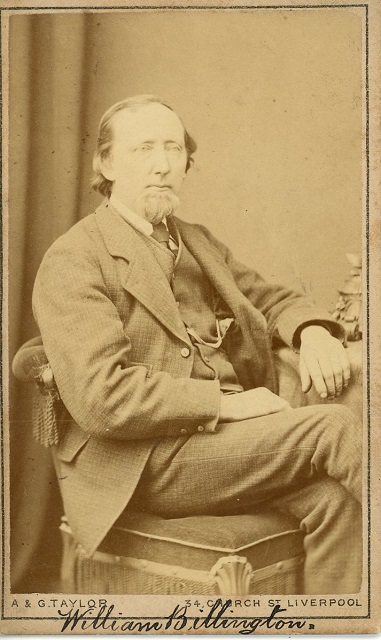

William Billington (1825-84) was born at Samlesbury, his parents being impoverished handloom weavers. He received little formal education, but despite his harsh beginning he became a noted "artizan poet" and, within his lifetime, acquired the epithet, "The Blackburn Poet". Billington is mainly remembered for his popular Lancashire dialect poems "Th' Shurat-weyvur's song" and "Aw wod this war wur ended", both of which deal with the devastating effects of the "Cotton Famine" of the 1860's. He also became a newspaper columnist, writing in The Blackburn Standard and The Blackburn Times on local literary subjects. Billington's poetry was published in two volumes, "Sheen and Shade" (1861) and "Lancashire Songs with other sketches" (1883).

By Ian Petticrew.

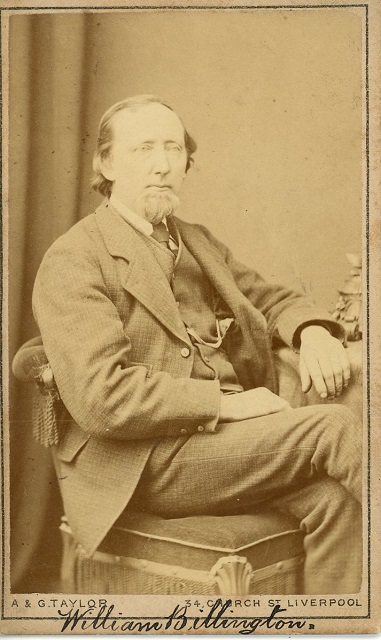

This photograph of William Billington is from Blackburn Library's collection of "Bygone Blackburnians" , collected by D. Geddes:

Blackburn to the Fore! Jamie Holman, Head of Fine Art at Blackburn University College was one of nine artists commisioned by the "Art in Manufacture" project for the first National Festival of Making held in Blackburn, May 6th and 7th, 2017. Jamie was commissioned to work with paper manufacturers, Roach Bridge Tissues; a family run firm with over 170 years of experience of paper manfacture. The resulting artworks and performances were revealed as part of the festival with a solo exhibition, a digital moving image commission and two choral performances in Blackburn Cathedral. The choral performance and exhibitions were inspired by William Billington's poem "Blackburn to the Fore!".

In order to see the specially commissioned performance by Blackburn People's Choir of William Billington's "Blackburn to the Fore", please select the following link, by kind permission of Jamie Holman:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UTziJAFz5x8&t=17s

For Shakespeare and Ben Jonson the Mermaid Tavern was the favoured hostelry and source of inspiration. For Blackburn's bards in the middle of the 19th century it was a beerhouse on the corner of Bradshaw Street and Nab Lane, known as 'Poets' Corner.' Here congregated such luminaries as William Billington, John Baron, John Critchley Prince and Richard Dugdale. In an article in the Blackburn Times of June 23rd 1972 George Miller describes a typical exchange of wit:

Another distinguished rhymster to grace the tavern with his presence was John Critchley Prince. He acquired more than local fame, 'wrote like an angel' but, alas, lived like the Devil, being sadly addicted to the bottle.

It was while presiding at the Blackburn Scotsmen's dinner, held here about 1849, that Prince toasted a fellow poet, Richard Dugdale, known to fame as the 'Bard of Ribblesdale', with the dubious words, 'a fine man, but no poet.' To which witticism Dugdale instantly replied by proposing the health of Prince, 'a fine poet, but no man.'

The work of our dialect poets is not given the attention it merits. Burns and the Border balladeers are accorded their place in literary history, but the likes of Edwin Waugh, Sam Laycock are sadly overlooked. As George Miller remarked: 'Humble and self-taught there is a wholesome quality in the simple verse of these men that we shall seek in vain in the sophisticated products of most contemporary poetry.'

One other who did his utmost to honour their genius was George Hull who published 'The Poets and Poetry of Blackburn' in 1902. It contains biographies and examples of some our best local poets' work, such as this by William Baron:

For an on-line version of George Hull's book, click here.

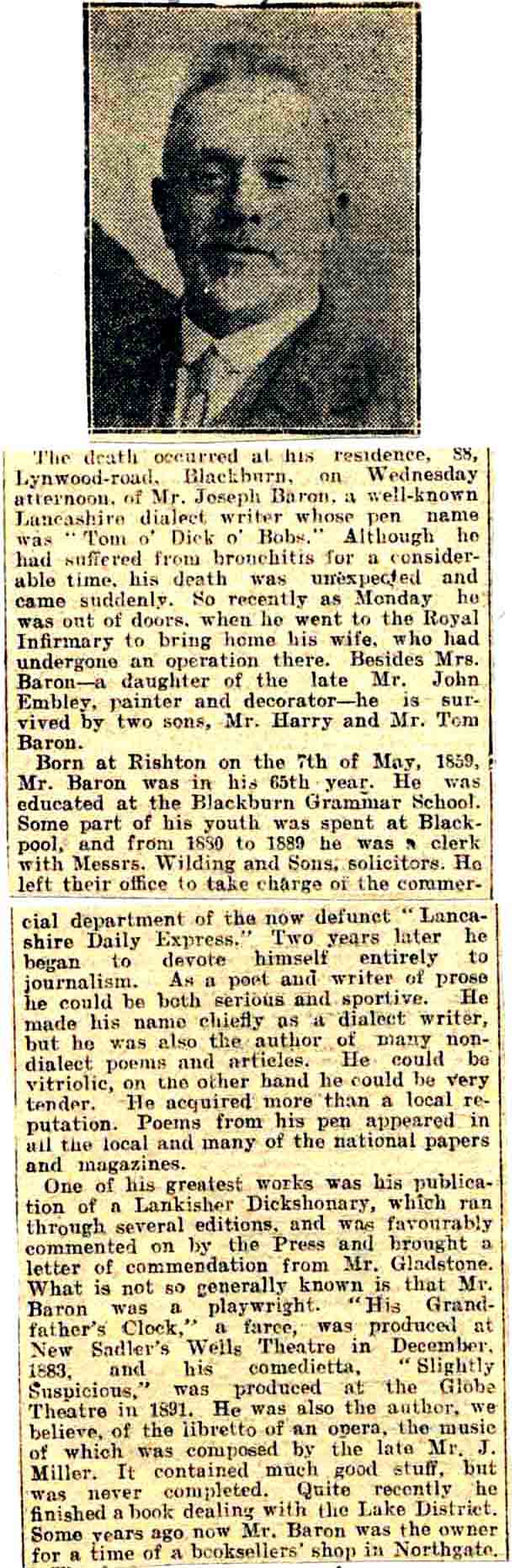

Joseph Baron was a dialect writer, born in Rishton in 1859.He attended Blackburn Grammar School and later worked as a solicitor's clerk. After this he worked in the commercial department of the Lancashire Evening Express, which he left after two years to devote himself entirely to journalism. He is probably most famous for the works "Blegburn Dickshonary" and "Lankisher Dickshonary", in which he listed popular dialect word and phrases form the local area.

This article was taken from the Blackburn Times, March 15th 1924:

Charles Hodgson from Canada contacted Cottontown about the Blegburn Dickshonary. He presents a daily web-based broadcast about interesting words and their derivation. He had seen this work cited in the Oxford English Dictionary and was curious to know more about it.

