Just Jessica...

The reference library in the old Blackburn Library in Library Street was a solemn and sombre place. The sun never shone there and no voice was ever raised above a whisper. There was a monastic atmosphere and as a novice librarian I carried out my duties in a suitably reverent manner.

All that changed when Jessica Lofthouse appeared. The door would fly open and she would be there: a magnificent presence in flamboyant colours, twice as large as life, and life was pretty large in her case. She was without a scrap of self-consciousness and proclaimed her requirements in a loud voice.

I was more than a little overawed by her, but enthralled as well and looked forward to her visits as you look forward to the visits of a heavenly body. Sadly Jessica died in 1988. Many of her personal papers were passed on to the library and I was privileged to be able to peruse them and gain an insight into her character. I was even more privileged to be asked to write about her for Cotton Town. Jessica deserves a full-length biography by a more capable hand than mine, but I am honoured to have had the opportunity to create this small memorial to her.

"Today is October 20th in the year of our lord 1925. In three weeks I will be seventeen which is frightfully old, - seventeen seems infinitely older than sixteen, but still I don't think I have felt any different while I have been sixteen than when I was fifteen. This morning I fainted for the first time in my life and I have never felt so silly before"

This was the first entry in a diary kept by Jessica Lofthouse. At the time she was living at 126 Montague St in Blackburn with her parents and stepsister Annie. She was a prefect in the sixth form at Blakey Moor Central School. Her career as a writer had already begun. At the age of eleven her stories had appeared in the children's column of the Blackburn Times. When she was thirteen her historical story of the rebellion of Wat Tyler ran in the Liverpool Weekly Post for several months and she received her first payment.

She describes herself in her diary:

"I am nearly 5ft 4 inches from the ground and weigh 7 stones 10lbs. My hair, my only beauty is a gold - red - brown, sometimes one and sometimes all at once - otherwise copper or auburn, my eyes are dark brown and far apart (memory), my forehead is broad (brains), my nose is straight (like daddy's), my mouth is large, top lip short and curved, chin sensitive etc etc"

Her birth certificate records that Jessica was born on the 8th of November 1906 at 12 Wilson St, Clitheroe. Jessica notes in her diary however that there is some uncertainty as to the date: she was born so close to midnight on the 8th that the real date might be the 9th. This is something she refers to more than once in diary entries on her birthday.

Her father John was a grocer. He had been born in Appletreewick in Yorkshire in 1868. His own father, also John had been born in Bolton-By-Bowland, where he had been the village policeman. Jessica's mother had been born Jemima Read in Clitheroe in 1869. Her father Richard had also been born in Clitheroe where he was a farrier John had previously been married to Jemima's sister Isabella who died in 1902. He had a daughter Annie by that marriage, Jessica's stepsister.

In 1901 Clitheroe's population was 11,414. Its major industry was cotton, but there were lime and cement works and a paper mill. In 1905 the public library opened. Today Clitheroe is a pleasant urban interlude in the Ribble Valley catering to tourists and daytrippers and providing sought after dormitory accommodation for workers in Blackburn, Burnley and beyond. Two hundred years ago it was a blacker, grimmer place, gas-lit and begrimed with the smoke from factory and domestic chimneys.

Jessica was born in the front bedroom above the grocer's shop. The room had a frieze of blue and gold swallows. It would be a murky November night, cold without and not much cheer to welcome a new baby into the world. Probably they'd lit a fire in the bedroom.

John's shop was an old fashioned grocer's such as does not exist today. Most things would be on sale and most things would have been loose in bins and storage jars ready to be weighed out on the brass scales. There would have been oil and honey and molasses, dry goods such as sugar and flour, tin-boxes of biscuits that would be weighed and sold in paper bags, jars of boiled sweets and sticks of candy. There would have been tins piled up and items of hardware hanging from the ceiling. There would have been donkey stones for the front steps, black lead for the ranges, and big blocks of soap for washing day. A fascinating place for a young girl, but hard work for her parents. Shop hours were long, often they would not close till 11 at night and would be open again by 7 or 8 the next day. Competition was fierce. It was not unknown for a shopkeeper to send a child round to make sure other shops were not still open, before deciding to close.

