Foster Yates & Thom

Alan Duffy’s Story

FOREWORD

The following is an account of my personal experience of working for FYT from 1952 to 1960 based on my actual memories of my time spent working there. It is as accurate as my memory now at 86 allows. Compared with modern times and Health and Safety the working conditions were very different but we got by without too many major safety issues. It is a story of times gone by.

PREFACE

FOSTER YATES & THOM

This Company was established in 1826 and my career there and the overall experience of working there had an enormous and lifelong effect on my subsequent career. From the first time I approached it to attend for interview I was overwhelmed by the immensity of the place. Walking up a street and approaching the factory there was a huge painted sign up on the wall it said:-

Foster Yates & Thom Ltd,

Canal Foundry

Heavy Precision Engineers,

Millwrights and Boiler Makers

Est. 1826

Absit Invidia [Absent from envy]

Every day I worked there I passed that sign and I never failed to marvel that after over One Hundred and Twenty six years these three founders of the Company still had their names up on the wall. What an amazing thing that was to me. I wondered if one day I might have my name up on my factory wall for all to see. Little did I know then what would come later in my life in that regard?

INTERVIEW

I was still attending school when I was invited to go to Foster Yates and Thom for a job interview for the position of engineering apprentice. This company was world famous and had been established in the year 1826. Everyone in our town and towns surrounding Blackburn knew of FYT or “Fosters" as it tended to be called locally. My mother's brother, my uncle Charlie had a good job there as did my dad Jack who worked in the steel bar stores. I had to create a good impression with Mr Pheasey the works manager who was going to interview me. I was nervous because he was known to be strict and a bit fearsome but fair to according to my dad and my uncle Charlie.

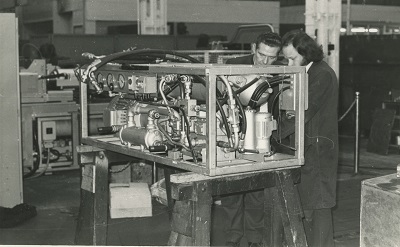

Charlie Lindow is the man on the left

When I arrived at the factory I was overwhelmed at the enormity of it. There were two main buildings one either side of Manner Sutton Street various noises emitted from the buildings. Bangs and clangs within a deep humming sound of what must have been machinery running. It all sounded very busy and exciting. There was an interesting smell around the place too. On the road just past the office entrance which was my destination. I noticed a horse and cart standing there the horse snuffling in a bag of food draped over its head the driver must have been inside the works. I learned later that this Shire horse was called Dolly and she and her driver were responsible for taking engineering parts from one factory to another. It seems it was cheaper than using Lorries. You will read about this pair later!

I opened the door with a little trepidation and introduced myself to the receptionist who was expecting me she asked me to sit down and someone would come and get me. Another boy came in whilst I was waiting he looked as nervous as I felt. Almost immediately someone came to show me to Mr Pheasey's secretary's office to await my turn for interview. She talked to me asking friendly questions and was very pretty and I soon felt relaxed. Mr Pheasey was the Works Manager. I later found out he was known as Mr Fosters. He had worked at the company for many years and ran most aspects of it and on engineering production matters there was nothing he didn't know and despite his tough approach everyone thought he was very fair and respected him immensely. As the saying goes “he ran a tight ship" I didn't realise at that moment that me a simple apprentice would cross his path many times in the future.

Very soon the secretary's phone buzzed and I was ushered into his office. He asked me to sit and asked why I wanted to be an engineer I replied “I want to be like my uncle Charlie" he said you will have to work hard to achieve. But we can give you every opportunity to do that. I then said I hoped to be a draughtsman. He told me I would have to go to Blackburn Technical College before that could happen and achieve the Ordinary National Certificate in engineering. He told me I would be given full day release including a night each week to educate myself to the level required. But when I reached the age of 18 I would have to attend at nights after work. He asked me if I wanted to be a craft apprentice or an indentured apprentice. I hadn't a clue what that meant. Craft is concentrating on a specific sphere of shop floor engineering e.g., operating machinery lathes, milling machines, borers, etc. or fitting machines together. Being indentured meant spending variable periods of time in all the departments so you gained a good spread of knowledge of everything the firm did. I opted for the latter thinking that having full engineering back ground would better help me if I became a draughtsman. Mr Pheasey said that was a good decision. I became relaxed and he asked me several more questions including what I did in my spare time. I told him swimming, football and music. Almost before I knew it the interview was over he stood up shook my hand and said we will let you know within a week.

My parents were eagerly waiting for the story when I returned home and were pleased for me. A few days after a letter arrived telling me I had got the job and I would start as Office Boy in the drawing office I would work there till Christmas then move on to the Blacksmiths shop .

I returned to my school Blakey Moor Boys School in the centre of the town to finish that period of my education. I enjoyed my time at this school and made many friends. After a family holiday with my parents to the Isle of Man. I left my childhood behind with no regrets and looked forward to an exciting future.

STARTING WORK FOR THE FIRST TIME

Two weeks later with my father I walked to work for the first time. It was a strange experience being admitted into adult life. I was a little nervous but very excited all at the same time. As we were nearing the factory we turned left into Quarry Street and there in a short distance was Canal Works, the home of Foster, Yates and Thom Ltd. As we got closer I saw the huge painted sign high up on the building.

We stood there for a few minutes to let what I was reading sink in, without really thinking I asked my dad if any of those peoples whose name was up there were still alive. Of course not, but their names are not forgotten after all this time! This moment has lived in my mind all my life. Then my dad gently gripped my arm and said “when you get in there my lad you will make mistakes. When you, do tell your boss, right away don’t ever try to cover it up. You never know how that mistake might affect others, always be honest. You might get a clip round the ear but you will always feel better getting it off your chest”.

DRAWING OFFICE

We entered the works and my dad pointed the way to the drawing office where I met a man called Jim Garwood who was the general engineering Chief Draughtsman. He shook my hand and took me into his office to get to know me a little. My duties would include looking after his draughtsmen in terms of tea and toast or any errands they may require. But my main job was to deliver blue print drawings to every part of the factory after I had most carefully recorded the drawings detailed into a leather bound ledger which I carried around the works. Visiting various offices or work places ensuring the recipient signed for them. It was a very important job really. Over the period I worked in this office I found out where everything and everyone was within the factory. I enjoyed it immensely and also slowly got to know the draughtsmen, bosses, secretaries and typists very well in this department. There were many characters amongst them and as time went on I had to learn the little jokes and tricks some of these people got up to, to embarrass me.

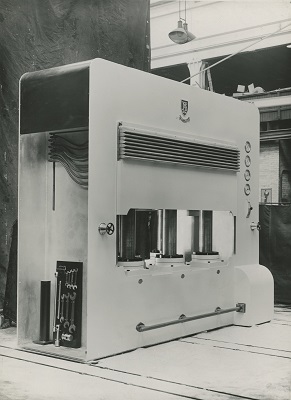

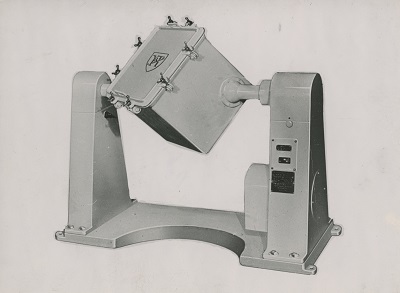

The main person in the management structure of the Drawing Office was the Chief Engineer. He was in total charge of the department, his name was Mr N.W. Louseley A.M.I.Mech.E, this title was the epitome of success as an engineer. (A qualification I achieved later) He looked a bit gruff and always dressed smartly with tweed three piece suit with gold watch and chain, but with me he was kind and grateful, when I went into his office every morning and afternoon with his silver tray of tea and biscuits he was always ready for a little chat. He had a large oak panelled office very nicely furnished and two secretaries whose office I had to go through to deliver his tray. I quickly decided that my ambition was to, one day, be a Chief Engineer. He became the man I looked up to and he created in me an ambition which at the time seemed unlikely to achieve. Immediately below him were three Chief Draughtsmen Jim Garwood already mentioned and Albert Wilkinson Chief Boiler Draughtsman. These people and their staff occupied a large main office. In a newer more modern office was the Press drawing office whose chief was Alan Worswick. The draughtsmen under his care were mostly younger men. Working on the design of new ultramodern types of machines called Lancastrian Hydraulic presses and Rotocube Dry Powder Mixers which in those days were hailed as the company’s future.