We were happy to tell him about Joseph Baron and his dialect works.

He was keen to have a derivation of one of Joseph's words read for his website, in an authentic accent. We were happy to oblige, and Diana Rushton read the derivation of the word Baby or Babby.

This is a wonderful thing, an heaw mich wonderful depends on id number. Iv it's th'fost it's a hangel; yo' mezzer id an weigh id every Setterda'neet, an book th' perticklers deawn in a family Bible. An' when id says "Daddy" an' "Mammy"- wey, yo' wodn'd tek th' Nash'nal Det for id. But iv it's th' duzzenth, it's a little imp an' id gets plenty o' strap; aw know abeawt id, becos aw've hed' em - at leeast th'wife hes, an it's o th'same.

The recording of "Babby" was broadcast on Charles's website on 28th October, 2005

Dr Simon Rennie and Dr Ruth Mather are currently working on a project exploring the poetry written during Lancashire's cotton famine. The primary focus concerns the poetry published in local newspapers, particularly in the Blackburn Standard and Blackburn Times.

Further information about the whole project can be found by selecting the following link: Cotton Famine Poetry

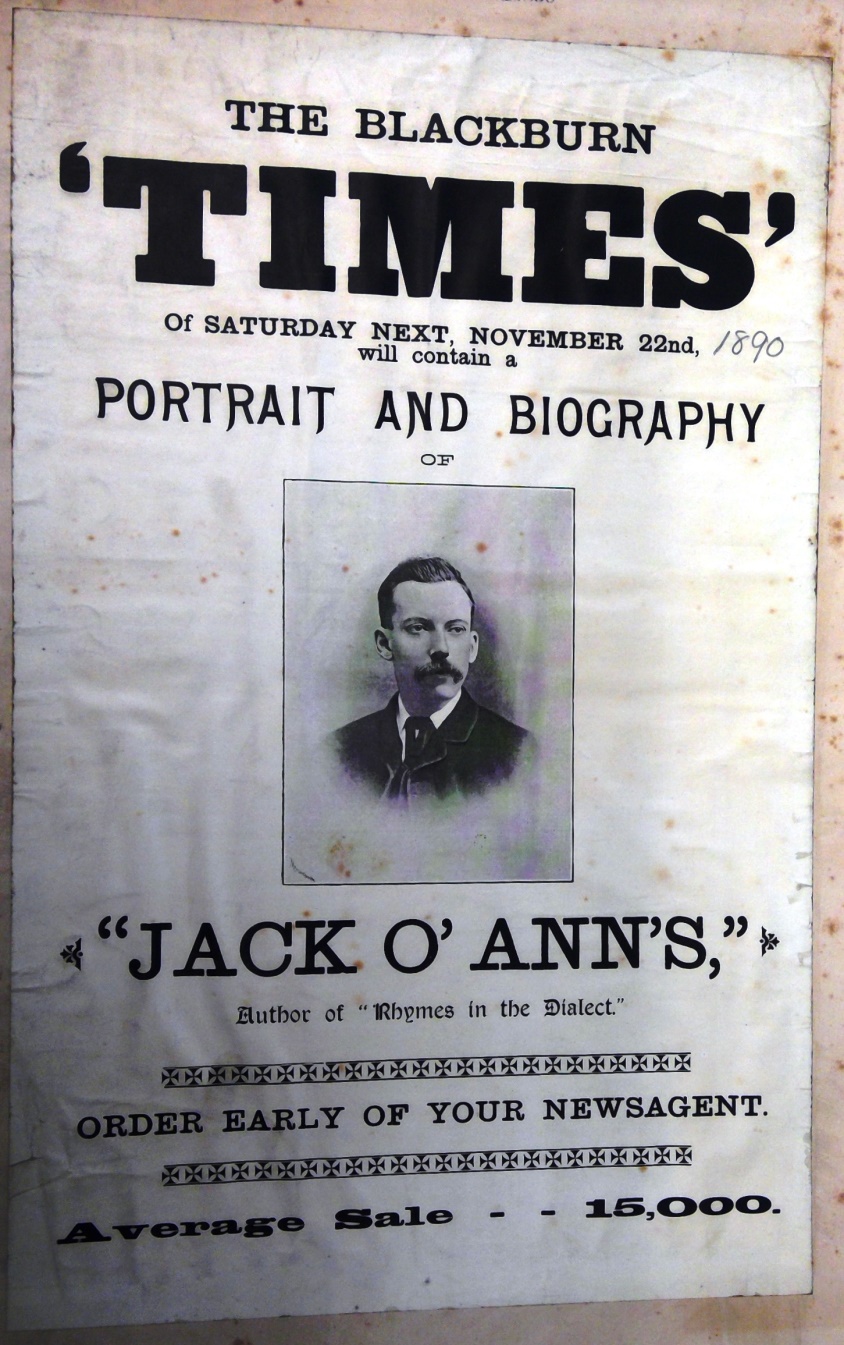

(JACK O'ANN'S)

BLACKBURN'S MOST PROLIFIC POET

Copyright-Blackburn-with-Darwen-terms-and-conditions

John Thomas Baron, Jack o'Ann's

Blackburn, can proudly boast of having had many good poets over the years, some well-known and popular in their time and known even today. George Hull in his book “Poets and Poetry of Blackburn" writes about 56 of them. Names like William Billington, spring immediately to mind, he wrote many poems for various newspapers and two books, “Sheen and Shades" and “Lancashire Songs with other Poems and Sketches". He also kept a beer house on Bradshaw-street known as The Poets Corner, from where for many years he ran a literary club. Another well-known poet of that time was Joseph Baron (no relation to our subject) who wrote both a Blegburn Dickshonary and a Lankisher Dickshonary" These, and most of the others written about by Hull at one time or another wrote poems in the Lancashire dialect. But certainly the most prolific of our local dialect poets has to be our present subject; John Thomas Baron who, for over 30 years, with just one short break due to illness wrote a dialect poem each week for the Blackburn Times and never missed an issue.

John Thomas Baron was the son of John Baron, a card room grinder, and Ann Bond weaver; they were married on the 22nd of February1846. John Thomas was the fourth of six children, two of whom died young. He was born on the 1st of March 1856 at 42 Chapel-street Blackburn. The surviving children were an elder brother, James and a younger brother William, who was born 19th April 1865. Like his brother, William became a poet and wrote under the name of “Bill o'Jacks." There was also a sister, whose name I cannot find, she married a man called Ashover and for some time was the caretaker of the Ragged School, on Bent-street.

In 1859 John's father became ill and so the family moved to the cleaner and healthier air of Blackpool. They resided at “Napier House," 28 Chapel-street. Here for a fee of a penny-a-week John Thomas got his only education, a place was found for him in the infants department of the National School in Bank Hey-street, (just behind where the tower now stands.) His teacher was a Miss Jones who he described as: “An admirable and painstaking lady. Her teaching was excellent." In 1865, when John had turned nine his education came to an abrupt end when his brother William was born, his parents thought he would be more useful at home helping his mother.

Copyright-Blackburn-with-Darwen-terms-and-conditions

42 Chapel-street where John Thomas Baron was born

About a year after the birth of his brother William the family moved back to Blackburn for a short while. Back in his hometown John Thomas got his first job as an errand boy at Anthony Welding's saddlers shop, at 12 Darwen-street, but it did not last long. After just six months back in Blackburn the family returned to Blackpool. John Thomas soon found employment at a newly opened “Dick's Shoe Establishment" in Lytham-street where he remained for the next two years.

On May 23rd 1869 at thirteen years old John Thomas was to suffer the greatest loss of his short life, it was the sudden death of his mother, who he adored. One of the first poems he wrote was dedicated to her; he called it “A Mothers Love." The first verse runs:

There is a flame, more pure and holy

Than that which burns at Beauty's shrine;

'Tis shared alike by great and lowly,

And once—ah, once!—'twas mine.

It lingers sweet in recollection,

And haunts us wheresoe'er we rove—

The gleaming pole-star of affection;

It is—a mother's love.

In 1919, on the fiftieth anniversary of her death he wrote another poem, called simply:

“IN MEMORIAM (Ann Baron died May 23rd 1869.)

