The Wild West Comes To Blackburn.

Buffalo Bill's Wild West Show At Blackburn

Written and researched by Jeffrey Booth (Library Volunteer).

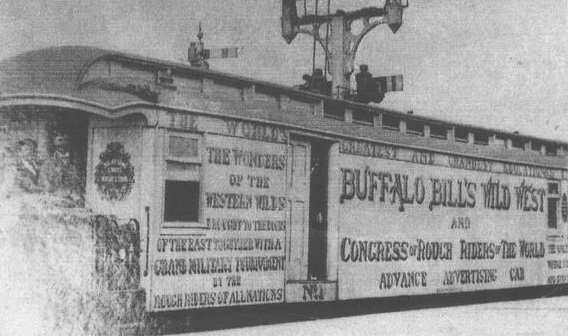

It was early in the morning of Tuesday, 27th of September, 1904 when three special trains arrived in Blackburn consisting of 53 vehicles and weighing 1,000 tons and stretching five–eighths of a mile; this was the world famous Buffalo Bill's Wild West Show.

The living legend, Buffalo Bill (real name Colonel William Frederick Cody of the U.S Army and the Indian Wars) was in town to demonstrate his shooting skills.

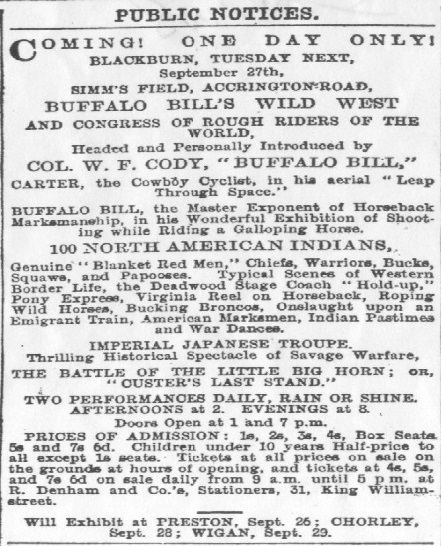

They pitched camp in farmer George Simm's Holehouse farm on the corner of Accrington Road and Croston Street, Blackburn. The logistics of the show are amazing, 800 people and 500 horses in a city of canvas; one baker received an order for 700 loaves, while the horses ate 480 bushels of bran and oats and 6 tons of hay in one day. The show began with a parade on horseback, with participants from horse-culture groups that included U.S. and other military, cowboys, American Indians, and performers from all over the world. Turks, Gauchos, Arabs, Mongols and Georgians displayed their distinctive horses and colourful costumes. The main events included feats of shooting, staged races, and sideshows. Performers re-enacted the riding of the Pony Express, Indian attacks on wagon trains and stagecoach robberies. There was a re-enactment of Custer's "Last Stand" at the Battle of the Little Big Horn and Buffalo Bill played General Custer.

Buffalo Bill made two appearances in the show showing off his skills at shooting objects while riding at a gallop; he was 62 at the time. The show also featured an attack on a settler's cabin by red Indians and Buffalo Bill would ride in with an entourage of cowboys to defend the cabin.

