Bits Of Old Darwen

The Town In Other Days

From the Blackburn

Weekly Telegraph January 17th 1914

There was a Time when cherry trees yielded crops of fruit on

the north-east side of Bowling Green Mill—by some claimed to be the first

power-loom mill in Darwen—and when the gardens now a part of Low Hill, between

the mill and Bury Fold Lane, were all green fields. These times are yet fresh,

though so far distant, in the memories of the few real old Darweners who

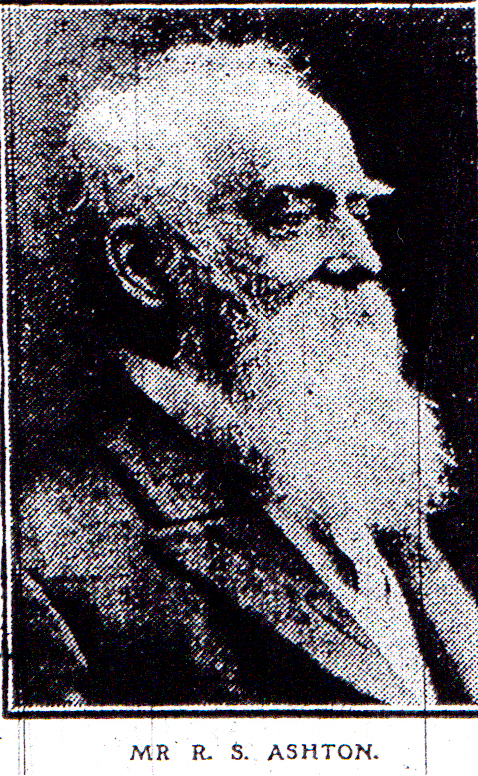

survive. Amongst those who never forget the Darwen that was is Mr. Ralph

Shorrock Ashton, whose review, going back to the days of his youth—he is now

83—is crowded with happy recollections of Darwen and its people. Mr Ashton now

lives in London, he has been away for many years.

Woodlands, where William Huntington lived later on, and now the residence of

Mr. George Yates was built by Mr. Ashton’s father, who came to Darwen in the

[eighteen] thirties, and so did Mr. Eccles Shorrock. Mr. Ashton’s father

married for his second wife a Miss Shorrock of Prince’s. Ralph Shorrock Ashton

laboured for a high standard of life and was connected with the establishment

of the old Mechanic’s Institute, to which so many now prominent Daren men admit

they owe the foundation of their careers. And he served his district for a term

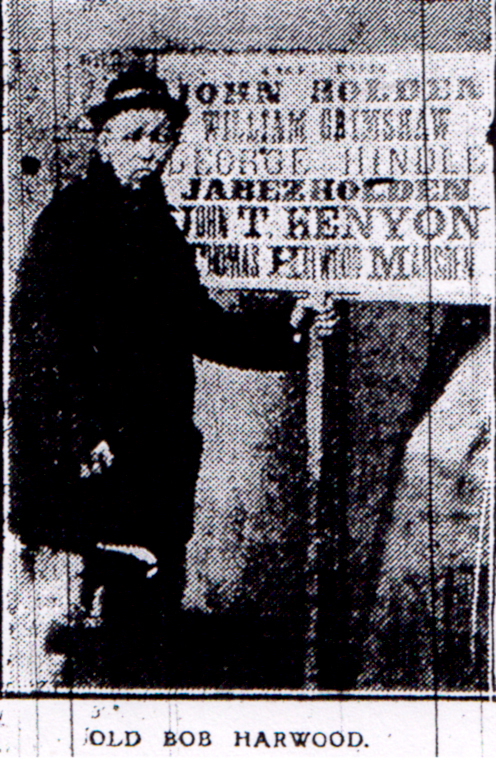

as chairman of the old Local Board. The picture I am able to publish of old Bob

Harwood carrying an electioneering board is an interesting reminder of the

fights there were for seats upon the Board. Connections of Mr. Ashton’s

stepmother’s family were influential at the beginning of the dead (sic)

