Blackburn Wakes Weeks

Blackburn was unusual in that a traditional wake had not survived into the 19th century - instead an annual Easter Fair became the town's main holiday event. Traditionally, Blackburn's Easter Fair was held on the large tract of open ground known as Blakeley (or Blakey) Moor . In the 1830s, it was still a largely agricultural event, as noted by the Blackburn Alfred of April 10th 1833:

'Our fair commenced on Monday last, and owing to the fineness of this day, the attendance was great. An unusual quantity of cattle was shown but there was a wretched display of horses etc. The shows are in abundance and the country people, dressed in their holiday attire, crowd en masse to witness the mountebank tricks of the strollers. They will reap a good harvest we imagine, if the spirit do not relax.'

By Nick Harling

Robert Poole, author of 'Lancashire Wakes Weeks' notes that many of the traditional wakes customs died out during the industrial revolution. The rural sports of bull-baiting and cock-fighting were banned during the 19th century, and bare-knuckle fighting eventually waned in popularity. Wakes fairs were gradually transformed from bloody spectacles into more genteel affairs. Picnicking was encouraged and 'entertainments' in the form of fairground rides, circuses and stalls replaced contests of strength.

However, the biggest change in wakes tradition came about with improved transportation, in particular the advent of the 'railway excursion'. This had the effect of removing the focus of the wakes celebration away from individual towns towards rapidly growing holiday resorts such as Blackpool. Lancashire's railway system, which developed primarily to serve the needs of the county's thriving industries, had the added advantage of opening up hitherto inaccessible areas of country and seaside to day trippers.

Railway companies were quick to respond with organised excursions, aimed directly at workers celebrating their wakes holiday. The fact that most town's wakes weeks did not correspond with each other simply encouraged the railway companies to lay on more trips.

By Nick Harling

During Lancashire's industrial era, the most widely anticipated time of the year was the annual summer holiday, generally known as the Wakes Week. The origin of the wakes are to a certain extent still shrouded in mystery, although it seems likely that they were originally intended to commemorate the anniversary of a church or chapel being founded in the local area. However, by the 19th century, the wakes had few religious connotations, although 'rush-bearing' processions to the local church continued in some parishes for many decades.

The Lancashire wakes are best seen as a tradition which became an institution. Each town in the cotton belt had celebrated the wakes in one form or another for centuries before the industrial revolution. Once their lives were regimented by the mill clock, most factory workers felt even more strongly that this traditional 'time-off' should be preserved and formalised.

Each town had its own insular tradition, which eventually developed into a 'week off work' - consequently, local towns took their weeks at different times to one another. The owners of mills and factories found that they could do little to prevent their workers from taking the wakes week off - they would simply not turn up for work. Mill Owners could hardly complain, as they were not overly-generous with holiday entitlement.

by Nick Harling

In Blackburn As It Is, Peter Whittle described the fair of 1849 in great detail:

'We are sure the good folks of Blackburn have lacked nothing at the late fair which could administer to the annual enjoyment of life. The fair drew together a numerous assemblage of shows, altogether comprising a strange medley of things, both animate and inanimate. There was to be seen the big-headed girl, rabbit-eyed children, and a lady giantess. Also panoramic representations of the most conflicting actions which have taken place in China and India'

Added to these were performing birds and a box pavillion where the noble art of self-defence was taught in six easy lessons. Ring tossing, pop-gun shooting for nuts, high-fly swinging, and sword swallowing, not forgetting beer-swilling, for which purpose it was to be purchased 'in every hole and corner that could be made available for the placing of a beer cask'

Nuts, oranges, sheep's trotters, toffee, ginger-bread and toy stalls were likewise abundant, many of them fitted up with false lottery boxes, wheels of fortune, and other contrivances to suit the tastes of a gullible multitude. Fiddles sent forth their squalling notes from the apertures of the public-houses and beer-shops, where fantastic-toed ladies and gentlemen delighted to luxuriate in the mazy dance'

We hope the fair may indeed have served some good purpose 'It has certainly furnished a pretext for the out-burst of annual excitement which is seized upon with such unabated gusto by a large portion of the humbler classes.'

