals several Pearsons in the area, some of whom were farmers while others were handloom weavers and others, shopkeepers.[8] Neither Robert nor Eloise Pearson appears in the 1871 census return for Hoghton but an Alice Pearson did run the post office. It is probable that Pearson's father was related to some, if not all, of the Pearsons in Hoghton. His origin would then have been from small scale farmers who supplemented their income with handloom weaving, a section of rural society that experienced economic and social decline during the early nineteenth century when the development of the power loom undermined handloom weaving and young people moved to towns leaving weaving villages, such as Hoghton.[9] Such small scale farming families who were also skilled handloom weavers enjoyed a good income and were independent whereas even skilled workers in cotton factories in rapidly expanding textile towns would have a lower standard of living and a reduced social status. It is probable, then, that Pearson's family experienced not only geographical but also social displacement during the first half of the nineteenth century. His father's experience of a period of decline in social status could have contributed to Pearson's ambition.

Site of Owens College, Quay Street, Manchester (c) David Hughes, 2018.

By 1841, the Pearson family had moved from Manchester to Chapel Street, Blackburn, where their second son, William Henry, was born at the beginning of 1841.[10] After living in Blackburn for a time, the Pearson family returned to Manchester. In 1851, they were lodging in Hulme where, at the age of 12, Pearson worked as an errand boy.[11] As well as working Pearson must have received an education above the norm for someone whose father worked as a warper in a cotton factory because in 1856 he enrolled as a student at Owens College in Manchester.[12] Owens College was founded in 1851 after a bequest from the industrialist, John Owens, to form a college providing academic scholarship to prepare young men to proceed to the University of London to obtain a degree before embarking on careers in the professions. All students had to pass an entrance examination which demanded a high standard of education. In the opinion of the college's professors the institution struggled to recruit students because Manchester's schools did not provide an education that prepared students for the independent scholarship which Owens College promoted.[13] Pearson must have received an education that enabled him to pass such a rigorous entrance examination. That could have been because Pearson wanted to escape factory work or it could have been his parents who wanted him to better himself.

Plaque on site of Owens College, Quay Street, Manchester (c) David Hughes, 2018

Pearson was a successful student and came under the influence of Rev. A. J. Scott, the first principle and professor of English Language and Literature, and Moral and Mental Philosophy. Although the competition was not fierce, Pearson won prizes at Owens College in 1857, 1859 and 1860. At the end of his first year in July 1857, Pearson won two prizes for chemistry, including the Dalton chemical prize, but the prizes he won in his last two years proved to be more significant. In July 1859, Pearson won the prize for comparative grammar, with second-class certificate in logic, and in June 1860 he won the prize for logic and philosophy, and a second-class certificate for the Hebrew bible. Rev. A. J. Scott awarded all these prizes.

Alexander John Scott (1805-1866) was not only an academic but also a controversial Scottish Presbyterian minister and theologian. Scott was a graduate of Glasgow University and Glasgow Divinity Hall who moved to London in 1828 to become minister at the Scots Church in Regent Square. Here he was introduced to the poet, Samuel Taylor Coleridge, and the writer, Thomas Carlyle. However, Scott's time as a minister did not last long because he had his licence to preach withdrawn on the grounds of heresy in 1831. After his ejection by the Presbyterian Church, much of Scott's congregation followed him to form an Independent congregation. In the late 1820s Scott developed teachings which would mark the first appearance of modern Pentecostalism, which included people speaking in tongues. Under Scott's influence the first charismatic religious outbursts happened in Port Glasgow in 1830. Scott came to reject such outbursts as religious hallucinations but he remained an influential teacher as well as a powerful preacher. In 1848, just before he moved to take up his position at Owens College, Scott became one of the founders of Christian Socialism, along with Charles Kingsley, the author of the Water Babies.[14] As will be seen from his later career, Pearson not only learnt some of his ideas from Scott but also absorbed the lessons of Scott's preaching, charisma and the ability to attract dedicated followers.

The “Doctorates" Scandal

After finishing at Owens College, in June 1860, Pearson could have followed the path for which his education had prepared him, a degree from the University of London followed by formal training for the non-conformist church before taking up a ministry. At first, Pearson appeared to follow a normal route to the nonconformist ministry, by enrolling with the Cavendish Theological College in Manchester which Rev. Joseph Parker founded during the summer of 1860. Parker was the minister at Cavendish Street Congregational Church, a position he took up in 1858 after moving from the Congregational church in Banbury, Oxfordshire. Parker took a personal interest in Pearson, probably because he saw something of himself in the new student.

Parker was born in Hexham in Northumberland in 1830, the son of a stonemason. At the age of 12 he began to learn his father's trade but soon returned to school. After leaving school he continued to educate himself until he was 21 when he became a deacon for the local Congregational Church, although he preached his sermons for the Methodists. After joining the Congregational church he felt called to the ministry. Parker wrote to Dr. John Campbell, the minister at Whitefield's Tabernacle in Moorfields in London.[15] Campbell invited the young Parker to preach three sermons, after which Parker was appointed Campbell's assistant. While in London, Parker attended courses at the University of London before moving to Banbury to have his own congregation at the young age of 23. Parker gained a reputation as a great preacher. Parker's reputation was enhanced further after he moved to Manchester. Often he filled Cavendish Street Church, preaching to around 1,700 people. With Parker's popularity as a preacher, his congregation increased, including many wealthy leaders of commerce and industry.[16] Possibly, Parker saw the young Pearson as his protégé, just as he had been that of Dr. Campbell, in London. Maybe he saw Pearson following a similar path in the Congregational Church but Parker was to come to regret adopting Pearson.

Pearson was one of eight students who enrolled at the new Cavendish Theological College. As well as Parker, the tutors were J. B. Patton, M.A, a young minister from Sheffield, and J. Radford Thompson, M.A. from Heywood, near Manchester. The students received a formal education, including instruction in theology, philosophy, and English language as well as preaching and active work in the community. The length of study was to be determined by the ability of each student with the maximum being 3 years. Parker declared in a pamphlet proposing the college that 'the students will be taught the dignity of labour; and will be so trained as to develop a manly, aggressive and enterprising spirit in regard to the moral conquest of British heathendom and the evangelisation of the Colonies and Pagan countries'. Maybe Pearson heeded this too well because his aggressive and enterprising spirit was to lead to a scandal that gained national coverage and his expulsion from Cavendish College.[17]

After only a few months at Cavendish College, Pearson began to seek a position in the Congregational Church. In the spring of 1861 Pearson preached several times at the King's Weigh House Chapel, in London, an important Congregationalist church consisting of young businessmen, the middle classes and some wealthy people.[18] Pearson's preaching received several positive reports in The City Press in London. It was reported that the congregation appointed Pearson the co-pastor in June 1861.[19] If these reports were true, Pearson never took up the position. The reason for this is not known but it could have been because of reports about Pearson emanating from Liverpool.

