Christmas was not always celebrated as it is now. The issue of the Blackburn Mail, which was actually published on December 25th 1793, has no reference to Christmas whatsoever. Clearly then it was not a day for celebration and probably not a holiday for most people.

One hundred years later things were very different. Blackburn had become a town, no longer a large village. There was greater prosperity. Christmas had become a commercial opportunity. Queen Victoria had made Christmas trees fashionable. Charles Dickens had single-handedly invented many of the traditions we associate with Christmas. The Blackburn Standard for December 23rd 1893 is full of articles and stories about Christmas. Shop displays are described in great detail, especially the butchers and poulterers: Messrs Munroe and Miller of the Market House had a display of a thousand turkeys, Fylde-fed geese, hares, pheasants, partridges and grouse, along with seasonal fruit and flowers. The best display of all though was at Messrs Worswick Bros, the furriers in King William Street. They had got their window up as a forest scene and filled it with stuffed examples of best-selling lines: Tiger, leopard, Russian wolf, seal, otter etc.

The paper carried a stern editorial criticising a London-based lady journalist, who had written a world-weary piece complaining that Christmas had become too long, too overblown and that there was nothing to do, but eat and drink too much in the company of relatives one couldn't stand. Wonder what she'd think of today's Christmases.

In Darwen too Christmas had blossomed and Darwen's shops too did not lag behind in displaying their abundance. The accompanying piece from the Darwen News for December 22nd 1888 captures the spirit of the season.

Fifty years later the Northern Daily Telegraph for December 24th 1943 reflects the sombre war-time mood. Christmas is featured, but it is clearly going to be a low-key affair. There will be no oranges, apples or nuts in Christmas stockings. Chickens and turkeys are in short supply, and an item about a woman making new clothes out of her husband's old suit to give to her children at Christmas is reported with great approval.

Today Christmas is more bloated and demanding than ever before. The carols are echoing round the shopping centres from November onwards, and when most people can eat and drink more than is good for them every day of the year, doing justice to Christmas requires a real effort. Most homes with children in them look like Santa's grotto on Christmas morning. It makes you wonder: had Scrooge got it right in the first place, before the ghosts started meddling with him?

The following photos were taken a few years ago showing a heavy fall of snow, giving Corporation Park a very "Christmassy" look.

This charming postcard brings to mind the popular song of the 1900s “After The Ball Was Over” which tells the sad story of a man and his bride-to-be. On returning from getting her a drink of water he finds her kissing another man. He refuses to hear her explanation and calls the wedding off. Only after she dies of a broken heart does he discover that the “other man” was her brother.

Higher Hill, Tockholes

The year is 1930 and we see Tockholes disappearing under a deluge of snow. How unlike the winters of today! But Tockholes suffered a similar experience 50 years later in 1981 when the village was cut off for over a week and the drifts were more than 10 feet high. The name of the village is derived from Tocca who dwelt in a hollow or clough “Tocca’s Hollow” becoming Tockholes.

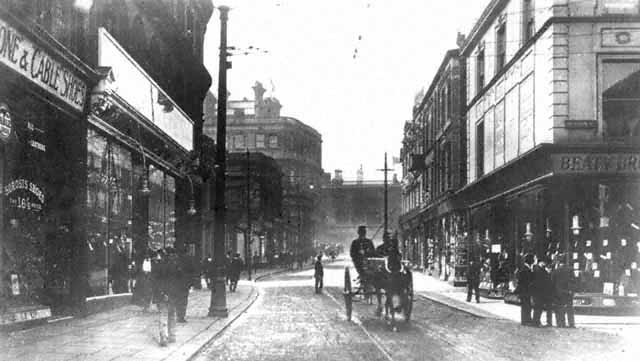

A once familiar view of Preston New Road with the tram and the horse drawn cart adding a touch of “old world charm”. Sadly the elegant shops on the right were demolished for the inner relief road known as “ Barbara Castle Way”. The church at the left is St. George’s Presbyterian Church.

The gabled building in the background was the birthplace of Professor John Garstang, famous archaeologist.

This view is taken from Brungerley Bridge. In 1801 a wooden bridge was erected by public subscription, with Clitheroe Corporation contributing 3 guineas (£3.30 pence) towards the cost. Prior to that, no bridge had existed. By 1816 it had fallen into such a state of decay that it was unfit for use. It was replaced by the present stone bridge, also paid for by public subscription. This time the Corporation contributed £60.

Corporation Park in Winter

The Preston New Road entrance in the 1950s. Originally this snow covered flower container was the largest of the Park’s 4 fountains. It caused annoyance to park users with the drift from the water jet and it was eventually turned off and the basin was filled with flowers.

Darwen in Snow

This view of Darwen is taken from the Pickup Bank area. On the skyline Darwen Tower is just visible. The Tower was built to commemorate Queen Victoria’s Diamond Jubilee in 1898. The surrounding hills look particularly bleak and foreboding in this shot.

The Boulevard

A 1950s image of the Boulevard. Usually a busy area, this shot seems to be almost devoid of people. Perhaps the townsfolk had hurried home to avoid the worst of the weather. The large building in the background is the Palace Theatre which opened in 1899. It was once a thriving music hall, which became a cinema and ended its days as a bingo hall. It was demolished in 1988.

A Look Around The Shops

And A Peep At Other Institutions,

[“Standard And Express” Special]

Transcribed form the Blackburn Standard & Weekly Express of 21st December 1901

Christmas might very properly be regarded as our greatest institution, and however elaborate are the preparations for its recognition, they are never greater than the festive season merits. The Christmas of our childhood is always associated with a hoary frost and a snow-bound earth, and we are unable to conceive of one without the other. Now we have come to realise that our ideas were as immature as our experience, and we regard the “green Christmas” as something to be looked for. We have had so many of them in recent years and the snowy herald of the joyful season is a thing almost lost to memory dear. But this year has so far, proved an exception to the rule, and I feel sure we are all thankful. Christmas without snow is like Hamlet without the Prince of Denmark, and one puts more zest in his festivities at this time if the snow is several feet in thickness and hoar frost glitters in the moonlight like diamonds in a claim.

There are few tradesmen who don’t devote a good deal of extra time and labour to the improvement of their customary show, and my experience has been that there are few of these displays that don’t well repay a few minutes observation. I trotted round the principal streets of the town the other evening and glanced at a few of the shop windows. They were all decked in Christmas finery and they all repaid those who were responsible for the adornment.

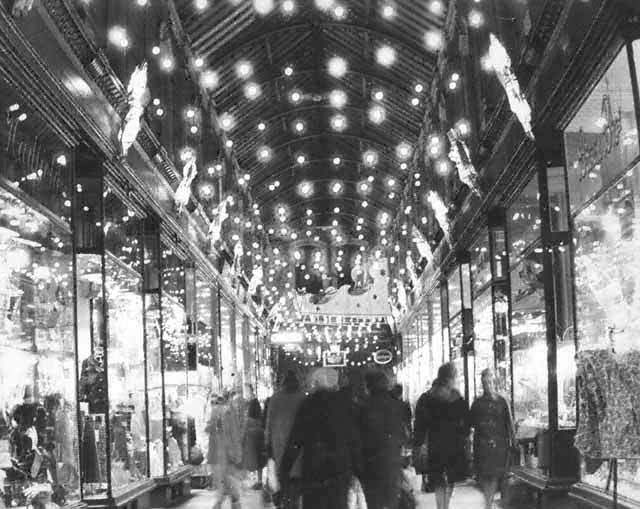

Church-street made a good display. “Astley’s” newsagency was one mass of seasonable missives of every kind. They were there in thousands, large and small, cheap and costly, but all assisting to produce an effect only attainable by a combination of deft fingers and excellent materials. Higher up the street Mr. Crossley’s well-known novelty emporium was looking even better than usual. A miniature electric train made a circuitous tour of the window front, passing a host of charming Christmas presents and encircling an assortment of both useful and beautiful articles fashioned in almost every conceivable design, and calculated to please the most fastidious. Mr. Sagar, jeweller, exhibited a collection of jewellery attractive and valuable, a new stock making a small window swell almost with its own importance. I walked on and saw that excellent provision was made by “Tills,” tailors and as I shivered with the cold I envied this enterprising firm their splendid stock of winter coatings and suitings, and marvelled at the ingenuity which had made up-to-date fashion and splendid value shine with such lustre in the public eye. I found a similar state of things at “Leavers,” who made a brave show and also at Dewhurst’s. At the shop of “Harris and Sons,” in Northgate, I stopped to admire the fine collection of ladies’ silks, umbrellas, etc. I then traversed King William-street with admiration. The window of “Worswick Bros,” the furriers, was a treat as it usually is and the spectator wondered as he gazed on the scene whether a herd of valuable skinned animals had suddenly stopped short in a tramp among the scores of costly garments, which, by the way are among the most adaptable winter wearing apparel I have seen.