Traditional steam boilers and mill engines had gone out of fashion with electricity taking over. I didn’t realise at the time that the company was in the middle of a major shift in the type of engineering it carried out. These presses were the hoped for solution to the reducing business that the company was historically famous for.

In the main Drawing Office we had three typist’s one of these a lady called Doll Whitham she was blind from birth, and typed as well as any of her colleagues. She would listen to the person dictating the letter and typed this in Braille onto a continuous paper tape. On completion she would run her fingers along the tape and type in the usual manner. The finished letter was then returned to the writer’s desk for him to check and post. She made few if any mistakes. And always brought the letter back to the correct person. Years later when I was promoted to the drawing office she was still there and when I went to her to dictate my first letter. As soon as I spoke she said it’s you Alan you used to be our office boy. Amazing!

In this main drawing office were several men in their seventies the deputy Chief Draughtsman was Mr Herbert Dowell, he would show me drawings he had done in the past of Steam Operated Mill Engines. Some readers may have seen them in museums or old cotton mills. These drawings were so detailed as to be unbelievable, He later was awarded an O.B.E. for designing a huge wind tunnel for flight tests. His son worked at the next desk. Across the aisle were the Boiler Draughtsmen Mr Fallows, Mr Wilson and Mr Bowskill and several others in the office whose names I no longer remember. There was another elderly designer called Aubrey Boyd who seemed only interested in what he was drawing and sometimes I would stand by his drawing board and watch him work. One day I was stood there and he was working on a very complex drawing. As I moved forward to take a closer look I accidentally nudged his drawing board and small bottle of Indian ink, which was standing open at the top of the board, tipped over spilling black ink over a large part of his drawing. I was mortified when I saw the damage that I had caused. He just said “don’t worry lad it were an accident”. So many interesting people.

One place I had to frequent to do my job was to collect the newly printed drawings from the print room. In this small department were three employees. A photographer, an amiable Scots man called Mr Coughlin and his faithful assistant Miss Tulley plus the print man named Bill, he and I spent time talking about our beloved Blackburn Rovers when things were slack. The printed drawings were called Blue Prints because of their colour. A bright blue background and the actual drawing in white they always looked good to me, but speedier print processes were later evolved which made this process redundant.

Going up and down many steps every brew time was a bit arduous and I had noticed how hot the water in the wash basin taps in the Gents toilet were. I experimented with a spoon full of tea and produced what appeared to be a perfect brew so proceeded to fill up the various cups directly from the taps. I knew nothing about water systems and didn’t know that the hot tap water was never for drinking. I delivered what looked perfect cups of tea to my “customers” and got the shock of my life when to a man they spurted out the foul liquid. I quickly retrieved the cups ran down to the “works kettle” a monstrous device on the ground floor and brought back fresh cups to the relief of the drinkers. I never let on but learnt a lesson! The kettle I just referred to, was a huge gas fired water boiler which heated enough water to cater for all the hot drinks required for all the workers in the factory. All the shop labourers from every department wrestled with each other

approaching “brew time” to get first go when the water was at its hottest. The physically smaller labourers, “clients “were less fortunate. The kettle area was in a dark short tunnel between the fitting shop and the light machine shop, which also housed the toilets, it was a very dim and gloomy place. Lighting the boiler (done by hand) was a risky business and if the pilot light went out someone had to restart it. There must have been a technique to it that few understood. Whenever a novice to the procedure attempted it, everyone who knew what might happen and quickly left the scene, including myself. After a moment of hush and expectation there would be an almighty bang followed by a whoosh which went through the area displacing the caps of those not realising what was going to happen. Everyone in the factory heard the bang and an ironic cheer rang out from all the listeners!

Delivering drawings to all departments in the huge building brought me in touch with so many people and as time went on I became friends with some, and got to know most of the bosses. I was proud of myself doing what I considered to be an important job. One day I was on my way back to the drawing office via the heavy machine shop. Mr Pheasey was there supervising the lifting, by overhead crane, of a machining table probably around four tons from a large boring machine. One or two other men were about shouting instructions to the crane driver. I innocently proceeded to walk beneath the load being lifted. Feeling quite smug. Mr Pheasey quickly came up behind me, grabbed my shoulder pushing me away saying “never do that again you stupid lad” just as behind us there was an all mighty crash the load had slipped of the crane! Another important lesson learned!!

As I have said my job as office boy took me all over the factory and generally as I passed through different departments it was good to just stop sometimes and take in all the interesting things that were going on around me. There was just one department where I never stood around just looking. Not because it wasn’t interesting, but because it was the boiler making shop the noise levels in this department were off the scale. The clamour from numerous riveting and caulking tools was so loud it put me in a state of claustrophobia. Everything around me became blurred I was terrified. When entering the department I would stick my fingers in my ears and run through the shop to the foreman’s office were I would deposit the drawings and run back to the relative solitude of the other departments. One day I was caught doing this by the shop manager Mr Arthur Hulme, as I was passing he grabbed my arm stopping me in my tracks. He shouted “what dust tha think thar doin” I shouted back “because of the noise”. There on the floor was a huge boiler cylinder lying on its side, it was being riveted and caulked with about six men working on the job. The cylinder was about thirty feet long and ten feet diameter. Still holding firmly onto my arm he pulled me to one end of the cylinder and walked me very, slowly through from one end to the other. When we reappeared he said “that wernt as bad as tha thewt, wer it lad, tha did weel, tha shud be praad o this sel” Amazingly this experience cancelled out the fear of walking through this shop. From then on I would stroll casually through the place without a care in the world, stop for a shouted chat and showing interest in what these skilled men were doing. I never worked in this department but I bet it would have been an interesting experience.

It was coming up to Christmas when I would leave this office for another section of the company. I was given a small handmade card board box, it had a slot in the top and a slit in the side. Boldly printed on it was “Alan’s Christmas Collection”. The slots were indicated as for coins, the slits for notes (at that time I never seen a note, only five pound notes were available in those days and few people ever saw one) I was told in no uncertain tones that I would go round the two drawing offices and ask every employee to put money into my box. I said there was no way I could possibly do that it was like begging and my family was too proud for me to this. I was adamant but the pressure built when three young draughtsmen grabbed me lifted me up and said they would take me down to the typing pool, where several young women worked, there they would remove my trousers! They got their way and I did the collection. As I remember I did quite well.

There is however a little amusing story in connection with this. In those days everyone’s house had a gas supply and to keep the gas flowing, a meter was provided into which were fed penny coins to keep it flowing. It was not uncommon for a draughtsman to get change from the works cashier to make sure he had a penny handy. They often would give me a two shilling piece and ask me to go down to the cashier for change. Preceding my collection I didn’t realise that there seemed to be more requests for change than normal. I sussed it on collection day because I had more penny coins than I had ever seen!! My coat pockets were bulging and the weight was enormous and took a long time to count. Judging from what I received they obviously thought I had done a good job. Just a point. There were no notes!