During the period Pearson was a candidate for the co-pastorate at the King's Weigh House, Pearson was being considered as assistant minister at Great George Street chapel in Liverpool.[20] During his time in Liverpool, Pearson preached two sermons. At first, the sermons were well received but, then, rumours began to circulate that both sermons had been plagiarised. Pearson denied the accusations but a committee of investigation was appointed. The committee found that the structure of one sermon was the same as one published by Rev. Alexander McLaren but the text of Pearson's sermon differed from that of McLaren. However, the text of the second sermon was found to have been drawn from one by McLaren, the only differences being extracts taken from other sermons by McLaren published in the same volume. The committee members had no doubt that Pearson knew McLaren's sermons and were sure of Pearson's plagiarism.[21] After this investigation, doubts began to arise about Pearson's claim to hold a Ph.D. and an M.D at the age of 22. At first Pearson said that he had gained his doctorates at the University of Edinburgh, which, later, he changed to Erlangen in Germany. Christian D. Ginsburg, a missionary working in Liverpool, was amongst those who were suspicious. Ginsburg wrote to the Pro Rector of the University of Erlangen enquiring if a Robert West Pearson had been a student at the university and if he had been awarded a Ph.D. and an M.D. The Pro Rector replied stating that Pearson had never been a student and had not been awarded degrees from that university.[22] Pearson refuted this in a letter published in the Liverpool Mercury but, then, the scandal escalated drawing in his mentor at Cavendish College, Rev. Parker. As it developed, the scandal received national coverage.[23]

Shortly after Pearson's denial of Ginsburg's allegations, the Manchester Examiner reported that a Cavendish College Committee received a letter from Pearson stating that the diplomas were spurious but that he had been deceived. Pearson admitted that he had bought the diplomas from a German in Manchester during his final year at Owens College.[24] Until Pearson made this admission, the Rev. Joseph Parker had defended Pearson but, after the confession, Parker argued that Pearson had been duped by a foreigner and betrayed into sin. Cavendish College Committee expelled Pearson, despite Parker's belief that Pearson had been duped.[25] After the Committee's investigation, Parker could no longer support Pearson but he excused him because 'he is yet very young; he is possessed of powers which, in my opinion, are truly extraordinary'. Parker ascribed Pearson's failings to ambition.[26] Parker became the first of many who continued justify Pearson's behaviour even after irrefutable proof of Pearson's misdemeanours.

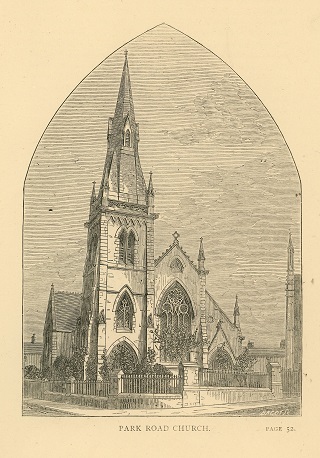

Not everyone admired Pearson. An anonymous editorial in the Liverpool Daily Post entitled '"Doctor" Pearson' was scathing in its criticism.[27] The author dismissed 'the exposure and downfall of a young man who borrows his sermons and wears fabricated academical honours' as 'nothing very remarkable'. Instead the editorial concentrated on the reason for Pearson's success: his preaching. The author dismissed Pearson's preaching as 'purely sensational, with the infusion of much ambitiousness' and criticised 'the shouts and whispers of a melodramatic actor'. However, the writer of the editorial had an agenda beyond dismissing a young preacher with 'gab-giftedness', Pearson's preaching was used as a vehicle to criticise the lack of culture of congregations who admired such preaching with the author advocating 'natural and plain preaching with a stronger development of the devotional and ritualistic element of Divine Service'. This is a patrician, Anglican rejection of populist, evangelical worship that appealed to the working class and elements of the middle class. However, the prediction that 'we doubt … Mr. PEARSON will find any congregation anxious to enjoy his ministrations' proved to be wrong as the gab-gifted Pearson had been offered, and accepted, the pastorate at Park Road Church in Blackburn while the scandal was raging.[28]

Ministry in Blackburn and Scandal

Pearson arrived in Blackburn towards the end of October 1861 where, on three successive Sundays, he preached sermons. The congregation at Park Road Church found Pearson's sermons to be 'eloquent and impressive' just as the congregations at the King's Weigh House and Great George St. Chapel had done before. As a result, Pearson was offered the pastorate, which he accepted. Soon after Pearson accepted, news of doubts about his qualifications reached Blackburn with the Blackburn Standard reprinting correspondence between Ginsburg and the Pro-rector of Erlangen from Liverpool Daily Post. Pearson accepted the pastorate without the permission of Cavendish College. When the college was informed this became another grounds on which Pearson was expelled.[29] Even after Pearson had been expelled from Cavendish College and his doctorates proved bogus, Pearson was not immediately rejected by the congregation at Park Road. By the middle of December 1861, a delegation of Park Road deacons visited Manchester to make further enquiries into his character and previous behaviour. As a result those who had supported Pearson turned against him. Nevertheless, a minority continued to support Pearson, so a further delegation visited Manchester. However, when they arrived, Pearson was no longer there and was rumoured to have gone to London to study chemistry.[30] And with that, Pearson ended his time as pastor at Park Road but, this was not the end of Pearson in Blackburn; his preaching and intellect continued to impress some members of the Park Road congregation.