The golden glory of a summer's day

Streams from the azure dome wide-arched on high

As blossoms tell the presence of sweet May,

Yet sadly I behold them with a sigh.

On such a day—remembered with a tear—

Grief's first great shadow o'er my life was thrown

Death struck (we recked not he was lurking near,)

The gentlest Teacher Youth had ever known.

Grieving at the loss of his wife John Baron decided to move and on Whit-Monday, 1870 the family came back to Blackburn. Within a few days of their return John Thomas got an apprenticeship as a fitter and turner at Dickinson's Phoenix Foundry Bank Top, the firm made looms and other textile machinery. He would remain there for the next fifteen years.

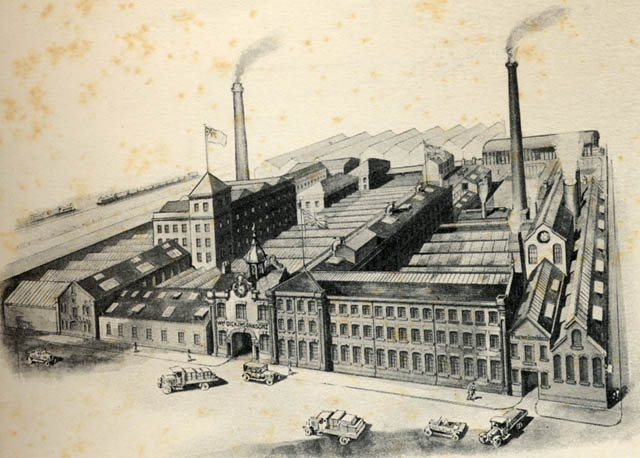

Copyright-Blackburn-with-Darwen-terms-and-conditions

Phoenix Iron Foundry: John served his apprenticeship here as a fitter and turner

While still an apprentice he began to write poetry seriously and had some of them printed in various magazines including “Oldbury Lyrist," “Young Folks," “Rambler," “Echoes from the Lyre," and “Dick Snowdrop's Journal." His brother William latter recalled a tale about this journal, he said: “My brother had hardly passed out of his teens, but even at that early age he had written some fifty or sixty [poems] for the Journal, and was easily, with the exception of “Dick Snowdrop" himself, its most prolific contributor. One morning he received a letter from “Dick" inviting him for supper at the editor's domicile, as slight acknowledgement of his services, and needless to say, this bit of recognition on the part of his editor excited my brother considerably. On the appointed evening he set forth in high spirits, with visions of an epicurean banquet floating before his eyes. But alas, he was quickly to be disillusioned, for the feast he had so eagerly looked forward to eventually materialized into a plate of potato pie, and nothing more."

In an article for Blackburn Times in 1978, J.S. Miller wrote about John Thomas, he said: “He widened his experience by joining the local Artillery Volunteers, being promoted Sergeant when he was only 19—the youngest in the Corps. While engaged in manoeuvres at Southport, he gashed his thumb on a jagged part of the gun mechanism, and reported to the duty surgeon in order to have his wound attended. When the officer asked what on earth he had been doing, the poet promptly retorted, 'Shedding my blood for my country, Sir.'" He was to remain in the Volunteers for seven years.

The first poem he had printed in a newspaper appeared in the Blackburn Times of October 14th 1876, when he was twenty. The poem was called “Hope" and is written in plain verse. He also began to contribute poems to many other newspapers, including the “Blackburn Standard," “Preston Chronicle," “Blackpool Gazette," “The Oldham Chronicle," “The Accrington Times," and “The Blackburn Weekly Telegraph." His second poem in the Blackburn Times was printed on November 17th 1877 and was called “Art and Song" which Edwin Waugh, perhaps the greatest Lancashire poet of the time, had a great deal of admiration for and said that he hoped the author would long be spared to produce poetic work of such quality. John had no poems printed in the Blackburn Times in 1878; however, one appeared in the Preston Chronicle of August 1879 called “Song of the War King." All these were written in plain verse, he had not yet got into the dialect, at least not into getting it printed.

On Thursday May 1st 1879 at 5.30 in the morning, Montague-street Congregational Church held a “May Morning Breakfast" which attracted over 400 diners at a shilling a head. After the meal a public meeting was held when another 400 people came to watch the proceedings. They were entertained with music, recitations and speeches. Prizes were offered for the best two poems on the subject of “May Time," John won the first prize which was Tennyson's complete works in eleven volumes, he was twenty three years old at the time.

As a poet John used many nom-de-plumes “Trouncer," “Borona," “Jounty Baronious," “John Brannot," “Bob o' Clinkems," “Jacobite," “Tummy Tulip," “Byronic-B," “J.T.B." “John T. Baron," “Jo Hotbrann," “Baron." Another name he used was “Nora B," There were not many local female poets at this time and it was thought that “Nora B" was one of them. Perhaps he wanted to write some sentimental poems, which he felt he could not do using the name of a man. Eventually it was realised that “Nora B" was simply Baron backwards! His most famous non-de-plume by far was “Jack o' Ann's—this way of writing a name continued an old Lancashire custom, it means Jack of Ann's or Jack son of Ann—which he wrote most of his dialect work under. George Hull tells an amusing story in his book “The Poets and Poetry of Blackburn" (written in 1902) he says: “For a long time after Mr. Baron adopted the nom-de-plume of “Jack o'Ann's," he kept his identity secret… While on his way to work, Mr, Baron met, in Salford an old shop mate who had often read and admired the poems, signed “John T. Baron" or “J.T.B."… This admirer asked his poet friend if he could tell him “who that `Jack o' Ann's` was?" Our poet answered evasively, that he was not at liberty to divulge printing-office secrets; and this answer proved affective. When, however they had parted at the bottom of Eanam brow the inquirer suddenly stopped and called out to the poet, some forty yards away—

“Heigh Jack."

“Well; what's up?"

“Tha's written some fairish bits i' th' pappers neaw an' ageon; but tha'rt a foo compared to yon `Jack o' Ann's.`"

In May 1877 John married Sarah Watson with whom he had seven children, four boys and three girls, sadly two of the boys died in infancy. He wrote a poem to the memory of one of his dead sons (see below.) In 1885 he left Dickinson's foundry and moved to Henry Livesey's Greenbank works, where he was to remain for the rest of his working life. About a year after this change, on October 30th 1886 he had his first dialect poem printed in the Blackburn Times under his pen name “Jack o' Ann's." He had expected to see it in the usual poet's corner of the newspaper, but to his surprise the Times printed it in a place of its own and called it “Rhymes in the Dialect." The poem was called “A Comfortable Smook." The following week—November 6th 1886—a short poem called “Audley" by a poet with the initials “W.P" appeared in the “Rhymes in the Dialect" column, with “Jack o' Ann's dialect poem “To the River Blakewater" appearing in the usual poets corner.

The next dialect poem John had printed in “Rhymes in the Dialect" was a very touching poem called “Johnny's Clogs." This poem was about the loss of one of his children. I have copied it in full:

JOHNNY'S CLOGS

Howd on, theer! Dunnot use 'em rough but put 'em gently deawn;

They're nobbut hawf-worn clogs to yo, wi' tops o' musty breawn;

To me, they're sacred links 'at bind my thowts to one i' th' mowd;

Eawr Johnny wore those clogs afooar Deeath med him stiff an' cowed;

They're but a pair o' little clogs, wi' irons rusty red,

Yet thowts they wakken i' my heart, ov a life-star 'at's fled.

For th' gloom o' grief seems darker neaw, an' Life's nowt near as sweet

As when he used to welcome me wi' hooam smiles every neet.

Tho' th' sod's bin o'er him money a while, to life he's gi'en a grace;

Oft reawnd my cot aw wond'ring stare—there's summat eawt o' place.

Thad lad wur th' best mate 'at aw hed i' sunshine or i' storm.

Wur aw a King, my creawn aw'd give, to clip th' familiar form.

No other eye could shine like his; his speech, so soft an' mild,

Fell o' my ears like music-strains,—he wur my darling child.

