Life-long Blackburn Rovers supporter Bob Snape recalls the experiences of a football fan in years gone by...

© BwD - terms and conditions

In terms of the football itself, there is nothing I can add to the several existing histories of Blackburn Rovers. The club’s fortunes have changed fantastically over the last forty years and everyone knows what happened after Jack Walker began to fund the club. However, it’s not only the football that has changed. The whole social setting of football has changed too. Each time I see black and white television snippets of football from the nineteen-sixties they evoke a different era, one that perhaps only came to an end with Rupert Murdoch and the Premier League. Half-remembered impressions of grounds, crowds and away trips now recall something I didn’t fully understand at the time, which was that the decline of the Lancashire town clubs was coinciding with the passing of the cotton era and the end of a way of watching football that had changed little since my grandfather was a boy.

My first visit to Ewood Park was the home match against Manchester United in February 1964. There was a long queue at the turnstile, and it seemed at first we would never get in to the ground. For the first few years I sat on the low benches around the perimeter wall where although the overall view wasn’t good, you were close to the footwork of the wingers. At half time it was possible to get the scores from other matches by consulting the board mounted on the perimeter wall opposite. On this, matches were indicated by letters and all you needed was the programme to tell which letter symbolised which match. Programmes from that period were advertising Dutton’s beers, Charles Buchan’s Football Monthly, Wood’s Textile Oil and London Midland football specials to away matches. Most people did not travel to the match by car. Trams had long since disappeared, but at the end of the match there was a convoy of Blackburn Corporation buses waiting to take people back to the centre of town. Others travelled by coach. At least five coaches went from Chorley and one picked up on the way. Up to ten people waited just at my pick-up point, the Heapey Busy Bee Co-op in Wheelton. Ribble Buses also ran a special football service from Chorley. Social mixing thus began well before the match and continued long after it, thus emphasising the communal experience of attending a game.

© BwD - terms and conditions

At this time football hooliganism was in a more-or-less dormant stage and the terracing was un-sectioned from the Blackburn end all the way round to the Darwen end. At half time the fans behind the goal used to exchange ends. Those standing on the Riverside, caught in the middle, were buffeted around a little when there was a big crowd, but there was no violence. However there were occasional bouts of madness, such as the time two supporters cleared the Blackburn end perimeter fence to attack the opposition goalkeeper. There were quite a few women at these matches –not many, but enough to notice. There was too a small number of girls in the Darwen End who could occasionally be heard to start their own high-pitched chant. Once, for a cup match against Arsenal, we sat in the Riverside Stand, a haunt so ancient, gloomy and lacking in any sign of the modern that it was all too easy to imagine that it was 1912 and Bob Crompton’s team were about to run out onto the pitch. The biggest crowd I ever saw at Ewood was on a freezing cold February night in 1969 for a several times postponed cup tie against Manchester City. Even until late afternoon it was not certain if match would take place, but the temperature remained just high enough and over 42,000 people turned up to watch Rovers go down to a 4-1 defeat. Older fans, having been in much larger Ewood crowds, will read this with mild contempt, but I remember this experience as mildly unpleasant and somewhat frightening. I was on the Blackburn End, unable to extract my cigarettes from my jacket pocket due to the pressure of people around. I don’t remember much about the match but I do recall thinking about my uncle who had been at Burnden Park in 1946 when the Embankment terracing collapsed with terrible loss of life.

From about 1967 onwards I began to attend away matches on a fairly regular basis. Matches in Yorkshire and the midlands were easily accessible by coach, but in 1969 my friend Sid and I decided we would make the journey down to Cardiff. This was before the motorway network and necessitated a Friday night departure from Penny Street. In Darwen the coach broke down and we all had to get off to push. There were no stewards or away travel clubs then, so it was perhaps inevitable that a stop somewhere down the A49 in Shropshire should result in some people on the coach becoming embroiled in vandalism. A policeman boarded the coach to say we wouldn’t be moving until this was sorted out and I remember wondering how I was going to explain a mass arrest to my parents. Somehow the issue was resolved and we arrived in Cardiff at 6.30 a.m. As our optimistic fellow-travellers leapt from the coach in search of an early-opening pub, Sid and I looked forward to some much delayed sleep on the coach. This wasn’t to be however, and we too were forced to wander the streets of Cardiff for almost nine hours until kick-off time. Most trips were less eventful than this, though Carlisle in winter was almost too cold to bear in some years. One which does stay in mind for the wrong reasons was a night trip to Burnden Park when, while seated in the coach waiting to set off home, we were attacked by a volley of stones and bricks. There was not one window left in the coach by the time the salvo ended.

© BwD - terms and conditions

Football doesn’t smell the same as it used to. Before smoking was considered to be anti-social, the football match was a place where you could puff away at your pleasure. Cigarettes, pipes and the odd cigar abounded and I remember being disappointed when the pipe I had surreptitiously bought on the strength of the sickly sweet smell of pipe smoke that hung over the Riverside terracing turned out to taste acrid and fiery and not a bit as I had hoped it to be. Another smell I associate with the old Ewood is that of recently consumed beer arising from the outdoor and uncovered men’s toilets at the Blackburn end of the Riverside. The closer it got to three o’ clock the more noticeable this was as latecomers fled the pub in the hope of making it into the ground for kick-off. The tea bars too had their own smell, not of grease as no frying took place, but of steaming urns of tea and coffee and of hot pasties and pies fresh from the warming oven.

The seventies were a thin period. Crowds became smaller and the possibility of promotion back to the First Division became more remote with each passing season. By the mid-nineteen seventies the club was in financial difficulties. A thriving army of supporters’ clubs carried the club through these dark days, unsung and unacknowledged. I was attached to the Chorley Branch which did magnificent work organising fund-raising socials and undertaking, week in week out, a waste paper collection, the receipts of which enabled the players’ wages to be paid. Things were that bad. At the first home match of the 1975-76 season I joined the rest of the Chorley lads in a sponsored walk from Chorley to Ewood to raise money for the club. There wasn’t even anyone there to say thanks when we arrived. At least the Rovers won 4-1 which was some sort of consolation. If things picked up on the pitch in the eighties, they couldn’t have been worse off it. Watching football through the mesh of a perimeter fence was the lowest point of my career as a spectator, a perverse reversal of a zoo where the fences protect the spectators; these were there to protect the players from us. It was sad that it took a tragedy to end this practice.