Park Road Church, Blackburn (Abram, W.A. "History of Independency in Blackburn 1778-1878)

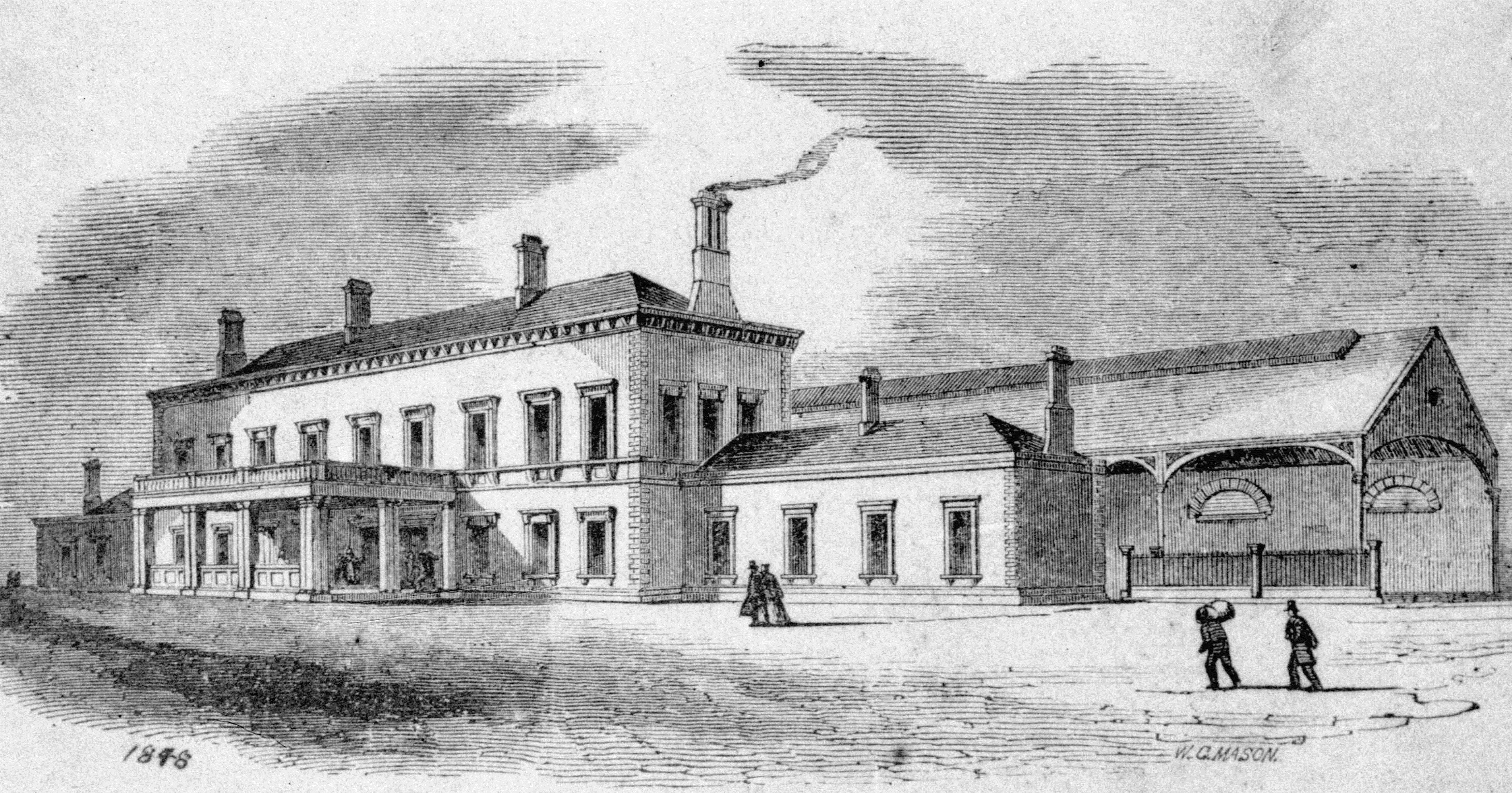

In early January 1862, the Patriot reported that a meeting of the friends of Pearson unanimously decided to recall him but another meeting voted 34 to 24 to accept Pearson's resignation with 200 abstentions. This decision was final but some members talked loudly of secession. The Patriot dismissed this as 'mere talk'.[31] The Patriot was wrong because in April 1862 the secessionists formed a new independent congregation at the Old Bolton Road Station in Blackburn under Pearson.[32] Although, at first, Pearson led the congregation as a layman by March 1863 he was styled Reverend, even though he had been expelled from Cavendish College without qualifications.[33] Pearson leading his own secessionist congregation bore some similarities to that of his mentor at Owens College, Professor Scott. However, unlike Pearson, Scott had been a minister of the Scottish Presbyterian Church before he was excommunicated and then establishing his own independent Congregation. Although, like Scott, Pearson's charisma drew a personal following that came together as a congregation.

Despite his inauspicious beginnings in Blackburn, Pearson's pastorate over his first two years appeared to be a success. By October 1863, the Sunday school had grown from 62 pupils to 450 while the church increased from 200 enrolled members to 700 regular attenders at services.[34] Pearson's pastorate had been so successful in such a short period that the church members agreed to build a new church at the junction of Preston New Road and Montague Street. Lord Teynsham laid the foundation stone on 25 May 1863 for a chapel and school that was reported to cost £8000.[35] At the annual meeting of the Independent Meeting House on Bolton Road, it was announced that by the end of March 1864 arrangements had been made to move into the new chapel which was claimed could hold a thousand worshippers.[36] However, such ambitions seemed to be unfounded because no evidence exists that a move to the new chapel happened in 1864. [37]

Old Bolton Station, Great Bolton Street, Blackburn,

(N34, Blackburn Library Photograph Collection)

As his congregation increased, Pearson became part of Blackburn's religious and public life. Pearson entered into a public argument with Rev. G. Donaldson, the curate of Christ Church, Blackburn, on 'the mother church' in late summer of 1862; in March 1863 he was on a platform in Blackburn Town Hall which included the Mayor of Blackburn and ministers of other churches; and in November 1863 he lectured at Blackburn's Rechabites Hall on American Civil War, in which he sided with the North and supported the ending of slavery.[38] After an inauspicious beginning, Pearson appeared to be thriving in Blackburn; he had a successful chapel that was building a new church and he had become part of Blackburn's public life. By the age of 25, Pearson was fulfilling his ambitions and had risen from his working class roots. Then, in 1864, Pearson became the subject of another scandal with accusations of drunkenness and sexual impropriety. Eventually, this scandal brought Pearson's downfall in Blackburn and the dashing of his ambitions.[39]

Allegations about Pearson's behaviour were set out in a poster which is now held by Blackburn Central Library. The poster, entitled 'Rev. R. W. Pearson', was addressed to 'The Independent Congregation meeting at the Bolton Station Meeting House, Blackburn' and signed by 'A voice from Bolton Station'. The poster is undated but correspondence and an advertisement in the Blackburn Times place it during July and August 1864. Using nine questions, the anonymous author alleged that Pearson was involved in sexual impropriety as well as drunkenness. The questions included veiled accusations that Pearson and a close friend from Manchester, who was a noted debauchee and libertine, attempted to seduce servants at Pearson's house. As a result Pearson was evicted and one of the servants had to leave Blackburn. Also, Pearson attempted to seduce women who came to him for religious advice. The author continued by accusing Pearson of swearing and using profanities as well as keeping dissolute company with whom he was often drunk. Finally, Pearson was accused of committing the heinous crime of 'tossing for bottles of wine at the late Whalley Agricultural Show'! The questions ended by turning away from Pearson to accuse some of the Deacons of attempting to hush up the whole affair. 'A Voice from Bolton Station' ended by demanding that 'this shameless, profane, and disreputable young man … should be drummed out of town'.

