A photograph of members of Darwen Cricket Club.

So, how long does it take to become proficient in the art of this gentleman's game, called cricket?

Does it share equal status with the other old Royal and ancient game, called golf?

It is generally believed the game of cricket was not played outside the British Isles until the Britons themselves introduced it to the natives of many lands that make up the British Empire, upon which it has been said, the sun never sets.

Proclaimed as the National Game of England, 32 other countries are members of the International Cricket Council, located in London. The rules that govern the game all over the world are those drawn up by The Marleybone Cricket Club (MCC) in about 1788.

A medal awarded to Esau Bury for cricket, inscribed with his surname and initials and the initials of Darwen Cricket Club.

The game was introduced to the American colonies in the mid-18th century but never achieved widespread popularity in the United States.

Naturally, one suspects that the game has been played since that time in every corner of England by every generation of 'gentlemen'. I use the term loosely, as from time to time, it would appear to the casual observer that quite the opposite may be the case. The game is said to build character, courage and determination. To stand steadfast in the face of imminent danger, and to protect your wicket at all cost is a feat, if it can be achieved, that is held in the highest regard by those peers of the person achieving.

At first, those unfamiliar with the game may be forgiven for thinking that by a strange quirk of fate, they have happened upon some medieval ritual. Those relaying a description of the game to others not in the vicinity, use terms such as 'hitting the ball down to long on', or 'driving it through the covers', and 'he trickles the ball down into the gully'. A batsman is 'out' if the ball leaves the bat and is 'caught in slips', by those other men who are 'in the field', and who, incidentally are called 'fieldsmen.'

Another puzzling term is when a bowler is said to bowl a 'no ball' and the batsman, if he is quick enough, can belt it and still make a score! When a fieldsman is at 'silly point', he is almost within striking distance of the batsman's bat. This term then is self descriptive.

A batsman has to 'go in' before he 'goes out', and he can score without hitting the ball with the bat if the ball strikes his leg and it runs out into the field. This is called a 'leg bye'. If it hits him in the head, is that called a 'good bye?'

The bowler's objective is to 'break' the wicket, which are three round sticks, with grooves in the top which stand upright in the ground.

Two small specially shaped round wooden cylinders, called 'bails' lie in those grooves, along the top of the vertical sticks. A batsman who gets out without scoring a run is said to have 'made a duck'.

The man standing behind the wicket and the batsman is referred to as 'the keeper', no doubt something to do with the wickets resembling bars of a small cage. Perhaps this is where the keeper keeps all the ducks.

A medal awarded to Esau Bury in 1905 for cricket, inscribed with his surname and initials and the initials of Darwen Cricket Club.

No doubt you have to be a certain kind of person to play cricket, and whilst my own experience is very limited, (highest score, 11 runs), that was my major achievement on the cricket field, preferring to leave the more highly technical and academic details in much better and more experienced hands.

So it came as rather a surprise to learn that one of our early ancestors had been associated with this rather fascinating game at a higher level. Evidence has come to light indicating without doubt definite associations with the Darwen Cricket Club, near Blackburn in Lancashire, England.

A photograph of Esau Bury, the elder brother of John William Bury, grandfather of Norman Bury who won medals as a member of Darwen Cricket Club.

An old photo of Esau Bury and his family, together with some medallions, were kindly forwarded to me by two more recently discovered relatives, Mr Frederick Devine, and his sister Joan, who are in fact cousins of mine. Esau Bury is the older brother by six years, of my grandfather, John William Bury.

The front of a medal won by Esau Bury in 1904 for cricket, it is engraved with the initials of Darwen Cricket Club.

The medallions have been inscribed during consecutive years 1903, 1904 and 1905, with his initials and surname together with the initials of the Darwen Cricket Club and the above dates. If there is any one out there who knows of any records of the Darwen Cricket Club going back as far as the above dates, then I would very much appreciate hearing from you. Mr Frederick Devine has already made some considerable efforts on my behalf, to raise further information, but as yet, to no avail.