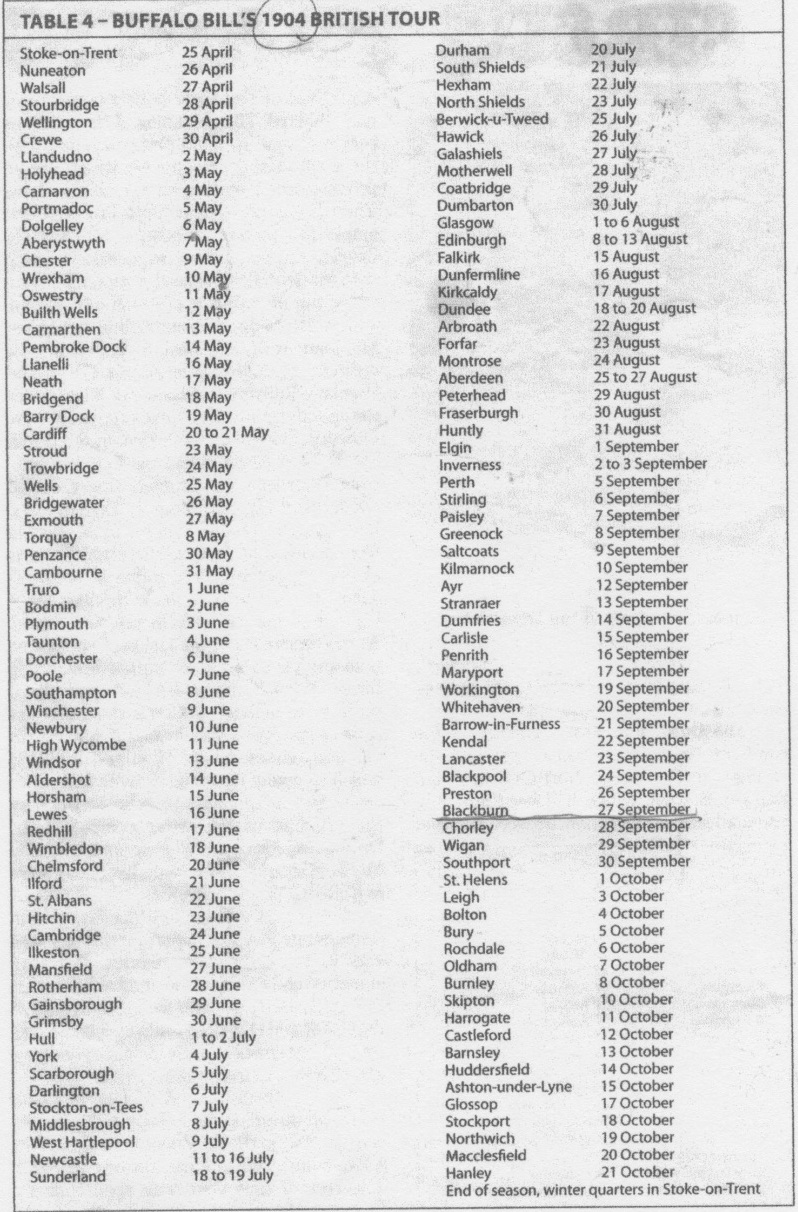

The two hour show was certainly value for money, although with tickets ranging from one shilling to seven and sixpence for a box seat (£5.49 to £41.17) at today's prices, it was a little over priced but it must have been a once in a lifetime experience to anyone who could afford it. It was reckoned that the two shows were seen by 30,000 people. The show started in Stoke-on-Trent on the 25th April and visited every corner of England Scotland and Wales and played in 132 towns until 21st October, two shows at each venue that must have taken some organising.

The Red Indian Who Never Went Back.

When the Wild West Show carried on the rest of the tour, a 26 year old Lakota Chief called Charging Thunder stayed behind. He never returned to his prairie homelands and instead married Josephine, one of the American horse trainers in the show. He settled in Darwen living at 11 Back Duckworth Street and working at the Sankey Pipe Works in Hoddlesden. He had three children two of them born in Darwen. They moved to West Gorton in Manchester, he changed his Indian Name to George Edward Williams after registering with the British Immigration authorities, he worked for many years at Belle-Vue, looking after the elephants, his favourite elephant was called Nelly and when he got drunk, he would sleep off his hangover with the elephants with Nelly standing guard over him. Charging Thunder died from pneumonia in 1929 at the age of 52. His body is buried in Gorton Cemetery. He still has relatives living in Manchester. The story of Charging Thunder was shown on “Inside Out", BBC One on Monday 23 January 2006.

Research from the Northern Daily Telegraph and the Blackburn Times.

A Wild West Invasion, Buffalo Bill’s Visit to Blackburn

A Magnificent Spectacle

The Blackburn Times, 1st October 1904

The visit of Buffalo Bill’s Wild west to Blackburn is an event of the past, but the impressions of that one day when Colonel Cody and his retinue of 800 men and 500 horses, types of all nations, pitched their tent in Simms field, Accrington Road, are indelibly fixed in the minds of the 30,000 people computed to have witnessed the two performances. For more than 20years the last of the great scouts has been touring the world with his unique combination of horsemen and the announcement that he will retire from the role of public entertainer at the conclusion of his present farewell tour of Great Britain in November makes one particularly glad that Blackburn, though so long neglected, was not entirely forgotten. Tuesday last, the day of the visit, was eagerly anticipated by old and young, rich and poor, and great was the desire for favourable weather, which was the making or marring of an entertainment of this class. Ideal weather prevailed, for which the gods be thanked.