In 1910 when Jessica was 4, John's business folded and he went to work at Barrow Print Works. The family moved to Brennand St. Jessica started in the infants department of the Council School shortly afterwards. She was terrified of the headmistress whom she later described as being a "tight-corseted, high bone-collared old maid". She had to be bribed to go to school by the promise of sweets. At the age of 7 she graduated to the senior department, where she met Nell, who was to be a life-long friend. This was also the year that the First World War broke out.

She remembered the bands playing at the station as trainloads of volunteers were sent off. Her Uncle Dick was one of the first to volunteer, followed by five of her cousins. She remembered the mournful sound of the trains coming through the night to bring wounded to the asylum at Whalley, which was being used as a military hospital. She remembered being woken in the night by a tremendous explosion that shook the earth. The streets were full and panic was breaking out as people thought the Germans had invaded. Next day they learned that the munitions works at White Lund at Lancaster had exploded.

At the age of 11 Jessica's world was turned upside down. Her father and Annie had been working in Blackburn, travelling there every day by train. In 1917 the family went to live in Blackburn. Jessica describes how she felt in her book 'Three Rivers':

"I am glad mine was a Clitheroe childhood. It was a completely happy one, and the only unhappy day I can remember was the one when my family removed to Blackburn. It was May, and I vividly remember the armful of lilac into which my tears flowed all the way during the train journey."

They lived at 126 Montague St, which was on the right going up opposite Johnstone Street. Clitheroe itself was very much an industrial town at the time, but Blackburn was much more so. When she looked down on the smoke-blackened town, at the rows and rows of terraced houses and the dozens of black-plumed mill chimneys, she must have thought that the leafy lanes of the Ribble Valley were a long way off.

Her new school was Blakey Moor. It was virtually a new school at the time having been opened in July 1911. Mr Caithness from Scotland was the headmaster. He taught Jessica astronomy. She was in school on November 11th 1918 when their lesson was interrupted by loud cheering and Mr Caithness came in to tell them that the armistice had been signed. Although it was only Monday the school was closed for the week. Flags were flying, horns sounding, fireworks were being set off. The streets of Blackburn were crowded. Pubs were open day and night. It was a week of celebration. She was one of the crowd in Corporation Park on 21st August 1924 when the war memorial was unveiled.

Jessica did well at school. She was a prefect, editor of the school magazine, house captain and head girl. In 1923 her school certificate results were the best in the school. In that year she won subject prizes in 4 subjects and on the 16th of November went to the bookshop to choose them. She describes the experience in her diary:

"We went the four of us to Seed and Gabbutt's at four o clock to choose our prizes. I felt like 'Jack among the maidens sweetly teased'. All the books were so beautiful I'd have liked all of them. After much deliberation I finally chose two little red leather volumes of Browning and a glorious, antique brown leather volume of Tennyson's poems. I'll have to pay 1/- extra. I'm quite satisfied with my selection."

Jessica returned to Clitheroe at every opportunity. She had relatives there and spent most of her holidays exploring the valley of the Ribble from the larch woods of Stainforth to the heather moors of Mellor. She knew it in all seasons; summer sunshine and bleak mid-Winter. Her eye had learnt to seek out beauty in less promising circumstances, even in Blackburn. Here she describes the view of Johnstone Street from the bedroom window:

"The street, from the uneven cobbles to where chimney and sky met, was entirely transfigured. It had rained heavily and now the sun shone making the dripping street one mass of silver, dazzling, twinkling silver and the roofs were draped in silver tissue. From the summit of each chimney burnt a silver flame. Yet in that street were people, workers with unlovely souls, work-hardened, who with bent heads saw nothing of the beauty. Oh! If I ever become a teacher I will try to bring beauty into the souls of the children of these workers."

We have to remember that this is a 17 year old schoolgirl speaking and yet despite the naivety, this passage reveals a lot about Jessica Lofthouse. She saw the beauty in the world around her and she wanted to make others see it. Later on in her life she would do this by writing books, but first of all she intended to do so by teaching.

