The Tour De France and the glamorous hi-tech world of modern cycle sport might seem far removed from the clog and shawl era of East Lancashire, but in 1896 Britain’s Arthur Linton won the Bordeaux-Paris race in record time, and his trainer was “Choppy” Warburton, one-time landlord of the Fisher’s Arms in Blackburn’s Birley Street.

“Choppy,” born James E. in Haslingden in 1842, came to Blackburn in 1877. He was already an accomplished runner with some remarkable victories under his belt. He trained on Cob Wall cricket ground and in the disused weaving shed of Daisy Street Mill, an early version of an all weather track.

Distance was no object to “Choppy:” he was comfortable racing two miles or twenty. He broke records and the pride of many of the country’s professional runners. It is said he once ran for 24 hours without stopping. Choppy went to America and had some notable victories there, becoming a great favourite with American race fans. When his running days were over, “Choppy” took to training cyclists and became well-known in France.

His nick-name came from his sea-going father, who, when asked how the weather had been on his recent voyage, invariably replied: “choppy.” “Choppy” died in Wood Green, London on the 17th of December 1897. His success on the track had not made him any money; the only money found in his house after his death was three half-pence.

By Norman Bury

An example of a Penny Farthing bicycle, the kind of cycle that John William Bury

was riding when he won a gold watch as first prize in a bike race.

Riding a bicycle in those far off days as a pastime is very hard to imagine, especially as those who rode them would have had little time to enjoy this as a pastime because of working long hour days, especially when daylight hours during winter were so short and the nights were very long. More likely it would possibly be used as a form of transport by those whose homes were a long distance away from their place of employment. Obviously, riding would be more of a summer time pursuit.

A medallion won by John William Bury on the 19th August 1890 for

winning a bicycle race on a penny farthing. It is engraved 'First Prize J.W. Bury'.

It seems almost impossible to even contemplate any one having energy left to ride home again after a tiring day’s work in the cotton weaving mill, that being six days a week as well. What manner of person could we expect to find with such exceptional capacity, who would not only ride one of these machines, but actually take part in a race as well? When you consider that the roads in those days would not be as smooth as they are today, how could anyone even think of anything other than resting up to get themselves off to work the following morning?

We do know however that the bicycle was undergoing some elementary changes since its first self propelled cousin appeared round about the second half of the 17th century. Various precursors to this machine were called ‘velocipedes’, from a French name dating back to the late 18th century.

A shield shaped medallion, part of the first prize of a gold watch won by

John William Bury in a bicycle race where he rode a penny farthing. It is engraved 'J.W.B'.

In England, early models were called hobby horses and later design changes also went through various title changes, too numerous to mention. One such which became popular in France about 1855 was constructed with a wooden frame and wooden wheels and iron tyres, with the pedals attached to the hub of the front or driver wheel, which was slightly higher than the rear wheel. This machine was known in England as the bone shaker, because of the effect on a rider pedaling over a rough road or a cobble stoned street.

A gold watch won by John William Bury as First Prize for a bicycle race in 1890.

In 1869 solid rubber tyres mounted on steel rims were introduced on a new machine in England which was the first to be patented under the name bicycle. James Starley, an English inventor produced the first machine incorporating most of the features of the so-called ordinary, or high wheel bicycle. The front wheel of Starley’s machine was as much as three times larger in diameter as the rear wheel, and so the high wheel, or “penny farthing” bicycle was born, named after currency of the day.

The reverse side of a medallion (part of a gold watch) won as first prize by

John William Bury for a bicycle race in which he rode a penny farthing.

Modifications and improvements over the next 15 years included the ball bearing and the pneumatic tyre. These inventions along with the use of weldless steel tubing and spring seats brought the bicycle to its highest point of development. However, the excessive vibration and instability of the high wheel bicycle caused inventors to turn their attention to reducing its height. About 1880, the so called safety, or low machine was developed. The wheels were of nearly equal size and the pedals attached to a sprocket through gears and a chain drove the wheel. A forerunner of today’s machine?

It was on a high wheel, or ‘penny farthing’ that my grandfather, John William Bury, won a bicycle race at the age of 19, receiving First Prize, a beautiful gold pocket watch, complete with two medallions and rather heavy gold chain, having all manner of attachments, including a winding key. Designed to be worn with a waistcoat, the height of fashion in that period, it has two pocket ‘anchor pin’ T bars to secure the lengthy gold chain to button holes, producing that wonderful pendulous appearance, so typical of the era.