Watching football at Ewood is certainly more comfortable now as we are all seated. It doesn’t seem to be as exciting as it once was though – those muddy pitches and swaying crowds may have added to the atmosphere but I suppose the better surfaces and seating do make the game safer for those on and off the pitch The sense of freedom - to pay at the turnstile, stand where you wanted, move around if you wanted to change place - has been diluted, a process not helped by the armies of stewards, CCTV cameras and policemen (and women). The slow transformation from football supporter to football consumer is only a reflection of a general social trend for which football alone cannot be blamed, but something seems to have been lost on the way. The feeling that the club belonged to the people of Blackburn (always true in a cultural if not a financial perspective) doesn’t seem to be as much in evidence now that those convoys of buses no longer ferry fans back to the town centre at five o’ clock on Saturdays, but perhaps it’s as well that the geographical fan base of the club has widened. No enticing smells float around Ewood these days and having a permanent seat means you can’t move around and enjoy differing pockets of company. Still, when the Rovers’ No. 9 hits the ball into the opposition net, it’s Plus ca Change, Plus c’est la meme!

by Bob Snape

August 2004

© BwD - terms and conditions

On 5 November 1875, a meeting was held at the St Leger Hotel on King William Street to discuss forming a football club. John Lewis and Arthur Constantine, local business men and both ex-public schoolboys called the meeting for local townsmen with money, power and influence. As a result of this meeting of 17 well-educated middle class men, Blackburn Rovers was born.

Unlike today, football was originally a mainly upper class sport in England. Football clubs had first started in the 1820's, often in independent and public schools, each with their very own set of rules. Problems arose as each school had different ideas on the size of the pitch, how much handling of the ball was allowed, and whether or not hacking was permitted. When students moved onto university they needed a set of rules for the game so a standard code was drawn up. The Simplest Game, which had 10 rules, was established in 1862 and the following year representatives of English clubs formed the Football Association (FA).

© J. Burrow and Co Ltd - terms and conditions

Although the game of football, played under Association rules was still in its early days, Rovers played their first match, against the Church club, in December 1875. The match was reported by the Blackburn Times on 18 December and despite Rovers scoring first, the match ended in a draw.

Rovers' first ground was Oozehead. From there they moved to Pleasington Cricket Ground then onto Alexandra Meadows, all in the space of three years. In 1881 they moved to a new rented ground in Leamington Road. Their final move to the permanent site of Ewood Park, came in 1890 when the rent for the Leamington Road ground was increased. An all purpose sports ground that staged mainly athletics and dog racing, Ewood Park had a number of advantages. The tram line ran right outside, along Bolton Road, linking the ground to the town centre and railway station and it had also been used to stage an international match between England and Scotland in 1887. It was the natural choice for Rovers.

© LET - terms and conditions

Rovers quickly rose to fame. In the 1881-82 season they reached the FA Cup final, eventually winning the trophy in 1884. From then they won the FA Cup in 1885, 1886, 1890 and 1891. The team continued to flourish and became League champions in the 1911-12 and 1913-14 seasons. That period up until the First World War was a golden age for Rovers, an age that has never quite been repeated.

I first saw Ewood about the year 1866, when the members of an Oddfellows club turned out for procession and I, then a small boy, followed the music. Chief officials had a carriage and pair, some members rode on horseback, the rest walked. Each member wore a decoration or symbol, I suppose of the order.

As we approached Ewood one of the horsemen rode ahead to pay the toll-keeper at the toll-bar situated near the Albion Hotel.

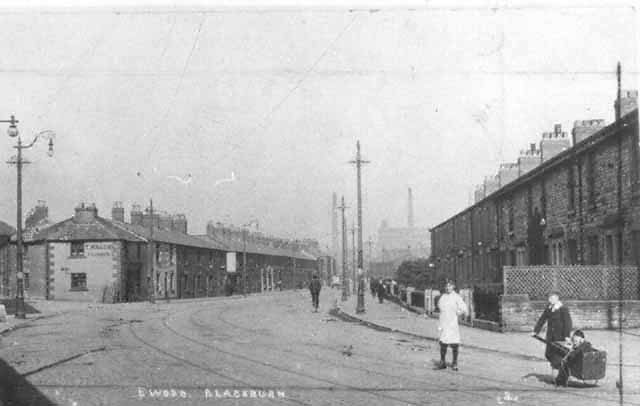

There had been changes at Ewood between 1866 and the time when I took land for building purposes at Ewood Bridge in 1887. The toll-bar had been abolished, the district had been incorporated into the Borough of Blackburn, steam tramcars had been introduced between Blackburn and Darwen, and the old saddle-back bridge over the River Darwen had been replaced by a new and wider bridge which was level with the road.

Ewood to-day takes in all the neighbourhood around Bolton-road reaching from Ewood Bridge to Craven Brow. The Ewood of centuries ago appears to have been confined to Livesey Township, and the Fox and Hounds Inn is supposed to have been the private dwelling or home of the people who owned and farmed the land comprising the Ewood estate, which came down to the river. Bolton-road cuts through the estate between Ewood Bridge and the Albion Hotel.

Long before I left Ewood some old lanes had disappeared. Before the bridge was put over the River Darwen I believe travellers forded the river a little above the present bridge, behind the Aqueduct Inn, and came to the other side of the river at the lower end of what is now called Calico-street. It was a lane which led up from the river to what is locally called the “Ash Pad.” It was this lane from the river leading in front of the Fox and Hounds which formed the boundary line between Livesey and Lower Darwen townships. Coming up from the river the toll-house stood in Livesey Township at the right-hand corner of the old lane and Bolton-road. The middle portion of the old lane which passed the Fox and Hounds was winding and dangerous, but was used until replaced by the new straight road which now connects Bolton-road and Livesey Branch-road. Fernhurst-street covers part of the old lane from Livesey Branch-road to the “Ash Pad.” The “Ash Pad” is the only part of the old lane that remains. It is now used as a footpath and is probably in about the same state of repair as it was three or four hundred years ago, when goods were mostly carried by packhorse. There used to be traces of another old lane on the left-hand as they came up from the river, before Bolton-road was reached. It ran along the left side of Bolton-road to about Tweed-street, and then turned to the right, probably leading to Fernhurst Farm and other places near by. It would cease to be used as a lane when Bolton-road was made, but, like many another old lane, it carried on as a watercourse, and the water flowed from it into the lane that is now covered by Calico-street, and then into the river.

© LET - terms and conditions

I understand that the houses on Bolton-road from Calico-street to Tweed-street had to be set back to keep clear of the watercourse, and thus allowed more garden space than usual in the district between the road and the houses.

