A number of records exist to show a use of brick later in the eighteenth century. The Blackburn Girls Charity School in Thunder Alley (now Town Hall Street) is described as being founded in 1763 and built of plain brick [9]. The Independent Chapel (1777) after which Chapel Street is named was the first of several nonconformist chapels of brick construction [10]. The Anglicans however appear to have stayed with stone!

Mike Rothwell draws attention to brick housing in the King Street and St. John's areas predating 1800 [11], and to a terrace of brick houses at Redlam used by handloom weavers [12].

Early bricks were generally long, thin and of no standard dimensions, each maker suiting himself. For this reason, an Act of 1776 established a standard of 8.5" x 2.5". Then in 1784 a Brick Tax was introduced, and this was to limit the development of the industry.

The history of the Brick Tax is amusing, and an object lesson to economists. It was levied firstly upon the number of bricks used. To counter this the size of bricks increased, commonly to 10" x 5"x 3". In 1803 the rate of tax on bricks of this size was raised, so makers switched to 9.5" x 4.5" x 3", just within the lower rate. Thus, brick sizes can be used to estimate the dates of some properties [13]. Historians should also note the type of bonding, and the adoption of tax-avoiding materials. Building stone was untaxed, leading to its increased share of the market. Builders also utilised external plaster, stucco and brick-like 'mathematical tiles', all untaxed. The tax was abolished in 1851. Since that date brick sizes have become gradually more uniform, rising four courses to the foot in the south, four to thirteen inches in the north.

One of the earliest industrial buildings of the area was brick-built, the old Pothouse on Haslingden Road [14]. This unsightly domed structure was built early last century and was to fire coarse pottery. Brick was used because of its ability to withstand high temperatures. The use of fire clay bricks for retorts, kilns and chimneys was a significant part of the early industry.

At least two early mills were brick-built. The riverside spinning mill at Whalley Banks is still standing, but Commercial Mill, Nova Scotia, was destroyed by fire. The latter, built in 1837, was known locally as "t'Brick Factory" [15].

The casual visitor may gain an impression that much of Blackburn's early terraced housing is stone built. However closer inspection reveals many such stone-fronted rows with brick sides and rears. My own home (1875), apparently all stone, in fact has brick chimneys and internal walls. Presumably the builders compromised between a customer's presumed preference for stone and the economies of brick construction.

Early brickmakers would establish a small temporary kiln close to a source of suitable clay and within reach of the targeted building site. Suitable clays of morainic origin are found around Livesey (where the use of brick appears to have been established at an early date) and Rishton. Certain individuals and families gained experience in the trade and were able to gain contracts from local builders - sometimes simultaneously!

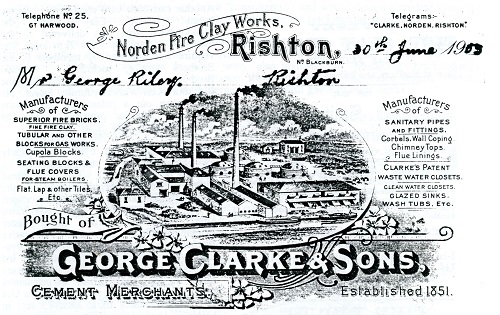

One such was George Clarke, a Buckinghamshire maker who moved to Lancashire during the 1840s and worked on Whalley Viaduct. The Blackburn Clitheroe and North-West Junction Railway gained its Act in July 1846. The Engineer resolved to use brick in constructing the viaduct needed to span the valley at Whalley. Over seven million bricks were utilised, and their supply was (at least in part) the task of George Clarke. Clarke dug clay locally and established a temporary brickyard for the purpose. The line opened on 22nd June 1850, and the next year Clarke opened a permanent brickworks at Norden near Rishton alongside the Leeds and Liverpool Canal. [18]

Bricks were identified as being a possible cargo from the time of conception of the canal. A toll of 1/2d per ton per mile was established by its authorising act of 1770 [18]. Whilst this trade never formed a major source of traffic to the canal company, the carriage of bricks to canalside customers as well as delivery of coal for the kilns was an important asset to would-be brickmakers.