No hand seemed hawf so nice to grip, nor greetin' e'er so kind

As his; an' neaw aw seem to hear his voice I' every wind.

Last neet, aw see a little star, 'at fairly pleased my eye,

It seemed o ov a flutter theer, heigh up i' th' dusky sky.

An' then a thowt flashed thro' my mind 'at med my eyeseet dim.

He wur My child! Aw stood on th' earth an' looked tort Heaven' on him.

Con he be waitin' for me theer, hawf-way fro' th' gowden Throne?

Wur them his wings 'at fluttered breet heigh i' thoose realms unknown?

His bonny face seems allus near, an' th' love for him shall be

Held sacred i' this heart o' mine reight to Eternity.

For the next thirty-three years he was the sole contributor to “Rhymes in the Dialect" and not once did he miss handing in a dialect poem for the column. George Hull says that after his first poem was printed in “Rhymes" he never wrote anything for another newspaper.

It should be remembered that while he wrote his weekly contribution to the Times he was working full time at Livesey's Greenbank Foundry, he was also was an official for the Amalgamated Society of Engineers. To their credit Henry Livesey's gave him time off to fulfil his writing obligation to the Blackburn Times when he become well known as a poet.

In 1889 on Edwin Waugh's 71st birthday, John wrote a poem which he dedicated to the writer, it was called “To Edwin Waugh (on his 71st birthday") which had the prefix “Tha good owd King o' Trumps—God bless thi silver yure!" At this time Waugh was living in Brighton and so John sent him a copy of the poem together with a letter. Waugh wrote back: “It's a cheering thing at my time of life to feel that I have the friendship and good wishes of so many of the people of my native county."

According to George Hull John Thomas wrote “for amusement rather than the instruction of the reader", he seemed to enjoyed writing poems describing events, such as New Years, Valentine's day, Pancake Tuesday, Easter, and Christmas, although these were annual events the poems he wrote about them when their times came around were never the same. He also wrote about the annual holidays, about going on and coming back from.

By 1906 John had been writing for “Rhymes in the Dialect," for 20 years and on the 13th of January of that year, he had his one thousandth poem printed in that column, The poem was called “'Lectioneerin" it told of the troubles a man went through on the days leading up to an election, how he was pesterd by his friends, neighbours and politicians trying to win him over to their way of thinking. In the same Issue George Hull wrote a poem and called it “A Tribute To Jack o'Ann's"

An article printed in the Blackburn Times for the occasion said: “it would be absurd to claim that every single rhyme…would satisfy a highly critical taste, but when we recall the fact that the “Rhymes" which are from half to three-quarters of a column long, have never once failed to appear at the appointed time…we are filled with amazement." The article goes on to tell how John had over the years been in correspondence with such well-known authors and poets as Harrison Ainsworth, Samuel Carter Hall, Ruskin, and R.D. Blackmore who all applauded his dialect and plain verse poetry. It also quotes John as saying: “I have endeavoured at all times to give my readers something fresh and tried to show the people just as they are or were. My great aim has been to be a help and consolation to my fellow workers. My greatest difficulty is to find a suitable subject that found, the rest is fairly easy."

John carried on writing poems for the Blackburn Times until June 1919 when, at 63 years old, he suffered a serious illness, which confined him to his bed. The illness prevented him contributing his poetry the Blackburn Times and the Editor reprinted some of his older work beginning with “A Comfortable Smook." William, his brother, said that during this illness when he found he was unable to contribute to the Blackburn Times, he cried like a baby. By October however John was on the mend and on the 16th of that month he resumed his “Rhymes in the Dialect" with a poem called “A Day at Blackpool." Once again John was writing a poem a week for his “Rhymes in the Dialect" and he continued for a further two years until 1921. On the 7th of June 1921 his brother William received a letter at his home in Rochdale from John. William said: “The feeble and uneven scrawl off the envelope—so unlike his usual flowing hand-writing—filled me with fears and misgivings, and these were only too speedily realised as I opened the letter and hastily scanned its contents." It told William that his brother was seriously ill and he wanted him to go immediately to his home. When William arrived there he was shocked at the great change in his brother. The once strong and healthy man had wasted to a shadow. He was however still cheerful and they talked of the old days, of authors and poets. Old friends of the poet were constantly visiting the house. One fellow poet who visited the house was John “Jack" Rawcliffe who was about to sail the following day for a new life in America. During their conversation the name of William Billington came up and some comment was made about the poets work. At that Jack Rawcliffe jumped up and said: “Neaw aw'm nooan avin' a word ageon Billington's poetry, becose moast on it's gradley good stuff, but no poet should write on subjects as he knows nowt abeawt, an' that's what he's done. For instance, just tek his poem, “Look under t' leeoves iv yo want ony nuts." Why its ridiculous, to say t' leeast on't. Nuts ripen i' t' sun, as every foo' knows, and yo'll hev to look aboon t' leeaves for em not under, iv yo want to find ony. But ther's one thing certain, if Billington hed bin forced to gooa gatherin' nuts to fill place o' butter cakes, like eawr Dick an' me hed to do mony a time as lads, he'd hev known better than to mek sich a silly blunder."

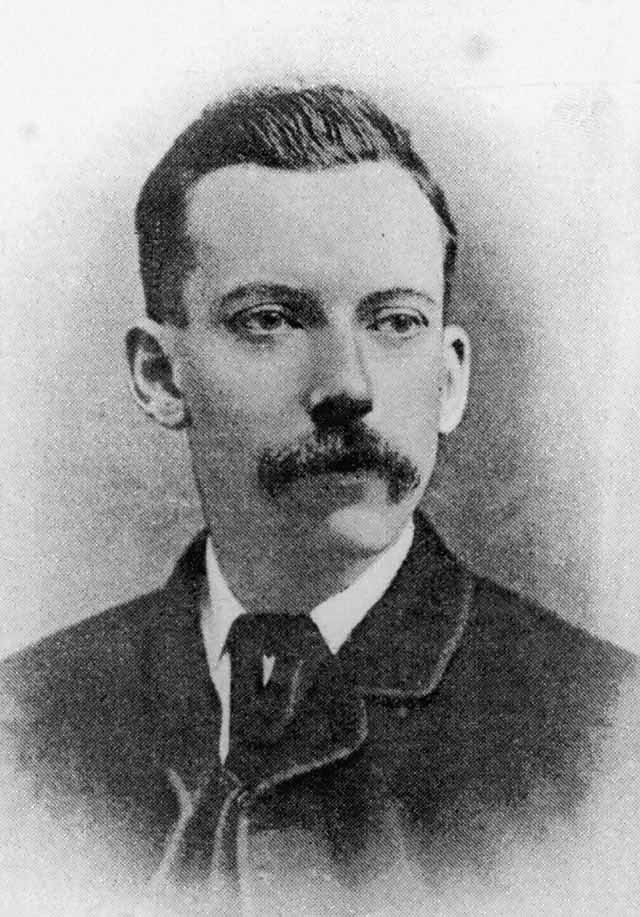

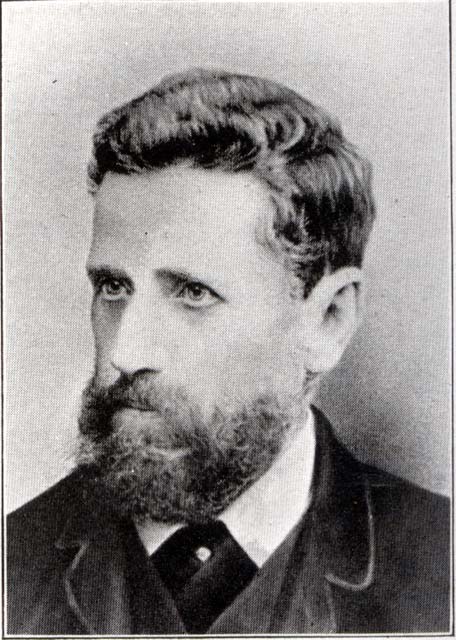

Copyright-Blackburn-with-Darwen-terms-and-conditions

John Rawcliffe poet and friend of John Thomas Baron

With much difficulty John continued writing Rhymes in the Dialect until December 31st 1921 when he contributed his last poem called “A December Nights' Dream." His health was rapidly deteriorating, and on February 3rd 1922 he died at his home at 92 Scotland Road aged 65. The funeral took place on Wednesday 8th of February when he was interred in the Blackburn cemetery, Whalley New-road. As well as family many of his old friends also attended the funeral including George Hull, the author, James Rostron, Editor of the Blackburn Times, and Mr and Mrs. Robinson who represented the Lancashire Authors' Association.