(Acknowledgement to Encarta 98) Norman J. Bury 12/02/04

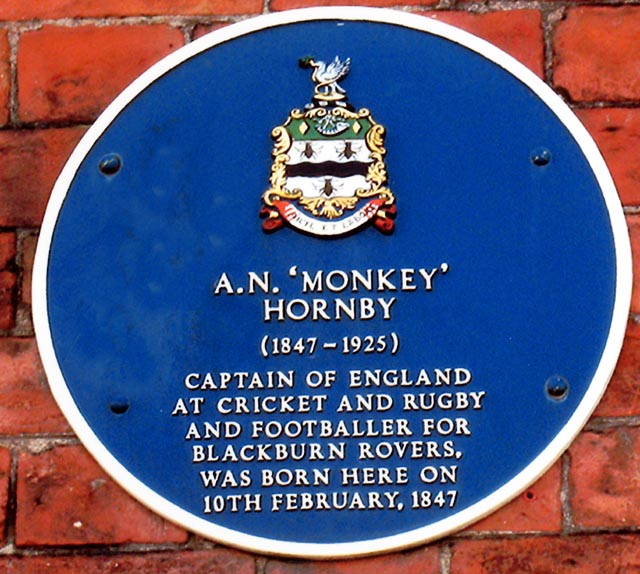

Albert Neilson Hornby was born in Brook House, Blackburn on the 10th February 1847. He was the sixth son of William Henry Hornby, M.P. for Blackburn 1857-69, the First Mayor of Blackburn and the Director of the Lancashire & Yorkshire Railway. He was educated at Harrow School and while he was there he played for the cricket team and played against Eton at Lord’s, opening the innings and scoring 19 and 27 runs in his two innings. He was only five feet three inches in height at this time and six stones “bat and all“which led to him acquiring the nickname “Monkey” because of his small stature and boundless energy. While he was at Harrow his family moved to Shrewbridge Hall in Nantwich, Cheshire. After a brief spell at Oxford University he returned to join the family business in Blackburn. He first played for the Cheshire cricket team in 1862 and played in over 20 matches for them, scoring 1672 runs, including 201 against Shropshire and taking 39 wickets.

He played his club cricket with the East Lancashire Club in 1867. In June 1868 he was one of the Eleven Gentlemen of the East Lancashire Club who played the Australian Aboriginal Eleven at Blackburn. He took 4 wickets in the first innings and 5 in the second, scored 117 runs opening the batting for East Lancs. Unfortunately the match was drawn with East Lancs needing just 2 runs with 9 wickets in hand. In 1870 he scored a massive 213 not out against Accrington and in 1872 against Burnley the match was abandoned. Hornby was practising near the scorer’s tent and when the umpire asked him to stop, he responded in such a way that the umpire retired from the game.

Hornby's first match for Lancashire was in 1867 against Yorkshire at Whalley. He only scored 2 and 3 when he opened the batting and the team lost by an innings and 56 runs. In 1870 he scored his 1st first-class century, 132 against Hampshire at Old Trafford. The secretary of the M.C.C. included Hornby in a select amateur side to visit North America in 1872. The side included the legendary W.G.Grace. In 1879 Hornby became Lancashire captain, succeeding fellow opening partner Richard Barlow, and holding the position for 12 years. He became president of the club in 1894.

In 1876 he married Ada Sarah Ingram, the daughter of Herbert Ingram M.P. of Rickmansworth, founder and proprietor of “The Illustrated London News” and set up home in Nantwich.

He was renowned as an all-round sportsman. He kept a stable of up to a dozen horses in Cheshire, was a useful boxer and played Rugby well enough to be capped by England nine times between 1877 & 1882. He was also Captain of England in 1882. He later refereed at Rugby and was a member of the Rugby Union Committee. At football he played for Blackburn Rovers and later became President of the Lancashire Football Association.

Late in August 1882 he captained England in the famous Test Match against Australia at the Oval which the Aussies won by 7 runs. He scored only 2 and 9 runs in his innings but was much praised for his intelligence use of his bowlers. Fred Spofforth, the Australian’s finest pace bowler of the 19th century was Englands nemesis, taking 7 for 46 and 7 for 44 (see next page for more on this test match). Although he captained England in it's most famous test match ever, he only played in 3 test matches for England, scoring 21 runs at an average of 3.50, his top score being a miserly 9.

In 1881 he became the first Lancashire batsman to score 1000 runs in the season and at the age of 50, in 1897, he returned as Captain of Lancashire and lead them to their first outright Championship since 1881. He continued as President until 1916 and regularly attended matches at Old Trafford right up till his death. His portrait hangs in the long-room at Old Trafford. He died at Parkfield, Wardle in Nantwich, Cheshire on 17th December 1925, aged 78.