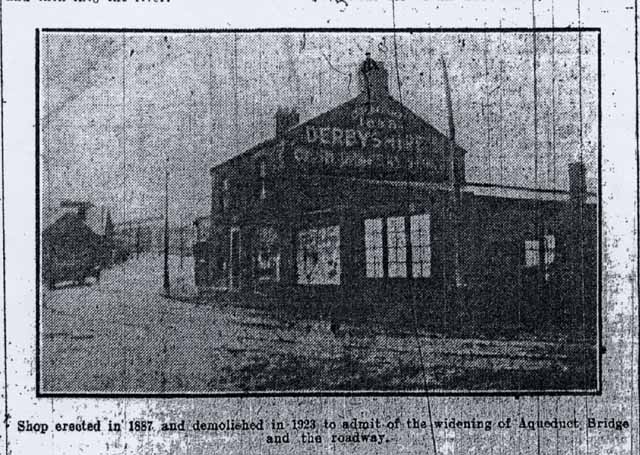

When the building (demolished in 1923 for street improvement) was erected on land at Ewood Bridge it was the only building on Bolton-road that was in Livesey Township. My next-door neighbour at the Aqueduct Inn on the one hand was in Blackburn Township, and on the other hand my next-door neighbour at the Albion Hotel was in Lower Darwen Township.

These parts on the border line of ancient townships had to be reckoned with in the old days, even after they were incorporated into the Borough of Blackburn. To the present generation they don’t matter now, when one general rate, including the poor rate, is levied for the township and County Borough of Blackburn, and when all registrars for births and deaths are conveniently housed at No. 4, King-street for all who live in Blackburn.

Hereabouts, in the old days, each township had its own poor rate collector and its own registrar for births and deaths, who were officials under the Poor Law Guardians. In this part of the newly-incorporated district the Guardians waited until these officials died off before they transferred the work to the central offices in Blackburn.

Early impressions led me to think that the man who got in the first got the business, for no sooner had I paid my poor rate to the Livesey collector than a collector from Blackburn came along with another demand note. This happened because the Blackburn collector was not aware that my premises were in Livesey Township. Lower Darwen poor rate had come into his hands but he had to skip mine when collecting on Bolton-road until the Livesey collector retired.

There was also confusion with regard to the registrar for births and deaths. My next door neighbour on one side had to register in an office in Blackburn and my neighbour on the other side had to go to the Darwen Registrar, while I, between the two, had to go to Witton to register the birth of a daughter, since deceased. When I called on the Registrar at Witton he refused to record her birth, saying he was not aware that my abode was in Livesey. After he made inquiry he was quite fair about it; he brought his book, registered the child at home, and said he had no authority to ask a parent to come twice.

The late William Livesey, one-time poor rate collector for the Livesey Township was the best authority I have met to tell of the boundary lines of the three townships in the Ewood district. He said half the land whereon the Conservative Club stands used to be in Livesey. The river, originally the boundary line between Blackburn and Livesey, had shifted its course and made inroads on the south bank, and left the original course on the north bank high and dry. The statement appeared to be borne out by an ordnance surveyor 40 years ago. The surveyor, after locating a well in a garden, where Messrs Robinson and Rishton’s workshop is now built, found the space between the wall and the river to be less than the space given on the old map. The meandering river had shifted its course by the action of force of bound and rebound when the water was in flood.

There was a time when amateur gardeners from Ewood became famous for winning prizes at horticultural shows. I understand they first won prizes locally, then they ventured further afield to Hoghton, Walton-le-Dale, Preston, the Fylde, and West Lancashire district. Show officials welcomed them as brothers in the craft. Each man got his proper name instead of his nick-name. Lords and the country gentry from such places as Knowsley, Skelmersdale, Latham and Winmarleigh, came along with their ladies to admire and wonder and ask how they achieved such results at Ewood. The locality at that time aided their intensive works and application.

Ewood, probably swampy ground for ages with occasional floods bringing loose matter from the moors to the rough herbage which grew and died down year by year, would in time become rich and fertile soil when cultivated.

The natural situation of Ewood contributed to the success. It lies in a hollow well protected from cold winds by higher ground around. The canal acts as a wind screen on the western side. The artificial stream locally called the “Sluice,” which was cut on the southern side of Ewood to carry water to Ewood and Stakes for bleaching and calico printing, incidentally contributed, along with the river, to the success those gardeners achieved. In the calm gloaming a vapour rose from the river and one from the sluice; the two vapours were attracted and met and then fell to the ground like a dew, at times when higher grounds were parched with the sun and needed rain.

Gardeners were successful when fish could live in river and sluice; while Ewood was a hamlet, Darwen a village, and the sunshine was uninterrupted by smoke and impurities in the air.

Gardens were situated in sheltered nooks along the river Darwen, and by the side of the sluice. Garden-terrace and the houses adjoining, opposite St. Bartholomew’s Church and school, stand on ground where once some gardens smiled. At that time there were trees on both sides of Bolton-road, which formed an avenue from Ewood mill to Craven Brow.

For years after, being out-distanced as prize-winners except near home, one old survivor held to his bit of land, his carefully-netted fruit bushes, and flowers in greenhouses. Often he sported a choice buttonhole and twiddled another between finger and thumb for a pal, when going to his work in the “devil room” at Thompson’s, Hollin Bank mill. No matter whether coming or going between mill and garden, his hurry and grim jaw gave a last-minute-no-time-to-bother-with-you air to his movements.

His lynx-like eyes missed nothing in a garden. He was alive to the unfolding of buds and flowers and appreciated their worth and beauty with a tenderness which showed another side to his character. There were times when his dark eyes sparkled and he became enthusiastic as he recalled some crowded hour of glorious life, when officials clasped his horney hand with a “Glad to-meet you again Mr. Crook,” when judges appraised his exhibits and when visitors admired and approved.

The above article was transcribed from the Blackburn Times of July 20th 1929

© BwD - terms and conditions

The article above tells about “Ewood before the Rovers” so when did the Rovers come to Ewood and how did Ewood Park come to Ewood?

The land that Ewood Park was built on was originally used for drying cloth dyed at Ewood print works and later as pasture land for cattle. In November 1881 four Blackburn business men acquired 14 acres of this land from Edward Petre (once Lords of the Manor of Rishton) for £5000. The area was enclosed by a large wooden fence, drained and re-turfed, a half a mile by 35ft race track was laid out and also a straight track measuring four hundred yards by 28 feet was laid down. The Blackburn Standard of April 15 says: “Horse boxes, dressing tents, a refreshment saloon, lavatories, etc., will be erected in a short time…A large and comfortable grand stand, with a natural elevation, will also be built and comfortable vantage ground will be afforded to all who attend the sports. The ground contains some pure spring water, and it is thought that if the sports prove successful probably baths will be built for the summer months. A platform for dancing will also be constructed, and the gentlemen who have purchased the ground are determined to do all they can for the comfort of the working classes, and offer them (every) possible facilities for enjoying themselves.”

The stadium was opened on the 8th of April 1882. The total cost of the building work was estimated at being £9,000.

On the opening day, the Blackburn Times said: “the weather was most favourable, though other attractions in the town influenced the attendance of spectators. However, there were 1,000 present, and considerable interest was manifested in the different events.”

The first events held were the heats of a 200 yards “dog handicap,” with a first prize of £20, second, £7, third £3. There then followed the heats for a 200 yards “foot handicap race”, the first prize being £20 and three other prizes of £5, £3 and £2, there were 21 competitors entered into the foot race.