century, when Darwen was no more than a wayside hamlet, separated from outside

districts by the difficulties of traveling. They saw it awaken to its

possibilities, and in no small degree assisted to develop its energies in many

directions. Calico printing and bleaching had been introduced as profitable

industries four and forty years before the days of Mr Ralph Shorrock Ashton’s

boyhood began. Old James Greenway had added them to the industries of

coal-getting and hand-loom weaving. Mr Ashton was born early enough to see

power-loom weaving in its infancy at Darwen, though he was not living at its

birth. Four years before he saw the light of revolutionary power-looms set up

at Bowling Green Mill, popularly known as “Top Factory,” had been smashed by

indignant hand-loom weavers, who feared that the innovation meant starvation

for themselves, and they also similarly treated the loom of Mr. James Grime. In

the evening of Mr. Ashton’s long and eventful life many incidents and stories

of the Darwen of by-gone days recur to him, and some of these I have been

fortunate enough to obtain from him, and am permitted to include in this series

of articles.

Darwen is not the Darwen it was when Mr. Ashton was a boy. Gone are the

well-grown trees from the Anchor to Dove Cottage, and houses and other

buildings now stand where they were rooted. The approach to Bowling green Mill

from Sandhills had trees on either side of the road, but these have

disappeared. The workers at the mill who lived in Bury Fold came by a footpath

turning out of the lane at a spot close to Low Hill, and through the fields.

The Holmes, Stoney Flatts and the land northward of Darwen Mills were not built

upon, and neither was the Lea. Nicholas Holden’s farm near Woodside Mill was in

the country. Shorey Bank was a country residence and its gardens full of fruit

trees. Behind were grazing fields, sloping down on which flocks grazed,

encircled by a rivulet which came down from Marsh House. The fields stretched

away to Sudell Road and Trinity Church.

Darwen is not the Darwen it was when Mr. Ashton was a boy. Gone are the

well-grown trees from the Anchor to Dove Cottage, and houses and other

buildings now stand where they were rooted. The approach to Bowling green Mill

from Sandhills had trees on either side of the road, but these have

disappeared. The workers at the mill who lived in Bury Fold came by a footpath

turning out of the lane at a spot close to Low Hill, and through the fields.

The Holmes, Stoney Flatts and the land northward of Darwen Mills were not built

upon, and neither was the Lea. Nicholas Holden’s farm near Woodside Mill was in

the country. Shorey Bank was a country residence and its gardens full of fruit

trees. Behind were grazing fields, sloping down on which flocks grazed,

encircled by a rivulet which came down from Marsh House. The fields stretched

away to Sudell Road and Trinity Church.

“Hand-loom weaving was common in my early days.” Mr Aston says. “The farmers on

the hillsides added little to their incomes by weaving in sheds adjoining their

houses. And the occupation was not confined to farmers. As a boy I was much

interested in the scenes at Prince’s in the days of old Mr. Shorrock, who gave

out yarn, cops and warps to the weavers around to be woven into cloth, which he

afterwards sent to Manchester for sale. It was at Prince’s that the father of

the late Christopher Shorrock was born.

“Social conditions have greatly changed since the [eighteen] thirties. An

average workman who earned 12s a week considered himself well off; masons got

from 3s to 3s 6d a day, labourers 2s and quarrymen 2s to 2s 6d, colliers 12s to

15s a week. Hours in the factory were long, from 3.30 in the morning to 7.30 at

night, and on Saturdays till 4 in the afternoon. During the winter months

colliers never saw the light of day except on Sunday. Food was dear, foreign

corn was then kept out to help the landlords, and the principal food was

oatmeal porridge and buttermilk. Coal was cheap. Good housefire coal could be

brought at 7s 6d a ton and steam at 5s a ton.