On March 17th 1924 the Mayor and Mayoress welcomed the Lancashire Authors Association to Blackburn when they held a commemorative meeting for John at the lecture hall. They talked of the contributions John had made to dialect poetry and also discussed the direction dialect poetry was going. Someone suggested that it would be a grand memorial to Jack o' Ann's if a selection of his work could be made into a book, but this was never done. After the meeting they moved onto the library where, in the art gallery an enlarged photograph of John Thomas Baron framed in oak was unveiled by William Baron and presented to the Corporation. The frame had the inscription “John Thomas Baron, “Jack o' Ann's," author of Rhymes in the Dialect. Born March 1st 1856, died February 3rd 1922. Presented by the Lancashire Authors' Association, March 1923."

After this they went to the cemetery where the chairman of the L.A.A. laid a laurel wreath at the poet's grave. The day finished with tea and a public meeting back at the lecture hall, where James Baron, one of John's sons, read a poem written by his father.

In his day John Thomas Baron was a very popular and prolific local poet. In 35 years he wrote about 1,800 dialect poems for the Blackburn Times. It is thought that he must have wrote at least 3000 poems altogether.

Expatriates from all over the world who had their origins in East Lancashire and had the Blackburn Times delivered through the post would contact the paper saying how the poems of Jack o' Anns brought a little bit of Lancashire to their adopted part of the world.

It is unfortunate and surprising that a compilation of his poetry was not put together until 1978. At that time his great-grandson, John Baron of Accrington made an anthology of almost 150 poems by John Thomas Baron and called it appropriately “A Cotton Town Chronicle." In it are verse in both dialect and plain verse and is well worth reading if you can borrow a copy.

Copyright-Blackburn-with-Darwen-terms-and-conditions

The grave of John Thomas Baron at Blackburn's Whalley New Road Cemetery

I will finish by giving you the very first poem “Jack o' Anns" wrote for the column Rhymes in the Dialect.

“A Comfortable Smook."

Aw,m bothered nooan wi' acres broad, nor burdened mitch wi' wealth;

For tried friends aw've a ready hand, an'for misel' good health!

When work is o'er, at hooam aw sit i' th' cosy cheer i' th' nook,

An' reych my pipe deawn to enjoy a comfortable smook.

There's doctors, nobs, an' simple fooak, wi' faces long an' pale,

'At's fairly shocked at pun or jooak or gradley merry tale.

They say as 'bacco's pisenous, an' dolefully they look

On every hearty cock who loves a comfortable smook.

It's nowt to me, they suit thersels, they've narrow hearts an' brains;

They suit thersel's—but nobr'y else,—an' ged chaffed for their pains.

Mi grondad wur a veteran bowd, who fowt wi' th' “Iron Duke."

He oft enjoyed—an' sooa will aw!—a comfortable smook.

When sorrows linger reawnd my mind, an' try to poo me deawn,

Aw leet my pipe—a puff o' wind, an' troubles leave my creawn.

They ged i' th' draft wi' t' smook; up flue they fly, an' quit my nook.

There's nowt 'at kills care sooner than a comfortable smook.

It's th' true philosophy o' life to tek things as they come;

An' if yo have a gradely wife an' childer reet at home,

Yo' needn't cry o'er th' Past, nor try to peer i' th' Future's book;

Use th' Present weel, an' calmly tek a comfortable smook.

I' winter time, when neets are dark, an' blustry winds blow cowd,

My pipe, lit wi' contentment's spark, brings hooamly joys untowd.

When summer fleawrs i' th' sunleet gleeam aw ramble deawn bi th' brook,

An' birds sing for me while aw hev a comfortable smook.

Aw've oft watched th' smook arise an' curl i' queer shapes o'er my head,

But queerer thowts hev filled my brain wi' th' fancies 'at they've bred.

Like 'bacco, Life soon burns away, eawr ashes gooa to th' rook;

So while Life lasts, live reight, an' tek a comfortable smook!

by Stephen Smith

back to top

Andrew Hobbs, University of Central Lancashire

Blackburn Local History Society, 27 Oct 2015

Introduction

Any cultural map of Victorian Blackburn would have included Mount Parnassus, the mythical home of the muses. As a book reviewer wrote in the Blackburn Standard in 1888:

‘Notwithstanding our unsavoury reputation; and notwithstanding the smoke in which we are enveloped, Blackburn is a town, which, in a literary sense, has no need to be ashamed … On its hill sides and by its streams poets wake their lyres …’ (1)

George Hull’s excellent anthology The Poets and Poetry of Blackburn (1902), includes more than 50 local poets, and presents Blackburn’s poets as a major part of the town’s history and poetry as Blackburn’s pre-eminent art-form. The town was exceptional, in the quantity and quality of poetry it produced. We can get a flavour of this thriving working-class literary culture from brief biographies of some of its leading figures (with most of the information taken from Hull’s book).

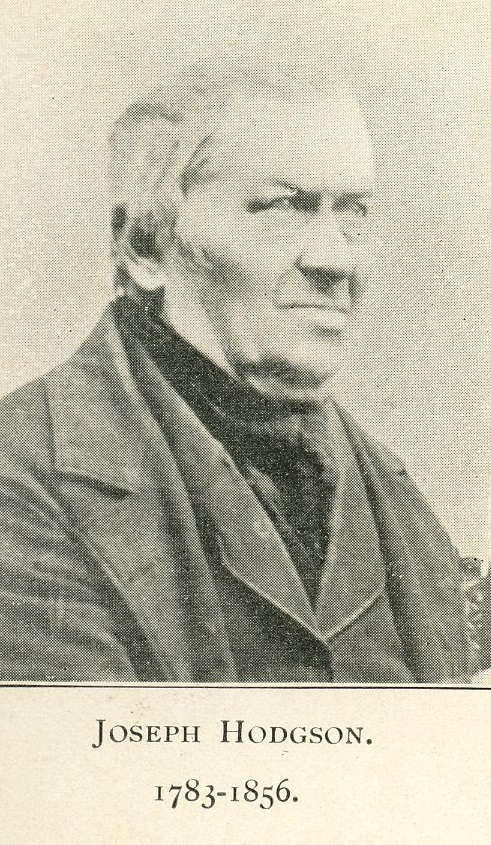

Joseph Hodgson

One of Blackburn’s earliest poets was handloom weaver Joseph Hodgson (1783-1856), whose verse was published in the Blackburn Mail and the Blackburn Standard. When he died, he left a library of 800 volumes which filled 2 wagon loads when removed from his house.

Richard Dugdale

Richard Dugdale (1790-1875), a former soldier turned engraver, and self-proclaimed ‘Bard of Ribblesdale’ (many Blackburn poets took or were given these honorifics) claimed to have met a relative of Scottish poet Robert Burns, of whom he was a great admirer. Burns’s class, his rootedness and his proud use of his own language, gave legitimacy to writers of working-class dialect poetry in Lancashire and across Britain (2).

John Critchley Prince

John Critchley Prince from Wigan was a member of the Manchester ‘Sun Inn’ group of writers (who met in the pub of that name next to the cathedral), lived in Blackburn for some years, and associated with the town’s poets.

John Baron

John Baron (1823-80), another cotton operative, known as the ‘Grimshaw Park Poet’, besides his many newspaper poems, he had one volume published, jointly with compositor James Walkden, nephew of the publisher of the Blackburn Standard (3).