Although Pearson's actions and his connection with the Bolton Road Meeting House became the cause of heated debate in the letters column of the Blackburn Times between August and October 1864, no specific accusations were made. An advertisement placed in the Blackburn Times by Hannah Towers on 13 August 1864 sheds some light on two of the accusations in the poster: Pearson's inappropriate behaviour towards his servants and the tactics of Pearson's supporters. Towers, who had been a servant at Pearson's apartments in Duke's Brow, denied that statements posted on walls around Blackburn under her name, withdrawing accusations against Pearson, were untrue and obtained from her by fear and threats. Towers declared that she stood by her original statement. Towers' advertisement offers evidence to support the accusation made in the poster that some of Pearson's supporters were attempting to hush up the affair. Although Towers made no detailed allegations, read with the poster, it is probable that Towers was the woman who had to leave Blackburn because of Pearson's sexual behaviour towards her. It is not known when Towers left Blackburn but in 1871 she was a servant to a butcher and his family in Salford.[40]

Further details of Pearson's alleged misdemeanours emerged during a court action in December 1864 when John Scholes, the former treasurer of the building committee for the new meeting house on Montague Street, sued Pearson for outstanding payments for lodgings, and other expenses, mainly from when Pearson moved to Blackburn in April 1862.[41] Under questioning from the plaintiff's solicitor Pearson gave a confusing and contradictory answer about the circumstances under which he had had to leave his apartments in Duke's Brow. Pearson admitted that just before he left Duke's Brow he had a visitor stay with him, Mr. Sword a solicitor from Manchester who was then living in London. [42] Pearson admitted that he had had to leave suddenly but denied that it was because of his behaviour. Pearson denied that there had been a dispute between him and an unnamed woman but there had been one between the same woman and Mr. Sword. Pearson confirmed that he and Mr. Sword had to leave suddenly but insisted that they were not obliged to leave. Pearson also denied that they were drinking most of the time. Pearson's statement offers some evidence to support the allegations made in the poster: Mr. Sword could be the libertine and debauchee from Manchester; Pearson did not deny drinking; and the circumstances under which he had to leave Duke's Brow after Sword had been in dispute with a woman could hint at inappropriate sexual advances. Tower's advertisement and Pearson's contradictory statements during this trial are the only evidence supporting the accusations made in the poster.

The battle to expel Pearson from Bolton Road that played out in correspondence in the Blackburn Times between August and October 1864 provides evidence of the tactics used by some church members to hush up the Pearson scandal. A letter from 'Nemesis' published in the Blackburn Times on 26 August 1864 called for the creation of committee of investigation, including honorary membership of 'all gentlemen of influence and position in the county', into what 'Nemesis' called 'the Bolton Road scandal'.[43] He called for such a committee even though he acknowledged most of the congregation, which he observed were mainly women, refuted the allegations about Pearson. Another letter from 'Nemesis' published in the Blackburn Times on 10 September 1864 revealed that church members had formed a committee of investigation but the response of Pearson's supporters within the congregation was to expel them from the church.[44] One of those expelled wrote to the Blackburn Times, under the name 'One of the Expelled', on 1 October 1864 stating that he was one of three members expelled for calling for an investigation into Pearson's behaviour.[45] He was vitriolic in his attack on 'four obscure men, and many compromised women, who still continue to support R. West Pearson'. This letter, along with another from the same correspondent published in the Blackburn Times on 15 October 1864, said little about Pearson and much about internal church politics. Despite being expelled from Bolton Road Meeting House, the committee of investigation continued in its work. In an advertisement published in the Blackburn Times on 8 October 1864, the committee called on Pearson and the Deacons of the church to prove Pearson's innocence.[46] The committee promised a fair hearing and a public exoneration if Pearson was found to be innocent of any misdemeanours. The advertisement ended with the threat that 'if this invitation is not accepted, it will be considered that no defence can be offered'. It is unlikely that either Pearson or the deacons accepted this offer purely because the committee members had been expelled from the church. The impression given by the correspondence in the Blackburn Times is that the congregation remained at Bolton Road Meeting House but Pearson, in the court case from December 1864, stated that he had left Bolton Road in July or August taking his supporters to a new church in the recently built school on Montague Street.[47] No evidence exists to support Pearson's claim. Nightingale's brief history of Montague Street Congregational Church was vague on the precise events but he was clear in stating that church disbanded after a 'legally constituted church meeting'.[48] It is possible that Pearson and his loyal supporters moved to Montague Street in the autumn of 1864 but it is more likely that Pearson left Blackburn during the outcry about his alleged misdemeanours.

Montague Street Congregational Chapel, Blackburn (Church Bazaar Catalogue, 1902)

During his time in Blackburn Pearson developed a personal following who would continue to support him in spite of all allegations made against him. This following extended into church politics, which, at times, became personal and vitriolic, as seen in the correspondence in the Blackburn Times. As can be seen from Pearson's mentors, Scott and Parker, personal charisma cultivated passionate support that could tear a congregation apart. Pearson's personality, expressed through his dramatic preaching, helped to create such a passionate following, which had short-term disastrous consequences for the Bolton Road congregation. Blackburn witnessed the first instance of divisions that could develop between Pearson's followers; others were to follow, not in England but in the United States.