The visit of Buffalo Bill’s Wild west to Blackburn is an event of the past, but the impressions of that one day when Colonel Cody and his retinue of 800 men and 500 horses, types of all nations, pitched their tent in Simms field, Accrington Road, are indelibly fixed in the minds of the 30,000 people computed to have witnessed the two performances. For more than 20years the last of the great scouts has been touring the world with his unique combination of horsemen and the announcement that he will retire from the role of public entertainer at the conclusion of his present farewell tour of Great Britain in November makes one particularly glad that Blackburn, though so long neglected, was not entirely forgotten. Tuesday last, the day of the visit, was eagerly anticipated by old and young, rich and poor, and great was the desire for favourable weather, which was the making or marring of an entertainment of this class. Ideal weather prevailed, for which the gods be thanked.It was at an early hour on Tuesday morning that the special trains from Preston, where Buffalo Bill had been showing the previous day drew up in the coal siding off King Street. The transport department is divided into three sections, the first train is composed of 18 cars, the second of 17, and the third of 14: a total of 49 cars, 1044 yards long and weighing 1184 tons. Up before the mill operatives rise to go to their work, early though the hour is at which the cotton and iron worker turns out of bed, Buffalo Bill’s men very quickly had the work of detraining done, and up to about breakfast time, King Street, Church Street, Eanam and Accrington Road resounded with the clatter of horses hoofs upon the pavement, the jingling of bells, and the rumble of the wheels of the heavy baggage wagons. The contingent of horsemen dressed in the heterogenous costumes characterizing their different nationalities was a strange sight. The perfection of the organization of the Wild West is phenomenal. The secret of the rapidity with which the great show is moved from town to town is found in the order and method in which everything is done. First things must be done first, and every man has his allotted work. One of the first caravans to arrive on the field was that in which the cooking is done, so that while the work of erecting the tents proceeded with amazing rapidity breakfast was being prepared. It was a treat to see how quickly the ground was measured out, the loads of timber deposited in the right spot at the right moment. How the workmen spread themselves over the whole arena, and “one man – one plank”, how marvellously a great canvas city rose on ground which only an hour or so before was meadow land.

A story is told of one Blackburn lady determined to see Colonel Cody, though she could not witness the entertainment. This lady sailed for America on Tuesday, and, ascertaining that Colonel Cody was in his van, she went up to the door and asked for an audience with him. This was willingly granted and, face to face with the man she was seeking, she told the great scout that, as she sailed for America that day, she would not be able to see his entertainment, but she would like to shake hands with him. Buffalo Bill laughed heartily and gave the desired handshake, and the lady went away contented. Short though his stay was in Blackburn, Buffalo Bill had innumerable requests for his autograph. It was quite a treat to have a peep in the great dining tent at mid-day. The entire staff dine at one table, with Buffalo Bill in the centre. All enjoy the same good fare excellently cooked and served up with greatest cleanliness. Indeed, the commissariat department is an important part of the exhibition as can be readily understood when we mention that there are 800 human beings to feed.

The stud of horses, which occupies two large tents, is very large and admirably selected. The horses for the Wild West performance occupy one tent and almost all of these are Bronchos the handy lithe clipper-built saddle horse of the Far West, which can do a long strong gallop without distress, finishing fresh and fit. The Bronchos, which are saddled with the light hollow American Army saddles with broad cord knitted belly bands, which cannot slip and are perfectly comfortable to the horse, which are mostly brown and bays, greys and whites. They are well bedded, fed on the best, and every horse is fit and hard, with a fine distribution of muscle over the confirmation, limbs as dense as steel bars, springy fetlocks, and hard, shapely feet. In an adjoining marquee are the team horses. They are various grades, all in solid condition. No whips are allowed. In connection with the foddering of the horses it is most instructive to learn that they consume in a day 240 bushels of oats, 240 bushels of bran, and six tons of Canadian hay at £5 12s. per ton. The straw for bedding comes from France and costs 9s. per quarter.

An hour before the afternoon’s performance began Accrington Road was alive with vehicular traffic and crowds of people walking to the camping ground. Special tramcars were run, and whilst these in quick succession put down their loads of sixties, hundreds more used the wagonette, the cab and the humble bicycle as means of reaching the show ground. There was no recognized suspension of work, but in some instances the workpeople took French leave. A large staff of police was on duty regulating the flowing traffic. The Wild West is open to the sky and the audience sit round three sides of the amphitheatre under a canopy which answers the dual purpose of a shade and a protector according to the hour and climatic conditions. No one could quibble with the weather on Tuesday. As to the two hour programme there is so such an abundance of it compressed in such a way that it is best considered in its totality. Perhaps we cannot do better than a quote which appears at the head of the official programme - “An exhibition, the intention of which is to educate the spectator through the medium of animated pictures in the picturesque life of the Western American Plains in the days just past, showing primitive horsemen who have attained fame spiced with their counterparts of modern military horsemanship, all combined in an evening’s entertainment, rendering the reading of books or viewing the works of sculptors and artists on the subjects more easily comprehended and enjoyed in years to come” - . The Cowboy Bank broke into music, the last note of “The Star-Spangled Banner” had been played and the Congress of the Rough Riders of the world began.