“King and Blackburn’s” made a grand show, and went in for colour with magnificent effect. Their window was a treat, and one surveyed bargains of all kinds peeping from beneath their season’s coating of floral or decoration. At the shop of “Mellor Bros.” was a seasonable variety of gentlemen’s necessaries, all with tempting appearances and calculated to inspire the average young “Johnny” with envy. Round the corner the Shop window of Mr Whittle, Jeweller, possessed a grandeur all its own. The stock of rings was a splendid one, and the prices such as could not possibly prove a matrimonial barrier. His show of watches was just as good, but one of them silently reminded me that there were other displays to view, and I peered inside the Market Hall and gazed on the long rows of pheasants at Munroe and Miller’s stall, with a sigh for the families of the birds and an admiration for the shots who had “potted” them. I looked in on the special show of novelties at the establishment owned by Simpson and Son’s. Ltd., Market-place, and fancied myself a millionaire for a few minutes as I wended my way in and out of long rows of statuettes, pottery, art goods, fancy chairs and Japanese screens. I also dropped in to see the grand display of furniture, carpets, etc., at the shop of Thos. and Sidney Smith, in Ainsworth-street, where a window decked out to represent an up-to-date furnished bedroom charmingly arranged, was attracting a good deal of attention. I also traversed the lower end of Preston New-road, where Mr. Wyatt’s splendid “at home” work was attracting a great deal of attention.

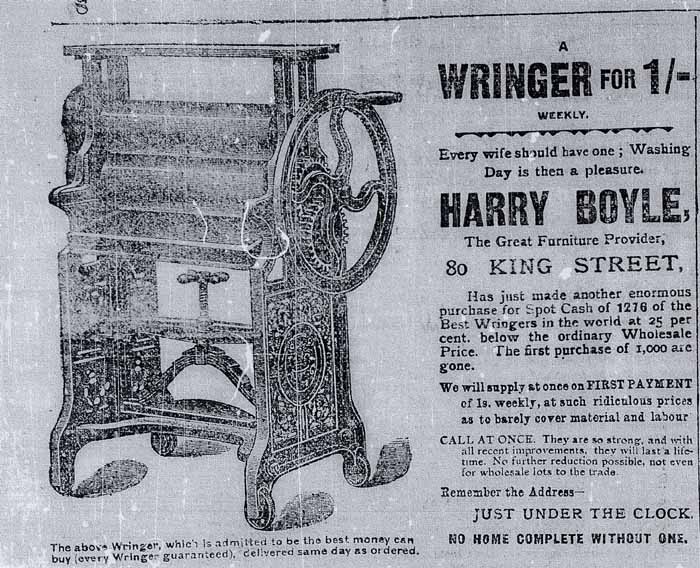

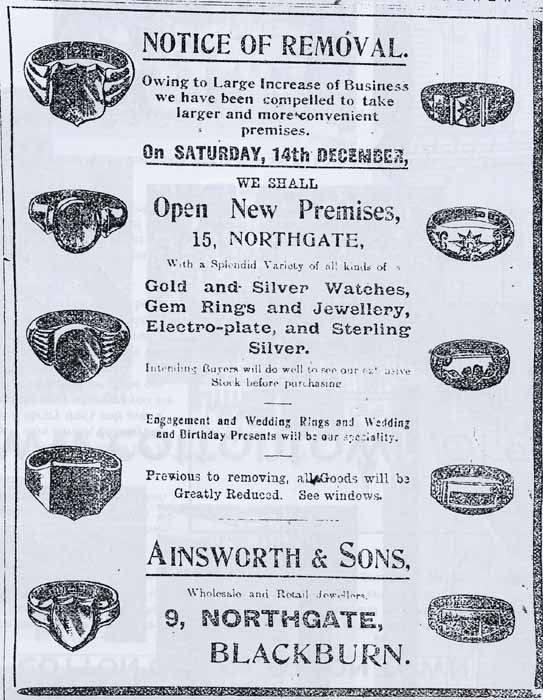

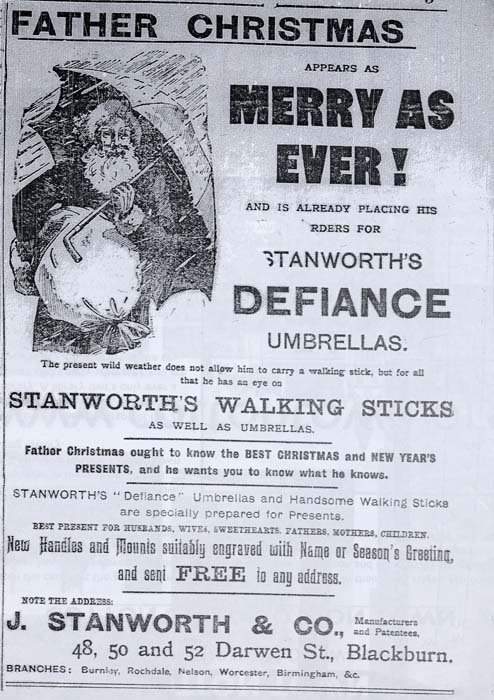

Mr Garsden’s grand display of beef, mutton, etc., in Northgate, made me wish for Christmas before its time. Quality was written on every joint in language that need no notices to explain it. Retracing my steps, Gibson’s in King William-street attracted my attention with the customary tempting and admirably laid-out selection of seasonable fruits. In Darwen-street “Stanworth’s” showed a magnificent stock of umbrellas and walking-sticks, arranged in their well-known admirable style, whilst the Castle Wine Stores in Market –street Lane, Mr. Blakey came to the front as usual in the public estimation with his liquids. Booth and Openshaw’s window was a centre of attraction. Beautifully-chased scent bottles with dainty brightly-coloured tassels exhibited excellent taste and skill, and I was informed that Sandow’s developer was being advanced by this enterprising firm as a Christmas gift. In the musical line the show was not a brilliant one, but Mr. Edward Smith and Mr. Sharples are too well known to require any laudatory notice in these columns. The latter is just now making a speciality of a free lesson arrangement with purchasers to commemorate the festive season. I saw a lovely assortment of books, writing cases, dressing cases, ladies companions, and the like in the window of Denham’s, and the show of cards and stationery was one of the finest yet seen in the town. I also noticed that Page’s were offering some wonderful bargains in the way of ladies’ and children’s clothing at their shop in Eanam, and I did not forget to glance at and admire the beautiful selection of Jewellery in the newly-opened establishment of “Ainsworth and Sons” in Northgate. Special tea in specially decorated canisters was, I noticed, being sold by Thos. Jones and Co., Ltd., in Lord–street, and the assured me there was nothing so acceptable. On Victoria-street Green and Sons were endeavouring, with a fine show of fine-fed pork, tongue, sausages, etc., to enhance an enviable reputation for quality and cheapness, There was the usual crowd congregated round the window of Aireys, picture framers and art dealers in Railway-road, but my trouble to get a view was repaid by a glance at the choice water-colour drawings, etc., on view, and I had no difficulty in voting this one of the “treats.” The establishment of Mr. Sharples, in Darwen-street, was on the usual scale, filled with bargains and Christmas presents in every class of goods that are dealt with by an up-to-date silk mercer. Thompson Bros., tailors, Market-place, were well to the fore with their fine selection of winter clothing, and the Household Stores in Preston New-road made housekeepers rejoice to know that such excellent provision was made for Christmas appetites. Many more fine displays did I witness and “Fieldings,” jewellers, in Montague-street was one of the best with a well stocked window full of rings, brooches, watches, etc., admirably suited for Christmas presents, and arranged in a manner that could not fail to catch the eye. Much disappointment has been occasioned by the absence of Harry Boyle’s usual show. This is owing to police vigilance. Mr Boyle finds it necessary to utilise a little space in front of his shop, and the police authorities object. Green’s, in Penny-street, and Scholes, in Queen’s Park-road, always have displays as interesting as they are attractive, but Christmas usually witnesses an improvement. Their Christmas shows this year are fine, well worth seeing, and the bargains are such as only large dealers are accustomed to offer

The local supply of holly and mistletoe is not so great this year as in the past years, and dealers have been greatly inconvenienced owing to bad weather interfering with its transit. The first large consignment arrived on Thursday morning from Kent, where a large amount of the mistletoe is usually packed of to the north at Christmas time. Loads of holly continued to arrive during the day from Cheshire and Shropshire. The demand was pretty large on that and the following day, and it is calculated that upwards of twenty tons were distributed in Blackburn homes.

The scores whose needs are always greater than their supplies are not to be forgotten. At the Bent-street Ragged School, on Christmas morning four hundred poor children will be treated to breakfast, and 120 parcels, each containing articles of food, will be sent out to persons in need of assistance. In the afternoon four hundred poor people from the lodging-houses of the town will be entertained to tea, followed by an entertainment, and 130 cripples will receive at home a parcel each containing one shilling and articles of clothing.