CANAL WORKS

The layout of this vast factory might be of interest to some when reading my account of the time I spent in several departments but by no means all of them.

The Canal Works as it was called consisted of four buildings. The main two being the main works on Manner Sutton Street which stretched from Birley Street up to Eanem. The other two building were much smaller one on Fort Street stored miscellaneous engineering parts necessary for the assembly of machinery in the fitting shop. The fourth a more modern building referred to as the Godfrey Works was the main store for various steel bars, tubing and brass and phosphor bronze items used for Admiralty contracts. My dad was the store keeper in this department.

On the other side of Manner Sutton Street was the Fabrication Shop referred to as the fab shop. With Quarry Street on one side, this was a large very tall building in which welding and fabrication took place. It was formerly the main foundry where all the larger cast iron parts were made, all necessary for the construction of the huge steam engines in the main works in earlier days, which the company was World famous for. Also housed in this building was the laboratory for metal testing etc., there was also a very large annealing furnace in there to.

I never worked in this department.

Standing at the bottom of Manner Sutton Street with the main factory on your left, the first section of the building was the famous Boiler Shop it had a large access door opening on to Birley Street. Moving up the street the next section of the building housed the flue shop the workings of which I will expand upon later. Next up was the boiler out fitting department in which all the valves, piping and pipe fittings were stored for the installation of new boilers, or repairs, on site by crews of specialist engineers. This was a long narrow department. Next was the Light Machine Shop from outside the building it can be recognised by the large rounded top windows. This was a light and airy department with windows on the Birley Street side of the building. The next department still moving up the street through the tunnel referred to previously was the Fitting shop a totally enclosed work place where assembly and running and testing of new machinery was carried out. Just off this department on the Birley Street side of the building were the Smithy, the swarf (machine turnings) processing machine and the boiler house which provided the heating etc., for the works and offices. Next and last up the street was the huge Heavy Machine Shop. Off this at ground level were the tool room were cutting tools for the Light and Heavy machine shop machinery, also special precision parts were also made in there. The machine tool stores were in there too at the foot of a wooden staircase. This led up the joiners, maintenance and electrical workshops. These steps provided access to the press drawing office. The main offices were accessed from Manner Sutton Street some at ground level such as reception, Works Manager, planning office, progress office and time office. Upstairs were the usual other offices, personnel, buying, accounts, typing pool. The Managing Director and company secretary offices. Up another flight of stairs were the General and Boiler Drawing Offices, print room and works photographer.

Back to the story:

Three Lorries parked on Manner Sutten Street

The first Lorry carries a Rotocube, next is a Lancastrian Hydraulic Press

and finally a Lancashire Boiler

BLACKSMITHS SHOP

After Christmas I was moved into the Blacksmiths Shop known as the “Smithy” where I was to discover what it was like to be “turned into a man” In the Smithy worked five men. The room had a forge and anvil plus two steam operated sledge hammers. There was also an annealing furnace and an Avery Chain Testing Machine. More about all these items later. The five men mentioned were Rennie Broughton Chief Blacksmith, Tommy Forshaw his striker, Alf Heaton steam hammer operator, Edgar Nichols chain and block tester and Bill, whose surname I don’t recall, was a fitter. On the face of it they seemed a nice group of people and though nervous about what was going on around me, with fiery forge and steam hammer banging there seemed to be a lot happening. I was seconded to help Edgar and Bill with inspecting and testing chain lifting blocks and what was termed chain looking this was separate from the Smithy activities. I soon got into my stride wanting to do well and learn about this aspect of engineering. Edgar seemed quite old and Bill not much older than me. Outside companies like I.C.I. Imperial Chemical Industries and a host of others sent in their chains for checking and testing to meet Government standards. At first this job was interesting but looking at every link in every chain to see if there were any cracks or damage became one of the most boring jobs on earth, but once you had started checking the chain you just had to see it through to the end, and many chains were very long, some very heavy and very dirty. Chains from chemical factories were often covered in slime in various colours, you didn’t know what you were touching. Health and Safety was virtually invisible in those days.

Things progressed quietly for my first few weeks and I became relaxed about my situation there. But, and there is always a but, one day Rennie asked me to come over to the forge where he and Tommy were constructing an item out of steel strip. The forge was roaring, blasting out hot flames into which Rennie was holding the object in construction with huge grips. Tommy was standing by the anvil with his sledge hammer. Rennie manoeuvred the object then nodded his head and Tommy hit it (not his head just the object Rennie was holding) It was really interesting to watch what was going on and I could appreciate how skilful the pair of them were together. Rennie asked me to move in really close to him, he said to better see what he was doing. When they had finished Rennie reached to my side, apparently not looking and proceeded to rub his grubby sweaty hands into my hair instead of the bunch of cotton waste that was normally used. I was just at the age when boys like me were emerging into the Teddy Boy era. Trendy hair styles were becoming the rage and appearance in that area mattered. As can be imagined I was mortified that he would do this to me and reacted angrily. Without a word he and Tommy grabbed me, quickly turned me upside down and plunged my head into the cooling tank, (called in the shop, the Bosh tank). The water in the tank was rarely changed any liquid waste such as tea dregs and even urine when they were caught short, was thrown into the tank. It was a yellowish colour with a scum on it and smelt awful. Down to the shoulders I went with no care whether the liquid went into my mouth. I was placed back on my feet and try as I might my swinging blows failed to connect.

This was the first stage of being a man.

As time went on I did start to grow stronger and bigger but between the “learning periods” I was subjected to more and more episodes of becoming a man. Every few weeks a tipper lorry would reverse into the shop and deposit its load of coke into a compound prepared for it. On one occasion when I was busy with something else I was asked to climb in behind the lorry to make sure it wouldn’t damage anything. Without a thought I went into the compound and suddenly the lorry started tipping almost burying me in coke, apart from the dirty dust which was like a fog there were lots of cockroaches for some reason. It was disgusting I was filthy. Did I go to report these men to management or indeed my parents? No, I did not. It wasn’t what you did in those days.

This was stage two of becoming a man.

On another day they thought it fun to wrap me in small size chains around my arms and to lift me high off the ground and just leave me dangling I could feel the chain slipping every few minutes and I was scared almost to death. I didn’t shout or scream I just hung there until the ordeal was over I wouldn’t let them think they were in any way scaring me.

Stage three of being a man.

I noticed that Edgar didn’t take part in these trials but I remember going out of the factory on a job to test some lifting equipment in a small corn flour merchants in Peter Street in our town. It was exciting to be working out as they called it. The work shop we entered was not huge but it was constructed like a cotton mill with North Light roof. We got the ladder out and put it up alongside a chain block which was hanging on a beam. Edgar climbed up with a hand brush in his hand, there were several inches of corn dust on the beams above my head. With no hesitation other than to say “Hewd onta th ladder lad” He proceeded to brush off this dust for several minutes covering me from head to toe. I was coughing and spluttering for days. Edgar was quite amused. By the way, Edgar never ever called me Alan. To him for some reason I was Alanalio. Many years after leaving FYT I was walking in town and who should approach but Edgar looking resplendent in a tweed suit with yellow waist coat, bow tie, trilby and walking stick. He must have been really old then. I said” hello Edgar how are you? He stopped looked at me concerned he might be in danger. After what seemed minutes of scrutiny his face lit up and he said “Heee its Alanalio!” tipped his hat and walked on I never saw him again.