The competition continued on Monday afternoon when 3,000 spectators turned up to watch the concluding rounds of the dog race and the foot race.

The winner of the dog race was “Cur” belonging to a Mr. Hopkinson from Tottington, and the winner of the foot race was W. Cummins of Preston.

Later in the afternoon a wrestling match took place for £20 between Alfred Aspen of Guide and John Clegg of Oswaldtwistle with Clegg coming out the winner.

In the following years Ewood Park was used for all kind of events including athletics, dog racing, trotting racing, and cycle racing, at one point it boasted one of the biggest and fastest cinder cycle tracks in the north. The Blackburn Michaelmas Fair was held there from October 9th to 19th 1885.

In 1890 the ground was taken on a ten year lease by the Blackburn Rovers Committee and the Rovers played their first match at Ewood Park against Accrington in front of a crowd of 10,000, the result being a 0-0 draw. Even though the Rovers had leased Ewood Park other events were still held there, such as the athletics festival of July 1891.

In 1893 it was decided by the Committee that they should buy the ground, and on Wednesday 24th January 1894 the papers reported:

“PURCHASE OF EWOOD PARK BY THE BLACKBURN ROVERS”

“Last evening the committee of the Blackburn Rovers Football Club completed the purchase out and out of Ewood Park, their famous enclosure. The club had already spent £3,000 on the ground, and they now propose to erect on the south side of the ground, where twenty additional yards of land have been purchased, a huge covered stand, which will make the ground the largest in England, and accommodation equal to nearly forty thousand spectators. The purchase money amounted to £2,000.”

On New Year’s Day 1896 the Rovers faced Everton at Ewood Park. During the game a part of the stand on the north end of the ground collapsed injuring about twelve people, a section of the crowd climbed over the rails on to the field. After the police had restored order the game continued with Everton coming out on top winning 3-2.

The Blackburn Times was the only local paper to report the accident but could only find room for a sentence. After a lengthy report on the match they finished with: “The collapse of the stand also affected the Rovers play, coming as it did when they were pressing.”

However The Leeds Mercury Thursday January 2nd 1896 gave a fuller account:

”COLLAPSE OF A STAND AT A FOOTBALL MATCH”

“Towards the end of the football match between the Blackburn Rovers and Everton, at Blackburn, yesterday, an open stand, on which were two thousand people, suddenly collapsed in the centre. For the moment a panic ensued among the spectators but the police were quickly on the spot and order was soon restored. Fortunately, not more than a dozen people were injured, and only three at all seriously. These were carried on to the ground and attended to.”

As this is not a article about the Rovers or Ewood Park I will finish here, suffice to say Blackburn Rovers became established at Ewood Park and went on to see good times and bad until the present day when they seem to be back to the bad…

by Stephen Smith Cotton Town Volunteer

© BwD - terms and conditions

The 1928 FA cup was played on Saturday April 21st. The finalists were Blackburn Rovers and Huddersfield Town, the white rose against the red rose as the newspapers liked to put it. By reaching the final they had taken the record for appearances in the semi-finals having played in thirteen, two more than Aston Villa. It would also be their seventh appearance in a cup final and their sixth time winning it, which equalled Aston Villa. It had been thirty-seven years since the Rovers had played in a FA cup final when they beat Notts County 3-1 in 1891. This was before the stadium at Wembley had been built and the game had been played at the Oval. It was not to be an easy road to Wembley for the Rovers and perhaps their hardest matches were to be against the lower division sides.

Below is Blackburn Rovers Road to Wembley. The sources for the match reports are the Blackburn Times and the Daily Mirror.

© BwD - terms and conditions

THE 3rd ROUND.

Rovers 4 V Newcastle 1; Played January 14th 1928

This was perhaps the easiest win the Rovers had throughout the entire cup. The Blackburn Times said, “it was the finest game at Ewood Park since the cup-tie with Tottenham Hotspurs in 1925.” After the first goal the game was never in any doubt and the Rovers made Newcastle look a second-rate team. Newcastle scored a consolation goal in the last minute, after a mix up in the Rovers' defence.

The scorers for the Rovers were, Puddefoot, Mitchell (2), Thornwell. For Newcastle, Seymour

The Teams were

Rovers

Crawford, Hutton, Roxburgh, Healless, Rankin, Campbell, Thornewell, Puddefoot, Mitchell, McLean, Rigby.

Newcastle

Wilson, Maitland, Hudspeth, Harris, Spencer, Gibson, Urwin, McKay, Crallacher, McCurley, Seymour.

The Referee was Mr. E.R. Westwood, Walsall.

The Gate was 27,052 with Receipts of £1,775.

THE 4th ROUND.

Exeter 2 V Rovers 2; Played January 28th 1928

Exeter were a third division team and what should have been an easy game turned in to a nightmare for the Rovers. The conditions at the ground were atrocious. The pitch was water logged, which made good football difficult. The Rovers had brought about 250 supporters with them; they would be disappointed. Rovers gradually started to get control of the match and Roscamp scored for the Rovers. Then in the 37th minute, after a strong tackle, Thornewell fell heavily on his left shoulder and fractured his collarbone. With only 10 men Rovers became disorganised and started to lose momentum, however they did manage to increase their lead. Two minutes before half-time, after a clearance, Hutton, had strong words with an Exeter player who he accused of kicking him. The referee awarded a free kick against him, there then followed a goal line scuffle and Exeter thought they had scored, but the referee waved play on. The linesman had been signalling and the referee stopped the match, after a consultation with the linesman he awarded a penalty to Exeter for handball by Roxburgh. Gee took the spot kick and scored. When the half-time whistle went, Rovers had a slender one goal lead. The second half saw Exeter dominating the game and the Rovers were under constant attack and were lucky not to concede a goal. After a foul by McLean, Mason took the kick and scored the equaliser, which they fully deserved. Soon after the full time whistle went with the match all square and a replay at Ewood Park to look forward to.

The scorers for the Rovers were, Roscamp, Rigby.

For Exeter, Gee (penalty), Mason,

The teams were:

Exeter.

Holland, Pollard, Miller, Ditchburn, Mason, Gee, Purcell, McDevitt, Dent, Vaughan, Compton.

Rovers

Crawford, Hutton, Roxburgh, Healless, Rankin, Campbell, Thornewell, Puddefoot, Roscamp, McLean, Rigby.

The referee was H.E. Grey London.

Gate 17,330, with Receipts of £1,781

THE 4th ROUND (replay)

Rovers 3 V Exeter 1; Played February 2nd 1928. (After extra time.)