A photograph of John William Bury, the grandfather of Norman Bury from Melbourne, Australia.

Both faces of these very ornate gold medallions are inscribed as follows:

On the first shield face is a second and smaller shield with the initials inscribed: ‘J W B’

On the plain reverse side is inscribed:

‘Won by J. W. Bury, August 19, 1890’

On the second shield shaped medallion it has: ‘First Prize, J. W. Bury’.

On the reverse is a shield with an engraving of a ‘penny farthing’ bicycle.

The gold watch itself is still in first class condition, and working perfectly. No doubt attributed to the fine workmanship of the manufacturers, Waltham U.S.A., whose name it carries on the white dial.

A medallion engraved with a picture of a Penny Farthing bicycle (part of a gold watch)

won as first prize by John William Bury for a bicycle race in which he rode a penny farthing.

Where this historic race took place, I cannot begin to speculate, other than to say that one or two possibilities come to mind. Family records seem to indicate that he was living at 17 Dean Street Darwen at the time, so maybe Darwen Fair, mentioned in a letter, or a local Gala, Tockholes perhaps, but wherever it was, it must have been very hard work, having seen for myself the very hilly terrain around the Darwen area.

The Ribble Valley beckons

There are those hardy souls who cycle all year round, in all kinds of weather, but for those who prefer a softer edge to the wind and the chance of a bit of sunshine, now's the time to get the bike out of the shed, oil the chain, test the breaks and head for the open road.

The advent of the bicycle had a big impact on the lives of ordinary people - personal mobility was suddenly feasible. Formerly, in their brief leisure time, a walk up Preston New Road was about all shop and mill workers had time for, now the countryside was within reach, the seaside for determined pedallers.

Blackburn Bicycle Club was formed at a meeting in the Market Tavern in June 1880. This was in the days of the 'penny-farthing,' when cycling was the preserve of the well-off. The Blackburn club's outings were on Monday and Thursday evenings, Wednesday mornings and Saturdays, times when most folk were still at work. The club had a uniform of chocolate-coloured Norfolk jacket, knee breeches, stockings and blue caps. Illustrator and artist Herbert Railton was a founder member.

It wasn't until the 1890s when the 'safety' appeared that bicycles became more affordable and the world began to open up for ordinary men and women. Thomas Johnson of Blackburn published an early 'Cyclist's Road Book and Guide,' with over 100 routes, many of them to surrounding towns and beauty spots, but one detailing the route to Scarborough - a fearsome 118 miles.

Daniel Thwaites declining the honour of vice-presidency of the Blackburn Cycling Club on the grounds that bikes are a public danger.

Blackburn Eagles Cycling Club

Memories of Blackburn Eagles Cycling and Social Club

by

former member Ken Hartley

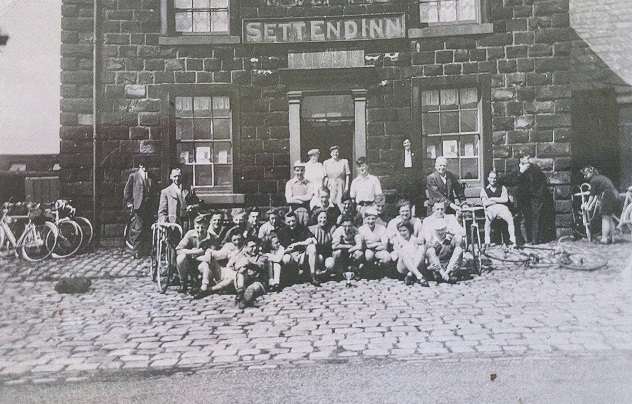

Blackburn Eagles Cycling Club outside the Sett End Inn,

Shadsworth Road in Early 1950's

I recall the ‘social’ was dropped from the Club’s name fairly early on. I have stirred the ashes of my memory of the late 1940’s and have retrieved the relevant bits of my memories. With the encouragement of our schoolteacher, social historian and novelist Miss Jessica Lofthouse. I, along with two school pals explored the Ribblehead area on solid steel bikes, mine was a B.S.A.

Miss Lofthouse had already whetted our appetite for castles and potholes. Our end of term on train trips from Daisyfield station to Hellifield, would be followed by at least 15 miles of walking in the limestone areas close to Settle and along the nearby Attermire Crags.