Stage four of becoming a man.

I was growing all the time in every respect but I still had two more “making a man of me” hurdles to cross each far worse and dangerous (for me).But of course didn’t realise it at the time

I mentioned earlier that in the department was an Avery Chain Testing Machine. This machine comprised of a metal vee shaped channel let in to the floor of the workshop. At one end was a moveable, slide mounted driving head, a bit like a lathe head stock but with a large hook mounted upon it. At the other end of the channel is a large fixed hook. The action of the machine is to place the chain to be tested into the channel and attach each end to the hooks referred to. The machine is set in motion and the driven end drives backwards until the chain to be tested is taut. At this point the specified test strength of the chain is entered into the machine. The puller then continues until it reaches the specified strength of the chain. In the event of the chain breaking in the process it being contained within the metal channel the chain was prevented from flying and hurting anyone present. I hope that’s clear so, “making a man test number five” started.

I was grabbed and lifted, it took most of them! They pushed me down into the channel, small chains were wrapped around my ankles, and my arms were pulled right back and another chain put round my wrists. The chains were mounted on to the hooks on each end of the machine, which was then started. The worry was about what would happen to me if for some reason the machine went wrong, and was stronger than these men just wanting to scare but not really hurt me. The experience was very unpleasant but apparently I had bruises on my ankles and wrists but no one at home noticed.

I had passed test five.

The final test number six involved the Annealing furnace previously mentioned.

This was a simple rectangular box shaped compartment about twelve feet long, three feet wide and six feet high. It was completely lined out with fire brick and was gas fired (coal gas then).The equipment was let into the floor and a trolley with wheels mounted upon rails so that the trolley once loaded can be winched into the furnace through a winch system. The steel metal components are placed on top of the trolley which has fire bricks forming a surface. The process being to normalise the component after it has been welded together. Welding can stress the component, but if it is heated to high temperature (red hot) and held ( known as soaking) at that temperature for a couple of days then allowed to cool back down the component is stress free and easier to work with after the process.

It was a typical day, many fabricated components and chains had built up to the stage when it was appropriate to fire up the furnace. The various items were gathered onto the trolley top. The various items piled on top of each other in a big stack then the trolley was ready to be winched into the furnace, a task I was pleased to undertake. I was nearing the end of my time in the smithy and had come to enjoy the camaraderie of my colleagues. I now felt that at last I was one of them and could give as much I could got. There was just Edgar, Bill and myself there. When the trolley was completely inside the furnace Edgar suddenly said to Bill “did tha hear that, summats dropped off at the back ot trolley” I heard not a thing but Bill told me crawl into the furnace and check. Gullible me, was in there like a flash wanting to help. The moment I was past, the furnace door, dropped into place from a cable system and entombed me inside in the darkness. I decided that this was obviously another prank and sat uncomfortably on the pile of components. I said nothing just sitting there. They will open the door soon, I thought when out of the blue, I heard Edgar say to Bill “wur needed int top shop”. There was silence for quite some time then I heard Rennie’s voice he was talking to Tommy and Alf. One of them said “look the furnace is closed it must be OK to fire it up” my heart went into over drive and I panicked. I shouted and kicked the furnace door hard but it seemed no one was listening. Then I heard the hissing sound that I thought was gas entering the furnace. I was shouting and trying not to breathe in what was a poisonous gas. I had never been as terrified in my young life as on that day as I waited for the whoosh of flame to consume me. Suddenly the door opened and there laughing merrily were all five of my comrades who thought it hilarious. The gas I heard was in fact fresh air which is fed into the furnace to increase the temperature of the furnace. I was never as angry as on that day. I attacked them swinging my fists in deep anger but these big men just brushed me off. This was my last test and for the remainder of my time in there I was treated as an equal. Years after when I had achieved my promotion to draughtsman and occasionally popped in to the Smithy. I was treated as someone special and they were convinced that they had played a significant part in my success. I can’t say that in engineering terms I learned a lot working in the Smithy but in part they did make a man of me. I faced many challenges in my later working life where on two occasions my decisions saved lives.

I will add a couple of comments about Tommy and Alf.

Tommy, was a dab hand at making a full English egg, sausage and bacon breakfast. He would warm up a shovel on the forge, pop eggs, bacon and the sausage on it and hey presto. Very quick and easy, we would take buttered slices of bread into work and enjoy the feast. After I had visited the dreaded works kettle to brew our tea of course.

In those days professional wrestling was popular and in the winter most weeks King Georges Hall would be packed. It was about two shillings to enter and Tommy worked there when there was a contest. I bought tickets for me and my best pal Bernard. Every time we went he would be sitting at the top of the stairs with a bucket between his legs. His job was to tear the ticket in half, deposit half in the bucket and half was given back to the customer. Without looking up he would feign ripping our tickets and returned them to us intact ready for the next occasion. They became quite worn after a few visits then we had to buy new ones.

Alf, was a very big man and very quiet I noticed he never took a “main” part in any of my “trials”. He operated a very big machine called a steam hammer which could deliver a blow of many tons. Some jobs needed heavier blows than a striker like Tommy could deliver. His control of the power of this machine was critical and believe it or not you could hold a normal hen egg with tongs between the face and the hammer and he could bring that hammer down very slowly and trap the egg with just enough force to hold but not break it. He won a few bets with staff who doubted his skill.

HEAVY MACHINE SHOP

My next step on my indentured journey was to the Heavy Machine Shop or the “top shop” as everyone called it. This department was awesome, all the machines were huge with a few being enormous. The man in charge was called Tom Greenwood he was always referred to as “Jappy” Maybe he looked a bit Japanese but that’s what everyone called him but not to his face. He was typical of Foremen in those days, there was little subtlety in their management styles. He could however as I soon found out, operate all of the machinery in the shop. In those days man management was achieved by using forceful language and trying to look tougher and intimidate the men they controlled. He had a charge hand to assist him called Bill Barber who was a much kinder type of man. These two men were responsible for the production of all the work carried out in this workshop. This part of the main building was at the top end of the factory closer to Eanam. At the other side of the factory wall was the Packet House pub whose customers largely worked at FYT it was very popular. It is now demolished.

The machinery used in this shop comprised of the following:-

Two plaining machines, one 8 feet wide the other 10 feet wide, they were used for machining the top side of a component, up to about 5 feet high and tables of 15 and 25 feet long respectively. The table would traverse to and fro under a cross beam which held the cutting tools. To each side of the table were other tool boxes for machining the sides of the component. Components could be huge, weighing several tons and occupying most of the table area. On occasion the table could accidentally over run and travel much further than was intended. There was a popular story of the corner of an over running table crashing into the outside wall and pushed bricks through into the pub next door. Spilling lots of pints? I had an amusing incident on the 10 foot machine and will cover it later in the text

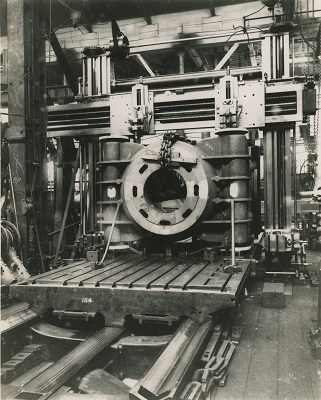

Heavy Machine Shop

The really big machine was a Face Plate Lathe with a chuck of 25 feet diameter. It was mounted on a huge headstock which bolted into the floor. A huge pit was created in the floor about 15 feet deep, the chuck’s centre line, level with the floor. All the swarf (metal turnings) dropped in to the pit where it built up over years and was emptied by an overhead crane with a magnet at the end of the chain. This immense chuck carried eight sets of gripping jaws. These held the component during the facing process. In front of the chuck was a moveable tool post which could traverse across the face of the component (usually ring shaped) The operator, believe it or not stood on 9 inch wide planks which partially cover the pit, whilst operating this machine. Mounting a component on to the chuck was a very dangerous process and required much skill from the operator and the crane driver. The reader may find it difficult to picture this machine. I was led to believe it was unique having been designed and built by FYT many, many, years ago.