There will be the customary treat provided for the inmates of the Workhouse on Christmas Day, and in order to do this handsomely 2,000lbs. of beef, mutton, etc., along with 1,000lbs. of plum pudding, as well as vegetables, will be cooked for consumption on the day. Fruit, tobacco, sweets, snuff, etc., will also be provided. A number of Guardians have, with several ladies and gentlemen of the town, contributed towards defraying the cost of the treat. The wards will be decorated and there will be the usual concert on the evening of Christmas Day. Similar provisions will be made at the Cottage Homes, where the children will spend the festive season just in the same way as other children. They will enjoy their games after a good dinner, and will then be allowed to visit their respective schools and witness or take part in the entertainments.

The usual admirable preparations have been made at the Post Office where there is always a prodigious amount of work to be got through during the festive season. About fifty extra men have been engaged for the delivery of letters and parcels on Christmas Eve and the following day, and Messrs. Hamer’s and Messrs. Smith’s auction rooms have been hired for the transaction of special parcel business and the housing of the extra postmen. In the Absence of delay it is expected that all the letters will be delivered by three o’clock on the afternoon of Christmas Day. The postal authorities in Blackburn inform us that they generally dealt with about 5,000 parcels at Christmas time, and it is expected that more will be dealt with this year. Several horses and conveyances have also been engaged for the carting of parcels.

Even now, when Christmas is so lavish and we want for nothing, I still remember with affection the excitement of Christmases as a young child when there was a scarcity of just about everything. The anticipation, weeks before the event, was intense and I never remember being disappointed on the day.

My first memory of Christmas was 1946 when I was three years old. There were six of us children then, dad was in the army and things must have been extremely difficult with necessities being in short supply and luxuries unheard of. Nevertheless our parents always managed to make something of the occasion for us. My very early memories of are of warmth and pleasure. I remember a big fire in the grate and all of us children sitting around the kitchen table with mum making chains out of coloured paper to be used for decorations, or trimmings as we called them. We spent ages cutting out the strips and forming them into circles using little pots of white, pasty glue. They were then made into long chains which would go from one corner of the room to the other. We had coloured balloons too which I remember trying to blow up but never having the breath - only Robert, the oldest of us, seemed able to get any air into them. We always had a little Christmas tree modestly decorated with bits and pieces of coloured crepe paper or fabric strips and baubles that had been collected by mum over the years. There were no lights on the tree of course but that tree, with its home made ribbons and garlands, was a glorious and amazing sight.

Festive Food

Food was then, as it is today, an important part of Christmas. There was always a Christmas pudding and preparation of the pudding was the first indication that the festive season was just around the corner. Mum always referred to the day when the pudding was made as ‘stir up Sunday’ My sister, Kathleen and I helped with stoning and washing the fruit and shredding the creamy coloured suet which was used well before suet came in packets. Before the pudding was ready, each one of us would get to stir the mixture whilst making a wish, mum would then add a couple of silver threepenny bits before putting it into the basin and steaming it for several hours.

I don’t remember much in the way of meat although I know we never had turkey, that didn’t come for many years. I doubt if we children bothered so much about the dinner part of the meal, which I suspect would have been made up mostly of vegetables and tolerated as part of filling yourself up when food was scare. It was always the ‘afters’ we relished. We loved the trifles mum made and the jam tarts, finished off with a blob of whipped Nestles cream, were scrumptious. A vivid memory I have is the time when mum took a freshly baked batch of tarts out of the oven and put them to cool. As she turned her back to do some job or other, dad surreptitiously popped a whole one into his mouth hoping he hadn’t been seen. Unfortunately the tarts were burning hot and the jam stuck to dad’s mouth, he was in agony but we kids thought it hilarious that he had been caught out, mum wasn’t too sympathetic either.

Christmas At School

Then, as now, Christmas activities at school were very important to us. We all attended Emmanuel C of E school at Ewood in the 1940s and in the run up to Christmas we loved the excitement of making cards to take home to our parents, practising for the nativity play and the carol service; every child in the school was involved in these activities. I remember one particular Christmas we went singing around the neighbourhood. We had all been asked to take a jam jar to school and the teacher lined the jars with red cellophane paper and a candle was put inside. The jar was then suspended by string from a stick. All the children from the school walked through the streets with the candles shining through the red of the cellophane. We sang carols as we walked along and stopped from time to time to allow the people from nearby houses to join in with the singing. I still remember how wonderful it was to see those glowing candles and hear all the voices singing in the cold night air.

Presents And Playthings

Of course, in the 1940s, people in our circumstances didn’t give parties and outside school we rarely went to any, in any case we had enough entertainment with the family to keep ourselves well amused. We sang, told stories and played card games such as Old Maid, Happy Families and Find the Lady. There were loads of parlour games too; charades, hide the thimble and blind man's bluff amongst others.

Although we didn’t get lots of present, a kind of tradition we had was choosing a book for ourselves. Although we often chose annuals such as The Dandy and The Beano, my favourite choice ever was ‘The Wizard of Oz’ – I still watch the film every Christmas and am always thoroughly enchanted with the story. The tradition was kept going for many years when choices changed to Boys Own Annual, The Eagle, The Girl and Girls Crystal along with some of the classics such as Treasure Island and Jane Eyre.

With a family of our size we had few shop bought presents. However, we didn’t really go short as many of our toys were made by dad who was very gifted in carpentry. Over the years I remember him making a fort for the boys and dolls house for us girls. He also made many wooden puzzles and a shove ha’penny board. We all got a great deal of pleasure from these homemade toys and I have spotted many of the kind of things dad made at local Craft Fairs. I’m told they still sell well.

Christmas has arrived

After what seemed like forever to us children, Christmas Eve eventually came around. We could scarcely contain our excitement; I think it was the only night of the year when we asked to go to bed.

Each one of us took a sock up with us to hang over the end of the bed. I still remember longing to go to sleep but feeling far too excited and anxious to even close my eyes. ‘Will Father Christmas come?’ I would whisper to my sister who shared the bed with me. ‘Not if you don’t go to sleep he won’t’, she would whisper back crossly. I would ask and ask until in the end she got so annoyed she would threaten to tell Father Christmas not to fill my stocking; that usually had the desired effect and we all drifted off to sleep.

We always woke early on Christmas morning and our stockings had disappeared. They were never left full on our beds and we were left to worry if ‘he’ had been.

None of us were allowed downstairs until the fire had been lit and everything was ready for us. I think it must have been Robert, the eldest of us, who decided that each of us would sit on a stair, with the youngest at the bottom and the oldest, himself, at the top. This stopped us falling over each other to get downstairs and kept us very orderly. We kept this up every year until there were eleven of us children and every step was occupied by a child.

Our presents were all kept in neat individual piles and, to our relief; our Christmas stocking was on the top. It was lovely emptying the stockings. Each one contained an apple, a tangerine, a handful of nuts and a small coin; pennies for the younger children and a nice shiny sixpence for the older ones. Sometimes there would be a few sweets too which, because we still had coupons, were a real treat.

Christmas day was the only day of the year when we didn’t have to sit at the table for breakfast. We were allowed to have it at the same time as we opened our presents and this relaxation of the strict rule of eating at the table was much appreciated. However, when it came time for our Christmas dinner we couldn’t wait to sit down. Great ceremony was made of pulling our crackers and everyone, including mum and dad, had to wear their paper hat. It seems very strange today but in those years Christmas day was the only time we were allowed to talk at the table and we enjoyed the relaxed atmosphere.

After our meal we usually played games and there was always plenty of laughter and sometimes arguments over who should have won or who was thought to have cheated; however, these disagreements didn’t last long and we always finished up tired and content.

Today things are very different, we want for nothing now but I always tried to make Christmas as traditional as possible for our daughter when she was a child and for her family when she married. However, our grandchildren are now in their teens and though they still have their Christmas stockings, the presents and the dinner, they no longer want to do the same things as when they were children. And this is the way it should be, things move on. I do hope though that they will remember their young Christmases with as much affection as I remember mine.

By Marian Beck

back to top

History of the Christmas Tree

Although the history of the Christmas tree dates back nearly a 1000 years to Germany and St. Boniface, it was not until the early 17th century that the people there began taking them in to their homes and decorating them. At that time they would be decorated with barley sugar, wax ornaments, paper flowers and all sorts of little trinkets.

Queen Charlotte, the German wife of George III, is said to have introduced the Christmas Tree to this country for a party that was held at Windsor on Christmas Day. The young Victoria always had a decorated tree at her home in Kensington Palace.

In 1848 a woodcut illustration appeared in the Illustrated London News showing Queen Victoria with her husband Prince Albert and their children standing around their tree at Windsor. The Duchess of Kent (The Queen's mother) is also shown to the left of the queen. The tree was decorated with wax tapers. Hanging from the branches were coloured ribbons and tied to them were baskets of sweetmeats, gingerbread, eggs full of toffee and other sweet things. Under the tree were piles of presents each with the name of the recipient written on a label.