After leaving Bangor Street School to start our apprenticeships, we regularly pedalled our heavy steel monsters, and with the assistance of the excellent Bartholomew’s cyclist map we visited numerous potholes: Gaping Ghyll, Hunt Pot and Hull Pot. One day en-route home from the Dales via Sawley we were overtaken by a group from Blackburn Cyclist’s Touring Club who made it clear they didn’t want 14 year olds slowing them down. Hence the news of an alternative club which seemed to draw members of all ages mostly from the Intack/Audley/Queen’s Park areas of Blackburn caught our attention and we quickly joined the Blackburn Eagles Cycling Club and were soon enjoying Club cycling with as many as sixty riders on their weekly Sunday Club runs.

The club met in the function room over the Co-op opposite Queen’s Park gates every Thursday evening. The Club night involved discussion on the next ride’s destination and a report from the leader of the previous Sunday’s ride: great training for public speaking. The four very senior officers had all been pre-war Clubmen, of those only Charlie Tattersall was still riding. Ted Blackwell, a prominent butcher, and Bill Ward were no longer active but were very much involved in the races the Club ran.

Membership, like everything else in the 1940’s was in a state of flux, with lads returning from active service and others leaving on ‘conscription’ then later ‘National Service’. The National Cycling body: the ‘Road Time Trial Council’ had long had a hard and fast rule on race clothing ‘black from wrist to ankle’ and with clothing on ration racing cyclists used anything going. The first racing vest I ever saw was worn by Mr. Ward’s son Bill Ward Jnr. It had been knitted in black wool by his sister and fit him ‘were it touched’. It had a wide blue chest band between two narrower yellow bands. Where she got the wool was a mystery, but her design was to be adopted as the Club colours.

The club ran three Club races: two with a distance of 25 miles on the A59 at Copster Green and one of 5 miles massed start which involved four laps on the roads by Queen’s Park Hospital (Bank Hey Lane, Shadsworth Road and Haslingden Road). The short hill near what was then the Nurses Home usually sorted out the result on the last lap with nurses hanging out of their windows shouting encouragement. The last half mile to the finish on Haslingden Road had the four ‘star riders’ watching each other and in doing so let a little unknown kid, Ken Hartley take the lead for his first win, many more were to follow. The prize presentation took place at the Sett End Inn (demolished in the early 1960’s, to be replaced by a later pub bearing the same name but on the opposite side of Shadsworth Road). This race win started what was to be a lifelong association with all things ‘velo’.

The Club’s 25 mile Time Trials were much too long and arduous for my under-developed legs though they regularly got me into the top ten. My later teen years saw me winning open 25 mile time trials from Carlisle to Sheffield, resulting in an invitation to ride in the prestigious ‘Solihull Invitation’, a scratch 25 mile time trial for the best 25 riders in the U.K. This prompted our club elders to give me 15 shillings for my train fare (all clandestine), as I could have lost my amateur status.

National Service decimated ‘The Eagles’, and though the then Secretary Jim Bullen tried hard to keep the club going The Eagles never really recovered and finally folded in 1956. By which time I had already left to join another racing club, the North Lancs Road Club. All my pals were ‘Road Club’ men and I felt pressured to join them, though to this day I often feel I let down Jim Bullen by leaving The Eagles.

In its heyday The Eagles were rivalled, in size at least by two other local cycling Clubs: Pleasington C&AC and Darwen Cycle Club, the latter was alleged to be the oldest or one of the oldest cycling clubs still active in the post-war years. Whilst the Sunday Club run was at the heart of the Club, many of its members raced under the National Clarion ‘colours’ who catered for the most competitive riding.

With cycling numbers rocketing in the 1950’s, Whalley car park on a Sunday evening regularly saw hundreds of bikes as club members queued at one of the three cafes before the ride home to Blackburn or Accrington. The village’s four pubs catering for the more senior members. The advent of Sunday evening cinema had an immediate effect on the late return home and actually resulted in the closure of Sunday ‘last meal’ cafes. ‘Run Lists’ destinations and meeting times were posted on ‘wall notices’ in Whalley and in bike shop windows and the ‘out and about’ column in all of the many East Lancashire newspapers i.e. The Evening Telegraph, Blackburn Times and Darwen Advertiser.

Published September 2023 with grateful thanks to Charles Jepson for supplying the information.