I was told that this machine was specially built to manufacture ring shaped components for the Sau Paulo Railway in Brazil. A jig circa twenty feet diameter was always leaning on the wall near this machine. Whilst I was working for the company but not in this department, an order was received from the railway company for a thrust bearing made in phosphor bronze. This bearing was 16 feet diameter 10 inches thick and maybe 18 inches wide. The jig (a device specially designed and made to secure a particular component whilst being machined) was set up accurately within the chuck jaws, then the component was secured into the jig. Due to the rings size it was made in sections which were pre machined to enable them to be bolted together in the jig to form the ring.

Another big machine was for horizontal and vertical plaining and slotting. It consisted of a wall shaped cast iron structure with mounted machined slides horizontally and vertically with driven tool boxes. A large flat machined slotted table to enable securing the component with Tee bolts was precision mounted onto the floor. The wall was around 12 feet high and 15 feet long. I can’t recall what it was called. It was unique so maybe the company designed and built this too. It was only used occasionally and I recall that the company sold it when I was working elsewhere in the building.

There were also several horizontal boring machines of all sizes they are very versatile and can carry out many tasks. They can drill and bore holes in a component which is secured to a flat square shaped slotted table. These machines have a headstock fitted with a rotating chuck within which is machine slide onto which a tool holder can be mounted to face machine a component. The chuck can be raised and lowered and the table is moveable to and fro and side to side. An unbelievable selection of machining arrangements are possible with these machines which require very skilled operators. Several of the machines were of UK manufacture and Kearns a Manchester Engineering Company was the most popular supplier. But whilst I was in this shop the company bought a horizontal boring machine from Germany it was larger than the other borers and was a smart maroon and cream colour. The manufacturer was Droop & Rein and they also bought a large slotting machine from a company called I think called Walenbourg.

Another big machine was a 30 feet between centres lathe. It was quite high, and the operator stood on a platform attached to what is called the saddle which holds the cutting tool. This travels at a selected speed along the length of the lathe cutting the metal as it goes. The chuck accepted a component around 6 feet diameter. This machine was only used occasionally because another department was equipped with more modern machinery capable of doing similar jobs more efficiently. I will tell an unfortunate tale about this machine later in this text.

There were several other machines in this shop but were used only randomly and are not really worth a mention.

The shop worked regular days for the most part but one or two worked on a shift system which suited them for some reason. A man I think called Jonny Eyles worked on a smaller plainer for nights only. During my time in this shop I never worked on shifts.

Having set the scene I arrived in this shop at 7.30 am ready for a new and hopefully less threatening environment. I was greeted by Bill Barber a friend of my uncle Charlie. Who worked in this department and was well respected by his work mates and most people in the factory. He was what was called “a marker out” this probably the most skilful of all the jobs in the factory. As I have mentioned already FYT were precision engineers Charlies job was to put a component often a huge iron casting or a welded fabrication often weighing many tons onto a large iron precision ground table a little higher than a table we have at home. Once there he would make sure it was standing straight and level on the table. The component was at this stage not machined and had a rough finish but many parts of it needed to be machined to match the blue print drawing. The casting process and fabrication process are not very accurate so if a component was put straight onto a machine like above, the operator may find that when he machines one area then finds there isn’t enough metal to machine another part of the component. The only way for the machinist to know if it is safe to machine an area of the casting is to get Charlie to mark out exactly where the machining takes place.

By using many special hand tools, he had made himself over the years. Charlie with his assistant sets the component square to the table then using height gauges he checks the overall dimensions and with tape measures, spirit levels etc. he carefully manoeuvres the component until he can mark the places to be machined for the machinist to work to. All cutting areas are white washed and then lines are drawn showing were each cut is to finish. To ensure the lines are not rubbed out, using a small peening hammer and a centre punch he can make pop marks all along all the machining lines. This a very time consuming task which if not done right can cost the company thousands.

Largely because the machinery was so big it was not uncommon to see two men working on the set up of the machine. With jobs so large setting up could take days with the operator and his mate moving the component around on spacer plates of varying thickness working to the lines Charlie had marked previously. I cannot write in detail how these very skilled men achieved the appropriate settings to ensure the component could be safely and accurately machined. As an apprentice I was given into the care of an operator on a horizontal boring machine. Because this particular machine was delivered with its machine table missing, adjustments had to be made for the machine to carry out horizontal drilling and tapping of holes in an upright flat surface. (The story being, that this table had been lost at sea during the machines delivery from the USA during the war). My job was to be at the beck and call of the operator, going for brews, going for the drills and taps needed for the job we were doing but not really being taught anything at this stage. I think the idea was to get me used to the enormity of the machines we used and the size of the jobs we were carrying out. The thing was, once a component was set up for machining the actual cutting of the metal was just a case of keeping the operators eye on things. It didn’t need two of us for that, so once machining was in progress, Jappy would appear and take me over to another big machine to once again assist the operator in setting the machine with another component. I must admit seeing the skill of these men was amazing and many times special bolts, packers etc. needed to help the setup and these had to be produced by the operator. As time went on I became more of an active part in the proceedings and as I got older I found I could operate some of the smaller machines like lathes and milling machines and could really help.

I told the reader earlier about the bigger machines in this department and eventually I found myself working on that huge facing lathe over the pit. We had to machine a very big ring about 16 feet diameter weighing about six tons. It had been constructed in segments. Each section precision machined, to enable each segment to be connected together to form the ring. Standing upon nine inch wide wooden planks was very scary but when over a pit fifteen feet deep with lots of sharp metal turnings down there as well, I will leave it to your imagination it was terrifying!! Clamping the ring in the chuck jaws was a difficult job carried out whilst the crane was holding the weight of the ring and holding it back against the face plate at the same time. It was a two handed job and mine proved useful. I worked watching the operator all the time and waiting for instructions to pass a spanner, levelling plates or hammer etc. Whilst trying to forget the dangers from where you were standing. Eventually with the contributions of me, plus the crane driver, (a very skilled man himself). Then last but not least the operator of this mammoth machine we were ready to go. The chains holding the component were released and we are standing there on the planks hoping that the ring won’t drop off and take us all crashing down into the pit. Of course the “team” had made sure of that and machining could now commence. Standing close up in front of the rotating chuck as we needed to be, started to cause problems with dizziness, and took some getting used to you needed to be constantly aware of the potential dangers. Eventually it became possible to relax a little but sometimes unthinking you would step back just a little and your heel would drop over the edge of the plank and you got the feeling you were about to fall into the abyss! I would get settled then Jappy would return then after a chat with the operator he would take me away to help with the setup of another big machine with another operator. Setting up the machine properly was key to becoming a skilled operator. Just standing there watching the machine metal off a component taught you nothing at all.