Victoria, at this time, was a very popular ruler, unlike her German predecessors, and when the above picture appeared Christmas trees began to gain in popularity. Most decorations would have been home made at this time and hours would be spent in making the decorations and hanging them on the tree.

As time went by the Christmas tree went through phases, by the 1890 large and highly elaborately decorated tree were the vogue. By this time commercial decorations could be bought but a lot were still home made. After the death of the Queen the large Christmas tree went somewhat into decline and people had small trees that would sit on a table. Some of these would have been artificial ones, which started to appear in the late 19th century.

After the hardships of World War Two, people once again started to buy the biggest trees they could afford and gaudy decorations began to appear such as plastic stars, icicles, paper angels, bells and glass balls. Flashing lights would be draped round the tree.

Now in the 21st century most trees seem to be artificial and can be very good imitations of the real thing, when decorated they can add warmth and joy to an otherwise cold, damp wet time of the year, and as long as they bring joy to the children I think that’s all that really matters.

The Christmas Pudding

The Christmas pudding can be traced back to the 14th century, but its beginnings are a far cry from what it is today. It was originally known as a porridge or frumenty and contained things like beef, mutton, raisins, currents, prunes, wines and spices it was at this time more like a soup or porridge and was eaten as a fasting dish before Christmas. By the 1500s other ingredients were being added to thicken up the dish, such as dried fruit, eggs, breadcrumbs. The meat at some time was removed from the dish and replaced by more fruit and sweeter ingredients. The puritans banned it in the 1660s. They thought it a vulgar tradition, the ingredients being, “far too rich for God fearing people”.

King George I was thought to have made the Christmas pudding part of the Christmas celebrations, but it was Prince Albert, Queen Victoria’s husband, who, having an insatiable appetite for the pudding made it a tradition.

It was traditionally made on the Sunday before Advent, which was 5 weeks before Christmas. The day was known as “stir up Sunday” from the opening lines of the collect for that day in the book of common prayer:

“Stir up, we beseech thee, O Lord, the wills of thy faithful people…”

The verse became associated with the Christmas pudding and the stirring of it. The pudding was made with 13 ingredients, which represented Christ and His Disciples and every member of the family would stir it with a wooden spoon making a wish whilst doing so. The stirring had to be from east to west in honour of the three Kings. At this stage silver three-penny bits, or rings were added into the mixture. It was then left until ready for cooking. The initial steaming of the pudding would take about 8 hours and then on Christmas day it would get a further steaming for 4 hours. A sprig of holly was added which signified the crown of thorns and just before taking it to the table, brandy was poured over it and set alight. This was said to represent Christ’s passion.

Each person would look through his or her portion of pudding in the hope of finding a charm; the money would mean wealth in the coming year and the ring foretold a marriage or romance.

Now-a-days most people neither have the time nor inclination to make their own Christmas puddings. It is much easier to go to the supermarket and “buy one, get one free”

What a lot we are missing out on.

The Christmas Card

The first commercially produced Christmas card, was commissioned by Sir Henry Cole and drawn by John Calcott Horsley in 1843. The card shows a moderately wealthy English family enjoying Christmas, and each side depicts people in the act of charity, which was a very important part of the Victorian Christmas. Not everyone thought the card appropriate and some religious groups condemned it. The temperance society condemned it for depicting a young child taking a sip of wine. Sir Henry Cole had a thousand copies of the card printed. Some of them were given to his friends and the remainder were sold for one shilling (5p) a card. The early cards rarely had religious or even winter themes, but would show children or animals. The following year W.C.D. Dobson produced another card for sale and in 1848 W.M Edgley produced a card which was similar to the one J.C. Horsley had done. The card had holly on it for the first time and used the spelling “Christmass”. With the penny post, introduced in 1840, Christmas card sales soared and became a success. When printing methods improved Christmas cards become big business and by 1878 over 4 million cards were sent. Charles Goodall and Son, was one of the first firms to mass publish Christmas cards. In 1866 C.H. Bennett designed a set of four cards for Josiah Goodall. They were printed in Ireland and became the forerunner of the Christmas card as we know it today. The cards now depicted the nativity but robins (the postmen at this time were called Robins because of their red uniforms), snow scenes, holly and other winter scenes were also used.

Today the Christmas card is big business and millions are sent each December all over the world. The designs on them have changed and now you can buy them with all sorts of pictures on them: traditional winter scene, comic or cartoon characters. Cards with jokes on them even vulgar ones are now on sale. The only sort which seems to have seen a down turn in their sales are the ones showing religious scenes which is a shame really, because that is what Christmas is supposed to be about.

The Christmas Carol

The word carol comes from the old French word carole meaning “round dance with singing”. It was originally associated with seasons of the year and not just Christmas. One of the earliest known songs to do with Christmas is ”Jesus refulsit omnium” which was composed by Hilary of Poitiersne in the 4th century. St. Francis of Assisi (1181-1226) introduced Christmas carols to the church service. He also used them in the nativity plays he made. During the 15th century in Italy carols were written with a more festive slant to them. In the same century Johannes Gutenberg made his printing press (about 1447). With this copies of carols could be easily made and distributed to other churches. The earliest English printed carols came from the press of Wynken de Worde (yes that was his name), which included the Boar's Head carol. When the puritans came to power in the 17th century, as with all other Christmas traditions, the Christmas carol was banned and many copies of older carols were destroyed.

It was the 18th and 19th century when most of the carols we know and love today were written. Every church now has a carol service at Christmas. Perhaps the most famous is 'The Festival of Nine Lessons and Carols' held in King's College Chapel, Cambridge. It takes place on Christmas Eve and always begins with the carol, 'Once in Royal David's City,' the first verse of which is sung by a solo chorister. The service ends with the carol “Hark! The Herald Angels Sing”. The service was first performed in 1918 and revised in 1919. It was started by the newly appointed Dean of Kings, Eric Milner-White. The service was first broadcast to the nation in 1928 and apart from 1930 has been broadcast annually. It was broadcast throughout World War Two.

History of Father Christmas

The history of Father Christmas goes back to the 3rd century A.D. to Saint Nicholas. He was born in Patara in modern day Turkey about 280 A.D. He is the patron saint of Russia and, among others, pawnbrokers, parish clerks, seamen and many others, but more famously, the patron saint of children. Nicholas was a very pious and kind man who, it is said, gave away his wealth to the poor and needy. One thing he was noted for was giving secret gifts to children. He would also go out in a hooded cloak and leave clothing, food and money for poor families. All his good deeds made him very popular especially with children, in fact he became known as protector of children. He died on the 6th of December, which became his feast day. By the 15th century Nicholas had become the most popular saint in Europe.

A Father Christmas type figure appeared in ancient British mid winter festivals, dressed in green robes with a wreath of holy and mistletoe on his head. In the 5th and 6th century he was known as King Frost. Someone would dress in a green robe and would visit people's houses. He would be given something to eat and drink. By being good to him, it was thought he would bring good luck to people.

When the Normans invaded in 1066 they brought the story of St. Nicholas with them, and, with this story added to the stories of the Saxons and Vikings, the idea of Father Christmas was born. He is mentioned in an old 15th century carol as Lord Christmas”.

The puritans banned Father Christmas, along with other Christmas traditions in the 17th century, but he was not forgotten and during that period of history he went underground, being remembered in mummers' plays and underground newspapers

By the mid Victorian period Father Christmas had more or less got all the characteristics he is now famous for. He is portrayed as a well fed, happy, bearded man, dressed in a green-fur lined robe and is depicted like this in Dickens book “A Christmas Carol” as the ghost of Christmas present. His outfit however was yet to be standardised. Pictures of that time show him dressed in a red, blue, green or brown costume, sometimes covered in stars. Thomas Nast, the American cartoonist, shows Santa Claus visiting an army camp during the American civil war and handing presents out. Another American, Clement C. Moore, wrote in 1822 the now famous poem “The Night before Christmas”.

Father Christmas was now being highly influenced by America and the final touch was made by Coca Cola, who in 1931 gave us the Santa we know today.

In recent years some school have tried to change Santa or even do away with him altogether. They have tried to change the colour of his costume into a green one, and have even told children that he does not exist. Even in our multicultural society there must be room for Father Christmas otherwise where will we all end up?

By the way I hope you have written your letters to Santa. There’s not much time left if you want that special gift.

Merry Christmas To you All!

By Stephen Smith

back to top

For this festive time of year we are featuring 3 seasonal poems by Helen Lee, taken from an anthology entitled "Bits of Things", published 1893; along with articles from the Blackburn Times on Christmas fare and Christmas weather.

