Workers Playtime

Sunday was the only rest day permitted to cotton workers and that was for religious rather than recreational reasons. For shop workers the situation was worse; they worked on Sunday as well and from 7.00 am until 11.00pm every other day. Mill owners were aghast when workers campaigned for an early finish on Saturday, convinced it would be the ruin of them. Inevitably the temptation to spend what little leisure time they had in the pub was overwhelming for many.

Gradually the situation improved. Government legislation limited hours and introduced Bank Holidays and recreational opportunities expanded. Football was born as a major spectator sport. Cycling and walking became popular. The potential of the countryside for recreation was beginning to be realised. The phenomenon of 'Wakes Weeks', when mills closed down arrived. Going out to the pictures and the theatre became popular and it is believed that Blackburn had the worlds first purpose-built cinema.

Trams enabled people movement to shop, to travel to work and of course to head out of town on a day off.

It took a long time for some millowners to realise that workers were not simply extensions of the machines, to realise that not only did they need time to recover physically from their labour, but that they needed time for recreation. Pubs were the first to cater for this need, but later came organised sport, the music hall, excursions on the canal, excursions on the railway, public concerts and the cinema.

In the 1840s hours at the cotton mill were from 6.00 in the morning until 5.30 at night, with half an hour for breakfast and one hour for lunch. It was a six day week. Six days a week came the dreaded tattoo on the bedroom window as the knocker-up did his rounds with his long pole. Six days a week you had to get out of your bed at 5.00 in the morning, get dressed in the cold and dark and turn out into the street to join the huddled mass tramping the cobbles in silence towards the brightly lit mill. Six days a week you'd enter the weaving shed and hear a lone loom start up, thrashing away in the corner, then another would join it and then another, until the whole shed was aroar with a monstrous din; the legacy of industrialisation, a din that would be ringing in your ears long after you’d left the place almost 12 hours later.

Working conditions for shop workers may have been less harsh, but the hours were longer. It was 7.00 in the morning until 11.00 at night, and 7.00 until noon on Sunday. Often a shop owner wouldn’t shut until his competitors did, and he would send an assistant out to make sure.

There were no holidays with pay and the only public holidays were Good Friday and Christmas Day. This was the real legacy of the Industrial Revolution: machines didn't need a holiday, machines didn't need a rest and the Factory System came as close as it could to making the operatives follow suit. The legacy is still with us today, bank holidays are grudgingly given, working hours are creeping up.

It was all so different in the 18th century. The Bank of England enjoyed 47 days off a year. All saints' days were holidays and handloom weavers would often have Monday and Tuesday off, and the day when they took their finished piece to the 'putter-out' was something of a holiday, a break from the routine and the chance to see something of the wider world.

Manchester man William Marsden began a campaign for an early finish on Saturdays in the 1840s. It was stoutly resisted by mill owners, horrified at the thought of machinery lying idle. The campaign succeeded and Manchester operatives were the first to finish at noon on Saturday.

The Factory Act of 1850 prohibited the employment of women and children after 2.00 pm on Saturdays. Reluctantly the mill owners gave way and men too were granted the same privilege. The situation for shop workers however didn't improve until the 1880s when shop owners finally granted an early finish during the week, on Thursday in Blackburn and Tuesday in Darwen.

In 1847 an act was passed to reduce mill hours to ten a day, though not all mill owners took any notice of it. The 1871 Bank Holiday Act introduced the concept of holidays with pay and created holidays on Boxing Day, Easter Monday, Whit Monday and on the first Monday in August.

It was the arrival of mass forms of cheap transport that gave a boost to the demand for shorter working hours and longer holidays: the railways and to a lesser extent the bicycle. Although it was the mill owners who were primarily reluctant to grant more time off work, the authorities too were alarmed. What would the workers do, apart from spend more time in the pubs and become more of a nuisance? At least if they were locked up in the mills, they were out of the way all day.