I helped with scores of set ups on all types of machines and learnt a lot, then I sometimes went down to the light machine shop where there was a smaller horizontal borer to do small simpler jobs. This was all about getting the practical skills I would need to prepare me for becoming a skilled man. But there was still a long way to go. After about a year in the heavy machine shop, one day Jappy gathered his apprentices together (about four of us) and told us the engineers union, (The Amalgamated Engineering Union) was calling a one day strike the following week, we had heard about this and assumed we would get that day off. He soon crushed our hopes, telling us we would be in and running the machines. We couldn’t believe it! When the day came we clocked in and went up to the heavy machine shop where he awaited us. He gave us all a short lecture on his views about the strike which was unheard of in those days. Then he said I am not letting this day go to waste, so all of you will operate a machine for today. I must say we thought it must be a joke but this man didn’t really do jokes. He walked off with one lad who was much older than the rest and was soon back having made sure the young man could safely work the machine. Eventually it was my turn he gently pushed me forwards towards the ten feet wide plaining machine one of the biggest machines in the place the one that was famous for spilling every ones beer in the Packet House mentioned previously. It was also responsible for decapitating an operator several years earlier.

Already on the huge table of the machine was a very large cast iron gear box casting. It was probably fifteen feet long and eight feet wide probably weighing about seven tons

With a five feet high casing coming out of its centre. Because of this, the bridge carrying a slide on which were mounted the moveable cutting tool boxes, had to be kept high to prevent the component striking the bridge when passing to and fro underneath it. Because the machining process was to be carried out on a lower surface. A special tool holding bar had to be manufactured, this had to rigid and strong enough resist bending when the cutting tool connected with the surface to be machined. The holding bar was about six inches square section and protruded downwards to the component about eighteen inches below. Because of the temporary modification the depth of the cut had to be applied manually not automatically as was normal. Some tall step ladders were standing against the machines bridge with something that looked like a starting handle (as supplied with most cars in those days) lying on the top. “Up you get” Jappy said, indicating the step ladder, which on climbing it, I discovered was somewhat rickety. Soon I was in position. He climbed onto the machine table, which remember is twenty five feet long and ten feet wide. The controls of the machine were carried at the end of swing out cantilevered arm with a dangling control station comprising many buttons He confidently pushed a button and the table moved slowly forward, then grasping the edge of the component he bobbed down to see how far from the top face of the component the cutting tool was. It was too high to connect, the table travelling the full length of the component before returning to the start position a bit more quickly. He moved the table forward and stopped under the cutter which I then lowered to a position just touching the top surface. He traversed the table a couple of times then he told me to “put a cut on.” This was his catch phrase and pity the man operating any of “his” machines who did not put an adequate cut on from Jappy’s perspective. I was still standing on top of the ladder with my starting handle. I gave it a knock and the tool dug in and started to cut off metal, this started the slow process of machining the component. He went off in search of another apprentice to let loose on another of his machines. About an hour or so later I was sat on the top of the step ladder when he returned. I had stopped the machine awaiting further instructions and was feeling rather pleased with myself.

He decided then to remove more metal, so set the machine in motion following his next instruction to put a cut on, I tapped the starting handle but not hard enough it seemed, “get a cut on he said hit the bloody thing!” I tapped again but it was not enough for him. He then shouted with all his might repeating his previous instruction this time using Anglo Saxon phraseology. I hit the handle really hard and due to a soft spot in the mechanism the tool dropped down about two inches. He was in a stooping position eyeing the cutting tool as the leading edge of the component approached at cutting speed, a sequence of events started that I never could have imagined. As soon as the tool hit the component this huge machine shuddered, the hefty tool bar on which it was mounted started to bend backwards then with an almighty bang a large piece of the component broke off then the tool dug in and started cutting, this time chunks of the metal, now red hot, started pinging off in all directions but mostly where Jappy was standing. He was getting showered his face and clothes were taking the brunt of this red hot spray of metal. He then sprang back with the shock of it all and fell off the table which was two to three feet higher than the floor. I quickly dropped off my ladder and grabbed the control and hit the emergency stop. Everything went quiet and when I turned around he was just getting to his feet.

He looked very badly shaken he was rubbing his legs his suit was smouldering and his face looking like he had been attacked by wasps. He didn’t want my help or sympathy, he looked me straight in the eye and said the immortal words “I know I told you to put a cut on son, but that was f…ing ridiculous!” He didn’t shout at me or say it was my fault, he just said “don’t worry lad someone will sort out this mess tomorrow,” and that was that. From that point on I respected that man and to me he was Mr Greenwood.! It was the first time I had actually been in contact with him and looking back his loyalty to the company, in trying to keep his department operating during the strike was commendable. That’s why it’s still in my memory all these years later.

Earlier I mentioned a very large lathe.

On another day I was helping another operator set up a job on a boring machine when there was quite a stir in the department. Someone had been hurt and it was Mr Greenwood. It seems he was watching progress on the machining of a very large steel cylinder it had been rolled in the Boiler shop and had a welded seam along its length and it was about six feet in diameter. The operator on the machine was Bob Fisher and a star man, he was a quiet man and was always concentrating on what he was doing. He was setting up this cylinder to get it ready for machining along its length it was quite tricky because with it being a cylinder tightening the chuck jaws too tightly could deform the cylinder. The protruding weld also was problematical. Mr Greenwood had walked passed Bob as he was setting up his machine a few times and convinced himself things were not proceeding fast enough. He climbed up onto the platform on which the operator stood whilst the machine was in operation, pushed Bob to one side and apparently said he would set up the machine. The tricky bit was getting the cylinder to run true so that the thickness of the cylinder wall was not compromised when machined. Bob had almost completed the set up, he had a sturdy piece of wood fastened into the tool post and had inched it as close as he could get to achieve a satisfactory setting. It was at this point Greenwood took over he pushed the wood closer to the rotating cylinders outer surface forgetting the weld which was like a ridge along the cylinder surface.

He was concentrating so intensely that he didn’t see the welded seam approaching then it was too late his hand, was snatched into the gap pulling off three of his fingers. He jumped back but the damage was done when he turned round Bob fainted. Mr Greenwood stepped down from the machine looked at his hand and reportedly said “I’ve made a bugger of that! “He then walked unsteadily to the ambulance room for some medical attention. Someone picked up the fingers with a hand rag and followed the wounded foreman to the medical facility. Some Ghouls from other departments turned up to have a look at the gory scene. Mr Greenwood was back at work the day after, heavily bandaged, unfortunately his fingers could not be reattached. Once the bandages were removed he always kept his damaged hand in his pocket. He was certainly a tough guy was our Mr Greenwood.

It might be worth mentioning at this point that FYT were very concerned about the safety of their employees and had fully equipped medical facility including an operating theatre in case of serious injuries. There was a treatment room and the unit was manned by a senior nurse and junior nurse both women. They were there for small injuries which were very common and providing medicine for coughs, colds and sore throats. The facility was well used. A doctor came in one day a week too. The company also provided a security service too with men dressed just like policemen.

My time in the Heavy Machine Shop was coming to an end because of my indentured apprentice status. Work was drying up and there was some talk of temporary layoffs. Some of the bigger machines only ran for short periods with work for them coming in fits and starts. The powers that be suggested that these machines would be cleaned down with a view to painting. The apprentices were gathered together equipped with buckets, special cleaning fluid to clear off the accumulated oil and grease, hand brushes and rags. Another apprentice called Bob Draper who was a year younger than myself, were shown another large machine which I did not include in the list outlined earlier.