The Christmas Dinner

It seems to be well nigh impossible to vary the Christmas dinner very much, and the majority are well content to sit down year after year to a turkey, goose or big joint of Christmas beef, with plum pudding, mince pies and Stilton cheese to follow. Some indulge instead in a roast sucking pig, a leg of pork or a hare, but somehow these scarcely seem so Christmas like as the turkey. Fowls, ducks and pheasants come in for small families where a turkey - even a small one is deemed too large and where warmed up foods are not liked. The day after it has been roasted the turkey is however quite delicious served cold. When it is re-heated it is important not to give it a harsh-like taste or to take away the piquant flavour of the bird itself by adding too many other ingredients. To re-heat gently in a delicately flavoured sauce is better, never letting this boil when once the meat has been added. Stewed celery, Brussels sprouts, parsnips, haricot beans are all suitable vegetables to serve on Christmas Day.

A seasoned pudding may be served with a roast leg of pork instead of stuffing, if liked. It is made with 1lb of crumbs of bread, a large boiled onion, a dessert-spoonful of dried sage, a little salt and pepper and one or two eggs.

A very simple stuffing for a turkey is preferred by some and is far more likely to agree. It can be made with 4oz. breadcrumbs, 2 oz. suet, a tablespoon of mixed herbs, seasoning to taste and an egg and a little milk.

For stuffing a goose, take 4 onions, boil till tender, mince them very finely with 7 or 8 well scalded and dried sage leaves and mix with 5 oz. freshly grated crumbs, 2 oz. chopped beef suet and a good seasoning of salt and black pepper. Bind with the yolk of an egg.

A good cold sauce for the plum-pudding is made by beating to a light white cream, equal quantities of fesh butter and brown sugar and flavouring with a squeeze of lemon and a dash of grated nutmeg. Set in a very cold place till wanted and send to table in a glass dish.

For the Christmas dinner of an invalid, a chicken may be placed in a large basin ina steamer over boiling water. Cover tightly with a lid, steam for 2 hours and serve with white sauce. This may often be eaten when the doctor will not allow roast birds.

It is not a bad plan when preparing the Christmas turkey to fill the crop with sausage meat and to make a veal forcemeat for the inside. Two or three slices of bacon can be skewered over the breast, but must be removed 20 minutes before serving.

The feet of a goose should be yellow, because as the bird gets older the feet take on a deeper hue. Only add just enough water to the apples for apple sauce for the goose to keep them from burning. When reduced to pulp, mix in a little sugar, a squeeze of lemon and a tiny bit of butter. Some people who object to the richness of an ordinary stuffing, fill a goose with sliced apples instead and then do not make apple sauce.

Never use indifferent fat for roasting a bird on Christmas Day, it can give the meat an objectionable flavour. Be quite sure beforehand that the dripping you are going to use is of the best. Don't cook the Christmas beef in a cool oven or it will be sodden.

A hare pie, with forcemeat and fresh sausage in it is very nice at Christmas time and hare soup is delicious. So if generous people shower more than one hare upon you, hang the one that will keep best and then serve it up quite differently from its predecessor.

Blackburn Times, 1913

The Christmas Weather

In olden times there were many simple and inexpensive means of foretelling the weather and people would as boldly predict for next years as for the ensuing afternoon. There were certain days in the year which were set apart as specially guiding them to the climatic conditions for weeks or months after, and rightly or wrongly, the belief in many of these days still holds good when a large number of people are gathered together.

Although we no longer look on Christmas Day as an infallible guide to the future, there are many persons who have a hazy notion of the day's influence on coming events. All Saints and Christmas Days were said to have the same weather, while according to the Sardinians, that of St. Lucy (December 13th) was just the reverse. As to Christmas and the days near the festival, they served to foretell the whole of the following year, and naturally the old saying-"A green Christmas makes a fat churchyard" was taken for granted.

According to various prognostications we find: When Christmas Day cometh while the moon waxeth, it shall be a very good year, and the nearer it cometh to the new moon the better shall that year be.

When on the Christmas night and evening it is very fair and clear weather, and it is without wind and rain, then it is a token that the year will be plentiful in wine and fruit. An abundant crop of apples was expected if on Christmas Day the sun came through the apple tree.

Blackburn Times 1918

By Stephen Smith

“Bonfire night, the stars are bright,

And all the little angels are dressed in white.”

That was a song for the girls, and for the little kids, not for the likes of us. You wouldn’t catch us singing songs like that, no way. At eight years old we were above songs like that, except at school when we were forced to, but the words stuck in our throats. We had to imagine a bonfire in the middle of the hall and skip round it singing those words, uhk! Perhaps if the teachers had let us sing the next few lines we would have been suited, but they never did.

Can you eat a biscuit?

Can you smoke a pipe?

Can you go a-courting

At ten o’clock at night?

Bonfire night came in its season like everything else in those days. There was a marble season, conker season, football and cricket seasons, and they all came round in their turn. There wasn’t a recognised time for these seasons to start, they just happened. One day you would see everybody playing marbles, or some other game and that would be the beginning of it and just as suddenly, it would be over. Bonfire night was like that, one day, about two weeks before the 5th of November, or it might have been three weeks, the kids from our part of the estate would all gather together on the backfield.

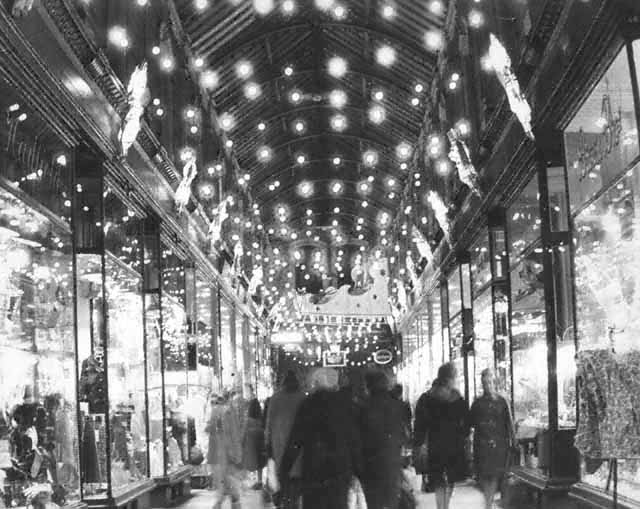

Let me explain about our backfield. I was born and bred on Tintern Crescent, Little Harwood. The houses there all backed on to the field. Our field was surrounded by houses on Tintern Crescent, Kelsall Avenue and Fountains Avenue. At times like bonfire night, I always imagined the houses to be covered wagons surrounding our camp like at the pictures, we were the cowboys. As well as our backfield, which we called the bottom backfield, there was another field further up which we called the top backfield, like ours. It was also surrounded by houses. We never mixed with the top back fielders at the best of times, but at bonfire night we became deadly enemies.

The time I am talking about would be in the late fifties. Money was still tight but it was a golden time to be a child. There were very few restrictions put on us, as long as we came in for our dinner and tea, the rest of the time was our own to go and do as we pleased. We played army in the fields, football and cricket on the reck, chasing games around the streets. But one thing we hardly ever did was to play on the backfield. It was rough and muddy, full of holes and the grass was long. I remember once trying to cut the grass and make a football pitch, but it came to nothing. So the backfield was just used as a short cut from Tintern Crescent to Kelsall Avenue, building bonfires and very little else.

As I said, a few weeks before bonfire night we would gather on the backfield to decide where we would build the fire. This was a ritual that happened every year, but it was always built in the same place. We also would decide who would go with who to collect wood and where we would go and all the other complicated arrangements that go with building bonfires. This process could in itself take a day or two because we always would get side tracked, “let’s go and see if they’ve started their bonfire on the top field,” someone would say. So of we’d go. We’d all make our way to the top backfield. Near to it we would send a reluctant conscript to go on ahead to see if anyone was there, because we knew if there was they would not like our intrusion and would chase us off, better to sacrifice one than us all.

If they had started building their bonfire we would ask the scout how big it was, did they have a guard and other such questions. If they hadn’t started theirs, then we felt good and knew we were one step ahead of the game.

Collecting the wood was always the most fun, or at least that’s what I thought. If you were left as a guard, especially at the beginning before the bonfire began to take shape, it was awful. The guards would be expected to prepare the ground where the fire was to go and guarding an empty piece of grass was not an enviable job. No one, for the first few days, took the job seriously. You might come back and find all the guards gone and the field empty. Those collecting wood might decide a game of football was a better option, and if you were a guard the first thing you would know about it was the sound of a football being kicked on the street. But after a day or two things would settle down.

During the week we would be at school so the business of the bonfire could only be tackled at night and weekends.

The school we attended was St Stephens, which was just a short walk away from were we lived. We could be home in five minutes. On our way we would look for any likely places for wood. On reaching home there would be a quick change of clothes and onto the backfield until teatime. Straight after tea we would be out again collecting wood. There were many places we could go for wood. There were the plots just off Philips road, always good place to start. There was always an old cabin or fence that needed removing and, with a little help, a half good cabin could always be made in to ruined one.