No one will say that Colonel Cody keeps the best things till the last, and by that we do not infer that he puts his best apples on the top. Led by a band of whooping Indians, the representatives of the different tribes and countries dashed break-neck down the arena, and the air was loud with the thud of hoofs and the clash of arms. The Indians, big muscular men, with jet black hair streaming in the breeze were almost all in their primitive habit their naked skins being coloured and crossed with all the designs of savagery. Feathers streamed from their head-dress and scanty costumes, and they carried their native implements of war. For several minutes the notes of the particular tribal music fell quaintly upon the ear. Arabs, Mexicans, Cowboys, Americans and English cavalry, and the elusive little Jap and for whom the audience had a special cheer followed in what had all the appearance at first of a stampede, and lined up to receive their organizer and General, Colonel Cody who rode to the head amid the applause of the of the entire audience, and formally introduced the Congress of Rough Riders as the performers of the day. The site was a magnificent one. Then the horsemen broke into ride and carried out a variety of evolutions. This act in the programme opened up, as it were, the individual life of the sections.

As the show is a Wild West one the Indians claimed prior attention, and many acts of their savage life were dealt with in a variety of realistic ways. Not only was the blood thirsty nature of the life of the frontier men dealt with there were many examples of its peaceful side, or not altogether its peaceful side, but its social side that stamped the exhibition with a higher motive than that of appealing to passions. The various methods of riding practiced by the different nations were a source of great interest. The Arab for instance came naturally into prominence and the manner in which the son of the dessert utilized his Arab steed was shown in striking comparison with the Cossack, who, if less historically speaking attached to the animal is nevertheless a wonderful rider. Dashing around the arena the Cossack firmly fixed in the girths with his feet stood upright and hung and dragged under the horse in a way that would give an enemy a small chance to “pot” him in conflict. In the opinion of many the Cossack’s was the most daring of all the examples of equestrian riding seen during the afternoon. The Cowboys came in for a great reception and the way they controlled the bucking Bronchos was sufficient in the show that no power on earth could make the Cowboy come out of the saddle till he wanted to. There was some fine bareback riding as well by Indian boys and an exhibition by American girls from the frontier, who, with one exception, rode astride and with a very graceful seat.