His son, Albert Henry, also played 283 matches for Lancashire and was captain from 1908-1914.

A.N. Hornby was buried at Nantwich, where his tombstone bears the image of bat, ball and wicket. A plaque is situated at 41 King Street, the birthplace of Arthur Neilson Hornby.

The legend of Ashes cricket started in August 1882 at The Oval in the London suburb of Kennington. On Monday 28th August England fielded a strong team, which included W.G. Grace. England had never been beaten at home previously and the Australians were given little chance of beating the star-studded English. Hornby lost the toss, and Murdoch the Aussie Captain was delighted to bat first as the Oval pitch was expected to deteriorate as the game progressed. Massie and Bannerman opened the innings for Australia but the morning’s play turned into a disaster for the Aussies as at one time they were 30 for 6. Twenty minutes after lunch Australia were all out for 63 runs. Barlow was the star of the England bowling attack, taking 5 for just 19 runs in 31 overs (4 balls an over at this time), 22 of them maidens.

For the England reply, Hornby decided that his batting line-up was so strong that he put himself No.10 on the batting order. He reckoned without Fred “The Demon” Spofforth, already a star of the game, he became the first man to take a Test hat-trick and to claim 10 wickets in a match. He took the first two England wickets with only 18 on the board. However, England dug in and reached their opponents total with 4 wickets in hand. Hornby came in on 96 and took England past the Century but fell to Spofforth for 2 and they finished with a lead of 38 runs. Fred Spofforth ended with figures of 7 wickets for 46 runs. Although the Australians were anxious about the task ahead they took heart that England had missed opportunities to make a much bigger score.

On the Tuesday, a heavy downpour delayed the start but on resumption Australia started brightly and soon the arrears were wiped off. The pressure increased when Lucas dropped a easy chance from Massie which cost England nearly twenty runs. After several bowling changes, inroads were made into the Australian resistance and they completed their innnings on 122 runs on the scoreboard, a lead of just 84.

The atmosphere was tense during the 10 minute interval between innings and the Australians desparately tried to hatch a plan to bowl England out. It was Fred “The Demon” Spofforth, the scurge of England in their first innings, who provided the catalyst for what was to follow by bolding declaring “This Can Be Done!”. Hornby decided to open the innnings this time with W.G.Grace but was bowled by Spofforth with the score on 15. When he bowled Barlow next ball for 0, the crowd went silent, the Austrailans sensing victory. However, Grace and Ulyett made a stand of 36 and from England’s point of view defeat was unthinkable, only 34 needed with eight wickets in hand. Then Ulyett was dismissed, followed by Grace in quick succession, but Lyttelton took the score past 60 and seemingly England were almost home.

Then Spofforth & Boyle bowled maiden over after maiden over, 16 in succession and the pressure mounted on England before Spofforth broke Lyttelton’s resistance, quickly followed by Steel and Reed, both for 0. Seven wickets down, 15 runs still needed. Five more runs were added before Lucas played on the England’s tail was exposed. 75-8, soon it was 75 for 9 when Boyle’s googlie hit Barnes on the glove and was caught by the Aussie Captain Murdock.

Peate took guard as the tension all around the ground was running high. He hit his first ball dangerously to leg and they ran for 2. Boyle almost bowled him with his next ball and did so with his third. Poor Studd at the other end never faced a ball and England had lost by 7 runs.

The crowd carried Spofforth, shoulder high into the pavillion. His match winning figures of 10 wickets for 90 runs were not to be bettered by an Australian until Bob Massie 90 years later. His last 11 overs he took 4 wickets for only 2 runs, an astonishing performance. Afterwards the full drama of the last half-hour of play was revealed. One spectator had dropped dead, one man had gnawed pieces out of the handle of his umbrella, one Englishman’s lips were ashen grey and his throat was so parched that he could hardly speak when he arrived at the wicket and the scorer’s hand trembled so much that he wrote Peate’s name as “geese” on the scoresheet.