Extract from Ordnance Survey map,1894, Lancashire Sheet 62.16. 'Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland'

1865: The Year of Crisis and Change

After leaving Blackburn, 1865 was an eventful year for Pearson. During the first quarter he married Sarah Ann Dunkerley in the registry district of Swansea.[49] The reason for Pearson marrying in South Wales is unknown but what happened to him in May could offer an explanation. After his marriage, Pearson moved to Liverpool. Then, in May 1865, Pearson was in debtors' prison in Lancaster, during which time he was declared bankrupt.[50] Therefore, the likely explanation for Pearson being in South Wales was that he was in flight from his debtors. He was release from Lancaster Prison in May 1865 and he was discharged from bankruptcy in July 1865.[51] The cause of Pearson's bankruptcy is unknown although the discharge from bankruptcy of his uncle, James Pearson, in December 1865 does shed some light. James Pearson's bankruptcy was because he had stood surety for Robert West Pearson for a bill of exchange for £55 from the Manchester Loan and Discount Company.[52] It is likely that Pearson held other similar loans which, after he was driven from Blackburn and his source of income, he was unable to repay when the loan company called in the debts. After his discharge from bankruptcy, Pearson returned to Liverpool where he was robbed of 17s 9d in September 1865.[53] By the time of the culprit's trial, Pearson had left Britain for the USA.[54] This was probably the only option open to an ambitious young man who had been at the centre of two scandals, one of which had been reported nationally. His career as a nonconformist minister in Britain was in severe difficulty so moving far away was the only option available to Pearson, if he was to fulfil his ambitions and maintain the status he had enjoyed during his brief stay in Blackburn. However, a new country and a new nationality did not mean the end of scandal for Pearson.

Scandals in the USA

In less than two years after arriving in the USA, Pearson had a new profession as an attorney. In 1867 he became a member of the bar in Massachusetts and by 1869 he was appointed a Justice of the Peace in Essex County, Massachusetts.[55] Pearson continued as a J.P. until 1871 when he left the state and the country.[56] No contemporary reports about the reason Pearson left Massachusetts has been found but, according to the report in the Blackburn Times from September 1878, Pearson had to leave because 'he became connected with a number of young lawyers, a connection which, in some of its circumstances, was very painful to Mrs Pearson'. The prose of the Blackburn Times was opaque. Was the report referring to drunkenness and general sexual exploits, similar to those of which Pearson was accused in Blackburn, or was it implying that Pearson had become involved in homosexual activity with the young lawyers? If the report in the Blackburn Times was true then another scandal had thwarted Pearson's ambition and driven him from his new career.

After six years, Pearson left the legal profession to return to his first calling, the nonconformist church. In 1871 he was a Baptist minister in Montreal, Canada. By 1872 Pearson had gained such respect that he became a member of the committee of the Canada Sunday School Union. Pearson did not stay long in Montreal because by the end of 1872 he was Baptist minister in Lafayette, Indiana. Although Pearson had only just moved to Indiana, he was chosen as president of the new joint stock company that re-established Franklin College in Franklin, Indiana. Franklin College was formed in 1834 with the support of Baptists from Indiana but by the 1860s it ran into financial difficulties and the last student left in 1872. With investors from the local community and from members of the Baptist church, it re-opened.[57] Pearson's achievements as president are not known but he did use his position to gain the doctorate he had claimed, falsely, ten years earlier. In 1873 Franklin College awarded Pearson an Honorary Doctorate of Divinity, so he could style himself Dr Pearson legitimately.[58]

With his reputation behind him and with his academic status established, Pearson moved on again in July 1873 when the First Baptist Church in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, approached him to become their minister. Even though Pearson had only been in Lafayette for less than a year the Indianapolis Journal regretted 'the Baptists of this State thus lose one of their most notable men'.[59] As in Blackburn ten years earlier he soon gained an admiring followers, thanks to his preaching and personal charisma. This was to continue with his new pastorate in Pittsburgh. His congregation increased as people came to hear Pearson preach and, soon, the chapel was too small to hold the crowds. Again, following the pattern of Pearson's time in Blackburn, a new chapel was required. Unlike in Blackburn, the new chapel on Rose Street was completed at a cost of $86,000. The building was considered to be a 'magnificent structure' and had a seating capacity of 1300.[60] When the chapel was dedicated on 28 November 1876, Pearson had achieved what he had strived for in the first part of the 1860s: he was rightly styled Dr. Pearson; he was an admired preacher; and he had an impressive new chapel built by a congregation of his followers. Again, Pearson was a respected citizen but, as in Blackburn, scandal and failure was not far away.

As with Pearson's first entrance into public life in 1861, Pearson became the subject of national interest. During 1877 Pearson's behaviour became a topic of wide discussion within the United States. In a debate between Rev. G H Humphreys, a New York Presbyterian minister, and D M Bennett, the editor of a radical newspaper, the Truth Seeker, Bennett used Pearson as an example of 'hypocrisy, villainy, and … unworthiness of reverence and esteem'. Bennett claimed that a court from Pearson's church had found him guilty of 'lying, drunkenness and numerous adulteries'. In Bennett's opinion Pearson 'was emphatically what is familiarly called a “bad egg"'.[61] Bennett's claim that Pearson's church had turned against him was unfounded because Pearson was still minister in June 1878. However, Bennett's claims were partly true because the Pittsburgh Baptist Association threatened to withdraw support from the Fourth Avenue Church because of the church's 'whitewashing investigation' into Pearson's conduct.[62] The Fourth Avenue Church continued to support Pearson even after the Pittsburgh Baptist Association voted to withdraw its support by 51 votes to 10. Although the Association could withdraw its support, it did not have the power to remove a minister because that was down to the individual congregations.[63] As the Association considered Pearson's behaviour, the scandal deepened. In the middle of June, Pearson was arrested, along with the Rev. G. J. Brensinger, a former Baptist missionary in Pennsylvania, on conspiracy to defraud and cheat. The allegation was that they were partners with Rev. John P. Jones, a Baptist pastor, in a forgery. Jones was arrested in New York when he tried to escape back to Wales. Brensinger and Pearson claimed that Jones had implicated them but Brensinger was jailed before the trial whereas Pearson was able to put up bail of $1000.[64] The outcome of the trial is unknown but it must have added to the pressure on Pearson. Despite the continuing support of his congregation Pearson announced he would leave his pastorate in the autumn.[65] In January 1879 he preached his final sermon at the Fourth Avenue Baptist Church then left.[66] Yet again, Pearson's personal failings had thwarted his ambitions and destroyed his status as a respected non-conformist minister, but, as from his beginnings in Blackburn, his followers continued to support him despite his personal failings.