This machine was in fact one of my favourites. The technical description is Vertical Boring and Turning Machine. We, for some reason, called them Razzle’s the company had two, the one me and Bob were going to clean was the bigger one with an eight feet diameter chuck. It looked like an upside down lathe. The machine had four tool posts and could do two operations simultaneously. It stood about twelve feet high and above the chuck was a substantial cross rail on which were mounted two of the tool boxes. It was very versatile from our perspective it was a very big machine to clean. We needed step ladders and it seemed very exciting for us to be doing something different and it was an opportunity to get dirty, very dirty. For some reasons most apprentices enjoyed getting dirty. Fortunately for our mothers our boiler suits were supplied free by the company and we always had a clean one to put on when another was dirty.

On the machine chuck was a finish machined phosphor bronze gear casting about six feet diameter comprising about eight segments bolted together, it was waiting to be removed for delivery but left unclamped on the table to be removed later and was in no one’s way. Bob and I got ourselves organised determined to make this big machine clean and shiny. It took longer than expected and the task became boring but with Mr Greenwood’s encouragement we stuck at it. We had water and spirit cleaning fluid flowing all over the machine unaware that we might be creating any problems. About two weeks in to the job, one morning, the works internal transport, referred to much earlier in this story, appeared. A horse called Dolly and a large cart arrived with her driver. They had come to collect the gear segments that were still lying on the chuck of the machine. Mr Greenwood and the operator of this machine, plus a labourer lifted the segments by hand from the machine to the cart. The remaining pieces were too heavy and far away to be reached comfortably so the operator switched on the machine and took hold of the control box which like other systems on many of the machines was hanging on a cantilevered arm. Amongst the controls available is the “inch” button which when pressed rotates the chuck a few inches. His action created mayhem! Instead of inching the machine started to rotate very fast the four tool boxes sped to their extreme points and the remaining segments of the gear were flung off the chuck with great force. As I said earlier there were five humans and one horse standing there and not one of us were hit by these heavy pieces, two demolished the guards on the back of the machine another knocked a big chunk out of one of the tool posts the remaining two pieces went between us the land on the floor. Suddenly sparks were flying from the upper parts of the machine and from where the drive system was for the machine. There were crackling noises and lots of smoke before a big bang brought the machine to a standstill. We all looked at each other with shock and the thoughts, of what might have been, if fortune had not been on our side. A large crowd had suddenly appeared, it was another story for the history of the company. Dolly who was totally unperturbed by the incident went off with her cargo. An electrician appeared and within a few minutes of checking, declared that the machine needed a complete rewire and many new parts. The reason for the incident was letting two young apprentices clean the machine using too much fluid. Suffice to say Bob and I were not punished but others more senior were. The cleaning of the machines by apprentices was abandoned and lessons were learned.

Lancastrian Hydraulic Press

LIGHT MACHINE SHOP

I stayed at the Heavy Machine shop only a short while longer and was asked to move down to the Light Machine Shop where they were short of lathe operators. This was a work shop equipped with several centre lathes some medium sized, some large but not as in the heavy shop, there were milling machines. A honing machine which was unique and used for finishing the bores of hydraulic cylinders made on the longer lathes. There was the small horizontal boring machine which on occasion I had carried out some work. There were a few turret lathes used for making small parts in large numbers. The foreman of this shop was a man called Charlie Royle a thin man, who seemed always to be in a hurry who got the jobs done in the way other foremen did, a combination of harsh words and threats if things didn’t go the right way. After welcoming me he introduced me to his charge hand.

A lovely man called Dick Scholes, he came into my life again many years after I left FYT. He who would be my mentor for the whole time I worked in this department. Dick was a Salvation Army man very laid back, a pipe smoker and unlike so many employees he never ever swore. Sometimes he would come close, if I did something wrong on my machine he would come round to look see the problem. Then putting is hand on his forehead feigning anger he would say Fan my brow!! After few minutes the problem was solved, he was very skilled and knew all the tricks of the trade to correct the mistakes, I like others occasionally made. Once he had done his magic he would ask “you didn’t see me do that did you, because if I see you doing it you will be in trouble!”.

I found myself on one of several Monarch centre lathes imported from the USA during the last war. I think there were seven, one behind the other a decent working distance apart and another two along a wall side of the shop. The machines were, I think, fifteen feet between centres with a swing of eighteen inches. They were smart looking machines and relatively easy to operate and very versatile and I liked the fact that it was to be my machine. I was put on the lathe directly behind Dick Scholes where he could keep his eye on me and to answer the many questions, I initially asked. After a few months I became proficient in operating the machine and was moved further back in the row of Monarchs to a position between two star men. Harry Feathers and Teddy Higginson. These two men made during my time in that department so enjoyable and treated me in a grown up way but would occasionally pull my leg. I became a better turner because of them just watching and asking questions. While our machines were running we were able to talk with other lathe operators, about Rovers, King Georges Hall and radio etc. etc.

I was selected as the turner to make all the turned parts for the Rotocube Dry Powder Mixers all the drawings were contained in a large heavy duty folder. With separate sections for each size of mixer. A major part was creating a spherical shaped bearing unit this was quite a challenge to say the least.

Star men were people who were in the managements view a bit better at their jobs than others doing the same job. A star man earned two pounds per week more than a normal skilled man, quite a big difference in those days. It created some competition in the work place.

I was beginning to regret choosing to be an indentured apprentice and really enjoyed having my own machine and working on a wide range of very different products. I asked to see Mr Pheasy and found myself in his office again, feeling more of a man than the last time was there. He asked me to sit down and tell him why I wanted to be a craft apprentice from now on. I was studying for a National Certificate in engineering and I worried that by being a craft apprentice might hinder my eventual progress into the drawing office when the time came. He told me he had been monitoring my progress through the different departments and was impressed so far and, as far as he was concerned I was doing such a good job where I was and I could stay there until my twenty first birthday. When subject to good examination results I would become a trainee draughtsman. I was just over eighteen at that time and enjoying my life. I had met the girl of my dreams she was called Hilary Smith aged 17 who was then a draughtswoman at the General Post Office (now BT) I am still very happily married to her since 13th August 1960.

With my future virtually assured I returned to the Light Machine Shop for the rest of my apprenticeship. The days went by pleasurably, I had nice helpful colleagues plus several apprentice friends some older some younger we all hit it off. At break times the men would disperse to places where they could have a sit, smoke and a chat with their mates. We apprentices were no different but we tended to congregate behind one of the big milling machines. Various topics were discussed like Blackburn Rovers, Car racing, girls and last night’s radio programmes especially The Goon Show with Peter Sellars, Harry Seacome and the others, in what was a cult type of comedy show. If you got it, it was great, if you didn’t have a clue, you thought it was rubbish. As teenagers we got it and replayed it to ourselves and our mates miming all the crazy jokes and the voices of the participants on that show the previous night.

At weekends we (the lads) either played football or went down to Ewood Park. We all went dancing at King Georges Hall on Saturday nights with our outside work mates, which was where all the girls went too. The girls stood together on the left of the dance floor when facing the stage and the “famous” Jock Caton dance band. The boys on the right, both sets facing each other. The couples stood at the back of the room or sat up in the balcony. We on our side looked across at the girls seeking out the “special one” and they were looking over at us. It was customary for the man to go over and ask a girl to dance with him. Some girls danced together particularly when “Rock and Roll” became the norm. Despite there not being much money around we all managed to enjoy ourselves. Every Saturday we would dance with a girl we thought we really liked and would ask them if you could walk them home. They usually said yes but sometimes it was better to ask where they lived first!