Cheap excursions on the railways could carry thousands to the seaside or to the races. Owning a bike meant you could get out into the countryside. And of course providing refreshment and accommodation for these early holiday-makers was a new industry in itself. The tourist industry was born and the pressure to create more leisure and more money-making opportunities was on.

On 30th June 1906, the Spring Bridge at Whitewell collapsed. Two groups from Preston and Todmorden were enjoying a day out , when disaster struck.

Two local newspapers reported the incident. Interestingly the emphasis is different :the Northern Daily Telegraph failed to mention the party from Preston.

Blackburn photographer A.E. Shaw recorded the scene for posterity.

A DIP IN THE HODDER.

STARTLING COLLAPSE OF BRIDGE.

PICNIC PARTY DROPPED INTO THE RIVER.

The officials of the Todmorden Corporation, on the occasion of their annual outing to Whitewell on Saturday, had an exciting experience which might very easily have ended seriously. The party numbered 34, and having just been photographed three of them went to bathe in the River Hodder. The others collected on a footbridge about 35 yards long made of wood, supported by iron girders, and protected by railings. Without any warning the bridge suddenly broke in at least two places, and fell into the water. About a score of picnickers, including some from Nelson and Colne, were precipitated into the river, but happily it was not so deep where the majority fell, and they managed to scramble out.

Mr. James Heap, the Todmorden borough surveyor was not so fortunate, being thrown into a part of the river seven feet deep, and he had to swim to save his life. Had he not been able to swim he would probably have been drowned. Mr James Whitehead, educational clerk; Mr Fred Rogers, sanitary inspector; Mr G. W. Jackman, assistant surveyor; Mr Thomas Woodhead, attendance officer, and many others were submerged and more or less injured.

Mr Sam Cliffe, veterinary surgeon, suffered worst of all. He was standing at the end of the bridge, and when it collapsed his end jumped and threw him into the riverbed, a fall of twelve feet. Huge coping stones fell on top of him, and he was wedged fast by an iron girder. The wonder was he escaped alive. As speedily as possible he was extricated, and found to have sustained some nasty bruises and severely sprained himself. When seen last night Mr Cliffe was confined to his room,and complained much of his injuries.

From The Northern Daily Telegraph Monday 2nd July 1906

An alarming accident occurred near the Whitewell Hotel about five o clock on Saturday afternoon. A party of Preston and Todmorden gentlemen numbering about 30 were standing on the swing bridge which crosses the Hodder at this point watching some men bathe, when suddenly the bridge left its support on one side of the bank, and the structure collapsed into the river.

About 20 were precipitated a distance of 20ft into the river, which was fairly low at the time. Fortunately all escaped without serious injuries though the ducking which they received made matters very uncomfortable. On Sunday scores of people in the district visited the scene of the accident.

The party from Preston, writes an eye-witness, was composed of a number of overlookers employed at Messrs Horrockses, Crewdson, and Co.’s mills who were on their annual trip. They visited the suspension bridge, and it was the sudden weight of about 50 men being transferred from one side of the bridge to the other which caused the structure to collapse.

About 40 of those on the bridge were thrown into the water, which was about 5 foot deep. There were several exciting rescues. The majority clung to the wrecked bridge and “scammered” or climbed to he side which remained intact.

There was one amusing incident. One of the party was taking a snapshot of the Fishwick Mill overlookers at the time, and he was thrown head foremost into the water, his camera being lost to view.Several of the men were taken to Longridge Station returning on the nine o'clock train.

The party from Todmorden were Officials of the Coporation, who were on their annual outing.

Mr James Heap, the Todmorden borough surveyor, was thrown into a part of the river which was 7ft deep. He had to swim to save his life and he lost his gold eyeglass. Mr Sam Cliffe, veterinary surgeon, who was standing at the end of the bridge when it collapsed, was thrown onto the river bed, a fall of 12ft., and a coping stone fell on top of him. He was wedged fast by an iron girder, and when extricated was found to have suffered some nasty bruises and sprains.

Nearly all the party were bruised more or less and it is considered to have been through very good luck that nobody was injured seriously or killed. One or two remarkable rescues were made. An overlooker name Duxbury was rescued by one of his comrades named Southworth, from a very perilous position.