Clarke obtained his supplies of clay from nearby collieries, and quarried brickshale in the Rishton and Cunliffe area. In addition to brick, he marketed pipes, chimney pots and W.C's. In 1861 he joined forces with a sextet of Bacup men to build the prestigious Rishton Victoria Cotton Mill beside the canal [19]. Both the mill and its associated housing were- naturally- of brick. Brickmaking survived at Norden until the 1960s.

Nearby, Levi Fish was producing bricks at Cunliffe. He utilised some of these to build himself a public house - the Cemetery (now the Lidgett Inn) at Rishton. Fish later opened a brickworks at Whalley.

During the 1840s the Leeds & Liverpool Canal Company suffered from severe competition from the new railways. They sued for peace with a consortium of railway operators, agreeing to lease to the latter (for a fixed sum and term) all tolls on merchandising traffic. Minerals Coals and Bricks were excluded [20]. The lease took effect in July 1850. One consequence was that independent carriers would seek cargos of bricks etc. other cargos being denied to them. Thus canal-side works gained from new markets and cheaper transport, they no longer had to establish near to the customer base.

Earlier, around 1800, Henry Petre of Dunkenhalgh, Lord of Rishton, had established a coal mine at Sidebeet, above the then intended line of the canal. In 1843 a John Swarbrick established a brickworks there and took over the now exhausted mines to extract fireclay [21]. A tramway was built linking the mine shaft, brickworks and quay. The company also established a canalside warehouse on Dock Street, Blackburn. However, Swarbrick was bankrupted in 1881 and the works closed.

Another canalside yard opened at Livesey around 1845. Clay from the Meadowhead area was delivered to the works by a tramway some 2km long. The venture was operated by members of the Brothers family, including Orlando Brothers, who was Engineer to the Blackburn Gas Works in Jubilee Street. It closed in 1894.

Blackburn introduced bye-laws as early as 1855 to limit the nuisance caused by "Brick Burning" [23]. The widespread disregard for these regulations led to the borough undertaking several prosecutions in 1877 [24]. These were withdrawn after intervention from the "Master Brickmakers" and "Operative Brickmakers", but from that time the bye-laws were more strictly enforced. This led to makers switching from small temporary kilns to the construction of permanent works. From 1884 the rules required a kiln to have a chimney of at least 75 feet in height [25].

Mike Rothwell details the brickworks of the late 19th and the 20th centuries [26]. These were mostly in the Livesey / Mill Hill area and later at Audley, and most were away from the canal. One notable works was at Whitebirk. It opened adjacent to Whitebirk Colliery, using clay from the pit to produce glazed bricks. It continued to operate for several years after the pit closed, relying for both clay and coal for the kiln on an overhead conveyor, an aerial flight of sixty buckets hung from an endless chain which was driven by a stationery engine. This system carried supplies all the way from the heights above Belthorn.

Probably the greatest influence on the brickmaking industry of East Lancashire was the firm of Whittakers of Accrington. In 1875, Grimshaw Park Brickworks was taken over by members of the Matthews family, described as "sanitary pipe makers of Runcorn". They installed a couple of brickmaking machines which had been developed by James Matthews. The patentee looked around for a partner to exploit the development, and made an agreement with Christopher Whittaker & Co. who operated a mill-wright and engineering business at Midge Hall Mill, Accrington.

Production and sales were buoyant, so that the works required extending in 1880. Whittakers benefited from the expansion in demand for bricks created by the growth of surrounding towns, the prosperous economy and declining brick prices. They established a role for themselves as brick "consultants", and would design complete systems and works, from tramways to kilns, as well as supplying brickmaking machinery.

William, a member of the Matthews family took over the Brow Brickworks in Blackburn, installing the new machinery in 1877. Another Matthews ran Baxenden Works. Blackburn Engineers, Clayton Goodfellow & Co. were also involved in producing brickmaking equipment during the 1920s with assistance from Whittakers.