There was one place in particular which always seemed a good bet for wood and that was at the back of St. Stephens Conservative club, where there were the ruins of what I assume was the old stable block that once belonged to Little Harwood Hall. I remember one year getting a real prize there; an old rafter, which had fallen from the roof. The thing was how could we drag it all the way up a rough track and then up Greenhead Avenue? We tied some rope around it and began pulling. After a good hour of back-breaking work, we'd managed to get it to the top of the track, but knew it would be near impossible for us to get it to our bonfire, even with six of us.

Now, on one side of the track there were some sheds. In the top one was a sail-maker. He used to make and repair canvasses for wagons. While we were contemplating how we might drag the rafter up the hill, he drew up in his old van, asked us what we were doing and where we'd pinched the wood from. That’s it we thought, all that hard work for nothing. We told him.

"Right then fasten it to the back” he said and turned the van round. We tied it to the bumper of the van. He was our saviour; he towed it all the way to the backfield, with us kids chasing after him up the road. When we’d got it to the field, he told us to go back to his cabin the following night and he would sort out some wood for us. When we went there was a large pile of wood on one side of the shed and a pile of old canvas on the other.

We took the lot. Going to school the following day he stopped us and asked us if we had taken the canvas.

“Yes,” we answered and thanked him.

“You bl..dy fools, that was for a job I was doing!”

That night we had to take it all back. We would also go knocking on doors, asking for things for the bonfire but we never strayed far out of our area and we certainly would not dare to encroach on the top backfield’s territory, as they wouldn’t into ours. You would always get a good response because it gave people the chance for a good clear out. We wouldn't only get wood, but also hedge cuttings and branches, in fact anything that would burn and although you didn’t like taking this rubbish, you had to take the good with the bad. All this would be transported to the bonfire and gradually it would begin to grow. The guards now played an important part in the process and everybody wanted to be one. The first job you did, as a guard was to build a den and light a fire, then as the wood came in it would be sorted and stacked. Everyone had a turn as a guard. There would always be two or three, usually two big lads and a little one.

I remember once we returned with a load of wood and found the guards had a large pan boiling away over the fire. They told us it was some broth they had made. It smelt good. Using anything to hand we all began to eat it, all that is, except the ones who had made it. When we had had our fill, we asked them where they had got the vegetables from. We realised our mistake. It turned out that they'd used all the old vegetables from the compost heap my father kept on the field.

As bonfire night approached things would become more hectic. Our only goal in life now was to have a bigger bonfire than the top backfield, by fair means or foul.

We began to plot. Plans were drawn up as to how we could make raids on their bonfire and pinch their wood. They were doing exactly the same thing as we were. They to were planning raids, on our bonfire It was just a case of who would strike first! I remember one year when we decided to raid their bonfire. We were determined to strike first and so we plotted and schemed. Some of us would go round to the top of the field, as though an attack would come from that direction; the rest of us would go by the bottom path and, while they were distracted, would take as much wood as we could, and get away. That was the start of a tit-for-tat spate of bonfire raids which lasted right up to the day before bonfire night, when all told, we probably all ended up with our own wood anyway.

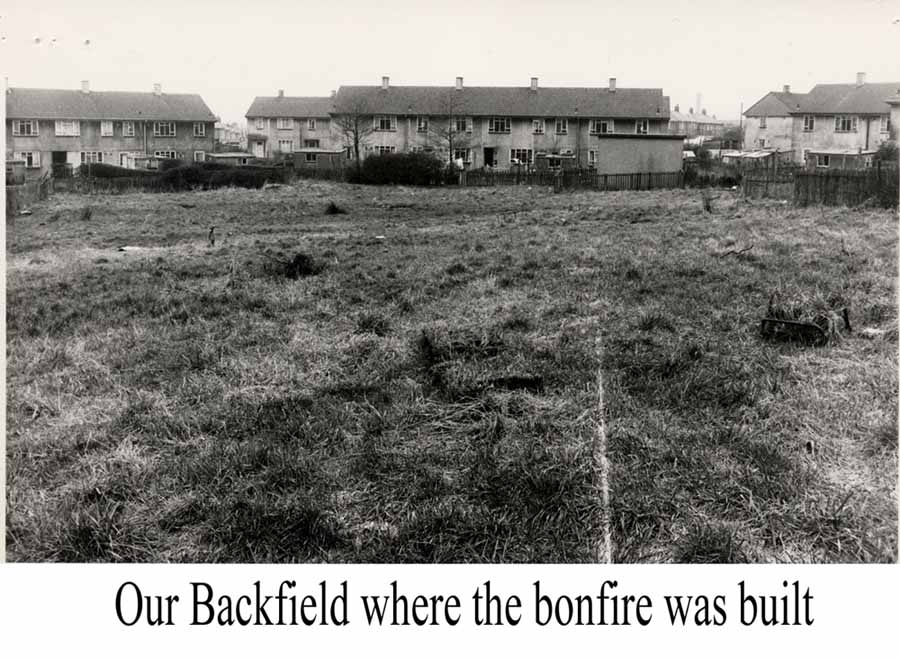

It was not all about collecting bonfire wood; there were other things to be done. The most important of these, after the wood, was the guy! The guy was so called after Guy Fawkes or Guido Fawkes He was the one, with some others, if you can remember your history, who attempted to blow up the Houses of Parliament in 1605, and failed, miserably some might say. He was hung, drawn and quartered for his troubles and was never thrown on a bonfire at all. However it was that same year, 1605, when King James I told everybody to celebrate his deliverance by lighting bonfires, whether an effigy of poor Guy Fawkes was thrown on that first bonfire I don’t know, but later just about everybody else was - the Pope, politicians, and, I have no doubt, the King himself. But at eight or nine years old we weren’t interested in all that ancient history. The guy for us was a money-making venture. The guy’s role, long before he was placed in pride of place on top of the bonfire, was as I said to make us kids money!

Again it seemed like weeks before bonfire night, we would collect together old cloths and newspaper or straw and begin to put our guy together. It was never as spectacular as the one shown above, but was passable, just. It had to be or we’d get nothing. We would tie the bottom of the legs up of an old pair of pants and then stuff them with paper until it had thighs like an all-in-wrestler. Then we would stuff a shirt with more paper, which we would put into a jacket. How to join the bits together would always cause a problem for us. We’d usually let the girls do that bit. The head was always a small bag or pillowcase stuffed with paper, the face being painted either in black paint, or drawn on in charcoal.

One year, we thought the eyes would look better if we used pin-wheels. They made them look big and staring. Unfortunately they somehow went off when no one was there. Probably a spark from the guard's fire caused it. We found it the next day burnt to a cinder. Another time we gave him a cap, instead of the usual painted hair. One of the lads fetched it, telling us it was an old one of his Dad’s. We fastened it on by making holes in it and tying it to the head. It turned out that it was his Dads best flat cap. He was looking for it weeks after, we never said anything though.

The prime object of the guy was to make us money, not just to buy fireworks, although we did use it for that, but also to buy pop and toffee and such things. To achieve this we needed to be mobile. As kids, and living on an hill, we all had flat wagons. We would pick the biggest and best-looking one, usually mine and my brothers, because my dad was an expert at making them. We would use this to transport our guy all round the estate. We were fortunate enough to live near Mullards, probably the biggest employer in Blackburn at that time. After school we would load the guy on to the flat wagon and pull it round to Fountains Avenue and wait like vultures for the workers to come out, which they did in their hundreds, and we would pounce.

“Penny for the guy mister?”

On the flat wagon would be an old biscuit tin which, we hoped, would soon begin to fill with pennies and half pennies or even better threepenny bits and sixpences.

“Penny for the guy Misses?”

The women always seemed to give the most. Men would tend to push through you or perhaps throw a ha'penny. Women on the other hand would nearly all give something, that is, if you could catch their eye. When the rush was over from Mullards we would knock on doors asking for money, but only at the houses in our area. We would, I suppose, make nuisances of ourselves by doing this, but as most of the houses on the estate had children we could always expect a copper or two from them.

Lighting up the Sky

I don’t think they were as strict about who could buy fireworks in those days, because I can remember always having a few bangers that we would set off, but it was much nearer to bonfire night before they started selling them than it is nowadays. A banger would cost a penny and you could have a lot of fun with half a dozen. It would be a lie to say we never got up to mischief with them, or never played dangerous games because we did. On one occasion my older brother put a banger in the lock of a neighbours coal shed door. It exploded like a bomb going off and blew the lock right of the door, but I suppose that’s the sort of thing that kids have always done. We also liked putting them under buckets on the street and setting them off as people passed, which usually made the jump.