William Abram

William Abram (1835-94), trained as a printer, he wrote poetry in his youth and became the first head of Blackburn’s newly opened ‘free’ or public library in 1860. In 1867 he joined the Blackburn Times as editor, and helped to establish it as the town’s leading paper. Abram, was a keen promoter of local literary talent; 'he loved Literature and taught others to love it'. He liked to read aloud the poetry of Tennyson, Wordsworth, Byron and Swinburne and the Elizabethan and Cavalier poets, and co-edited the complete works of the Cavalier poet Robert Herrick (with Rev. Alexander B Grosart, minister of St George’s Presbyterian Church of England, Blackburn). He was a founder of the Blackburn Literary Club and ‘donned wig and gown, as Counsel in the famous (mock) trial, "Bardell versus Pickwick"’(4). – re-enacting a scene from Dickens’s Pickwick Papers.

Weaver Henry Yates (b. 1841), named the ‘Bard of Islington’ by his neighbours in that district of the town, used ‘Tansy Tuft’ as a pen-name for his dialect poetry. He was a prolific writer of prose and verse for Blackburn and Preston papers and for Ben Brierley's Journal, Cassell's Saturday Journal and others. Some of his lyrics were set to music by a local organist and composer, and he had one volume of poetry published 1904 by Blackburn and District Authors’ Society.

John T. Baron

Foundry worker John T Baron (1856-1921, no relation), had many poems published in the local Dick Snowdrop’s Comic Journal and went on to write some 1,800 dialect poems for the Blackburn Times under his dialect nom de plume, Jack o’Ann’s.

William Billington

The most popular Blackburn poet was mill worker William Billington (1825-84), whose verse appeared in the Blackburn Standard, Blackburn Times and other local papers. He was depicted as 'William Bentley' in William Westall's novel Red Ryvington, and published two volumes of poetry, with Abram offering editorial help for the first.(5) He was born in Samlesbury, worked in a Blackburn mill as a child but hated it, and took on a pub, the Nag’s Head, Northgate. He was a founder member of the Blackburn Mechanic's Institution, taught grammar in a school in exchange for lessons in mathematics, advised trade unions, lectured on and debated religion and politics at any opportunity, and formed a Mutual Improvement Society, which met in a hayloft.

He is remembered mainly for his dialect ballads about the impact on workers of the "Cotton Famine" of 1861-64. His most famous poem Th' Shurat-weyvur's song was published as a broadsheet (a single sheet, sold for a penny) at the height of the Famine , selling 14,000 copies .

There was a huge response from the public and from other poets to the death of Billington. A public appeal for funds towards a memorial was launched. Contributors included Blackburn Literary Club (£7, 3s), many local litterateurs, publishers of the two Blackburn weeklies (10/6 each) and the Friendly Discussion Club at the Dog and Otter Arms, Great Harwood (8/1), among many others. The money paid for an ornate gravestone and a portrait which hung in the hall of the Free Library.(6)

There were many more Blackburn poets – more than 50 are mentioned in Hull’s book alone. Abram, in his posthumously published Blackburn Characters of a Past Generation, wrote that Blackburn was ‘haunted by quite a small flock of minor poets, or person who imagined themselves to be poetically inspired’.

Billington and Abram were born leaders, and were committed to education and culture for all. They knew that working-class writers could produce poetry just as good as that written by more privileged poets, and they worked hard to develop and promote the work of Blackburn’s bards.

Bardic communities

Brian Maidment has written about the working-class adoption of the Romantic idea of the bard encouraged the idea that ‘all individuals possessed the sensibility, if not the skill or linguistic resources, to be poets.' Some of the poetry published – and unpublished -- in the local press suggests that many people believed lack of skill was no barrier, that everyone had the right to express themselves in verse, to indulge in what Laporte calls ‘poetic behaviour’ (7). Maidment sees the self-educated poet as a ‘slightly more articulate neighbour’(8).

Romantic poets, especially Wordsworth and Shelley, had raised the status of the bardic identity -- associated with 'unlettered' poetry, 'spontaneous talent' -- making it very attractive to provincial self-educated writers who were excluded geographically and culturally from the centres of literary power.

Maidment lists some features of a Bardic community, and Blackburn fits the bill.

1. Dedicatory poems

Blackburn’s poets were always writing poems about each other. When John Baron’s former teacher Charles Tiplady was 60 and Baron 50, ‘an exchange of reminiscences in verse took place between the teacher and scholar’, with poems such as Tiplady’s ‘Answer to John Baron’s Retrospective Stanzas’. Billington’s elegiac ‘‘Where are the Blackburn poets gone?’ lists 26 other writers.

2. Public and official recognition of the Bardic role

In the 1850s ‘the Scotchmen of Blackburn gave a banquet to the "Bards of Blackburn”’. George Barton, a Blackburn Standard employee and choirmaster at St James’s church, set local poets’ work to music, including poems by Billington and John Baron (9). John T Baron was given time off work from Livesey’s Greenbank Foundry to write his weekly verse for the Blackburn Times when he became well known as a poet.(10)

3. Public duties – like a local laureate

Poems by local poets were read and recited aloud – by the poets and others – at entertainments – church socials, fund-raising events and significant occasions.

Public recognition

Local writers were part of the same interpretive communities as their readers, who valued the local poetry of the local press. An obituary of Billington claimed that there are those amongst the rank and file of our Blackburn population to whom the homely rhymes of a Billington are more congenial and more dear than the stately and sustained splendours of a Byron, a Tennyson, or a Scott. (11)

Some of the keener readers are revealed in a series of debates about the local press held at a Sunday-night debating club in the Regent Hotel in 1888. Debaters spoke knowledgeably of the three weekly papers published in the town, and of their favourite contributors and editors, and quality of poetry published.

Many readers memorised local newspaper poetry, or quoted it in print and from the platform and the pulpit, challenging received ideas about the ephemerality of newspapers. John Walker, a Blackburn-born journalist, was able to quote a verse from a Billington poem written 25 years before.(12) Dialect poetry in particular was read and recited at local events and entertainments.(13) The fact that these readers treasured and used such poetry, in ways we tend to reserve for only the ‘best’ poetry, challenges our judgments of poetic quality and the limitations of ‘bad art’.

Bards had meeting places

Blackburn had many clubs, societies and pubs where those interested in poetry and other literature could meet. There was the Blackburn Literary Club, on Fleming Square, with its lectures and annual dinners. Members occasionally read and critiqued their own poetry. There were debates and lectures in pubs -- Mr Gregory Walker, landlord of the Spread Eagle Hotel hosted ‘conversaziones’ (discussions) every Sunday evening. He had a large room was fitted up and specially adapted for these events, and other pubs followed his example. ‘Poet Billington was engaged to inaugurate the new institution, and he performed the duty with much eclat, and he continued as lecturer and leader of debates until his second marriage.'

There was the Bohemian Club – ‘a kind of Mutual Admiration Socirty for our amateur writers and others who have some connection with journalism, and more ambition that way than they have been able to gratify.’(14) They met every Thursay in the Regent Hotel, Penny St, then took over a room previously used by the YMCA, at the corner of Ainsworth St and Water St.

The Black Horse on Northgate was 'the rendezvous of lawyers, auctioneers, agents, reporters, local poets, and literatteurs', run by Will Durham, known as ‘the Blackburn chronologist’. Journalist and poet William Whitaker recalled a visit with another reporter in the 1850s or 1860s, where they found John Boothman of the Blackburn Weekly Times and 'on the other side sat the burly bard of Ribblesdale, Dugdale, and two other poets -- Billington and Baron, and snoring in the chimney corner sat John C Prince ...'

Billington himself became a pub landlord across the same street, at the Nag’s Head, although 'the descent from Parnassus to the beer-cellar ... from Helicon to Dutton's brewery ...' seemed wrong to some of his friends.(15)

Abram describes one night when about 20 members of the Literary Club went for a drink at Billington’s pub. ‘Among the party were poets, chief of them the host himself; excellent elocutionists, singers, journalists, and literary critics… Recitation, criticism, song, discussion, comical story, and bandied “chaff,” succeeded each other’ until a passing policeman reported them all for drinking after hours; the chief constable quietly let the matter drop. (16)

Billington then moved to a Dutton's beerhouse on Nab Lane, which he called Poet's Corner, and ran from 1875 until his death in 1884. His dialect songs hung for sale in the window, 'printed on single sheets for sale at a penny each', and inside, according to a description by Whitaker:

'There is nobody in the front room to the right, so we turn into one to the left. This apartment is appointed to various capacities of most heterogeneous character. It is at once the kitchen, tap-room, study, and gymnasium, and the table, of about four feet square, answers the threefold purpose of dining-table, ale-bench, and writing-desk. The poet is sat in an arm-chair, occupying a convenient position on the ingle side of it. That portion of the table is consecrated to the muse, and when we enter we find it littered with scraps of manuscript. He is not cultivating poesy just now, but peeling potatoes ...'