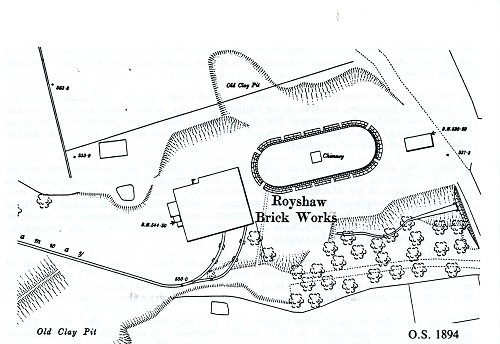

Meanwhile the Matthews were seeking to widen their brickmaking interests. Their venture at Waterfall was short-lived but more successful was William's enterprise at Royshaw. The Royshaw Brickworks opened in 1877 (incidentally the same year as Accrington, producers of the famous "Nori" Engineering Brick). This was the last new permanent brickworks to open in the borough, yes it was only a few yards from the brickfields of 1739.

William Matthews established his works at Royshaw Clough and built a "Hoffman" type kiln near the bridge. Kilns of this design were introduced from Austria a few decades earlier. The kiln was rectangular in shape, divided into (in this case) twelve chambers. Flues from each led into a central chimney which rose the regulation height to carry away the smoke and fumes. Each chamber in turn was fuelled and filled with machine cut blocks of clay which emerge as red brick.

Clay was extracted from the valley sides, and an elevated tramway carried it back to the shed for processing. The works pre-dated that part of St. James' Road, and in 1905 the land between the kilns and this new road, from which clay extraction was exhausted, became the site of Hollinshead Mill. The 1930s saw Hollinshead temporarily closed but brickmaking continued, by now under the control of a limited company, and with additions to the buildings. The Royshaw Brickworks Co. Ltd. was eventually absorbed by John Woods as Bog Heights, Darwen.

More land was obtained to extend the supplies of clay, but the onset of war limited development. By the 1950s the works had closed. Hollinshead Mill was later used by a car-parts supplier whose extension covered the demolished works; now only the exhausted claypits remain.

Most of Blackburn's Brickmakers closed around the same time. The last, Whittaker's Brow Brickworks survived until the mid 1960s. Now, twenty-five years later it is difficult to find much trace of the industry unless it be uneven ground at Audley or a name moulded into the bricks of some half-demolished wall.

Much of Blackburn still believes that brick is somehow "inferior", the poor relation. Stone-built terraces are listed, included in conservation zones, but equally meritorious brick structures are not. Surely, buildings such as the Old College at Blakey Moor show what can be achieved, and the bricks and brickmakers of Blackburn should at last receive the recognition they justly deserve.

References

[1] Sheppard Frere, Britannia p. 258-9.

[2] G M Trevelyan, English Social History p. 57.

[3] G M Trevelyan, ibid p. 78.

[4] J Bartlett, The Medieval Walls of Hull.

[5] G M Trevelyan, ibid p. 130.

[6] The National Trust Guide.

[7] This map is in Blackburn Museum, and a copy in the Local History collection at Blackburn Central Library.

[8] Blackburn Central Library, Local History Collection. This map probably dates to the late 1700s.

[9] Mannex's Directory of Lancashire, 1854. p. 266.

[10] Ditto p. 263. The Chapel had a "portico supported by three tuscan columns".

[11] M Rothwell, Industrial Heritage of Blackburn, vol.II p.33; vol. I p. 11-12.

[12] M Rothwell, Ibid, vol. I p. 8.

[13] Pamela Cunningham, How old is your house? p. 148.

[14] Bits of Old Blackburn, 1889, Chapter 16.

[15] Miller, Blackburn Worthies, p. 113.

[16] Industrial Archaeology, Lancashire County Council.

[17] M Rothwell, Industrial Archaeology of Rishton, p.11.

[18] M Clarke, The Leeds and Liverpool Canal, p. 127.

[19] M Rothwell, Ibid.

[20] M Clarke, ibid, p. 183.

[21] M Rothwell, Industrial Heritage of Blackburn, vol II p. 11 and p. 33.

[22] M Rothwell, ibid. p. 11 and p. 33-34. Local OS maps and directories list other firms.

[23] Blackburn Borough Council, Minutes 10th November 1884.

[24] Blackburn Borough Sanitary Committee, Minutes 23rd August 1877.

[25] Blackburn Borough Council, Minutes 10th November 1884.

[26] M Rothwell, Industrial Heritage of Blackburn, vol II p. 11 and p. 33.

Transcribed by Shazia Kasim

Taken from The Blackburn Local History Society Journal 1992, Volume 2, Page 7.

Written by Arthur Fisher.