Waiting for the night to come was always exciting. I don’t know if we were allowed out longer on the days leading up to bonfire night, but it always seemed like it. We would all sit around the camp fire next to the bonfire with bottles of pop, biscuits and toffees bought with the money we had collected, telling jokes and saying what fireworks we would get, always exaggerating.

There was always one night off from working on the bonfire, at least for our family, and that was Halloween. On that night Dad would take us up Pendle Hill to see “the witches”. Even in those days, the early 60’s, it was a popular place to go and people would flock there. One year I totally convinced myself that I actually saw three witches riding on horse-back over the Nick of Pendle, with their black capes flying out behind them. They were even carrying their broomsticks. It was raining and very dark, but as far as I was concerned they were there. A few weeks ago, while relating this tale to my sister, she utterly surprised me by confirming it. She too remembered the witches on horseback that night, but not the broomstick!

Bonfire night would finally come around. All the waiting and preparation would come together. I can’t remember if we had a day off school, if the fifth happened to fall on a weekday. We would rush through our tea, and then be out onto the field to make any finishing touches to the bonfire. Then it would all be spoiled. All the hard work and time we had put in would be for nothing. I am not talking about it raining or anything like that. I can’t ever recall it raining on bonfire night. No it was much worse - our Dads!

They would come out in force! It would be about half past six at night. They would all gather together on the back field and look at the bonfire we had spent weeks creating. You could guarantee that it would have either been built in the wrong place or the wrong way, so down it all had to come and a complete rebuild performed. We would not be allowed to touch anything. It was now out of our hands. They would send us round to houses to collect stacks of old newspapers that had been put aside for this night, or bits of old wood out of backyards that had been forgotten until now. We could only watch, as our hard work was systematically pulled apart, our den, built into the middle of the bonfire with such care, with its carpet on the floor and if there was plenty of it, lining the walls too, all destroyed. This part of the proceedings would probably take the best part of an hour. A good sturdy centre pole had to be found and secured into the ground, with the rest of the wood being carefully built around that. Finally they would be satisfied. Meanwhile, our guy would have been sitting patiently on its chair waiting to take pride of place on top of the fire. When everything was ready, he would be paraded round the bonfire by us kids with all due ceremony, held over our heads, while we all sang this old song

Guy Fawkes, Guy

Stick him up on high,

Hang him on a lamppost

And there let him die.

All the mothers would have come out to watch this part of the proceedings, some around the fire, but most standing in their own, or a neighbour’s garden looking over the fence. There would be wild chatter and shouting and it would now be dark enough to think about lighting the fire. The guy would be taken from us and, still on his chair, would be hoisted to the top bonfire and secured, while we continued our singing.

Guy, Guy, Guy,

Poke Him in the eye,

Put him on the fire

And there let him die.

Our excitement was intense, now that the time of lighting the fire was so near. We would be getting under everyone's feet, as we ran about in anticipation of the fun to come. The occasional swear word would come from one of the fathers, whose ankles had been caught with a piece of wood that someone was waving around. There were always stray pieces of wood knocking about. The dads would have made a reserve pile of wood, to be put on the fire later. We would take this wood to throw on the bonfire and, if caught, get a clip round the ear for our trouble. Everyone was allowed to shove the paper into the fire. Some of the more careful fathers would tie the paper in knots to make firelighters, but the majority would just crumple it up and stick it in any suitable gap.

Half past seven was the usual time that the fire would be lit. Petrol would have been thrown on the fire and matches or lighters taken out. Brands of paper would be lit, taken to the bonfire and used to light it. There was always that five minutes when you were unsure whether it would burn.

“It’ll never take hold,” someone would say, or “Get more fire over this side, it’s nearly out here,” someone else would shout. But slowly, with the petrol and paper it would take hold. It seemed our excitement could not get any higher, we would be running round the fire whooping like a bunch of wild animals singing

Remember, remember the fifth of November

Gunpowder, treason and plot.

I see no reason, why gunpowder treason

Should ever be forgot.

When the fireworks were brought out, our excitement reached its height. I can remember going with my father for our fireworks and always thinking he’d not got enough of them. He always seemed to leave it until the last minute and it seemed the best had already gone, but we always got enough and they made a good show.

Setting the fireworks off was again a job the dads always performed, at least round our bonfire. A trestle table had been set up for some of the fireworks and milk or pop bottles were there to set off the rockets. I can just remember some of the fireworks we used to have. There were sky rockets, which always seemed to me the best. You could see these exploding in the sky in every direction.

There were Roman Candles which sent a burst of stars into the sky; things called Jack in the Box; and Mount Vesuvius. There was one called an aeroplane. It was small and had wings and was launched from a ramp. All these were set off by the dads, with us watching on. There were some fireworks we kids were allowed to set off ourselves; one you would hold in your hand and wave about, as sparks came flying out. They finished with a loud bang. Others were sparklers, but I think the best we were allowed to set off were what we called “flip flaps.” Whether that was their real name I don’t know. They were made in a zigzag. How we loved throwing them amongst the older girls The flip flap would bang and jump and cause havoc amongst them. They would scream and hold each other in terror, whether real or assumed I don’t know.

The fireworks were generally kept in old biscuit tins, with the lids on and taken out one at a time. They were lit with a slow match, a piece of rope that came with the fireworks. It was lit and would smoulder all night. I remember one of the older boys who had his own fireworks, which he kept in a biscuit tin. He had also got some money, about £3 or so in notes, which he had put in the tin with the fireworks. Unfortunately he was not as careful as he should have been and did not use a lid. Whether it was a spark from the fire, or from a firework, no one knows, but all his fireworks exploded and everything in the tin including his money was destroyed. For a long time afterwards he was known as the lad with money to burn!

Apart from some minor burns and singed hair, accidents were rare. I can only remember one fairly serious event and that was when my sister picked up a spent sparkler. Unfortunately it had only just burnt out and she picked it up at the wrong end. It left a very bad burn on her hand, and a very distraught little girl.

When the fire had burnt down a bit, which was usually after the fireworks, it was time for the potatoes to go into the fire. Mothers would fetch the biggest potatoes they had and they would be put into the embers at the side of the bonfire. They never had a chance of being properly cooked, long before that point was reached, we would, if we got a chance, pull them out with sticks. They would invariably be black on one side and hard on the other, but we loved them and would try to get as many as we could without being caught by a grown up. I don’t think any of them got properly cooked.

My Dad once bought a large bag of chestnuts to put on the fire, but this was a complete failure, as I don’t think we found one of them. Another special treat was treacle or bonfire toffee made by our mother. I seem to think the recipe was something like treacle, brown sugar and lard, or butter. It was made in a large frying pan and then poured onto the cold floor so it would set quicker. it would set like concrete and you would chew until it made your jaw ache.

Finally the time would come when the mothers and older sisters would begin to wander back home. The very young children would be taken with them. Shouts would ring out: “another half hour you kids and then home,” and we would make the best of the time, running round the fire, throwing the last remnants of wood on to it. We would be dirty. Our cloths would reek of fire. Our hair and eyebrows would be singed. Our eyes stung from the effects of the smoke and we would be tired, but we were happy and generally ready to go in.

After we kids had gone, the fathers would stand about for a bit longer and talk, perhaps even have a tot of whisky, if someone had brought a bottle out. Having gone in we would be given a bath and our supper and sent to bed. From our bedroom window we could look out over the field. By now the bonfire would have been given over to the older boys and courting couples. My sister Marian always remembers seeing our eldest brother Bob standing by the bonfire with his arm round his first girlfriend.

The next morning, on our way to school if it was a weekday, we would collect spent fireworks. Was this a throwback to the war when kids would collect shrapnel? We would collect all we could and swap ones we already had and then display them to see who had the best collections. After a couple of days they would all be thrown away and bonfires, guys and fireworks would be forgotten for another year.

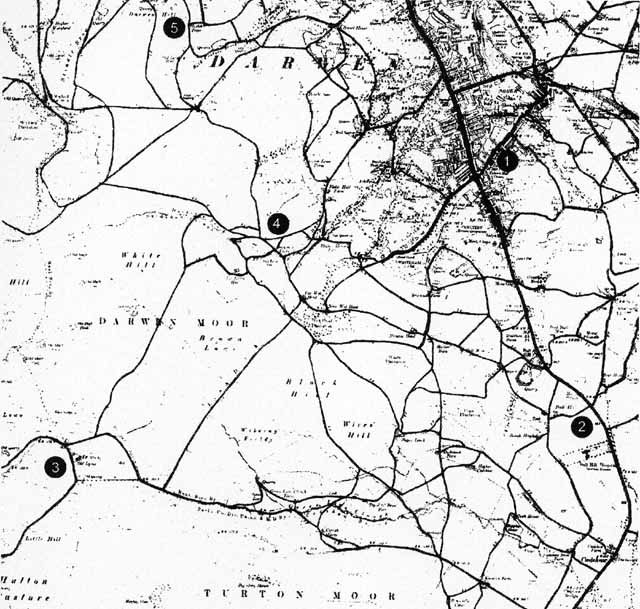

Darwen moors can be inhospitable and dangerous in the winter, painting by Ian Morris.