On September 24th 1925 Jessica went to London to train to be a teacher at Whitelands College in Chelsea. She had won the Henry Lewis Training College Scholarship, which was worth £30 a year. She expected to be homesick, but was far too busy for that. As well as her studies, she took full advantage of being in London, visiting the Tate and National galleries, walking along the Embankment and the Mall, shopping in Oxford St and Knightsbridge. She had tea at Lyons Corner Houses, went to plays at the Old Vic and the pictures at the Marble Arch Pavilion. She made many friends, but Ena Hughes from North Wales, her father was Mayor of Flint, was her special companion. This is how she describes her in her diary:

". . . a friend to confide in. Never before have I had a confidante, I have kept my thoughts within me. Now when we sit on the bed at night before lights out, or walk hand in hand round the quadrangle before dorm bell goes we talk of many intimate things, on life and people. Ena is far more experienced than I am, I call her sophisticated."

School practice loomed in 1926. Jessica had been apprehensive about this, but in the event all went well. She did an extra year at King's College, despite the misgivings of her father, mainly on financial grounds, and took up her first post at Anfield Rd Boy's School in Liverpool teaching art, living at 141 Stanley Park Avenue.

In April 1928 she saw her first talking picture: 'The Singing Fool' with Al Johnson. This is her reaction:

"In spite of vile accent, worse voices and certain crudities I enjoyed it. The silent film is doomed to a slow but inevitable death I think."

She gave up her diaries for a while, but by 1930 was writing them again. Here is her review of the year:

"What have been my happiest memories of 1930. My mind. . . flies instantly to the country - last Spring, the loveliest ever and the glory of trees, the new walk Louise and I discovered from Whalley Nab to Cock Bridge - the desolation and solitariness of Pendle summit disturbed only by the curlews' cries. . . . June with roses in the hedgerows. . . . Mearley Woods with the sunlight filtering through the bronze of the beech trees."

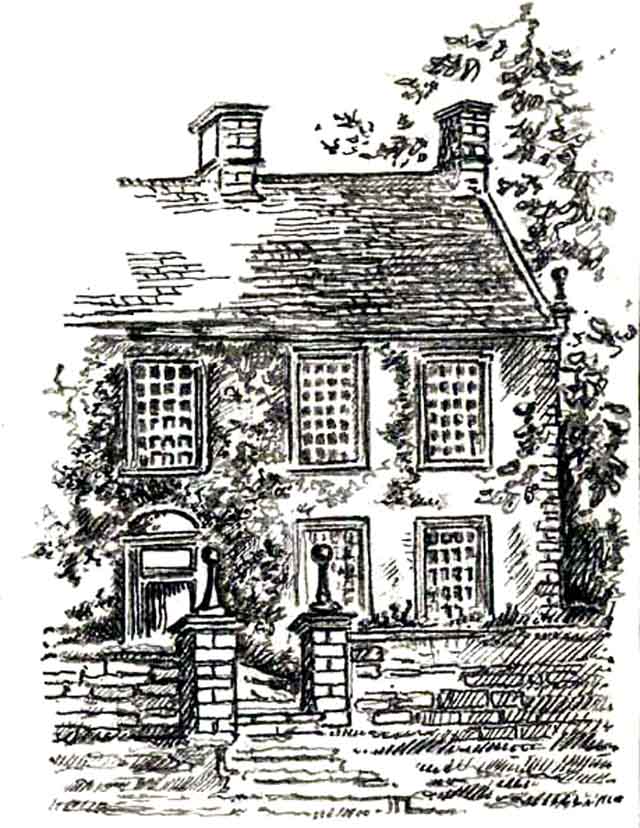

Drawing of Whitendale by Jessica Lofthouse

And of the holiday she spent in Belgium that year:

"Bruges which kept her medieval dignity in spite of her tourists, a city of great beauty - Brussels at night with the Boulevards all alight - soldiers marching through the Place Leopold I in Namur where the Huns once marched and I tried to acquire the taste for biere and failed- so many experiences where places and sights delighted me but a year without any emotional outlet."

A year later she was exploring the countryside by car. Annie and her drove down to Shrewsbury and then off into Wales. Ominous knocking and oil loss meant frequent stops at garages, but there was some beautiful scenery to admire. She recorded in her diary however that while motoring was 'grand', it couldn't rival walking.

Jessica's mother Jemima died on 7th October 1936 at 5.30 in the morning. She notes in her diary:

"The end came as she sat up early in the morning. I opened the window."