“Mrs Shaw—a worthy old lady—lived at the Bowling Green Inn. Soldiers were

quartered upon her during the plug-drawing riots of [18]26 and some of them

went away without paying though she said they `reckoned fair.‘

“I remember with interest the paper-works at Darwen Mills established and

worked by Messrs. Hilton, and supplied with coal from the Dogshaw mines at the

top of Darwen Moors. The coal was brought down by a railway running under

Bolton Road up past Radfield, and onto the moor. The trams consisted of eight

waggons. Four laden with coal drew up the four empty ones. There is a matter of

interest connected with the mines. Those called the 20-inch mines were mostly

worked in Darwen, Entwistle and Hoddlesdon.

“My early recollections carry me back to an old pit behind Darwen Mills, long

since unused as having been worked out. The 20-inch mine supplied good coal, as

did the many other mines spread about the valley. The pit behind the mill was

about 80 to 100yards deep, I think, but below that mine lies a rich mine about

70 yards lower. This was called the yard mine, but it was not considered

profitable to sink down so low owing to the water, which would have to be

pumped up at great expense. At Dogshaw on the Moor, 1,400ft. high, I think,

which was worked by the railway I have mentioned, there were two mines—the 20in

mine and the yard mines—almost on the same level. How came they then in

contrast with the mines 70 to 80 yards below Darwen Mills? The explanation is

that there is what in geology is known as a fault running along the road

leading from Bolton to Darwen, and this marked a great volcanic upheaval in

past days. The mines were thrown up on high, and not only so, but they must

have had special upheaval to have been thrown up almost to the same level as

the 20in mine. The coal from the yard mine was splendid. How glad the people of

Darwen would be if now they could enjoy the same supply of coal as that which

prevailed even during the [18]50’s, when it was laid down at the people’s doors

at 7s 6d per ton, and steam coal obtained at 5s a ton.

“At the beginning of the 19th century Darwen was traversed by two

high roads from north to south. The best of these followed the ridge of the

hill on the east side from Eccleshill and over Blacksnape, and was part of the

ancient road from Blackburn to Bury and Manchester. The other, a packhorse

road, narrow, crooked, circuitous, and ill kept was from Chapels down from

robin Bank, across the River Darwen by the ford where Union Street Bridge is

now. When in flood the river was impassable, and had power and depth sufficient

to carry down a horse and rider, as in the case of Mrs. Bowden in 1804. The

track continued passing behind Smalley’s Hotel, now Gregg’s Hotel, down the

Green up Bridge street, where there was a second ford of the river up Redearth

Road, on to Sough, twisting back again by Watery Lane and the present site of

Culvert School, and south-wards over the fields to Cadshaw Bridge and Bolton.

It was the main road between Blackburn and Bolton, and there were frequent

trains of packhorses bringing commodities and supplies.

“Squire Greenway was the only man who could live on his means without the

necessity of trade or profession. Two others might lay claim to honour. These

were old Lawrence Burry, Of Kebb’s and another well-known Character of the days

of my boyhood whose chief employment was to take their children’s meals to the

mills, stand at the corner and pick up gossip. The father of squire Greenway

was a shrewd man, and made his money as a calico printer at Dob Meadows. In

those days pieces that were bleached and printed would be put out in the fields

on rails to get the chemical effect of the air or to dry. Thefts were committed

in the night, and the watchman was given a gun and set to keep sharp outlook.

One Morning he met Mr. Greenway with a long face and said `Heigh Mester

Greenway, they’n been and ta’en my blunderbuss.` the man was promptly

dismissed. Mr Greenway was always dressed plainly, and one day coming to his

counting house he was accosted by a traveller who did not known him, and asked

him to hold his horse. He did so, and the traveller went inside to transact

business. On returning he gave Mr. Greenway half a crow. The old gentleman went

inside and asked who the traveller was? On being told he said, `Give him no

more orders. If he can afford to give me half a crown for holding his horse a

quarter of an hour or so, depend upon it he is getting to much out of me in

extra charges.

