In 1581 the Talbots sold their Rishton estate to Thomas Walmesley and he proposed to use the whole of the chapel as a family mausoleum.

Sir Thomas Walmesley owned Dunkenhalgh and Hacking Hall estates. He rebuilt both Hacking Hall & Dunkenhalgh Hall.

Hacking Hall

Dunkenhalgh Hall

Sir Thomas Walmesley died 1612 and is buried in the de Rishton chapel.

The tomb was the exact counterpart of the one we see below, which is the tomb of the Anne Duchess of Somerset and is in Westminster Abbey.

Sir Thomas Walmesley is here entombed who was a judge of common-pleas in the 31 years of Queen Elizabeth and continued a judge of that bench25 years above. During which time he went to all the circuits of England except that of Norfolke and Suffolke.

He died the 26th day of November 1612 having lived 75 years

compleat under five severall Princes.King Henry the 8th,King Edward the 6th,Queen Mary,

Queen Elizabeth, and our sovereign King James.

He left behind him ( who are yet living ) Anne his Lady and sole wife and also one only Son Thomas Walmesley sole heyre to them both.

Whom in his life time he saw twice married. First Eleanor sister to Henry Lord Danvers and daughter to Sir John Danvers by Elizabeth his wife and comeyres of the Lord Latimer.

And secondly to Mary sister of Sir Richard Hoghton Baronett:

By both whom he saw issue. By his first wife one Son and two Daughters.

Thomas, Elizabeth, & Anne. By second one a son Charles.

The tomb of Judge Thomas Walmesley was smashed to bits by some of Cromwell's men during the Civil War.The market cross was also damaged at the same time.

On the East wall of the South transept of the Cathedral you will find this coat of Arms.

This piece came from the smashed tomb of Judge Walmesley.

Outside the Cathedral you will see the tomb of the Petre family.This tomb is on the site of the Judge Walmesley vault, as Petre married into the Walmesley family and the Petres became Lords of the Manor of Rishton. The Petre tomb also marks where the de Rishton chapel was in the old Parish Church.

The Petre Tomb

Coat of Arms on the Petre Tomb

On the north side of St, Mary’s Parish Church was another chapel.This was the Osbaldestons' mortuary chapel.Against the wall in this chapel were two brasses:

One with the bald head of an old man with a grey beard, his body armed.

Inscribed:- Here lyeth the body of Sir Edward Osbaldeston a charitable, courteous, and valiant Knight, qui obiit A.D.1636 aet 63.

The epitaph is concise, but contains a character replete with all the requistes of chivalry in its period of utmost purity.

The other brass is in memory of another Osbaldeston (Edward son of Alexander),which acquaints us with nothing further than that he died in 1689, aged 38.

There were also two more Coats of Arms hanging in the de Rishton chapel.

When St. Mary’s church was demolished these coats of arms which are on canvas one were to be found in the choir vestry of the Cathedral. The second one on canvas was said to be fixed to the wall of the staircase. Number 2 on the drawing below is of the Coat of Arms that was in the choir vestry, and shows the Petre Crest.

The other coat of arms on canvas is of the Walmesley crest impaled with the arms of Lord Stourton.

On this picture you can see the south side of the church and the south

De Rishton chapel can be seen at the back corner of the church

The Torbocs did not give up their claim to Turton until 1500 and, of course, during this time the Orrells of Turton laid claim to the Torboc estates at Tarbuck. But the Torbocs were not the only critics that the Orrells had to face. When Henry VIII attacked the Roman Catholic Church and confiscated the wealth of the monasteries, the Orrells of Turton chose to remain Catholic. John, the head of the family at the time, was the grandson of the original William and Elizabeth's grandson.

The scene of life at the Tower in John Orrell's time was not one of great luxury. He owned horses, cattle and sheep. Sheep-breeding was a traditional source of income in Lancashire. There were stores of wool and flax at the Tower and, on a more peaceful note, the family were able to relax to the music of a virginal.

But John was not a quiet man. Instead of hiding from the new religious order, he demanded recognition that several items in the local chapel, including a bell and a chalice, were his heirlooms. This was the chapel, on the site of Chapeltown Church, that was to change the village of Turton's name to Chapeltown.