Billington ran free grammar, composition and elocution classes on Wednesday evenings at his beerhouse; aspiring poets used to take their poems to him there, for his criticism and suggestions. These humble premises became an important centre of working-class literary and educational activity, with Sunday evening debates e.g. ‘Wordsworth v. Byron’, lectures and poetry readings.(17)

Poetic rows

Blackburn’s poetic communities were not always harmonious. Poets could be vicious and mean, writing satirical and even obscene verses about each other. In one argument through the letters column of the Blackburn Standard in 1880, John T Baron and Billington accuse each other of plagiarism; Billington put his attacks into sonnets, concluding with one which ends: ‘he’s but a shrub on which some muse hath spit/By name a Baron and by nature barren.’

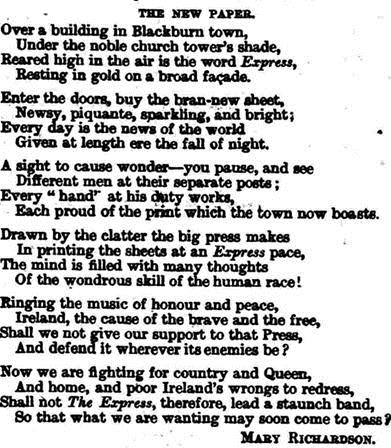

When Abram resigned from the Blackburn Times in 1887 over Gladstone’s Irish Home Rule policy, he jumped ship to a new Conservative paper, the Blackburn Express. The outrage among the town’s Liberals at this change of allegiance was expressed in typical poetic form. Abram published a poem from the unknown Mary Richardson, welcoming the town’s new paper. He did not notice that the poem was an acrostic, the first letter of each line spelling out its message.

The New Paper (18)

The new paper carried little poetry after that.

Local papers at the heart of this poetic community

Local newspapers traded on the sense of place and local patriotism of their readers, and poetry’s emotional power and cultural capital could be harnessed to their project of giving significance to ordinary provincial places, far from the salons of literary London or the heady heights of Mount Parnassus.

You could have local poetic cultures without the local press – but it helped, hugely. Newspapers fostered a sense of poetic community, connected readers to writers -- gave them an outlet and a loyal following – and publication in the local press, alongside public performance, was the main outlet for these poets.

Some poets collected their verse in book form – but many people too poor to buy poetry books – making newspapers more important. The papers boosted the status of poets through encouragement and reviewing, of publications and submitted amateur poetry – they took them seriously. Individual journalists with literary interests were important, e.g. Abram, John Walker. Newspapers preserved the memory of poets when they died, with obituaries, elegies, anniversaries, and biographies. And (to divert for a money) they occasionally offered financial support.

Payment

The Blackburn Standard paid Billington when he was down on his luck for a 6-month series of "Samlesbury Tales and Legends" about his birthplace. John Critchley Prince appears to have been paid a regular sum by the Preston Guardian from 1853, whilst living in Blackburn, judging by the quantity of his poetry published there. The arrangement probably began after he wrote to the editor:

I shall be happy to contribute now and then to your paper; and if you could afford to pay me two or three shillings a week, I will engage to supply you with lyrics (weekly), on moral, elevating, and cheerful subjects. They shall be written expressly for your journal… Can you set me a literary task? I will do the best I can.

There was paid work for local poets at election times, writing political squibs in support of one or other party, or sometimes both. Abram engineered the exposure of one pen for hire, John Baron, during the 1868 election:

Like the rest of the Blackburn “School” of Poets, almost without exception, “Jack” Baron, when party politics were rife, yoked his Pegasus to that car, and wrote election rhymes – squibs, satires, and panegyrics – charged with violent expletives …(19)

Baron was a Tory, writing two or three pieces for the Standard and the Patriot each week, while most poets were Liberal supporters, being paid by the candidates to write verses for the Liberal Times. Baron thought the Liberals paid more than the Tories, submitted an anti-Tory rhyme to the Times with accompanying pseudonym, but Abram ‘accidentally’ printed his real name beneath the poem. Baron was furious.

Why was Blackburn so poetical?

"Blackburn … has produced more weavers of calico and of verse than any other town in the United Kingdom,” wrote the poet and journalist John Walker, in the introduction to a volume of poems by the Rawcliffe brothers. Blackburn had an unusually vibrant working-class poetic culture – but why?

Blackburn’s working-class literary culture was part of a broader local self-improvement network, including the Mechanics’ Institute, discussion classes and debating societies.

Or was it the newspapers, who were more welcoming to working-class poets, unlike papers in some other towns? And then it became a self-perpetuating tradition in Blackburn? Editors such as Abram encouraged readers to become writers, as with George Thomas Collins:

‘I began life as a brush maker, and am still following that occupation … although I had written, in my childhood and youth, some rhymes that I did not consider fit for print, I don’t suppose I should have ventured to publish any had my esteemed friend, Mr. J. T. Baron, not persuaded me to send one piece to the “Blackburn Times” for publication … I consider it a praiseworthy feature of Blackburn journalism that it encourages and fosters local talent, especially among the workers in this very busy hive of industry…’ (20)

Whatever the reasons, Blackburn’s poets elevated the everyday and made it special. One of Billington’s obituaries captured the sense of literary magic and prestige that poetry could impart to ordinary places:

he had felt the fresh breeze of Parnassus, the Muses had anointed his eyes until the grimy streets of Blackburn, the moorlands that hedge us in, and the people that move to and fro among our thoroughfares and mills became the themes of rhapsody and verse.(21)

Bibliography

1. ‘Literary Blackburn and a Letter from Edwin Waugh’, Blackburn Standard 28 April, 1888.

2. William Abram, Blackburn Characters of a Past Generation (Blackburn: Toulmin, 1904), 40-41.

3. John Baron and James Walkden, Flowers of Many Hues (Blackburn 1847).

4. Prefatory dedication by Abram's son, Edmund, in William Alexander Abram, Blackburn Characters of a Past Generation (Blackburn: Toulmin, 1894).

5. George Hull, ‘William Billington: A Centenary Memoir’, Northern Daily Telegraph, 4 April 1925; Abram, Blackburn Characters of a Past Generation., 224.

6. Blackburn Standard 25 September 1886, 1; Hull 231.

7. Brian E Maidment, ‘Class and Cultural Production in the Industrial City: Poetry in Victorian Manchester’, in City, Class and Culture: Studies of Cultural Production and Social Policy in Victorian Manchester, ed. Alan J. Kidd and Kenneth Roberts (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1985), 153.

8. Maidment, 159.

9. ‘Anecdotes concerning the Blackburn poet Richard Dugdale, related by William Billington’, cited in John Critchley Prince’, http://gerald-massey.org.uk/prince/; Abram, ???

10. Smith, ‘John Thomas Baron’.

11. Blackburn Standard 12 January 1884, p2.

12. ‘Aker Whitt’ [William Whitaker], ‘‘Personal Reminiscences of the Poet Billington: V’, Blackburn Times, 1 October 1887.

13. ‘Literary Blackburn and a Letter from Edwin Waugh’, BS 28 April, 1888.

14. Jesse McQuail], ‘Blackburn as a Literary Centre’, Blackburn Standard & Express, 4 April 1891.

15. Whitaker, ‘Personal Reminiscences: VIII’, Blackburn Times 22 Oct 1887.

16. Abram, Blackburn Characters of a Past Generation, 229-31.

17. Watson, Michael. ‘William Billington: Cotton Operative, Teacher and Poet’. Transactions of the Lancashire and Cheshire Antiquarian Society 134 (1985), 82.