In the first half the Rovers were playing against a strong wind. They were never on their best form with all the team playing well below par. Exeter played some good football and worried the Rovers. Both teams missed some good chances. Exeter scored first, in the 24th minute, when Compton’s corner kick curled directly in to the net. It took the Rovers just 2 minutes to equalise when Roscamp hit a shot that went under the Exeter keeper's body. After 90 minutes the score remained the same and extra time had to be played. It was now that experience showed and Rovers showed themselves the stronger side. Exeter began to flag as the game went on and Rovers scored 2 more goals. Exeter however had not made it easy for the Rovers, and they had struggled to get into the last sixteen.

The scorers for the Rovers were; Roscamp Puddefoot, Mitchell.

For Exeter; Compton.

The Teams were the same as for the previous match except the Rovers played Mitchell for Thornwell

Referee H.E. Grey London

Gate 28,348, with Receipts of £1,024.

© BwD - terms and conditions

THE 5th ROUND

Rovers 2 V Port Vale 1; Played February 18th 1928.

3,000 fans came to watch second division Port Vale take on the Rovers at Ewood Park, it was to prove another hard match for Blackburn. For the first 30 minutes the Rovers played the smarter football and in the 14th minute Roscamp scored from a cross by Rigby. Soon after this McLean, who the Blackburn Times says, “was never really fit to play, having travelled to the ground in a taxi after two days in bed with a high temperature and a septic throat,” missed a chance to increase the lead for the home side. Port Vale should have equalised when Antiss and Trotter between them missed a good chance. For the last 5 minutes of the first half Port Vale were constantly attacking the Rovers' goal and this continued after the break, however, against the run of play, after a foul on Puddefoot, Healless took the free kick, which was put into the back of the net by Mitchell to give the Rovers a much needed 2 goal lead. It took just 4 minutes for Anstiss to grab a goal back for Port Vale. From then until the end of the match Rovers were on the defensive and 10 minutes from time, with the Rovers defence in a tangle, Kirkham hit the upright with a tremendous shot. In the last minutes the Rovers managed to get in an attack, but Puddefoot could only manage to head the ball over the bar. Blackburn Rovers showed their relief when the full time whistle blew. Once again they had found the going tough against a lower division side.

The scorers for the Rovers were; Roscamp, Mitchell.

For Port Val;, Anstiss.

The teams were

Rovers

Crawford, Hutton, Jones, Healless, Rankin, Campbell, Roscamp, Puddefoot, Mitchell, McLean, Rigby.

Port Vale

Bennett, Maddock, Oakes, Smith, Connelly, Rouse, Anstiss, Kirkham, Littlewood, Page, Trotter.

Referee Mr. W Thomas, Willenhall.

Gate 43,000 with Receipts of £2,973.

© BwD - terms and conditions

Semi-final

Blackburn Rovers 1 V Arsenal 0; Played March 24th at Leicester

The Rovers came into this match as underdogs, but were full of confidence in their own ability to win it. Three thousand supporters followed their team to Filbert Road but were heavily outnumbered by the 10,000 who had come with Arsenal. The gate was somewhat disappointing with just over 25,000 people there. Some fans had climbed into the girders of the stands to get a better view.

When the game started, both teams played equally well but Rovers seemed to have more determination to win than Arsenal, Jones in particular played some good football, which helped keep the Arsenal attack under control. The heroes of the game however had to be the two goalkeepers. It was thanks to them that a lot more goals weren’t scored. In the first minute the Arsenal keeper collided with Rigby who badly injured his knee and for a short time it looked like he might have to go off. He managed to carry on and soon after had a great chance foiled by the defence.

The only goal came 4 minutes into the second half. After a poor pass from Buchan, Rigby intercepted and set off down the touchline. He crossed the ball into the centre where Roscamp was waiting. Cope for Arsenal had tried to put Roscamp offside but Butler in staying where he was kept the player onside. Roscamp ran through the centre and his shot gave Lewis no chance. For the next 25 minutes Rovers dominated the game with both Puddefoot and Rigby missing good chances. 10 minutes before the end Arsenal made a spirited fight back but it was to late, and with some great defending and brilliant goalkeeping from Crawford, the Rovers kept Arsenal out and booked their place in the final.

The Rovers' confidence had paid off. Some fans ran onto the pitch and managed to get to Crawford, hoisting him up, they carried him off the pitch as the hero of the hour.

The scorer for the Rovers was Roscamp

The teams were

Rovers

Crawford, Hutton, Jones, Healless, Rankin, Campbell, Thornewell, Puddefoot, Roscamp, Holland, Rigby.

Arsenal

Lewis, Parker, Cope, Baker, Butler, John, Hulme, Buchan, Brain, Blythe, Hoar.

Referee Mr. E.R. Westwood, Walsall.

Gate 25,633; Receipts £4,076

The other semi-final had been a different matter, Huddersfield, the firm favourites, were held 2-2 at Old Trafford and had to replay two days later at Everton. This match ended 0-0 after extra time and the next replay scheduled for a week later was to be played at Manchester Citys ground. Huddersfield finally managed to overcome Sheffield United by 1-0 and so the Rovers opponents were settled after 5 hours of Football.

© BwD - terms and conditions

Before the Final

The Rovers team left Blackburn on Friday morning. There were over 5,000 supporters, gathered around the station and Boulevard to see them off, with many of them losing a day's pay to see their team depart. The fans for the best part were in good order, but as soon as the team began to arrive, pandemonium broke out and the players had difficulty reaching the station. On the platform there were hordes of photographers as well as spectators. One particular fan, 72 year old Mrs. Catterall who was intending to leave for the match that night had brought a blue and white canary, housed in a blue and white cage, which she intended to take with her to Wembley and present to the King.

The train arrived at 10.47 and after a struggle the players managed to board. The Rovers' captain, Harry Healless, gave a short statement before the train left, he said, “You may rest assured we shall go all out for the victory, and I am hoping to bring the cup back to Blackburn on Monday.” The train pulled out of the station with the cheers of the crowds and loud explosions from fog signals, which had previously been laid, on the track. On arriving in London the players first went for a rest, before going to a local theatre. They stayed in the Russell Hotel, which had already played host to five previous FA cup winners. After a late breakfast, the team had a friendly game of golf while the chairman of the Rovers Mr. J.W. Walsh and the Mayor of Blackburn Mr. J.A. Ormerod JP, with others laid wreaths at the Cenotaph. The team arrived at Wembley in a closed coach about an hour before the kick off. In the dressing room they found many telegrams wishing them well for the match. Bob Compton and Harry Healless went out to inspect the pitch as the community singing was in full flow. The King and Queen now entered the Royal box. It was to be the first time the Queen had attended a FA Cup final. There were also the Duke and Duchess of York, representatives of the Football League, with the mayors of Blackburn and Huddersfield also in attendance. The National Anthem was sung and then the hymn 'Abide with Me'. With just a few minutes to go, the teams came onto the pitch. When it came to choosing the final colours for each team a problem arose, as both teams played in blue and white tops. The FA had decided on the previous Wednesday that the Rovers should wear dark blue shirts with white shorts while Huddersfield would wear white shirts and dark blue shorts. The Rovers had the town crest sewn on to their shirts. The captain Harry Healless led the Rovers on to the pitch, while Huddersfield were led by their captain, Stephenson. The King and Duke of York came on to the pitch and were introduced to the players and officials. Things were now set for the 1928 cup final to kick off.