On March 4th 1938 Jessica began a series of articles on the North of England in the Blackburn Times, illustrated by her own pen and ink sketches. It was her intention to draw readers' attention to what she regarded as some of the loveliest scenery in England and to point out any historical significance. By then Jessica and her family were living at Scot-Laithe, Livesey Branch Road, Feniscowles.

When the Second World War broke out Jessica was still working in Liverpool and coming home to Blackburn at the weekend. On a Sunday at the end of January 1940 blizzards brought the country to a standstill. Drifts up to ten feet high made it impossible for her to even get to the station. It wasn't until Thursday of that week that a train got through to Liverpool. Now her diaries record her walks in the Ribble Valley alongside notes on the war's progress:

May 31st 1940 "Battle of Dunkirk beaches - glorious day. Mist early. Very warm. Walk from Brungerley by Cop Law."

Being a writer in wartime had its advantages and difficulties. There was an eager audience for writing of all kinds, particularly that which would remind readers of happier times; of walks in the countryside and of the enduring nature of English history. On the other hand there was an acute shortage of paper. However it was during the war and in the immediate pre war years that Jessica's professional writing career began.

In 1938 Jessica's first book appeared, "The Rediscovery of the North." It was a self publishing venture, printed by the Blackburn Times and was a collection of the articles she had had published in that paper; a collection of 'explorations on foot and by car.' It may seem obvious to us now that there's much beautiful countryside to explore in the North, but it was less so then.

As a result of her book and her articles which continued to appear in the Blackburn Times, Jessica began her lecturing career, which was to last to the end of her life. She gave talks to teachers, army units and the WEA. She also began leading walks for the YHA and other groups. Her articles also inspired many soldiers serving overseas to write in appreciation of the reminder of England that they provided.

At this time she was also a teacher of art and local history at Bangor Street Secondary Modern School. She was well liked by her pupils and used to take them on days out to local beauty spots such as Pendle Hill.

In 1943 the Brian Vesey-Fitzgerald, the general editor of publisher Robert Hale's County Series wrote to Blackburn author Dorothy Whipple proposing that she write the Lancashire volume for the series. At the time Dorothy was living in Kettering. She had met Jessica in Blackburn, her husband Alfred having been Director of Education for Blackburn. For some time Jessica had been trying to interest publishers in her latest book 'Three Rivers.' Dorothy did not wish to write the book and had already had sight of 'Three Rivers' when one of the directors of Dent's sent it to her. She advised Jessica to contact Robert Hale.

In a letter dated 12th October 1944 Hale's wrote to Jessica informing her that their readers' reports were favourable but that some revision and 'polishing' was required. By February 1945 they were writing to offer terms: £50 advance, 10% on first 1500 copies, 15% on next 3500 etc. There were delays caused by paper shortages, but 'Three Rivers' was published on 16th August 1946. The book was well reviewed in the national and local press and sold well. Jessica received many enthusiastic letters from readers. By now her second book 'Off to the Lakes' had been accepted and was in production.

Drawing of Higher Lee near Abbeystead by Jessica Lofthouse

The BBC in Manchester asked Jessica to appear on their Northern Bookshelf programme. In her diary she recorded that she felt more nervous about this than any of her lectures. The day of the broadcast was 14th of October 1946. She describes it thus:

"The day at last. . . . arrived at the BBC by taxi at 9.30 pm . . . the studio - a small austere one full of boxes, things with knobs on and ear phones hanging and a table with the microphone - an innocent wire meshed object which never gave me the feeling of being a link with the outside world. But my knees dithered and I feared my teeth would chatter . . .the seconds finger moved on to 10.30 - a light flashed . . . my first sentence seemed very strange to me but after the opening I became easier. Finished with 25 seconds to spare."

Friends throughout the country had been listening in and she received many congratulations and the Blackburn Times said:

"Miss Lofthouse seemed to enjoy her interview thoroughly. . . There was no mistaking Miss Lofthouse's voice in a short but most enjoyable broadcast."

On 26th August 1946 Jessica took up her post at St Hilda's. 1946 was a good year for Jessica, however it ended with an unfortunate accident. Alighting from the Feniscowles bus on Thursday November 1st, she slipped and sprained her ankle. Anne phoned for Dr Walmsley who ordered her off to the Infirmary for an X ray - nothing broken, but for a keen walker and for someone with a full programme of lectures ahead of her, it was bad news indeed. Jessica was not able to resume walking again until the following spring.