And John found himself at odds with his neighbours again but not about religion. According to court records of 1560, he, ". . . of his great might and power, with force of arms, entered upon Turton Moor and enclosed certain parcels of ground, to the utter disinheritance of Christopher Horrocks." This was provocation! Christopher Horrocks retaliated. He, ". . . and about twenty others, armed with long pikes, staves, bows, arrows, swords, spades and short daggers, did assemble at the enclosure and did cast down and destroy the same."

The enclosure movement, which was to change the face of the eighteenth century English countryside, had in Elizabethan Turton already begun.

Change

At some time during the sixteenth century the timbered south-wing and hallway were added to the Tower. This work may have been carried out while John Orrell was Lord of the Manor. It was certainly continued after he had been laid to rest in Bolton Parish Church. The man responsible then was John's son and successor, William.

About 1596 the stone tower itself was altered. Its height was increased by a third. This was not to add an extra storey to the building but to raise the height of the floors that were already there. The difference in the stonework can be seen from outside, and on the top floor you can see traces of earlier windows on a level with your feet.

The only signs of the mediaeval interior to survive are parts of a stone spiral staircase and a garde-robe or toilet.

In two ways William succeeded in putting Turton on the map. The first of these he could perhaps have wished to do without. In 1590 a chart of Lancashire was prepared for Queen Elizabeth's adviser, Lord Burghley, marking the homes of prominent Roman Catholics. On this map, not far from a stream called "Turton Water", stands a building with the words, "Orel de Turton".

The Tower's second geographical reference was made a few years later when Turton was visited by the chronicler William Camden. This inveterate traveller had set out from Bury, in the hope of discovering the site of the Roman settlement of Coccium. Instead he found himself "among precipices and wastes" at Turton Chapel and at Turton Tower, "the residence of the illustrious family of Orell".

Sad to say, the Orrells had only a few years left at the Tower. William, in making his improvements, had overspent. Possibly also John, his son and heir, was weak with money. The truth is that the year after the death of this second John, his younger brother was obliged to sell the estate.

Turton's Lords of the Manor, in the reign of King John, were the Torbocs. Far from being a local family, they came, as their name suggests, from Tarbuck, on Merseyside. For their position at Turton they paid feudal dues to their overlords, the barons of Manchester.

Then, about 1420, John de Torboc died. Since his son died soon after him, his lands were divided between his daughter, Elizabeth, and her Torboc cousins. While the cousins were given Tarbuck, the manor of Turton was inherited by Elizabeth.

It was about this time that Turton Tower was built. Made of stone and rectangular in shape, the building belongs to the group known as pele-towers. These had been popular in northern England and Scotland since the days of Robert the Bruce, a hundred years earlier. It may have been built to suit the wishes of Elizabeth's guardian, Sir John Stanley, or perhaps his relations, the Orrell family of Wigan.

Elizabeth was destined to be married into that household. She was married to William Orrell of Wigan. Although Elizabeth's Torboc cousins were to continue to lay legal claim to Turton, the Orrell family moved in and settled to become the earliest recorded residents of Turton Tower.

The name of the last Orrell to own Turton Tower was the same as the first there, William. At first William set out to seek a loan of £1,000 from the Manchester banker and textile merchant, Humphrey Chetham. Not many months later, in 1628, Chetham paid him £4,000 for the Tower, the estate, the Lordship of the Manor and all the rights associated with it.

Humphrey Chetham was a wealthy man. He had already acquired a manor house at Clayton Hall on the other side of Manchester and he kept this as his first home.

So when a King's Messenger arrived at the Tower one summer's day, three years later, the owner was nowhere to be found. Thismessage was left for him,

"Mr. Humphrey Chetham of Turton,

You are by virtue of a Warrant directed to me from the Lords of the Most Honourable Privy Council being Commissioners appointed by His Majesty's Commands with those not appearing at His Majesty's Crownonacon to take upon them the Order of Knighthood. You are therefore to appear before their Lordships at Whitehall on the XXth day of October next: whereof you are not to fayle as you will answere the contrary at your perill.

Dated at yor howse this 30th day of August, 1631.