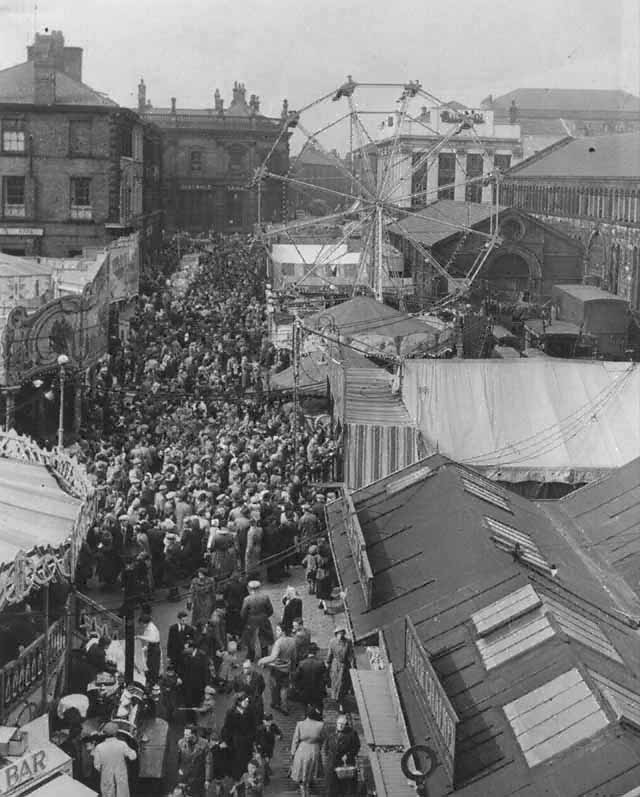

As can be seen, the concept of an agricultural fair or show had by now been eclipsed by pure entertainment for the industrial working class population of the town. By 1852, the venue had moved to the New Market Square, where it remained until well into the 1960s, its character having changed little over the intervening century, bar the addition of more advanced mechanical rides.

By Nick Harling

'The fair’s here!’ How those words transformed the prospect of a visit to town, no longer a dreary chore following your parents round as they did their weekend shopping. Even if it wasn’t open yet, even if the stalls were still being set up, the rides assembled, even if you couldn’t go till Easter Day, just it being there, just a glimpse of the bright wagons and exciting paraphernalia in dull old Market Square brought excitement, new horizons, a touch of the exotic.

And when you did go at last, when it was all up and running, when the generators were chugging and the music was reverberating, when the smells of fried onions were vying with the scent of candy floss - what wonders, what adventures, what magic. There was so much – the rides, sedate horses for the young ones; the dodgems; the waltzer for the teenagers, a blur of girls’ faces distorted by screams; the helter-skelter; the wheel with its human cargo, legs dangling, silhouetted against the sky, and then all the stalls.

There were those with rows of goldfish bowls and if you could get a ping-pong ball in one, you’d win a gold-fish in a plastic bag. There was hoop-la and the coconut shy. There was one with plastic ducks, hook one and it would have a number underneath which corresponded to a prize, never alas one of the train sets or gorgeous dolls on display, but a chalk ornament, or a packet of sweets. There were rifle ranges where demobbed soldiers would aim at ping-pong balls dancing on jets of water, and the less ambitious would shoot at tin men. Three down and you got a prize – the ubiquitous chalk ornament, more likely than not.

There were amusement arcades with penny in the slot machines and those with cranes suspended over an array of prizes: soft toys, watches, jewellery, a 10 bob note in a plastic tube. You could manoeuvre the crane over the chosen prize, lower it and make a grab. Sometimes a precious gift would be secured and you’d inch the crane towards the chute that would deposit it into your hands, but always; always, the gift slipped from the crane’s grasp at the last minute.

There were stalls selling toffee apples, brandy snap, candy floss. There were stalls selling hamburgers, hot dogs and chips. There were stalls selling ice cream and milk shakes and pop. You could buy sweets, novelties made out of rock, pop corn, slabs of toffee. You could buy toys – red Indian outfits, cowboy outfits, bows and arrows, pop-guns, all guaranteed to last until the fair had left town.