In January 1947 she began work on a children's novel: 'Cumber Enders'. She was working on it in February when the great snowfall began. By the 6th roads across the Pennines were blocked. By the 8th it had been decided to shut down nearly all industry to conserve electricity supplies for homes. There was a blackout at night made more hazardous by the slippery conditions underfoot. At St Hilda's they were down to their last shovel full of coke. By St Valentine's Day newspapers were back to their wartime format, monthly magazines were cancelled, the Radio Times was suspended, radio programmes curtailed. Jessica spent the day typing her novel. She wrote in her diary:

"All lights are out - like a blackout in wartime. I looked out of the window tonight - not a lamp, not a light - a wind howling and black as pitch."

The worst blizzards came later in the month on the 25th. St Hilda's closed and Jessica was able to get on with her novel. The thaw came at last in March. Jessica submitted her novel to Robert Hale and by August 14th they were replying with readers' reports that were less than enthusiastic. Although they encouraged her to undertake revision of her novel, she did not do so and it was never published.

Despite an enjoyable holiday in Ireland 1950 was not a good year Jessica's sister Anne had to have an operation for a detached retina and her father's health deteriorated. On 28th June she wrote:

"Too desperately unhappy to carry on with diary entries during the next few months."

There are no further entries until December.

On March 27th 1951 her father died at the age of 83. He had been captain of Clitheroe Cycle Club and bell ringer at the cathedral. In many ways Jessica never kept a diary again in quite the same way. She records walks and weather and practical matters, but we don't get the same insights into her feelings and thoughts. In 1956 she moved to Low Hollins in York Lane Langho, nearer her beloved Clitheroe.

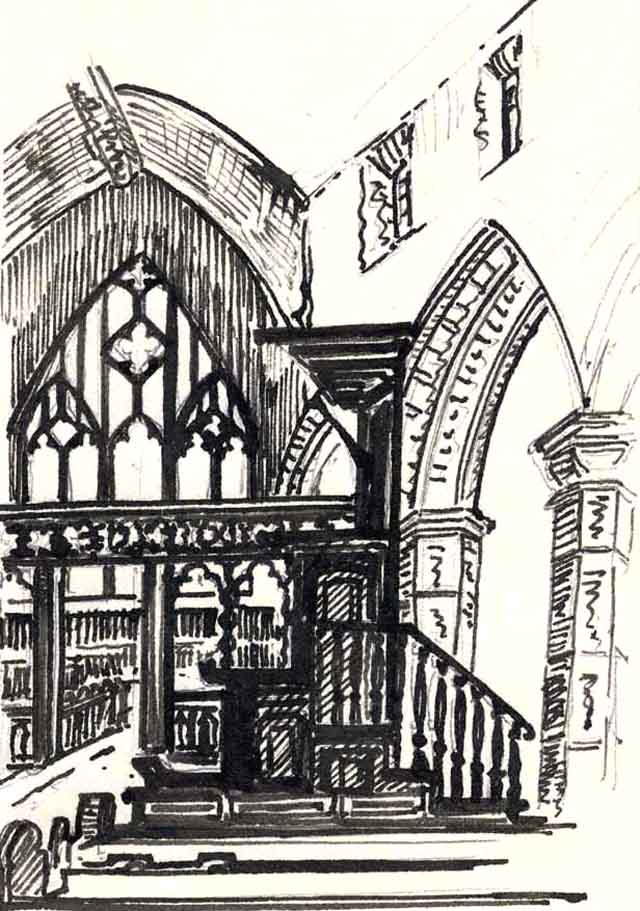

Drawing of Church interior by Jessica Lofthouse

Over the next few years Jessica grew into the figure that many people in Lancashire and beyond will remember: larger than life, slightly flamboyant, slightly eccentric. Her books continued to be published and reprinted. Her articles continued to appear and she was in great demand to give talks and lead walks. Anne died on 13th Feb. 1980.

In addition to her holidays and excursions in the UK, Jessica travelled abroad extensively, visiting Austria, Italy, Norway, Sweden, Yugoslavia, the United States, Israel and within a few weeks of her death, Australia.