After Pearson announced his intention to resign, he returned to Blackburn for a short visit, during which time he gave lectures on his experiences in the United States. If Pearson thought Blackburn would offer a refuge from the scandals pursuing him in the United States, he was wrong. While the Blackburn Standard gave a straight account of his lecture in Darwen, the Blackburn Times ignored Pearson's lectures and, instead, gave an account of his life since leaving Blackburn in 1865.[67] The report covered Pearson's time as a lawyer in Massachusetts, his joining the Baptists, first as a lay preacher then as a minister and then finished with a brief summary of the scandal in Pittsburgh. The Blackburn Times claimed that two or three pamphlets published in Pittsburgh about Pearson had been sent to Blackburn. Pearson had crossed the Atlantic but his reputation in the United States had preceded him.

After returning to Pittsburgh to preach his farewell sermon, Pearson headed west to begin a new life in California. As Pearson had discovered during his trip to Blackburn, his reputation preceded him when he moved to California. Rev. Dr. Fulton of Brooklyn gave Pearson letters of recommendation but the New York Herald reported that an unidentified Baptist paper thought this was bad and then asked the question 'what have the brethren done to merit this affliction?'[68] Denied the opportunity to continue as a Baptist minister, Pearson returned to the legal profession. In February 1879 Pearson was admitted to practice law in San Francisco on the license he had obtained in Massachusetts in 1867.[69] After less than a year as a Californian attorney, Pearson became involved in yet another scandal but, although 'disreputable acts' were cited, these were not to cause Pearson's downfall.[70] In January 1880 proceeding began against Pearson for 'conduct and practice unbecoming a member of the bar'.[71] The case against Pearson was that he had knowingly falsified records in a divorce case. Pearson was employed by Mrs Eliza Burridge to divorce her husband. The law required that 'the husband should have neglected to provide for his wife the common necessities of life for more than one year'. The marriage took place on 2 September 1877 but Pearson changed the date to 2 September 1878. Pearson was struck from the rolls of attorneys and deprived the right to practice as an attorney or counsellor in the courts of California in June 1880. Pearson failed to answer the accusations.[72] The reason why Pearson failed to attend was that he left San Francisco to stay with his brother, and his family, and his mother in Slaterville in North Smithfield, Rhode Island.[73] Another place, another scandal, this time because of what could be viewed as Pearson's arrogant belief that no one would find that he had falsified evidence. Maybe like when scandal brought down Pearson in Blackburn, he fled to solace with his family.

Pearson's Final Decade: Preaching, Temperance and Prohibition

California marked the end of Pearson's attempt to find success through practising law. Being barred by the Californian legal authorities appeared to be the end of Pearson and scandal being almost synonymous. According to a report in New York's The Sun from March 1880 Pearson had given up on the legal profession and returned to preaching.[74] No definite evidence of Pearson has been found between his visit to Rhode Island in 1880 and spring 1885 when Pearson was advertised as preaching at the Baptist Church of the Pilgrim in San Francisco in May 1885.[75] When Pearson re-emerged it is probable that Pearson and his wife had been established in San Francisco for some time because both held important positions in the temperance movement by the end of 1885. In October 1885 Pearson was an officer of the Golden Rule Division of the Sons of Temperance while Mrs Pearson was the Lady Patriarch of the New Era Division.[76] Mrs Pearson was also the President of the Women's Christian Temperance Association in San Francisco.[77] In April 1886 Pearson was elected the important position of the Grand Worthy Patriarch of the Grand Division of the Sons of Temperance in California.[78] His reputation as a drunkard appeared to be well behind him and Pearson, and his wife, were respected citizens far from Pearson's working class background.

No evidence of Pearson having a church or congregation exists but he appeared to be a respected preacher, lecturer and campaigner for temperance and prohibition of the sale of alcohol in San Francisco and beyond.[79] In 1886 both Pearson and his wife moved into politics. Pearson acted as secretary of the County Central Commission of the Prohibition Party and both were chosen members of the new county committee and as delegates to the Prohibition Party convention in Sacramento in May 1886.[80] At that convention Pearson was elected as a member of the State Central Committee for the Fourth Congressional District in California.[81] After his term as Grand Worthy Patriarch, Pearson was elected as a delegate for Oakland to the Nation Division of the Sons of Temperance in Boston in July 1887.[82] Pearson had a role not only at state level but also at national level. Having achieved positions of such status and responsibility, Pearson's life changed again but, this time, the whiff of scandal seemed far away.

At the beginning of 1888 Pearson travelled with his wife to Arizona for the sake of her health. During their visit Pearson was invited to preach and to give lectures. As he had done from his brief time in London in 1861, he impressed, attracting large audiences. The Arizona Weekly Citizen described Pearson as 'a most eloquent and entertaining speaker'.[83] How long the Pearsons' trip to Arizona lasted is not known but by August 1888 they had moved to Phoenix, with Pearson becoming the pastor of Trinity Episcopalian Church.[84] How Pearson, a Baptist minister, became an Episcopalian minister is unclear but church administration was probably in flux in Arizona as the Bishop of Arizona and New Mexico, Rev. John Mills Kendrick, died in March 1888 and the new bishop, Rev. John Mills Kendrick, did not arrive in Arizona until February 1889. It is probable that the Phoenix Episcopalians were so impressed with Pearson's preaching that they offered him the church even though Pearson had not been ordained. Pearson was not ordained as an Episcopalian minister until after Bishop Kendrick's arrival in February 1889. Following a pattern in Pearson's life, soon he assumed other positions of responsibility, he was elected chaplain to the Arizona legislature and, shortly after his arrival, Bishop Kendrick appointed Pearson as chairman of the building committee for the new Grace Church in Tuscon.[85] Superficially, Pearson's new position in Arizona seems impressive but, on closer examination, it is not. In 1889 Arizona was a sparsely populated territory of the United States and the Episcopalian congregation small. In 1889 the church had only 459 communicants over ten missions in both Arizona and New Mexico.[86] During his short time in Arizona Pearson became well known but his position was not an improvement on his status as a respected Baptist preacher and promoter of temperance in San Francisco. Considering his previous career, doubts must remain about why Pearson left a prominent place in Los Angeles religious and political society for the frontiers of Arizona. Pearson's motive could have been purely altruistic, his concern for his wife's health.

Pearson's career ended in Arizona because, during a holiday in Los Angeles, he died on 29 September 1890 after suffering 'a shock of paralysis'.[87] Pearson was buried at St Paul's church in San Pedro, near Los Angeles. At his funeral he was remembered as 'a man of brilliant intellect' and some of his former parishioners from the Fourth Avenue Baptist Church in Pittsburgh who lived in Los Angeles 'esteeme[ed] him as one of the most gifted preachers and pastors'.[88] At his death Pearson's misdemeanours had been forgotten or, maybe, his former parishioners were some of those who continued to follow him despite his faults.