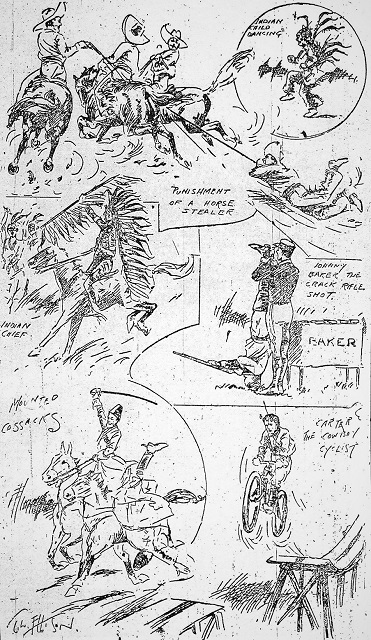

The acts that showed a more stirring side of prairie life illustrated pony express riding, a form of thing that obtained in the West before the railroad and telegraph line. The dangerous duty of carrying the mail was finely illustrated and as Colonel Cody began life with the Express the turn had quite a graphical interest. Outside “Roaring Camp” or “Poker Flat” might have been seen the cavalcade of an emigrant train crossing the plains just as it travelled round the show ground. There was an attack by the Indians, the fire of 100 rifles and the blood curdling cry of the red skins. The scouts and cowboys engaged them and the audience applauded the mimic conflict by reason of the realism with which it was invested. An act of retributive justice was meted out to an offending horse stealer, and this furnished an amusing and thrilling turn. The thief escaped only to be lassoed, brought to the ground, and dragged at the heels of a horse at full speed, as if he was a bag of sawdust, and riddled with shot. Of the many interesting examples of skill, perhaps the Mexican lassoers came in for more than their fair share of notice. Ranch life in the West and the attack of the Deadwood mail coach gave Indians another opportunity of exhibiting their partiality for blood, and the stirring representation of the historic stand of Colonel Custer was a style of tableaux that appealed to the audience. When the various acts had been endorsed the spectator felt that he had learned some of the life of the Indian and the history which formed such an enterprise of Colonel Cody. A company of veterans spare of so many minutes than he could have gleaned from the books of a library in years and this after all, is a reason why we ought to be thankful for the enterprise of a Colonel Codey. A company of veterans of the United States Artillery with the old muzzle loading cannon and a company of the U.S life saving apparatus gave rapid ex-positions of their work. Johnny Baker and Colonel Cody furnished the marksmanship of the Wild West. Both have the proverbial eagle eye, and their performances were wonderful. The Cowboy cyclist who leaps a chasm of over 50 feet makes the audience hold its breath and be thankful for the fact that it is only a matter of seconds. The reception given to the whole of the performers was hearty in the extreme. At night, under the influence of the electric light and before an even larger audience, the Wild West was repeated. By midnight all traces of the show had vanished from Blackburn as if by the magic of Aladdin’s Lamp only to reappear at sun-rise next morning in some other town miles away.

Transcribed by Philip Crompton

Notes on Photography for Amateurs

By “Aremac”

Cameras at the Buffalo Bill Show

Blackburn Times October 1st 1904

I noticed several hand cameras at the Buffalo Bill exhibition on Tuesday afternoon, their owners no doubt having had it in their minds that there would be offered to them countless subjects for snap shots which (if they came out alright) would make excellent souvenirs of the show. Some, I was aware, had brought some extra special rapid plates for the occasion, and seeing that the light was not really bad doubtless expected that all would be plain sailing. But the first rude shock was given to the nerves when upon entering the marquee they found that between the performers and the seats arranged for the comfort (two hours of sitting proved them to have been made of very hard wood) of the spectators was a perfect network of ropes and poles which I seemed almost impossible to avoid showing in the photograph, whilst the fortunate occupiers of the best seats were unfortunate in having to dodge the sloping track upon which the hair raising feat of jumping several feet in to the air on a cycle was accomplished. The distance having been mentally measured with a careful exactitude that did them real credit. The focusing of the camera having been arranged accordingly, and the shutter set at a speed which it was calculated would not be too quick for the light of a late September afternoon and yet not to slow to show movement amongst the galloping horses and the bucking bronchos, they were ready for all comers. And then the band played, and the show commenced.

Not Appreciated by the Officials

Click! click! went the shutter, and clang! clang! went the plates as they fell in rapid succession to the bottom of the camera. Colonel Cody was of course the attractive subject from the camerist’s point of view, as he rode up in front to introduce to the public his famous rough riders there was a simultaneous click of shutters that would doubtless made itself heard for some distance had there been a few more. One enthusiastic amateur, not content with the view afforded to him from his seat, risked his reputation by sliding quickly in front of the seats near to the rails and “snapped” the colonel in his most striking attitude as he raised his hat and commenced his little speech. A stern official, however, strictly forbade him to attempt to repeat the experiment, and he retired to his seat evidently feeling satisfied in his own mind that he had done a smart thing. Another amateur, who had carried his instrument from the other side of the town, was quite not so fortunate. He was going to take such a lot of nice pictures, but he was sorely disappointed. A dutiful official told him in kind but firm language that photography was not allowed, and that the coloured picture postcards he saw displayed were not being distributed free but were being offered for sale at the price of sixpence a set.

Some Mystifying Results

I have just had the delightful privilege of inspecting a few of the interesting negatives secured on Tuesday. Tis a pity some of them are under exposed, but I am nor exaggerating one bit when I say that, with the aid of a powerful magnifying lens, it is quite possible to make out the feathers of some of the redskins, but again tis a pity that considerable movement is discernible amongst the riders. Yet there is something particularly striking about the large tent poles in the near foreground, which stand out against a white sky with startling clearness, relieved by the criss-cross of ropes which cover the plate. There has been a dispute over one of the negatives as to which is Buffalo Bill. Three persons guessed three different figures as representing the famous Wild-West showman, and it eventually resulted in an a “toss-up”. Another amateur exhibiting with some pride a print, which he solemnly declared was a photograph of the Deadwood Mail Coach being attacked by Indians lost a bet through being too emphatic as to the correctness of his hasty conclusion. He was afterwards compelled to admit that it must have been a van used in the cowboy’s encampment arena.

Transcribed by Philip Crompton