My apprenticeship carried on with nothing of real note to tell, other than my skill on the lathe became proficient and I was able to operate the machine to full capacity and made few if any mistakes. I was just Alan Duffy “skilled Turner and Borer”. I was coming up to my twenty first birthday and still attending Blackburn College nights usually three a week. On the “grape vine” I heard there was a vacancy coming up in the drawing office. It was surely my turn I thought. To my shock the person given the job was another apprentice. He was not as skilled as I was, and no further ahead than me at College. I was mortified and asked for yet another meeting with Mr Pheasey which was granted quickly. As soon as I went into his office I saw that he was a little uncomfortable. He asked me to sit down and said he knew why I had asked for the interview. He apologised and said “Alan you have achieved everything I asked of you and yes you were the natural choice for the vacant position, but we are desperate for good turners like you, and the drawing office need extra help” I told him that I had achieved everything he expected of me and was very hurt at what had happened. I was being held back from the job I so wanted for being too good at the job I was doing. He said that he would ensure that my path to the drawing office would soon be opened and he would personally guarantee it.

It was back down to operating my lathe not knowing when my chance for promotion would come. After a few weeks it faded into the distance, then one morning right out of the blue Mr Pheasey walked into our shop (he was not that regular a visitor) Charlie flew out of his office virtually running over to the works manager and obviously thinking something must be badly wrong. There was not a man in the shop who could take their eyes off the two men, although everyone kept heads down doing what they were supposed to be doing. Mr Pheasey got into an animated conversation with Charlie who seemed to be standing his corner. It became apparent that I was the object of their conversation and started to feel embarrassed suddenly some agreement had been reached. Mr Pheasey looked me straight in the eye motioning me to join them. I switched off my machine, wiped my hands and falteringly stepped towards the two men waiting for me. I could feel the eyes of all my workmates upon me they must have been as confused as I was. When I stood in front of them Charlie said Mr Pheasey has something to tell you. Mr Pheasey put his hand in mine and said from tomorrow morning you will be working in the Planning Office. I blurted out that it was the drawing office I wanted. (The planning office is an “enemy” of shop floor workers like me working on piece work where times are set and to earn bonus you had to beat them. Lots of disputes crop up with the planners who don’t always see eye to eye with the work force.) Mr Pheasey looked me straight in the eye and told me,” I know this is not what you want, but the step up from the shop floor to the planning office is higher than the step up from planning office to the drawing office” Adding “you will never regret this” I stepped back and thanked him and said “I won’t let you down.” There was some jeering from my workmates when the bosses left but I think they were mostly happy for me.

Rotocube

PLANNING OFFICE

I started in the planning office at seven thirty the next morning and was introduced to my new colleagues including George Kemp who was to be my mentor. They were a nice but small group of people all much older than I was, but I soon settled in, there was good “banter” in the office but not of a kind that would be acceptable today. The boss of the department was a man called Jacob Etherington. He had his own office and I never really had contact with him.

After a few “okay” weeks in this office a rumour came out that Mr Pheasey was leaving the company after over thirty years. All the why? Questions, raged round the entire factory what would become of us? My question was “what would become of me now. Apparently trapped in an office I didn’t want to work in!” A few uncertain weeks passed by then it was his last week and he decided that he would come round the entire factory to see every single employee and say a last goodbye. It was a Friday afternoon. I hardly noticed him enter our office he just seemed to appear from nowhere. Suddenly he was at my side, hand outstretched he shook it firmly and said the words I wanted to hear. “Alan you have done what you said you would do, and I am doing what I promised you, report to Jim Garwood in the drawing office at nine on Monday morning. You are now a trainee draughtsman”

DRAWING OFFICE

So he did what he promised he would do if I kept to my side of the bargain. On the next Monday I entered the Drawing Office where Mr Jim Garwood was waiting. He said he was pleased to see me again after the years that had passed since my time as office boy. He took me round the office and introduced me to his staff it seemed a bit like old times, some familiar faces were still there. I specially remembered Doll Whittam the blind typist who when I was introduced said she remembered me as office boy. Mr Garwood told me to call him Jim and found a drawing board for me and there I was a full circle office boy to draughtsman. My parents had bought me some drawing implements to help my drawing. Jim gave me a little job to get me started and hey presto I had reached my first ambition.

The work in the general side of things where I worked was mainly estimating costs and checking outside engineering consultant’s drawings for errors and to prepare cost estimates for the machinery on the drawings FYT hoped to manufacture. Manufacturing steel rolling mills production lines and associated heavy precision equipment. A whole range of machinery for the chemical and steel industries were just the job for a company like FYT. The machines were run and tested before delivery in the massive machine shop. The Company had also contracts with the navy and had a separate department to handle this highly secret side of the business. They also produced some own designed products including hydraulic moulding presses and dry powder mixers which were designed in the Press Drawing Office a short distance away. Every time I visited the shop floor all of these types of equipment could be seen under construction it was an amazing place for a young aspiring engineer to learn his trade. As time wore on I became proficient at drawing and found out I had a brain that seemed to enjoy working out engineering problems. Thoughts of designing original machines from scratch became attractive but FYT was not the perfect place to do that.

At the time of my reaching twenty one the government had a conscription system where young men aged eighteen and over were required to serve in HM forces for a period of two years. For those who were studying for higher engineering qualifications like myself we could ask for a deferment which allowed a man to keep working instead of serving. You could ask to be deferred twice then you had to join up. I was at this stage and having passed my army medical and intelligence tests I was told that I was due to be called up in a matter of days. On my way into work one morning at this time I was greeted by Jim Garwood who ushered me into his office all very mysterious. He asked me to sit down and said “you are due for call up anytime now” I nodded and then he asked “do you really want to serve in the army” what sort of question was that? “Absolutely not” I said. “I can get you another two years deferment if you sign this paper” he flourished a document in my face I took hold of it asking “where do I sign?” In a matter of moments the deed was done. I had signed up to becoming civilian, seconded to HM Admiralty for a period of two years. I would work on those projects carrying the security level of “secret” which FYT were working on at that time. I was immediately that day! Transferred into the Admiralty Office in a corner of the general office. I worked there with a colleague Raymond Cragg for the rest of my time with the Company until conscription was ended. Then because I was getting married and needed more money than FYT would pay. With no regrets I left to join another big company in Blackburn called Mullards who were part of the Dutch giant Phillips. It was there I was to be given full opportunity to fulfil my desire to design special purpose machinery and realised that this was my future ambition.

Foster Yates and Thom Sales Exibition

MY LATER CAREER

I had a very successful engineering career achieving C. Eng. M. I. Mech. E in June 1968 studying at Blackburn Technical College. My attendance at college was done mostly at nights after work. Three sometimes four nights a week 7 till 9.30 and I attended for a period of twelve years.

My career after FYT was Mullards Ltd. Electronic vales machine design, Crompton and Knowles Ltd Nelson, Packaging Machine Design and Manufacture, British Aircraft Corporation, Warton Senior works engineer, British Oxygen Company Rotherham Production engineer, Netlon Ltd. Blackburn Head of R&D, Pioneer Oil Seals and Moulding Ltd. Chief Engineer, W Houghton Ltd Clitheroe, General Manager.

After working for others I decided with the aid of a government grant to launch my own Engineering Company called Alan Duffy Engineering Ltd.in 1983. We manufactured and designed state of the art slitting and rewinding machines for the Converting Industry and exported worldwide we were hugely successful and attracted the attention of a major American Group and sold them the company in 1987. Several years later after the Americans decided to move the Company to the USA making the all the staff in Blackburn redundant. I decided to start another engineering company we called Delta Converting Equipment Ltd. Because of a host of business issues we were not as successful as before and with great reluctance made the decision to put the company into administration and retired in 2022.

back to top

Published December 2023