And then your parents would say it was time to go, or that they were spent up. And as the sky was growing darker the crowds leaving would be replaced by older teenagers arriving, young men with quiffs and drain-pipe trousers, young women with beehive hair dos and white stilettos. There would be a hint of glamour and danger in the air.

The sounds of the fair would fade as you climbed up the hill out of town. Next day or the day after it would be gone and Market Square would be as dull as ever – until the next time!

An interesting aside was an attempt in the 1890s to abolish the Easter Fair altogether. Generally, fair periods were disliked by millowners who resented having holidays imposed upon them. They were keen to make Easter the main official holiday period in Blackburn, a time when the employees would travel away from the town for a whole week, and the mills would close down for that period. The fair encouraged workers to stay in Blackburn, but still absenting themselves from work for a couple of days. In 1890, the council (largely consisting of millowners) voted to ban the fair from the Market Square. However, the fair organisers simply arranged an alternative venue on the outskirts of town. Within three years, the council capitulated and allowed the fair to return to its original location - by this time, many shop owners had realised that they would lose a significant amount of trade if the fair remained out of town.

Blackburn's Easter Fair is now held in Witton Park, having been ousted from the Market Square yet again by the extensive town-centre redevelopments of the late 1960s.

By Nick Harling

It was the one week in all the year when you could escape the drudgery of Cotton Town. A week when new horizons opened up, a week when you glimpsed how different life could be, when you glimpsed what life was like for the wealthy and privileged. It was the holiday week, Wakes week.

For many it meant a week at the seaside: golden sands, the wide blue sea, the cry of seagulls, the stalls, the smell of fried fish, the rides. It was the coming of the railways that made it possible to transport holidaymakers in their thousands to the Lancashire resorts of Blackpool, Morecambe, Lytham and the newly created St Annes. Lancashire had the most sophisticated railway system in the country in the mid- Victorian period on the 19th century.

It would be an early start to pack cases and make the house secure. One man carefully turned the water off in his cellar before leaving for the week, not realising he'd turned the water off for the whole street. There'd be long queues at the railway station, long queues at the bus station. Engines would be letting off steam, guards slamming doors and blowing whistles, bus drivers carefully counting passengers as they boarded. And then they'd be off.

In the early days the Lancashire resorts were the main destinations, but later Whitby, Scarborough, Bridlington and the resorts of north Wales became popular. For children, and for adults too if the truth be known, there'd be the excitement of being the first to spot the sea. On arriving there'd be the frustrating delay as the trains emptied and people shuffled with heavy cases to the exit. There'd be a walk to the 'digs,' few people could afford taxis. There'd be the formidable landlady who'd point out the do's and don't's, reinforced by notices on the walls forbidding any kind of pleasurable activity and pointing out that 'guests' must leave the premises at 9.00 a.m.and would not be readmitted until 5.00 p.m. And then at last the chance to get to the sea. There it is shining at the end of the street! Children would be tugging their parents along. The beach, the beach - the golden sand; the waves, the donkeys, Punch and Judy, sunshine, candyfloss, toffee-apples, ice cream! What more could anyone wish for, except that it should go on for ever and not just for one week.

back to top

During the 1950s, it became evident that Blackburn town centre was set to undergo change involving large-scale clearance. But the drive to create a new and better town centre threatened the location of the town's traditional Easter Fair. Consequently, in 1960 the late Peter Worden, a member of Blackburn Arts Club, initiated the filming and recording for posterity of Blackburn's Easter Fair, on standard 8mm film. It was decided to theme the film around a boy-meets-girl fairground romance, with Blackburn Arts Club members Sheila Wood and Bob Watkins in starring roles.

Much later, in 2004, Norman Bretherton and Peter Worden undertook a digital reconstruction of the original 8mm film (which may now be lost) and, as Blackburn Archive Films, produced a DVD entitled 'All the Fun..', which included the original 1960 film, along with various additional bonus material not yet ready for inclusion on Cotton Town.

This film appears on Cotton Town by kind permission of Blackburn Archive Films and Blackburn Arts Club.

This production is protected by copyright, and may be used for private viewing only. It may neither be broadcast in any way, including the internet, nor be copied or reproduced either by film or electronic means, without permission from Blackburn Archive Films.

DW 2017

back to top