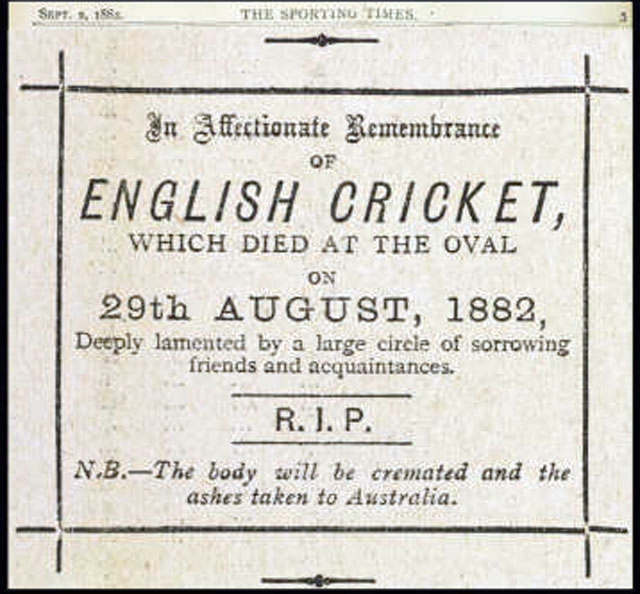

The Ashes concept came into being when Reginald Brooks, a journalist with the newspaper, The Sporting Times, published a mock obituary: "In affectionate remembrance of English cricket which died at The Oval, 29th August, 1882. Deeply lamented by a large circle of sorrowing friends and acquaintances, RIP. NB The body will be cremated and the Ashes taken to Australia." The English media dubbed the next English tour to Australia in 1882-83 as “The Quest to Regain the Ashes”.

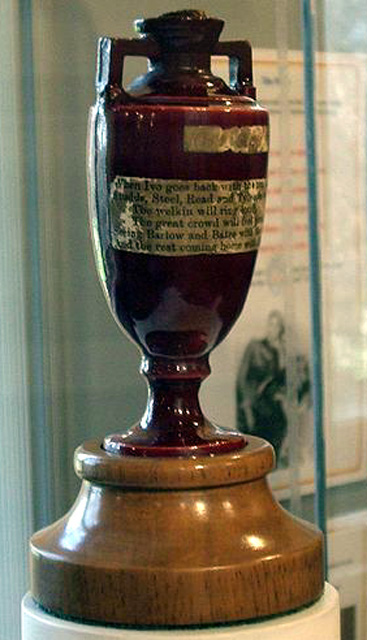

During that tour a small terracotta urn was presented to England Captain Ivo Bligh by a group of Melbourne women. The contents of the urn are reputed to be the ashes of a bail. Some Aborigines however believe that the ashes are those of King Cole, a cricketer who toured England in 1868. The Dowager Countess of Darnley claimed recently that her mother-in-law, Bligh’s wife Florence Morphy, said that they were the remains of a lady’s veil.

The urn is believed to be the trophy of the ashes series, but until Sky took over the viewing rights it has never been formally adopted as such and Bligh always considered it to be a personal gift. Nowadays a replica of the urn are held aloft by the victorious team and a Waterford Crystal representation of the ashes urn has been presented to the winners of an Ashes series as the official trophy of that series. The original urn normally remains in the Maylebone Cricket Club Museum At Lord’s since being presented to the MCC by Bligh’s widow upon his death.

by Roger Booth with inspiration from “The Cricketing Squire” by William Henry Hoole

England v Australia

Kennington Oval 28th & 29 August 1882 (3-day match)

Australia won the toss and decided to bat

Umpires: L Greenwood, R A Thorns

• * denotes captain

• + denotes wicketkeeper

Australia – 1st Innings

AC Bannerman |

c Grace b Peate |

9 |

H H Massie |

b Ulyett |

1 |

*W L Murdoch |

b Peate |

13 |

G J Bonnor |

b Barlow |

1 |

T P Horan |

b Barlow |

3 |

G Giffen |

b Peate |

2 |

+ J M Blackham |

c Grace b Barlow |

17 |

T W Garrett |

c Read b Peate |

10 |

H F Boyle |

b Barlow |

2 |

S P Jones |

c Barnes b Barlow |

0 |

F R Spofforth |

not out |

4 |

Extras |

(1 bye) |

1 |

Total |

all out (80 overs) |

63 |

Fall of wickets

6-1 (Massie), 21-2 (Murdoch), 22-3 (Bonnor), 26-4 (Bannerman), 30-5 (Horan), 30-6 (Giffen), 48-7 (Garrett), 53-8 (Boyle), 59-9 (Blackham), 63-10 (Jones)