Conclusion

By the end of his life, Pearson succeeded in escaping his working-class beginnings in both Manchester and Blackburn to become an Episcopalian minister. Driven by ambition and with a talent for preaching and an ability to impress with his intellect Pearson found supporters in Professor Scott from Owens College and Rev. Parker, the founder of Cavendish College, and impressed Congregationalist chapels in London and Liverpool. However, scandals involving bogus doctorates and personal behaviour had destroyed his prospects with the nonconformist church in Britain. It seemed that Pearson's ability to court scandal would bring his downfall in the United States, too. Personal failings ruined his chances in the legal profession in Massachusetts and California. Allegations of sexual impropriety and drunkenness, similar to those that had driven Pearson from Blackburn, forced him to resign as Baptist minister in Pittsburgh, even though his mission had been so successful that a new, bigger church was needed. Even when the Pittsburgh Baptist Association turned against him most of his congregation continued to support Pearson, providing evidence of another of Pearson's talents: the ability to attract loyal followers who would disregard his failings. However, for 20 years those failings undermined Pearson's ambitions but he continued to strive with dogged determination. Then, for the last 5 years of his life, Pearson's charisma, preaching ability and apparent intellect gained him respect as a Baptist preacher and temperance campaigner in San Francisco and then as an Episcopalian minister in Arizona. If Pearson had died in 1880 he could have been considered 'a bad egg', someone whose life was defined by his character flaws, but, by the end of his life, he appeared to control these flaws to become a respected citizen. Through ambition, Pearson did escape his working-class roots to die an Episcopalian minister in Arizona on the frontier of the United States. Whether the young Pearson would have considered this a fulfilment of his ambitions is another matter.

Researched and written by David Hughes, June 2018.

References

[1] Blackburn Central Library, H2/66, Rev. R. W. Pearson: To the Independent Congregation of Bolton Station Meeting House.

[2] Birth record accessed using FreeBMD, http://www.freebmd.org.uk/.

[3] Blackburn Standard, 3 January 1838.

[4] 1851 England, Wales and Scotland Census, accessed using www.findmypast.co.uk [All census data used was accessed using Findmypast]

[5] In 1841 Robert's occupation was manufacturer, 1851 warper and 1861 pattern-maker.

[6] Parish Register of St. John, Manchester, 7 October 1861, accessed using www.findmypast.co.uk.

[7] Preston Herald, 20 February 1864 and 14 May 1864.

[8] 1841, 1851, 1861 and 1871 Census.

[9] John K. Walton, Lancashire: A Social History (Manchester, 1987), p. 110.

[10] 1841 Census, and birth record accessed using FreeBMD, http://www.freebmd.org.uk/.

[11] 1851 Census.

[12] In 1880 Owens College would become a constituent college of the Victoria University of Manchester and in 2004 would form part of the University of Manchester.

[13] Owens College was a failing institution when Pearson became a student in 1856. During his first academic year 154 students attended. However, only 33 were full-time students with the remainder being 33 schoolmasters receiving further education and 88 students who attended evening classes. By the time Pearson left in June 1860 the number of full-time students had increased to 57. Despite the struggle to attract students the staff and trustees rejected the idea of providing a practical education that would have suited the demands of local manufacturers and merchants: Joseph Thompson, The Owens College: its foundation and growth; and its connection with the Victoria University of Manchester (Manchester, 1886), pp. 138, 141, 153-4.

[14] J. Philip, 'Scott, Alexander John (Sandy) (1805-1866), Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Oxford, 2004).

[15] George Whitefield (1714-70) was a founder of Methodism with John and Charles Wesley.

[16] R. Tudur Jones, 'Parker, Joseph (1830-1902)', Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Oxford, 2004). Parker moved back to London in 1869 and in 1876 became the minister at the City Temple in London, which became an important centre of Nonconformism in London. He was a prolific author and was considered to be a communicator of genius.

[17] R. R. Turner, 'Cavendish Theological College, 1860-63', Transactions of the Congregational Historical Society, Vol.21 (1971-2), pp. 94-101.

[18] The City Press, 16 and 23 March, 20 and 27 April, 4 and 11 May, 1861.

[19] Aberdeen Press and Journal, 19 June 1861, Chester Chronicle, 22 June 1861.

[20] The Watchman and Wesleyan Advertiser gave a full account of the Pearson scandal, drawn from the thrice-weekly London newspaper, The Patriot, in December 1861 and January 1862, including Pearson being considered as the minister at Great George Street Chapel. The 1851 Census, taken on Sunday, 7 April 1861, captured Pearson visiting Liverpool as a guest of James Howell, a cotton broker and prominent Liverpool Congregationalist. Pearson's qualifications were recorded as Ph.D. and M.D. and, mysteriously, his place of birth as Clifton in Gloucestershire.

[21] Liverpool Mercury, 25 November 1861.

[22] Liverpool Daily Post, 4 November 1861. Christian David Ginsburg was born in Warsaw, Poland and was converted from Judaism to Christianity after which he moved to England, becoming a missionary in Liverpool where he became an active member of the Literary and Philosophical Society and had his first book published in 1857: Fred N. Rainer, 'Ginsburg, Christian David (1821-1914)', Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Oxford, 2008).

[23] Liverpool Mercury, 6 November 1861.

[24] The Watchman and Wesleyan Advertiser, 4 December 1861, reprinted a letter published in the British Standard that stated Pearson had bought the diplomas 'before he was of age' as Pearson was born in the last quarter of 1838, he turned 21 in the last quarter of 1859.

[25] Liverpool Mercury, 25 November 1861.

[26] The Watchman and Wesleyan Advertiser, 4 December 1861.

[27] Liverpool Daily Post, 29 November 1861.

[28] Blackburn Standard, 13 November 1861.

[29] Liverpool Mercury, 25 November 1861.

[30] Blackburn Standard, 18 December 1861.

[31] Undated report from the Patriot reprinted in The Watchman and Wesleyan Advertiser, 8 January 1862.

[32] Blackburn Standard, 16 April 1862.

[33] Pearson was included among the Reverends on the platform of a meeting at Blackburn Town Hall to welcome relief ships for America and to pass anti-slavery resolutions in relation to the American Civil War in a report in the Blackburn Standard, 25 March 1863.