In some spots the water was eight feet deep and several of the party plumped into the water over-head. In one or two cases the men fell on the top of one another and the position of the nethermost man was not a happy one.

From The Blackburn Times Saturday 7 July 1906

Holiday destinations 100 years ago were surprisingly adventurous. Thomas Cook advertising in the Blackburn Times offered tours of the Thuringian Alps, the Dolomites, Norway, and even trips round the world. Adverts for more local destinations proliferated however: Blackpool, Southport, North Wales, Northern Ireland figured prominently. Morecambe was a popular spot and a typical advert is that of the Misses Taylor offering 'assured home comforts' at Earnsdale House on Alexandre Road in Morecambe.

Morecambe, originally Poulton-le Sands, started life as a railway terminal and port, rivalling Glasson in the amount of goods handled. The port's business declined, but the coming of the railway launched it as a holiday resort and a guide-book published in 1881 described it as 'a clean, healthy watering place... with numerous well-appointed shops, hotels, inns and lodging housese for the reception and accommodation of visitors and tourists, for whose use there is a large supply of vehicles and pleasure boats.'

A guide to the Morecambe Bay area was just one of the many titles in a list of town and tourist guides available from Blackburn Library. Librarian Richard Ashton had compiled the list and it appeared in the Blackburn Times of July 29th 1905, with an editorial warning that a major cause of holiday disappointment arose because people did not do their 'homework,' did not read up on their destinations before setting off.

St Annes was in prospect for the children of Bent Street Ragged School. The Blackburn Times reported that the staggering figure of 1250 of them from the most deprived areas of the town were to be taken to Lancashire's most genteel resort for the day. The cost per child was 10p and the paper appealed for donations.

St Annes was conjured up out of nothing, out of nowhere. Elijah Hargreaves, a successful entrepreneur from Rossendale, explored the sandhills beyond Lytham and had a vision of a new resort. He raised money among his fellow business men in East Lancashire and on March 31st 1875 the foundation stone of the St Annes Hotel was laid near to the railway station. St Annes became a favoured retirement place for the well-to-do. Many of Blackburn's prominent citizens bought villas there. You can imagine their faces as they strolled along the gracious promenades when the tide of urchins from Bent Street Ragged School swept towards them.

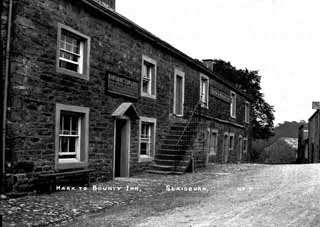

The seaside didn't have it all its own way; there were attractions inland as well. The Ribble Valley and the Dales boasted popular resorts. Clark's Temperance Hotel in Malham promised comfortable beds with conveyances to meet parties at Hellifield Station. The Assembly Rooms at Waddington offered good stabling, dancing, use of piano and private apartments.

One hundred years earlier the idea of the countryside as suitable for recreation and leisure would have seemed strange to most people. Moors and mountains and wild places were regarded with horror. The countryside was where they lived and worked: a visit to the town would have had more attractions. The romantic movement in art and literature created an interest in nature. William Wordsworth in particular evoked rural idylls, but it was the horrors of industrialisation that created an appreciation of fresh air and fine views. Any opportunity to escape the grim, gridirons of terraced housing with their menacing mills was to be seized upon.

Many people today have three or four weeks holiday or even more. Many will go abroad twice a year and have several weekends away, 100 years ago it was just one week. One week was all they had to glimpse what their lives could have been like if they'd been born into more fortunate circumstances; one week to rest and reflect and let the impressions of sea and countryside sink in. How vivid and vital that week must have been. How it must have flown. Picture them at the edge of the sea on the evening of the last day watching the sun go down, casting its crimson glitter, already beneath the crashing waves, they could hear the roar of the looms, the sound that would soon be ringing in their ears day and night, a sound they couldn't hope to escape from for another year.