Your loving friend to Comand

Franncis Taylor

One of the Messengers of His majesty's Chamber".

In the reign of King Charles I the offer of a knighthood was less an honour than an imposition for which one had to pay. Like many other men, Humphrey Chetham chose to reject the knighthood and be fined. Four years later he could not refuse the duty of serving for a year as High Sheriff of Lancashire. The usual burden of this office was to have to pay for the board and lodging of the Justices attending the Assizes at Lancaster.

Humphrey asked George, his nephew in London, to send him all he needed that was not available in Manchester, and he sent his steward, James Walmsley of Turton, to negotiate the best terms he could with the Keeper of Lancaster Castle.

As Sheriff, Humphrey suffered a more onerous year than most in being responsible for collecting King Charles's "Ship money" from the county. This was another attempt by the King to raise funds independently of Parliament.

It is not surprising that, when the Civil War broke out in 1642, Humphrey Chetham was found on the side of the Roundheads. As one of Manchester's leading financiers, he was appointed treasurer for the cause in Lancashire. As Lord of the Manor he raised and equipped Turton's soldiers and the Tower was used for quartering Roundhead troops. In 1645 he recorded, "In free quarters at Turton to maiors and captaines by 2 or 3 at a time for divers times and to Troups sometymes 12 sometymes 16, sometymes 20, sometymes more. And likewise in foot sometymes 60 or 70 a night and daily relieveinge of horse and foote especiallie at that tyme when Preston was regained from us to the enemy, at wch tyme for divers weeks my servants were forced to brew and bake almost everie daie for the reliefe of the afforesaid Souldiers that came to my howse of wch it is impossible for me to give a p'fect accompt."

Humphrey took an interest in Turton. In the Civil War correspondence was often addressed to "Humphrey Chetham of Turton" or "Humphrey Chetham att Turton". When he died in 1653 he left funds for the education of children in Turton and a library, which still survives, in the Parish Church.

But whereas Humphrey tended to use Clayton Hall in Droylsden as his home, he left Turton Tower for the use, in 1648, of his nephew, George.

If Humphrey Chetham had been a rich man, then so was his nephew, George. And this was not a young man. When he inherited Turton Tower on his uncle's death, George was already about sixty years old.

In his younger days George had been a merchant in Italy, and then he set himself up in the City of London. His position became so well established there that in 1656 he served as an Alderman and as Sheriff of the City. He later served as Sheriff of Lancashire.

While George Chetham was Lord of the Manor, Turton Tower received probably the most lavish furnishing it had ever had. There were four-poster beds and feather and down mattresses for the family; and, for the servants, trestle-beds and straw. The dining room had green cushions and a green carpet; there were green curtains and a green bedspread for the wife's bedroom. The estate had a couple of hundred sheep and a couple of dozen cows and oxen. In the cheesechamber were a score of cheeses. With gold buttons for his clothes, £150 worth of silver plate and £1,300 worth of cash in the Tower, there can have been little that George Chetham lacked.

Yet he was not always a happy man. In February, 1659, his son, Humphrey, passed away at the Tower. He was only twenty-three but he must have known he was going to die. George's son-in-law who was, at one time, the minister of Chapeltown, tells us,"He had his coffin by him, and oh, how pleasantly would he discourse of death, and of his bed in his study (there his coffin stood)."

As George walked on Dove Hill, where the Summer-House stands, he was told to think of his son "walking with Christ in white". He spent £ 170 on the funeral. Five years later George also was dead.

George was succeeded by his son and his grandsons. In 1748, when the second grandson died, the inheritance passed to another grandson, his cousin, Edward. But Edward was the last of the Chethams. He left no children and his sisters had interests elsewhere. So, in the 1770's, we find the Tower being leased to tenant farmers.

George's descendants were still the Lords and Ladies of the Manor. The local magistrates' court was conducted in their name. In the ballad of the riotous Turton Fair, published in 1789, we hear an appeal to the Lady of the Manor to intervene there. The Lady referred to was Edward's niece, Mrs. Mordecai Greene, "Because she's solely vested with a pow'r That will avail in this distressing hour."

Her son, James, M.P. for Arundel, sent silver goblets to be given as prizes at the Turton Agricultural Show.