England bowling |

Overs |

Maidens |

Runs |

Wickets |

Peate |

38 |

24 |

31 |

4 |

Ulyett |

9 |

5 |

11 |

1 |

Barlow |

31 |

22 |

19 |

5 |

Steel |

2 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

_________________________________________________________

England 1st Innings

R G Barlow |

c Bannerman b Spofforth |

11 |

W G Grace |

b Spofforth |

4 |

G Ulyett |

st Blackham b Spofforth |

26 |

A P Lucas |

c Blackham b Boyle |

9 |

+ A Lyttelton |

c Blackham b Spofforth |

2 |

CT Studd |

b Spofforth |

0 |

J M Read |

not out |

19 |

W Barnes |

b Boyle |

5 |

A G Steel |

b Garrett |

14 |

*A N Hornby |

b Spofforth |

2 |

E Peate |

c Boyle b Spofforth |

0 |

Extras |

(6 byes, 2 leg byes, 1 no ball) |

9 |

Total |

all out (71.3 overs) |

101 |

Fall of wickets

13-1 (Grace), 18-2 (Barlow), 57-3 (Ulyett), 59-4 (Lucas), 60-5 (Studd), 63-6 (Lyttelton), 70-7 (Barnes), 96-8 (Steel), 101-9 (Hornby), 101-10 (Peate)

Australia bowling |

Overs |

Maidens |

Runs |

Wickets |

Spofforth |

36.3 |

18 |

46 |

7 |

Garrett |

16 |

7 |

22 |

1 |

Boyle |

19 |

7 |

24 |

2 |

__________________________________________________________

Australia 2nd Innings

A C Bannerman |

c Studd b Barnes |

13 |

H H Massie |

b Steel |

55 |

G J Bonnor |

b Ulyett |

2 |

*W L Murdoch |

run out |

29 |

T P Horan |

c Grace b Peate |

2 |

G Giffen |

c Grace b Peate |

0 |

+J M Blackham |

c Lyttelton b Peate |

7 |

S P Jones |

run out |

6 |

F R Spofforth |

b Peate |

0 |

T W Garrett |

not out |

2 |

H F Boyle |

b Steel |

0 |

Extras |

(6 byes) |

6 |

Total |

all out (63 overs) |

122 |

Fall of wickets

66-1 (Massie), 70-2 (Bonnor), 70-3 (Bannerman), 79-4 (Horan), 79-5 (Giffen), 99-6 (Blackham), 114-7 (Jones), 117-8 (Spofforth), 122-9 (Murdoch), 122-10 (Boyle)

England bowling |

Overs |

Maidens |

Runs |

Wickets |

Barlow |

13 |

5 |

27 |

0 |

Ulyett |

6 |

2 |

10 |

1 |

Peate |

21 |

9 |

40 |

4 |

Studd |

4 |

1 |

9 |

0 |

Barnes |

12 |

5 |

15 |

1 |

Steel |

7 |

0 |

15 |

2 |

England 2nd Innings

W G Grace |

c Bannerman b Boyle |

32 |

*A N Hornby |

b Spofforth |

9 |

R G Barlow |

b Spofforth |

0 |

G Ulyett |

c Blackham b Spofforth |

11 |

A P Lucas |

b Spofforth |

5 |

+A Lyttelton |

b Spofforth |

12 |

A G Steel |

c & b Spofforth |

0 |

J M Read |

b Spofforth |

0 |

W Barnes |

c Murdoch b Boyle |

2 |

C T Studd |

not out |

0 |

E Peate |

b Boyle |

2 |

Extras |

(3 byes, 1 no ball) |

4 |

Total |

all out (55 overs) |

77 |

Fall of wickets

15-1 (Hornby), 15-2 (Barlow), 51-3 (Ulyett), 53-4 (Grace), 66-5 (Lyttelton), 70-6 (Steel), 70-7 (Read), 75-8 (Lucas), 75-9 (Barnes), 77-10 (Peate)

Australia Bowling |

Overs |

Maidens |

Runs |

Wickets |

Spofforth |

28 |

15 |

44 |

7 |

Garrett |

7 |

2 |

10 |

0 |

Boyle |

20 |

11 |

19 |

3 |

Australia win by 7 runs