“Squire Greenway was the only man who could live on his means without the

necessity of trade or profession. Two others might lay claim to honour. These

were old Lawrence Burry, Of Kebb’s and another well-known Character of the days

of my boyhood whose chief employment was to take their children’s meals to the

mills, stand at the corner and pick up gossip. The father of squire Greenway

was a shrewd man, and made his money as a calico printer at Dob Meadows. In

those days pieces that were bleached and printed would be put out in the fields

on rails to get the chemical effect of the air or to dry. Thefts were committed

in the night, and the watchman was given a gun and set to keep sharp outlook.

One Morning he met Mr. Greenway with a long face and said `Heigh Mester

Greenway, they’n been and ta’en my blunderbuss.` the man was promptly

dismissed. Mr Greenway was always dressed plainly, and one day coming to his

counting house he was accosted by a traveller who did not known him, and asked

him to hold his horse. He did so, and the traveller went inside to transact

business. On returning he gave Mr. Greenway half a crow. The old gentleman went

inside and asked who the traveller was? On being told he said, `Give him no

more orders. If he can afford to give me half a crown for holding his horse a

quarter of an hour or so, depend upon it he is getting to much out of me in

extra charges.

“Mr Hoghton Ainsworth, who ran the loom-shed called Springfield Mill in Bolton

Road, was a stern old Puritan, and claimed to be something of a theologian. His

dress was a black tail-coat, such as gentlemen use nowadays for evening dress.

And he wore white stockings and low shoes. Mr. Eccles Shorrock senior, was the

first to adopt morning dress. A young swell at Blackpool would were white

trousers, white stockings, and brilliant patent leather pumps. His shirt front

would be elaborately got up with frills that had been put through a goffering

machine. And his hat would be a fine beaver.

“My first school was a mixed school for boys and girls kept by an old lady of

the name of Mrs. Entwistle. She lived first in a house just opposite Ebenezer

Capel, and next in Union Street when New Mill was being built. I can remember

the fireproof arches over the boilers falling in and killing a poor man whom we

saw carried out on a stretcher.

One of my school-fellows was Miss Pickup, a daughter of William Pickup, of

Marsh House. She was somewhat older than I, and very kind in helping me to do

my multiplication tables. My next school was that of Mrs Ianson and her

daughter, who kept a school in a house at the corner of Bentley’s woodyard,

which was then opposite the present Co-operative Stores. The woodyard was the

playground of the school-children. The Openshaw’ and the Cunliffes were also at

the school.

“Mrs Ianson was postmistress, and I have seen her and her daughter examining

the letters very carefully, taking them up and holding them to the light. This

was done not because she was prying into people’s secrets, but because those

were the days of dear postage, and it was her duty to examine letters and see

if they had any enclosures. If any were found the postage charge was doubled.

Letters were charged for according to the distance carried. The charge for 300

miles for a single sheet was one shilling. Double sheets were treated as two

letters. It was owing to the double charge that the postmistress examined the

letters.

“It is a matter of interest to know that in 1831 a meeting was held at Darwen

in support of the great Reform Bill. The speakers were Mr. Harry Hilton, the

Rev. S.A. Nicholas (of Lower Chapel) Mr. Eccles Shorrock, the Rev. L.A. Hague

(of the old Ebenezer Chapel) and Mr. William Hutchingson. Mr. Richard Hilton’s

father, I think, of Mr. Henry and Mr. Edward Hilton, was in the chair. Mr.

Henry and Mr. Edward worked the paper mill in my young days. In 1832 Darwen,

then a small place, paid more duties to Government than its larger neighbour Blackburn.

This was owing to the heavy duty on paper which was levied at the paper works

before the paper was allowed to be taken away.

“The Rev. S.T. Porter of the old Ebenezer Chapel and of Belgrave Independent

Meeting House was the mainspring of the establishment of the mechanics

Institution in 1839, and I can see him now in a long dressing gown in a room

devoted to the infant institution.