But John Healey, Samuel Hall and William Horrocks, used the Tower as tenant farmers. Pig-sties and a new coach-house were built for them. Meat and ale were given to the carters who brought the materials to build them.

With each generation the family's bonds with Turton Tower grew weaker. Then in 1833 several prominent citizens of Turton sent a letter to James Greene's son-in-law. Out of deference to Humphrey Chetham, the man whose charities had aided their education, they wanted to erect a monument to him on Chetham's Close hill-top. They were disappointed with the reply to their letter. They had at least expected a contribution to the funds. But the man they had written to was an ironmaster near Swansea. He had other interests to concern him than the moors of Lancashire.

Two years later he and his wife sold Turton Tower and 365 acres to James Kay.

James Kay was a local man who had made good through harnessing steam power to the spinning of flax. It is said that since his youth he had cherished an ambition to be the Lord of the Manor of Turton and to live in Turton Tower. Now he had become a manufacturer, with spinning mills in Manchester and Preston and with money in his pocket, he was determined to restore the Tower to its former glory.

A new stone frontage was given to the cottage wing of the Tower. Beside the main porch the gable enclosing the staircase was widened considerably, and new rooms, the Ashworth and the Bradshaw Rooms were added.

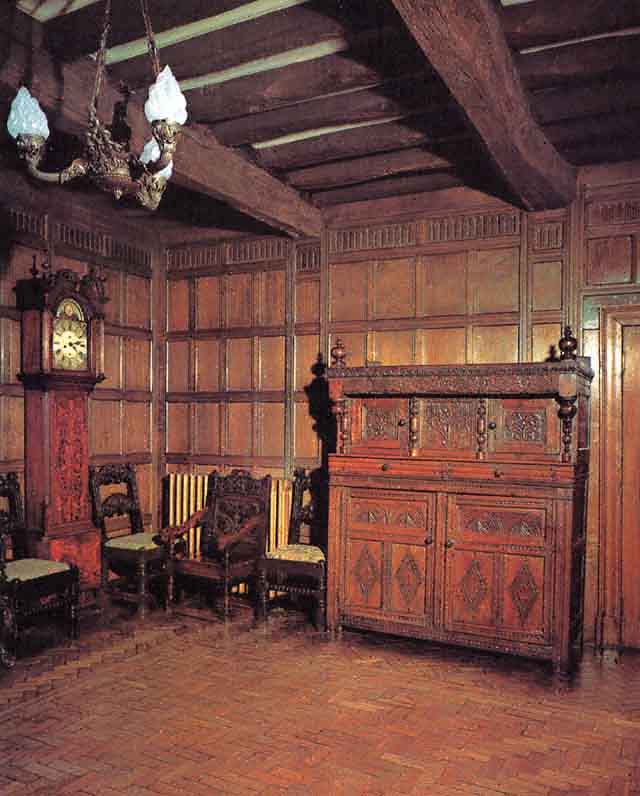

With Middleton Hall in Manchester being demolished, some of its panelling was brought to furnish the walls of the Dining Room. Panes of Swiss stained glass were set into the upper part of the Dining Room windows. And in the Drawing Room the fine Elizabethan ceiling was restored. When the railway line between Bolton and Blackburn was cut at the back of the coach-house between 1845 and 1848, two bridges were built across it, with turrets and castellated walls to be in keeping with the Tower.

When James's grandson, another James, inherited the estate he adopted the way of life of a country squire.

The Kays used to play tennis, billiards, the piano: and the local hunt used to meet at the Tower. In the building itself the servants were housed in the east-wing, while the family occupied the original Tower.

Several items from their time can still be seen. A German chandelier of the early nineteenth century, made out of antlers; a German seventeenth century wood-carving depicting the Last Supper; and a hugh four-poster bed which stands in the Tapestry Room. Sleeping there, one night, in the later years of the century, was the head-nurse, a lady who had been engaged by the first James Kay at Cheltenham. That night the great bed shook and the people of the Tower feared the ghosts of the Tower were walking, until the following morning a neighbour calling asked if they had felt the earthquake.

In 1890 the Tower and its contents were sold again.