She died on Thursday 31st March 1988 after a short illness in Clitheroe hospital. She had over 20 books published, hundreds of articles and must have communicated her love of nature and the beauty on the North of England to many thousands. It might be appropriate to end with a diary entry from her more carefree times from April 1927 when she was in the springtime of her own life:

"On Tuesday Louise and I had a long day walking, on the hills all the way from Wilpshire to Wiswell. The day was ideal for the sun continued to shine with April brilliance and a boisterous westerly wind was at our back. Great cloud shadows fleeing over the whole landscape at one moment covered the valley in gloom and driven on by the wind cast on the hilltops patches of darkness when the valley meadows glowed pale gold again in the sunlight. Never have I heard the skylarks carol so gaily . . .

" . . . the moors looked so bald and brown around us with the tufts of burnt heather, the sky was so blue behind the fleeting clouds and beyond the peaceful valley the hills rose gradually in blues, greys and golds of many hues. At every few steps I had to stop and survey the scene again. I loved it so. With York village left behind us Pendle confronted us, a lion still sleeping with the sun playing upon its flanks. Dear old Pendle. And in the valley far ahead I saw Clitheroe's grey castle crag again. Here was the whole countryside before us."

Unless stated, the images used in this article may not directly be connected to Jessica Lofthouse.

Jessica would have loved it. The great open spaces of the American west were on her scale. The privations and perils of the wagon train would not have daunted her. She would have been at the head of the column, urging on her horses, her keen eye scanning the far horizon for the next adventure. But she missed it. Her grandfather John Lofthouse emigrated to the United States, but her grandmother Margaret wouldn't go. She stayed in Clitheroe with Jessica's father John and died there in 1896.

Joseph moved to Clitheroe and worked in a cotton mill. His father died in 1847 and in 1853 he emigrated, sailing on the 'Elvira Owen' from Liverpool to New Orleans. He drove an ox team crossing the plains to Salt Lake City. He married Charlotte Elizabeth Woodhead in 1856 and the family endured many hardships before settling in Paradise in 1868 where he died.

This latest information has come to light as a result of the research of Maria Kingston, herself a Lofthouse, pictured above. Her great great grandfather was Jessica's grandfather. Maria has established that the Lofthouses originated in the village of the same name near Ripon in Yorkshire and were agricultural workers for many generations before moving to Clitheroe.

Jessica herself visited America in 1983. She flew to Los Angeles on 30th April and then took a flight to Salt Lake City, impressed by 'wild, tormented cloud formations.' She visited the Latter Day Saints Library to research the Lofthouse family. A few days later the cap on her front tooth fell out and she had to have recourse to the emergency dental service to get it replaced, which cost her 8 dollars. It was cold still and there was snow on the Ochre Mountains. Snow everywhere on May 11th when blizzards kept her indoors writing postcards. When it cleared, she had a trip to Grantchester to see the early Lofthouse settlements.

She travelled to Brigham City and followed the Mormon Trail to Sweetwater and the Continental Divide. She stayed in Honeyville a guest of Fred Bingham, where she was interviewed by the local paper and described herself as ' the only fully paid-up British spinster, Church of England member, loyal Royalist and member of the Daughters of the Utah Pioneers' at large. There was a family reunion and a barbecue. It was now hot and the evenings were warm

Whit Sunday, Pentecost, arrived. Jessica noted in her diary that the Mormon Church didn’t recognise it. She returned to the Mormon Trail, visited Ruby Welsh who as a child had often stayed with Butch Cassidy’s sister. She travelled by Greyhound Coach through a South Utah plagued with floods to Cedar City. It was hot and the sun turned Cedar Canyon and the mountains into ‘red fire.’

On June 6th Jessica left on the Greyhound for Los Angeles. It was a long, hot journey with few refreshment stops. She stayed with the Coates family in Long Beach and visited the mission at San Luis Rey where Kit Carson had once been stationed along with a battalion of Mormon Volunteers. She visited too the Queen Mary, the famous liner that was now a hotel and restaurant complex.

She flew back to England on June 10th and saw the day dawn over the Arctic touching the snowy seascape with a rosy glow. It was dull and wet in Manchester. The cap on Jessica's tooth had come off again. There was a moment of panic when it seemed her luggage had gone astray, but she'd been waiting for it at the wrong place. When she got home she went to Spar to get some chewing gum to hold her tooth in place