© BwD - terms and conditions

The Final

Blackburn Rovers 3 V Huddersfield Town 1; Played April 21st 1928 at Wembley.

Once again Blackburn Rovers were the underdogs and apart from their own fans, almost everyone gave Rovers little chance of winning this match. Huddersfield won the toss and chose the end to play from giving Blackburn the kick off. Within a minute, to the surprise of everyone in the stadium, the Rovers scored the first goal. Blackburn had won a throw in on the half way line; the Daily Mirror goes on to describe the goal thus. “On the half way line Healless, the Rovers right half-back threw the ball in. It went to Thornewell, who found himself challenged by Barkas. Thornewell centred over Barkas’s head and Mercer caught the ball just as Roscamp dashed up and charged him. The ball rolled out of Mercer's hands and into the back of the net.” Almost as soon as the game restarted the Rovers had another chance of scoring, the defender Barkas tried to pass back to Goodall, who missed the ball. Roscamp got on to it. The goalkeeper tried to kick it clear but without success, by then Goodall had recovered and cleared it. For the next 15 minutes the game was all Rovers, for 9 minutes Huddersfield didn’t get a touch of the ball and it was 12 minutes before they could mount their first attack. After that Huddersfield started to settle into the game and were unlucky not to score, after Kelly sent a shot just over the bar. Both sides were now playing good football and both sides had their fair share of chances.

Blackburn’s second goal came when Rigby got away from Redfern and passed to Roscamp. Roscamp returned the ball to Rigby who crossed it to McLean. The Huddersfield keeper came out, but could do nothing to stop the shot. Rovers were 2 up. Huddersfield were again unlucky, with shots from Kelly and Smith just going wide and for the Rovers, Roscamp and Puddefoot both came close. When the half time whistle went, Rovers were holding onto a comfortable lead.

At the start of the second half Roscamp nearly scored again, as he had in the first half, with the Huddersfield defence in total disarray, he could only shoot wide. It now started to rain, making the pitch slippy and the game looked as though it might fizzle out. However after some good play by Huddersfield, Jackson who had changed position with Kelly hooked onto the ball and went for goal. Crawford could not hold onto the shot, and it rolled out of his hands and into the net. This goal brought new life to the game. Huddersfield’s captain Stephenson came close to equalising when he headed a cross from Smith. Both sides had good chances of scoring. One attack saw Roscamp get the ball past Mercer and into Huddersfield’s goal, but the referee, who had an excellent view of the play, blew for off side and despite protests, the goal was disallowed. With just 4 minutes to go Roscamp ran through the defence, beat Mercer and hit the ball into the corner of the goal, giving the Rovers an unassailable lead. At the final whistle, against all the odds Blackburn Rovers, who had played the better football had won the FA cup for the 6th time in their history, equalling Aston Villa's total.

The scorers for the Rovers were; Roscamp(2), McLean

For Huddersfield Jackson.

The teams were

Rovers

Crawford, Hutton, Jones, Healless, Rankin, Campbel, Thornewell, Puddefoot, Roscamp, McLean, Rigby.

Huddersfield Town

Mercer, Goodall, Barkas, Redfern, Wilson, Steele, Jackson, Kelly, Brown, Stephenson, Smith.

Referee Mr. T.G. Bryan, Willenhall.

Gate 92,041; Receipts £23,238.

© BwD - terms and conditions

After The Final

Captain Harry Healless led Blackburn Rovers up to the Royal Box to be presented with the cup by the King. Congratulating him the King said how much he had enjoyed the game, particularly the first half, and that the best side on the day won. He then presented the rest of the team with cup-winning medals. The players shook hands with the Queen and the other dignitaries' before going back to the pitch to start the celebrations.

On their way back to the Russell Hotel, the team travelled with the cup in an open top “charabanc.” The route was crowded with cheering spectators. Back at the hotel a celebration dinner had been prepared for over a hundred guest. All the tables were decorated with blue and white and the waiters wore blue and white rosettes. On the table besides the cup was an illuminated ice ornament of a footballer kicking a ball into the goal. The players were presented with horseshoes. Sunday, the day before they were to return home, the team went on a drive to Windsor, where they listened to the Guards band playing and relaxed.

On Monday the team left London for the return trip to Blackburn. When the train arrived at Crewe, a large crowd had gathered to see them and especially Rigby, who was a former player for Crewe Alexander. From Warrington crowds were at every station to wave and cheer them on their way. They left the train at Preston station and completed the rest of the journey by road in an open top coach. The motorcade, which accompanied them, was almost a mile long. Supporters had gathered right from the Boundary at Yew Tree and the vehicles had to slow to a snail's pace to avoid accidents, as the crowds had spilled out on to the road. A band played “See the Conquering Hero Comes,” while Healless sat at the front of the bus holding on to the cup. The blue and white canary belonging to Mrs. Catterall had somehow found its way into one of the coaches and was being held up for the crowds to see. People were climbing lamp posts and tram standards. They sat on roofs and chimney to get a better view of their team, and the noise was unbelievable. The club colours had been strewn everywhere, blue and white confetti was being thrown. When they reached the bottom of Preston New Road, the crowd was estimated to be 150,000. Sudell Cross was to be the start of the parade through Blackburn. As the convoy turned on to Limbrick, many people were crushed, but no one was seriously injured. It was reported however that there were over 300 cases of fainting. Similar scenes were reported along Randal Street and Whalley Range. The parade then turned at Bastwell and made its way down Whalley New Road on to Penny Street. Waiting for them at Salford was the biggest crowd yet. Their passage was slow and the police had their work cut out preventing accidents. From Salford they went onto Railway Road, Jubilee Street and then Darwen Street. When they reached King William Street, they found their way blocked and a detour via Northgate, Sudell Cross and Richmond Terrace was made. They finally reached Tacket Street and the Town Hall. Owing to the vast numbers at the front of the Town Hall, the players had to be virtually smuggled in at the back door. Inside the team were taken to the council chamber for a civic reception and presented to various officials of the town. The team then came out onto the balcony with Healless and the Mayor holding the cup. Then the band stuck up “Abide With Me” and was accompanied by over 40,000 voices. It was late when the players finally left the Town Hall and they had to abandon their original plan of travelling through Witton and on to Clevelys, instead they took the more direct route and went by Preston New Road to the disappointment of vast numbers, who were lining the route along Redlam and Witton. It was late when the town started to settle down, with many people happy, tired, with the prospect of a day's work ahead.