Greater love hath no man

By Harold Heys

DARWEN'S sweeping moorland has always had a rugged attraction, especially in the summer months when families take to the footpaths and tracks which meander through the surrounding hills to enjoy both the exercise and the fresh air.

In winter, however, the moors can be inhospitable and dangerous, especially if walkers are not prepared for the weather which can change in minutes.

It was much more perilous many years ago when footpaths were rough and ready and when danger from deep gulley’s and old mine workings lurked at every turn.

It was just a few days before Christmas, 1917, when three local lads decided on an afternoon walk on to the moors to the southwest of Darwen after Sunday School at St Bamabas'. It was both adventurous and dangerous for they set off in the face of the most severe blizzard the town had seen for years.

All three were found dead in the snow drifts during the next few days of frantic searching by police and volunteers.

It was a tragic story made even more poignant by the revelation of a selfless act of courage by 16 year-old Ralph Bolton ...

The joint funeral and the formal inquest were over in days and the tragedy was soon pushed into the background as the prospect of another long year of war dominated every part of life - and death - both locally and nationally.

"Self Sacrifice" reads the top line of Ralph Bolton's headstone.

The three lads were William Cooper Longton of Culvert Street, which was close to the church, just 18 and due to join the Army within a few weeks; Ralph Bolton, of Maria Street and his ten-year-old cousin James Bolton of Princess Street - where Mayfield Flats now are.

Why did they set off for the threatening moors when it would be dark in an hour and in weather which, according to the Darwen News was "wild in the extreme" and with "their only shelter the heavens above"?

The paper said: "It must forever remain a mystery." But, looking back now, with old maps of footpaths to hand, it seems fairly clear that the boys simply took a wrong fork.

William was wearing a blue serge suit and a dark, heavy overcoat; Ralph had a blue serge suit, brown overcoat and leggings and little James wore a black suit and a light top coat.

They knew the moors well, but this was precious little protection against the drifting snow and piercing north-east wind.

The alarm was raised that Sunday evening and by dawn a big search was under way. The boys had been seen heading in the direction of Rough Height Farm above Bull Hill Hospital on the southern moors. Snow had drifted up to 10ft and conditions were very difficult.

It was on the Tuesday afternoon that the body of William Cooper Longton was found to the south of Old Lyons farm which was over to the west, on the Cadshaw Brook side of Black Hill and a couple of miles from the safety of Bull Hill. It seems that he had set off to get help and had reached the farm only to find it unoccupied before pressing gamely on.

On the Wednesday, after a slight thaw, the body of little Jimmy was found under drifting snow in the lee of a stone wall about 400 yards to the north of the empty farm.

He was wrapped in his cousin's brown topcoat which had been carefully placed over his own light coat.

Ralph himself, left with just his cheap suit, was found frozen to death about 200 yards away. It seems as though he, too, had set off to get help after making the little boy as comfortable as he could.

In the pocket of the coat Ralph had wrapped around the child was an emblem bearing the legend: "Fight The Good Fight" and, as the Darwen News report asked: "Had he not done just that when he gave his overcoat to his young cousin?"

On the Saturday the bodies of the three pals were taken from their homes to a moving funeral service at St Bamabas' where the older boys had been in the Church Lads' Brigade and in the choir. William had also been the Sunday School secretary.

Hundreds of mourners packed the church and there was no more sad a figure than frail Mrs Nancy Bolton, whose husband Joseph had been killed in action in France the previous summer and who had now lost her only child at the age of just 10.

Hundreds more lined the route to the nearby cemetery, their sadness compounded by the desperation of a continuing and bloody war and the selfless heroism and fine example of a 16-year-old boy.

William was buried with his grandparents. The cousins were interred together, just a few yards away. Ralph's gravestone bears an inscription taken from John 15:13 "Greater love hath no man than he who layeth down his life for another. "

A simple wrong turning in the blizzard looks the likely cause of the tragedy. An uncle of the younger boys and his family lived at Duckshaw Farm above Bury Fold and it was thought that they might have been heading there. It would have been adventurous and dangerous but perhaps not as foolhardy as it had seemed.

As they approached Rough Height a right turn to the footpath through Higher Barn, Meadow Head and Wet Head would have taken them to the safety of Duckshaw Farm before it went dark. From there it was an easy walk home; down through Whitehall or Bury Fold. Instead, above Bull Hill, they pressed on slightly more to the west - and on to their deaths.

The hurried inquest on the day after the last body had been found discounted the theory that the pals were heading for an uncle's farm as it was "in the opposite direction." It wasn't. Duckshaw Farm, where William Bolton and his family lived, was just to the north of Black Hill and the lads had probably simply taken a wrong turn in the heavy snow as the footpath forked..

A moving postscript to the drama was penned by the writer of a letter to the Darwen News a few days later when local folk were still asking what had made them embark on what had seemed such an ill advised venture.

"Such confidence, strength of purpose and love of adventure was obviously displayed by these lads and the crowning sacrifice made by one in giving up his overcoat only emphasised the true British spirit which their elders are displaying every day on the battlefields of Europe."

Everyone has their hero. Ralph Bolton is mine.

1. St. Barnabas'; 2. Bull Hill; 3. Old Lyons; 4. Duckshaw Farm; 5. Darwen Tower.

Article written and researched by Harold Heys.

Harold Heys is a semi-retired journalist who has always lived in his home town of Darwen. An old boy of Darwen Grammar school, he was a journalist with the Lancashire Evening Telegraph before joining the Sunday People where he became chief sports sub-editor and production editor. He retired as editorial systems manager of Newsquest in 2001. He has had a lifelong interest in Darwen and its history and is on the committee of the town's Civic Society. Among his other hobbies he includes horse racing and its history, DIY, snooker, painting, design, writing and computers. He says he is now, in his early 60s, "a professional grandfather."

Reading the pages about Fred Kempster brought back fond childhood memories of visiting this grave and collecting conkers. I recall it was a late summer game played in September.

This coincided with the start of a new school academic year. Collecting conkers was the first thing to do and this was often an evening activity. I did not change into play clothes but went on the conker expedition still dressed in my new school clothes.

There were lots of trees around where I lived in Little Harwood but the best place to go conkering was to the town cemetery. It was a short 15-minute walk from home to the cemetery.

It was a quiet, spooky place. My friends and I felt scared and apprehensive. It was the thought of ghosts and the cemetery watchmen who I called 'Old Sam.' I never found out what he was really called. He would chase you away. If he caught you, you would be in a lot of trouble. Everyone was scared at the thought of police arrest; being scolded by our parents for playing in a place we should not have been.

These fears made our conker expedition all the more daring. It was these fears that made us not go alone. Collecting conkers was a group activity, which was done with your friends. Our fear was conquered by strength in numbers. As well as the abundance of conker bearing trees we also liked to visit interesting graves. The best was the Giant's grave.

My Gran had told me about Fred Kempster who was known as the British Giant. Our first activity on arriving in the cemetery was a pilgrimage to this grave. We marvelled at the length of his grave and exaggerated how tall he had been. We also left flowers on his grave. These were picked wild but sometimes mischief reigned and we ‘borrowed’ flowers from the gardens we passed on our way to the cemetery.

We never disturbed the graves we went by. We treated them with childish respect for we believed bad luck and scary things would happen to you if you messed about. It was okay to hide behind them but not to walk across them. It was for this reason that we checked most carefully the area around the ‘conker’ trees for we did not want to suffer misfortune by accidentally standing on someone’s grave.

Our first task was to search the ground for windfalls. These belonged to the person who found them so it was a free for all in this task. Once this was over there were the ones in the trees to collect. This was a task in which we needed to work together. The way we got the conkers to the ground was to throw sticks or stones into the trees. These missiles had first to be collected and this was a job for everyone.

We would take it in turns to throw the stones into the trees and then collect the conkers the stones dislodged. We would do this for a considerable time until it was judged that we had enough conkers to play the game the following day in the school playground.

It would be dusk as we made our way out of the cemetery. The gates were closed about 8:30pm so we did not want to be locked in and clamber over the wall to escape but more often than not that was how we had to leave for we had misjudged the time.

There was one occasion that Old Sam scared the living daylights out of us. He had seen us collecting conkers when he went to lock the gate. We did not know that he had hidden behind a grave. On our way out he suddenly appeared and we fled in terror and scrambled over the high wall in seconds.

Once on the other side a head count to ascertain that we had all escaped and with our pockets full of conkers we ran home. The scary experience ensured that our annual conker collecting expeditions were brought to an untimely end.

Trouble was in store for me when I got home because my new shoes were now badly scuffed and my new clothes were dirty. I got a telling off and was sent to bed early because of the state I was in.

By William E. Ferguson