[34] Blackburn Standard, 28 October 1863; Blackburn Times, 31 October 1863.

[35] Blackburn Standard, 27 May 1863; Manchester Courier, 30 May 1863.

[36] Blackburn Times, 26 December 1863.

[37] According to Abram, Montague Street Congregational Church did not open until February 1866: W. Alexander Abram, A Century of Independency in Blackburn: 1778-1878 (Blackburn, 1878), p. 54; allegations of financial mismanagement, which emerged during a trial in which a former treasurer of the Build Sub-committee sued the current Treasure in July 1864, may offer a further explanation of the delay: Blackburn Standard, 27 July 1864.

[38] Blackburn Times, 30 August and 20 September 1862; Blackburn Standard, 27 May 1863; Blackburn Times, 14 November 1863.

[39] Blackburn Central Library, H2/60, Rev. R. W. Pearson.

[40] 1871 Census.

[41] Preston Herald, 17 December 1864.

[42] Alexander Bruce Denniston Sword was born in Manchester in 1841 and in the 1881 census was recorded as a solicitor in Stoke on Trent.

[43] Blackburn Times, 26 August 1864.

[44] Blackburn Times, 10 September 1864.

[45] Blackburn Times, 1 October 1864.

[46] Blackburn Times, 8 October 1864.

[47] Preston Herald, 17 December 1864.

[48] Benjamin Nightingale, Lancashire Nonconformity, or, Sketches, Historical & Descriptive, of the Congregational and Old Presbyterian Churches in the County, Vo. 2 (Manchester 1890), p. 99.

[49] England and Wales Marriages 1837-2005 accessed through Findmypast. From the baptism records for the mid 1830s on Findmypast, it is probable that Sarah Ann Dunkerley was born in Greater Manchester. Why Pearson married in South Wales is a mystery but, as his mother's maiden name was Williams, he may have taken flight to his mother's family after being driven from Blackburn.

[50] London Gazette, 23 May 1865.

[51] London Gazette, 20 June 1865: Pearson's examination and application for discharge was in Lancaster on 14 July.

[52] Blackburn Standard, 15 November 1865.

[53] Liverpool Mercury, 4 November 1865.

[54] Pearson became a naturalized citizen of the United States of America on 22 November 1865: California Voters' Register, 1886, accessed through www.ancestry.co.uk.

[55] Address before the Essex Bar Association, December 8 1885 (Salem, Massachusetts, 1885), p. 58; The Essex County Directory (Boston, 1869), p. 233.

[56] The Essex County Directory (Boston, 1870), p. 29; The Essex County Directory (Boston, 1871), p. 273.

[57] Franklin College, 1834-1884: First Half Century (Cincinnati, 1884), pp. 42-47.

[58] Circulars of Information of the Bureau of Education, No. 5 (Washington, 1873), p. 80.

[59] Indianapolis Journal, 16 July 1873.

[60] Thomas Cushing, History of Allegheny County, Pennsylvania etc. (Chicago, 1889), p. 371.

[61] Rev. G. H. Humphrey and D. M. Bennett, Christianity and Infidelity; or the Humphrey-Bennett Discussion (New York, 1877), pp. 288, 295.

[62] Wheeling Daily Register (Wheeling, West Virginia), 6 June 1878.

[63] Chicago Tribune, 30 June 1878.

[64] The Evening Star (Washington D. C.), 20 June 1878.

[65] Chicago Daily Tribune, 18 August 1878.

[66] Cincinnati Daily Star, 6 January 1879.

[67] Blackburn Standard, 14 September 1878; Blackburn Times, 14 September 1878.

[68] New York Herald, 16 March 1879.

[69] Daily Evening Bulletin (San Francisco), 6 February 1879.

[70] Daily Evening Bulletin, 10 June 1880.

[71] Daily Alta California, 30 January 1880.

[72] Daily Evening Bulletin, 10 June 1880.

[73] United States Census 1880, accessed using www.findmypast.com: the census was taken on 11 June 1880. Pearson's brother, William, his wife, Catherine, their two eldest children, Lillian and Robert, and his mother, Mercy, all worked in cotton mills. Lillian's age was recorded as 15 and her place of birth given as England while her younger brother, Robert, was born in the United States making it possible that the William Pearson and his family emigrated with their brother but, as no record of Lillian Pearson being born in Britain has been found, which casts doubt on the accuracy of the census data.

[74] The Sun, 7 March 1880.

[75] Daily Evening Bulletin (San Francisco), 9 May 1885.

[76] Daily Alta California, 25 October 1885. The Order of the Sons of Temperance was a mutual society that assisted its members in leading a temperate life and, through defined contributions, provided assistance when members were sick; the Worthy Patriarch was the equivalent to the elected chair of a Division: Constitution and Revised Rules of the Sons of Temperance (Halifax, Nova Scotia, 1852), pp. 3, 5.

[77] Daily Alta California, 3 December 1885. More correctly, the Woman's Christian Temperance association was formed in 1874 with the Californian branch established in 1879; it became a national, campaigning temperance organization with foundations in evangelical Christianity: A Brief History of the Woman's Christian Temperance Union (Evanston, Illinois, 1907), pp. 9, 21, 28.

[78] Daily Evening Bulletin, 9 May 1885.

[79] See lecture given at the Silver Star Hall, San Francisco: Daily Alta California, 18 January 1886.

[80] Daily Alta California, 2 May 1886.

[81] Sacramento Daily Union, 13 May 1886.

[82] Sacramento Daily Union, 2 May 1887.

[83] Arizona Weekly Citizen (Tucson), 14 January 1888.

[84] Voters' Register for Maricopa County, Arizona, accessed through www.ancestry.co.uk: Pearson registered to vote on 25 September 1888; Arizona Weekly Citizen, 8 December 1888, reported that Pearson as being in charge of the congregation at Trinity Church, Phoenix.

[85] Tombstone Daily Prospector, 9 February 1889; Arizona Episcopalian, Vo.l. 9 No. 1 (Winter, 2018), p. 20: mistakenly, the author of this article gives the date of Bishop Kendrick's arrival as February 1888.

[86] University of the South, Series B No. 53, Calendar 1888-90 (Swanee, Tennessee, 1889).

[87] Los Angeles Times, 8 September 1890; Los Angeles Herald, 1 October 1890.

[88] Los Angeles Herald, 5 October 1890.

back to top