It was not until 1960 that cup fever hit Blackburn again. That year saw them in the final against Wolverhampton Wanderers, which they lost 3-0

Since then the Rovers have won the Premiership Trophy and were crowned Champions of the Premier league at Anfield in 1995. They lost the game to Liverpool 2-1, but Manchester United, who could have won the championship themselves, could only manage a draw against West Ham and so lost out to the Rovers

.

On February 24th 2001 the Rovers won the Worthington Cup 2-1 against Tottenham Hotspur at the Millennium Stadium, Swansea. Once again the Rovers went into the game as underdogs and, like 1928, pulled off a great victory for the town.

By Stephen Smith, A CottonTown volunteer

by Diana Rushton

© BwD - terms and conditions

Blackburn Rovers Squad 1889-90

Back row from left to right: Jas. Southworth, John Southworth, Mr. M. Birtwistle (Umpire), J.K. Horne, Geo. Dewar.

Middle row from left to right: Jos. M. Lofthouse, Harry Campbell, John Forbes (Captain), N. Walton, Wm. Townley.

Front row from left to right: John Barton and Jas. H. Forrest.

The Blackburn Rovers team of 1889-90 faced Sheffield Wednesday in the 1890 Cup Final. Played at the Kensington Oval, now more famous as a cricketing venue, they won by the narrow margin of 6-1! Billy Townley scored the FA Cup's first ever hat-trick.

© BwD - terms and conditions

Presentation of players to H. M. the King. 1928 FA Cup Final.

The Rovers players and officials meeting King George V, prior to the start of the 1928 FA Cup Final. My claim to fame is that my Great Grandfather, John A. Ormerod was Mayor of Blackburn at this time and sat next to the King!

Sadly the Rovers have never managed to achieve greatness in the Cup Final since 1928. Their only other appearance being in 1960 when they lost 3-0 to Wolverhampton Wanderers.

© BwD - terms and conditions

Jubilation in the dressing room as Rovers beat Huddersfield Town 3-1 in the 1928 FA Cup Final.

Jubilant players celebrate their triumph in the FA Cup Final of 1928 against Huddersfield Town.The Rovers were very much the underdogs as Huddersfield's team included several internationals and they were at the top end of the League, whilst Rovers were nearer the bottom.

The final score was 3-1, with Roscamp scoring twice. The other goal was scored by McLean.

The players in the shot are:

Front (l-r) Jock Hutton, Harry Healless(captain with the Cup), George Thornewell, Arthur Rigby, Peter Holland.

Back Bill Rankin, Tommy Mitchell,Herbert Jones, Jock Crawford, Tommy McLean.

© BwD - terms and conditions

Early 1900s Football Memorabilia

Modern football prima donnas would not be seen on the field in anything other than ‘Play Dry’ technology shirts, golden boots and jewellery with a market value higher than most of us earn in a year.

Step back a century or so however and the Versace play wear of yesteryear consisted of heavy woollen shirts (imagine what they would have been like to wear in the wet), hob nail boots and anyone sporting body piercing would have been abused by the crowd and shouted from the field. How things have changed!

© LET - terms and conditions

Fergus Suter

Fergus or Fergie as he was known, is famous as the Rovers first professional player.

Born in Glasgow, he was a stonemason by trade. He played for Partick Thistle and Glasgow Rangers before coming to Lancashire. He began his career "south of the border" at Turton in 1878, moving on to Darwen the following year.

He gave up his career as a stonemason claiming that English stone was to hard to work with! Rumour has it that Darwen were paying for his services. Moving on to Blackburn Rovers in 1880 he was to remain with the club until 1889.Whilst playing for the Rovers he was employed as a tape sizer at a cotton mill.He appeared in four FA Cup Finals whilst with the Rovers.

© LET - terms and conditions

William Gladstone: Rovers Supporter!

In the hours of darkness, high spirited Rovers fans adorn the statue of William Ewart Gladstone with a scarf and hat.

The 3 ton statue was originally unveiled on Blackburn Boulevard by the Earl of Aberdeen on the 4th November 1899 with a crowd of 30,000 onlookers. The statue was the first statue erected in Great Britain to commemorate the life of the great statesman and now resides outside King George's Hall after being removed from the boulevard in 1955.

When the subject of football disasters is brought up, many people immediately start talking about Hillsborough, Hysel, Ibrox, maybe even Bradford but there is one disaster which is never mentioned, probably because it didn’t occur at a football ground but the people who were there will never forget it. I am talking about the railway bridge collapse at Bury in January 1952.

© BwD - terms and conditions

It was the 19th January 1952 and thousands of Blackburn Rovers fans had just enjoyed a 2-0 over Bury at Gigg Lane and were due to head back home on the train and were waiting for four special trains to arrive at Knowsley Street station. One train had already filled up and left the station and more than 200 supporters were waiting on a wooden bridge ‘packed like sardines’ for the second train to arrive when they heard a creaking, then a crack. Suddenly the bridge collapsed and the supporters fell 20 feet on to the track along with debris from the fallen bridge. Some people who had escaped the bridge collapse actually fell through the gap left by the bridge as the crush of people was so great. The leading porter, David Foulkes, saw what had happened and immediately sent out an ‘obstruction danger’ signal in all directions. His swift action saved many lives as one train stopped just 200 yards from the injured.

Men, women and children were scattered along the track along which a train could pass at any moment. There was no lack of volunteers to go to the assistance of the injured. Some Rovers fans, including a young Jack Walker, scrambled down on to the tracks to help pull the injured people free. Jack recalled the event in an interview in 1992. “I was on the bridge with my brother Fred, but we didn’t go down. We were at the other end. There were thousands of people trying to get on the bridge, then suddenly it started vibrating, rumbling and shaking and then the middle just dropped out. It was frightening. We went down on to the railway line and Fred and me helped get helped get people off the tracks – including the mascot.”

© BwD - terms and conditions

Other supporters also described their experiences, Mr James Smith, a lathe operator at the R.O.F. talked of ‘a sudden crack and the whole floor went down beneath our feet’, one of the youngest victims, 14 year old Blackburn Grammar schoolboy George Haworth, described how his friends only escaped the crash because he had lost his return ticket home. Jack Squires, aged 23, fell along with his father Raymond and afterwards grinned ruefully after telling reporters how he had only just recovered from hurting his back in a fall through a garage room a few weeks before. Another man, Harry Steele, a shop foreman for Foster, Yates & Thom, was also a witness of the disaster at Bolton in 1946. Mr George Kay from Furness Street remarked laconically ‘The Rovers picked up points at Bury and we dropped on some’.