18. Blackburn Express, 27 Sept 1887.

19. Abram, Blackburn Characters of a Past Generation, 334-35.

20. Hull, The Poets and Poetry of Blackburn.

21. Blackburn Standard, 12 January 1884, 2

back to top

By James Dunn

There has recently come into my possession (writes Mr. James Dunn, of Montague Street, Blackburn) a most interesting literary manuscript associated with the career of a well-known Lancashire poet of the past, and incidentally connected with the life and labours of a former prominent Blackburn politician and temperance reformer, and which is also identified with the literary history of the town itself. The document in question was purchased by me through the catalogue of a London bookseller, and is the original manuscript of John Critchley Prince’s poem, “The Angel of Temperance,” dedicated by the poet to the late William Gregson, who, at the time the poem was written, occupied the position of temperance missionary in Blackburn.

It will be remembered by those who are acquainted by the life of this ill-starred poet, that although John Critchley Prince was not a native of Blackburn, he paid many visits to this town, and on several occasions during his wandering life both resided and followed his occupation as a journeyman reed-maker here. He appears to have first visited Blackburn in the month of July 1843, being then about thirty-six years of age, but his stay on this occasion was for a few weeks only. At this time, he had already established a reputation as a writer of more than exceptional ability, his first volume of poems, “Hours with the Muses,” having been published in Manchester two years previously, and the work had met with remarkable success. Ten years later, in the early part of 1853, he came to Blackburn again, this time as a resident, for he remained nearly two years following his occupation as a reed-maker, his employer being Mr. David Curruthers, head of a family of well-known reed manufacturers in the town.

He first resided with a Mrs. Blakeley at 34 Bent Street. The adjoining house, no. 36 still exists, but no. 34 was demolished some years ago to make room for the present Ragged Schools. He afterwards removed to the neighbourhood of Fleming Square, and here, faithful to the tradition associated with the lives of other “wooers of the muse poetic,” he lodged in a miserable garret. Lter on he changed his habitation again, this time residing with Mr. Henry Liversege in Anvil Street. During his two years residence in Blackburn Prince was constantly occupied with his pen, writing a number of poems and lyrics, several of which appeared in local and other papers and magazines. Unable, because of his unsettled habits and roving disposition, to remain for long in any particular place, Prince quitted Blackburn towards the close of 1854, to return again the following July, after an absence of only a few months. He found work this time in the manufactory of a Mr. Partington, and a second time took up his residence with Mr. Liversege in Anvil Street. His stay on this occasion, however, was of short duration for once more the wander lust, and the pressure of circumstances, impelled him to leave Blackburn for “fresh woods and pastures new”. It may be cited here as an example of the restlessness which characterized poor Prince throughout his career, that at one period of his life - as the more illustrious but hardly less fortunate poet, Oliver Goldsmith, had done a century before – he tramped on foot through France and parts of Germany in search of employment, his only possession being ten sous in his pocket and an ill-furnished knapsack on his back, subsisting for weeks upon the charity of the few English residents he was fortunate to meet on his way, for he was unable to speak either French or German.

Early in the spring of 1858 Prince was again in Blackburn, and on this occasion, he resided with Mr. John Harwood, a well-known and highly respected master painter and decorator, who became a devoted admirer of the poet, and to whom Prince was deeply attached. In the interval two more little volumes of Prince’s poems had been published, entitled respectfully “Dreams and Realities” and “The Poetic Rosary,” the latter being dedicated to Charles Dickens. It was whilst Prince was staying in Blackburn at this time that the foundation stone of the present infirmary was laid, and in response to an application from the committee who had the matter in hand the poet composed two hymns for the occasion. The ceremony took place on Whit-Monday, May 24th, 1858, amidst general rejoicing, and the hymn selected, which commenced with the line.

Lord, on this bright, auspicious day

was sung by thousands of Sunday-School scholars to the tune called “Warrington.” This hymn afterwards became very popular, and it is said that Prince often shed tears on hearing it sung.

Prince’s circumstances about this time were at a very low ebb. For years his life had alternated between squalid poverty and more or less squalid improvidence. Poet’s, from time immemorial seem to have had meted out to them by fate a more than usual share of the misery and ill-luck of this world, but it is doubted whether the abject literary hack who scribbled for the Griffiths and the Newberrys of the eighteenth century, or the most impecunious denizen of Grub Street or Shoe Lane, in the worst days of their degeneracy ever touched such depths of wretchedness and want as many times as did poor old John Critchley Prince during his chequered life.

As far as can be ascertained, the last visit made by Prince to Blackburn was in the early part of 1860 and judging from the heading from a letter sent by him to one of his friends – a letter passionately appealing for assistance – he seems to have lived at 117 Fielden Street. In the interval between his previous visit in 1858 the poet’s wife had suddenly died, a loss which left him almost inconsolable, for with all his faults he loved her dearly, and this affliction, with the spectre of heart crushing, sole demoralizing poverty, which had haunted him more or less from the cradle, and which now menaced him more fiercely than ever, had brought him to the lowest states of wretchedness and despair.

Through the instrumentality of Mr. John Baron and other friends in Blackburn some little assistance was obtained for the poet from the Royal Literary Fund, but this was only of a temporary nature, and did nothing to place him above a permanent want. Prince finally quitted Blackburn in the months of August or September of the same year, and whilst there does not seem to be any record of further visits made by him to the town, he appears to have frequently corresponded with his friends and acquaintances there, many of his letters, it is to be feared, being urgent appeals for support. That he cherished in his heart a more than ordinary regards for Blackburn is evidenced from a letter he wrote to Mr. Carruthers, his former employer, a few years before his death, urgently soliciting work of any description and expressing a fervent wish to spend the remainder of his days in the town.

It was during his sojourn in Blackburn, in the winter of 1858, that John Critchley Prince wrote his famous poem, “The Angel of Temperence,” probably one of the finest and most intense temperance poems ever penned. Endowed with poetic genius of the highest order, generous to a fault, and beloved by all who came into contact, John Critchley Prince’s one besetting sin was that of intemperance. How much of this may have been due to heredity and early environment – his father was the victim of intemperance – or to the monotony of his occupation, and to his constant and increasing struggle with poverty, the student of his life will be the best judge. But unfortunately, the fact remains that so addicted was the poet to this vice, and to such a state of misery and degradation was he at times reduced because of overindulgence, that Richard Dugdale, a contemporary and brother poet, was constrained to say of him “Prince writes like an angel and lives like a devil.”

For a brief period, and when he was living at 34, Bent Street, Blackburn in 1853, Prince succeeded in throwing off the shackles which bound him, and through the influence of William Gregson, who, as previously stated who occupied the position of temperance missionary in Blackburn at this time, he was induced to sign the pledge, and it was under these circumstances, and whilst enjoying his emancipation from the drink fiend, that Prince wrote the poem, the original manuscript of which I have just secured possession of. The manuscript is clearly and well written, and though over sixty years of age, is in good condition. It bears upon it the inscription: “The Angel of Temperence” by John Critchley Prince. Respectfully inscribed to William Gregson, Temperence missionary.

The text, which commences with the line:

How fair is England in her lofty state

occupies four quarto pages. It is singularly free from erasures, only a few words and one whole line being crossed out with ink. In pursuing this poem there can hardly be any doubt left in the mind of the reader that the author, in depicting so vividly the horrors of intemperance, was reflecting some of his own sad and miserable experiences.

On the 5th May, 1866 – fifty years ago a fortnight hence – at the town of Hyde, in the fifty-eighth year of his life, bowed down with long sustained poverty and enfeebled in body and mind, John Critchley Prince, one of Lancashire’s sweetest singers, entered into that rest which had never been his portion whilst on earth. A simple stone, erected by a few admirers, marks his final resting place in St. Georges Churchyard, Hyde.

This article appeared in The Blackburn Weekly Telegraph in 1915.

Transcribed by Community History Volunteer, Philip Crompton, from a newscutting belonging to James Dunn retained with the manuscript for 'The Angel of Temperance' which is held in the James Dunn Collection at Blackburn Central Library.