“Every woman had a chance of getting married if she wanted to in the [18]30’s,

for the census showed that there were 3,421 males and 3,551 females in the town

, and 1,202 families living in 1,252 houses. There were few `quality` folk, and

only 28 female servants.

“In Sough Village old James Pickup and William Shorrock lived, and they were

two careful bodies. `does ta’ know ‘at when tha’rt spending a ha’penny tha’rt

spending both capital and interest,` old James would say. Money was valued

because it was hard earned. A man once remarked, `What’s the use of working and

saving? Thoase ‘at come after will spend it.` `Aye Aye,` replied the one to

whom he spoke `an if they hev as much pleasure I’ th’ spending as I’ve hed I’

th’ saving of it they’re welcome.

“Funerals were made a lot of when I was a lad. At Bowling Green Mill there was

a joiner who was better of than many others and wore good broadcloth. He was

often asking off to go to funerals, and it was thought the reason was because

he was so well dressed and looked so respectable. He was regularly placed on

the front seat of the mourning coach.

“Bowling Green Mill taught Darwen how to spin, and gave work out to many of the

great-grandfathers and great-grandmothers of the present generation. When it

could not spin it made room for Robert Nightingale’s old curiosity shop of

domestic and literary stores. And old Robert has passed away, and his shop is

closed.”

The contemporaries of

Mr. Ashton were Mr. Greenway, uncle of the late Rev. Charles Greenway and known

as Squire Greenway and had considerable property, The Potters, the Hiltons, who

have a vault at Lower Darwen, The Brandwoods, who were colliery proprietors,

the Wardleys, the Walshes, Seth Harwood, the overseer, and the pickups amongst

others.

Mr Ashton recalls a good story of old Lower Chapel. He says that;

“the children upstairs were under the care of a teacher who would make a ball

of his pocket handkerchief and throw it at a boy or girl who was talkative or

restless< The late Alderman Christopher Shorrock was a boy who was sent by

his father to a special service at the chapel, and his father gave him the

money for the special collection. Chris sat in a great square pew one Sunday,

and when the collection time came he could not find the money. Every pocket was

searched. Marbles, nails, a penknife, and other things were turned out, but the

money could not be found. Nearer and nearer came the collection-box, and at

length it reached young Chris, whose face was by this time scarlet. The

collector was not to be done. `What hesta done wi’ t’ money?` He asked, `for I

know thy feyther wodn’t send tha beawt.` He put down his box in the pew, got

old of little Chris and turned his pockets out one by one until the money was

found.

“Another story of Lower Chapel is that in the days of the candle the

chapel-keeper would go round snuffing them with his fingers. Snuffers were at

length introduced, but he did not take kindly to the new-fangled things and

would go round with the snuffers in his left hand. The candel he would snuff

with the fingers of his right hand, and the burnt wick he would deposit in the

box of the snuffer.

“Darwen had no lawyers in the old days and we had to go to Blackburn for our

law. All the letters were brought by a postman on foot from Blackburn to

Darwen. It was not an uncommon thing for Mr Eccles Shorrock to send someone,

some times my brother, on horseback to meet old William, and old Waterloo

veteran, and get the Darwen post-bag from him.

“The progenitors of Pole Lane Chapel and Ebenezer were mostly farmers and

weavers, Nathaniel Hunt, the father of Jeremy, promised £50 to the building

fund of Pole Lane. Jeremy, in after days was an enthusiast, and after walking

all the way from Pickup Bank to the service at Ebenezer, would go without his

Sunday’s dinner in order to give the money to the chapel debt. Another, a young

woman, went without her summer gloves, and gave the money at the Sunday School

collections. I remember the service; the men in their drab coats, and the women

in their big bonnets, with shawls flowing over their simple dresses of brown,

blue or red merinos, and nearly all carrying an old-fashioned posy. Ebenezer

had a grand base fiddle, which as a child I regarded with awe; William Becket

played the fiddle and Jeremy Hunt led the singing.

back to top