The Fire Brigade arrived just six minutes after the incident and the Police arrived 5 minutes after that. Waiting rooms became casualty clearing stations and 30 ambulances and a number of buses arrived from Bury to act as a makeshift shuttle service conveying the injured to hospital. The last casualty was removed from the scene at 6.15pm. As the victims were brought into the hospital, faces blackened with dust and soot, local clergymen, hearing of the disaster, were there to help comfort the injured and offered cigarettes and tea. Operating theatres worked through the night and some of the injured were sent to the Royal Infirmary and Queen’s Park Hospitals in Blackburn.

© BwD - terms and conditions

Relatives waited outside Blackburn station on Saturday night and about 9.30pm two Rochdale double-decker buses arrived containing about 30 of the injured. They were transferred to Blackburn Corporation buses, manned by personnel who had finished their normal duties and volunteered to help with the emergency. Some of the others were taken straight home by ambulance. On the Sunday afternoon the Town Clerk, Mr C.S. Robinson, at the request of the Borough Police, authorised the provision of a special bus to convey relatives to Bury Hospital to visit their loved ones.

© BwD - terms and conditions

One person, William M Hargreaves, died in the tragedy and 175 people were injured, 56 of which had to be detained in hospital. They were visited by the Mayor Alderman William Hare and the Town Clerk, Mr C. S. Robinson. Officials and players from the Rovers, including Captain Bill Eckersley also visited the injured. Blackburn Rovers also arranged collections to be taken at the following home game against Luton Town in order that the injured might be provided with ‘additional comforts’.

© BwD - terms and conditions

William M Hargreaves, a widower and a retired weaver, aged 66, died in the tragedy and 175 people were injured. William was with three other friends at the time, he received injuries to his chest and back. He was described as a keen Rovers supporter, a season-ticket holder and always travelled to away matches. He lived with his son-in-law and his wife in Havelock Street. His wife passed away four years previously when he was living in Princess Street. Witnesses reported seeing Mr Hargreaves lying under another injured man with a heavy wooden beam pinning them both to the rails. He was rushed to hospital and he described the accident as “a nasty mess” but could not give a full account of what happened to him. He passed away at Bury General Hospital on the Monday night. Mr Hargreaves officially died from lobar pneumonia following chronic bronchitis and shock after rib fractures.Among the floral tributes was a wreath from the Directors, Officials and Players of Blackburn Rovers, in the blue and white colours of the team he supported with such enthusiasm for many years. Other wreaths were from the Green Park Veteran Bowler’s Association of which Mr Hargreaves was a member. Only members of the family attended the funeral service and the internment was at Pleasington Cemetery.

There was an immediate outcry for an investigation into the tragedy and Bury Town Council held a special meeting on the Monday to discuss the matter and formulated a request to the Ministry of Transport for a public inquiry. On the Tuesday senior officials from British Railways conducted an on-the-spot inquiry and it was announced that Brigadier C. A Langley would conduct the public inquiry which took place on the Tuesday 30th January at the Divisional Offices of the Midland Region of British Railways at Hunt’s Bank in Manchester.

© BwD - terms and conditions

At the inquiry, it was discovered that the bridge on which the tragedy occurred was about 70 years old with a span of 60 feet 9 inches long, 7 feet 4 inches wide and although it was described as ‘an unusual construction’ it had passed inspections in 1944, 1946 & 1948. The Brigadier congratulated all concerned who helped with the injured on site and the Bury Hospital staff on the way they dealt with the emergency. A consultant engineer, Mr Arthur Cresswell, blamed the collapse on the lack of proper maintenance saying that “I would be surprised if the bottom boom of the bridge has been inspected in the last 25 years. Mr A Tims, a Blackburn contract engineer, said that the bridge was inspected in 1944 by a joiner, a man who had since died but from his report there was no immediate indication that the bridge was in a dangerous condition. He had taken the boards of the inside of the bridge but not off the outside. He did not take off the outside boarding because it was wartime and there were staff difficulties. The inspection in 1946 was carried out by a Mr Halewood during a time when the bridge was being repaired. It was having a new roof put on to the bridge, and the outside and inside boards were taken up, along with the floorboards. Mr Halewood looked at the straps at the bottom of the bridge by climbing up a ladder with a hammer and said that they were all right. It was also inspected in 1948 by another man, also since deceased, and his report requested that the outside boarding be replaced as well as outside down spouts and facing boards. None of these recommendations were believed to have been carried out. It was revealed that the man who carried out the inspection in 1948 was in fact a bricklayer, but it was agreed that he should have noticed any corrosion on the bridge.

© BwD - terms and conditions

Mr F Turton, bridge and steel work engineering assistant, said he had examined the bridge work since the accident and had made calculations as to its strength. It would have capable of holding a full load if it had been in good condition. He reckoned that the corrosion of the straps had taken approximately 10-15 years to develop. It was believed that the straps would have been covered with soot and unless they were thoroughly cleaned it may have been difficult to see just how corroded they were. Brigadier Langley told Mr Turton that he wanted further tests on the straps to ascertain their condition.

After the 9 hour hearing, the inquest jury reached their verdict of ‘misadventure’ and in their opinion there had been no adequate inspection of the bridge for a number of years. It was found that the failure of the wrought iron straps at the bottom of the bridge had caused the collapse. All similar bridges were inspected and eventually replaced. It was a tragedy that most people outside Bury & Blackburn have never heard of, and even in those towns it is spoke of very little when people recall football tragedies, but any loss of life should not be forgotten, whether they support Liverpool, Juventus, Bradford or Blackburn Rovers, especially when all that person was doing was following his favourite football team.

by Roger Booth

Blackburn Rovers Full Members Cup

Victory Parade (Radio Lancashire, 30th March 1987).

A three coach convoy, led by the

players’ open top bus, travelled from Ewood Park, where fans had already

gathered, along Bolton Road to attend a civic reception at the Town Hall. The convoy stopped outside Blackburn Royal

Infirmary, where the players alighted and showed off the Trophy. Patients waved from the windows, and nurses

lined up along the grassy bank to cheer the team. Some fans ran alongside the

coaches on the journey into town.

Various voices can be heard,

including Glenn Keeley, Terry Gennoe, Don Mackay, Tony Diamond, Chris Sulley,

Alan Ainscow, John Haworth (Club Secretary), Mike Madigan (Mayor), Simon

Garner, Paul Mckinnon, William Fox (Chairman), Colin Hendry, Jim Furnell, Scott

Sellars, William Bancroft (President), Ken Beamish, Keith Hill, Ronnie Clayton,

Bryan Douglas, Jim Branagan, Noel Brotherston, Chris Price and Mike

Rathbone.

Outside Blackburn Town Hall, fans

scaled every vantage point to see their heroes.

Coverage of this triumphant

occasion was given a sense of perspective with an interruption by a newsflash,

naming a Preston soldier killed in Ireland while serving in the Queen’s

Lancashire Regiment.

53 mins 14 secs.