Does anyone out there remember this Blackburn rag and bone man? His real name was Tommy Thompson, also known as Tommy Blackledge.

Thank you to Cottontown reader Phil Calvey who has sent his memories:

I remember our subject very well from when I was a small boy. I was born in Darwen in 1949 and lived on the main road ( Blackburn Road) in the Lynwood area until 1964. Valderee was one of our regular rag and bone men and I was overawed and perhaps a little frightened by his flamboyant dress, his eccentric behaviour and loud singing. He got his name so I was told because of a song he regularly sang that was popular in the early 1950s " I Love To Go Awandering” Personally I never heard him sing that song but he certainly had a large selection of other song to choose from. His call as he walked down the rear alleys or "backs" as we called them was I think EEERAGBOOAN!! As you can see from the photograph he was gipsy like in his dress. I can see him in my minds eye dressed in summer with a red and white spotted neck cloth tied around his neck ,his trilby worn at a slight angle, a collarless shirt underneath a waistcoat with the shirtsleeves rolled up and brown moleskin trousers with string around the bottoms and big army boots. He stood very upright and had a very military bearing. In winter he had a long tatty overcoat almost down to the floor and also his trademark hat and neck cloth. He pushed a handcart and on this was a small very second hand cupboard in which he kept various coloured pumice stones for dressing the front steps, yellow and cream ones spring to mind, which he gave for any scrap he received. Later on the handcart was replaced by a tall old fashioned coachbuilt pram.

My Mother states that he was always well mannered and if he met a lady whom he knew he would doff his hat and bow deeply to her as a greeting. My Father confirmed his name as Tommy Thomson because they both went to the same school and that was St George's Junior School, Darwen. Father described him as a quiet pupil and individual. Tommy joined the army in WW2 and Father thinks that he was in one of the glamour regiments, the Guards or the Paras ,but Tommy had a bad war and returned a very changed and troubled man. I think he struggled to settle down after the war and rumour alleges that he had been committed to a mental hospital for some time but that is only a local rumour which I cannot confirm.

Another Cottontown reader shares her memories:

I also remember Valderee from my childhood he often frequented the streets of Little Harwood and always stopped to chat to my grandmother. He often passed by St Stephen's school and waved at all the children. I found him quite fascinating. An uncle of mine always warned me not to speak to him as he was a bad man. When I was older my uncle informed me that he had once stabbed someone many years before and was a violent man,how much truth is in that story I don't know but my uncle was not a man to exaggerate, however I always found him fastinating as did all the children who flocked around him. He never harmed any of us. I also remember a tramp called George who lived in Elm Street in the 70's. You would often see him feeding the pigeons outside what was then the Regency Pub later known as the Cocunut Grove. He was known as Dirty George around Little Harwood. He was a shy gentle giant of a man who wore a dirty string vest and a brown overcoat which was tied with string. I also remember the man who stood outside the White Bull in the 70's next to the subway selling the telegraph shouting TELEGRALF! (or words to that affect). Happy memories!

A big thank you to cottontown reader Barbara for sharing this lovely memory:

This is really fantastic, i am an artist and i am currently working on a piece of art work relating to a childhood memory of mine the local rag and bone man. I lived in Blackburn Copperfield street near audley range in the 1960\70s i am 44 years old now but my memory of the local rag and bone man Val-de-ree has never left me. i remember he had an old delappedated perambulator the ones with big wheels and suspension. He would push this old pram down the street yoddle ing at the top of his voice, yoddle he ho ho!!

he wore an old hat with a feather sticking from it and would stop and chat to the mums on the street seeing what old tat they would pass onto him to add to the enourmous pile of tat he already had in his pram. i remember lots of old dolls and old toys tied to his pram they were all on my eye level jangling arbout because i was about 5 years old, he may have had a bell to ring as well.

when all us kids would see him coming we would shout his name and follow him down the street, he would stand there looking and laughing at us and blowing rasberries from his mouth making rude noises always used to make us laugh and blow rasberries back at him. what a fantastic piece of local history that will never repeat itself again.

I was reading an article on your website when I noticed somebody had mentioned a person in 1960 who sold newspapers on the the old White Bull corner in Blackburn .This chap who he mentioned was my grand father, Joe Lewis. He sold newspapers for more than 50 years during his career as a seller which began with the Northern Daily Telegrapth in 1910. He took pride in the fact that he never missed a day. His biggest sale of his total 7,000,000 came on the First World War Armistice Day when he sold almost 8,000 copies.

My grand father Joe was a well known person in Blackburn.He stood on the pitch on Railway Rd for almost five decades in rain, hail and snow, starting from 5.30 in the morning.His famous shout for selling papers was yup .He served Blackburn well.I have no photographs of Joe, although the Telegraph took photos of him over the years he sold papers for them .He died in 1970 through a car accident.

My father William Barnes who was always known as Ginger, knew Valderee well as he was also a rag and bone man. That's how I got to know Valderee. There were a lot of characters in Blackburn then and the older generation will always remember them

Some more memories from another reader, Ernie-

I use to drink at the Aqueduct pub on Bolton Road in the late fifties and early sixties, where Val-de-ree used to frequent the vault. He would open the door and shout "val-de-ree" and the younger ones would shout back "val-de-ra". How he got away with wearing a trench coat with a bandalero and bayonet in a scabard, I'll never know. What a character!

Peter S Farley Recalls

I remember seeing Val De Ree during the late 1950s as he walked about the Vernon Street and Kay Street areas of Darwen. As I recall he wore a leather belt around his trouser-top. Attached to it was numerous military cap badges. He also carried a bayonet and scabbard hanging from his belt. The local story was that he was suffering from shell-shock. It was said that he had been a Royal Marine during WW2 and because of this the Police allowed him to carry the bayonet. He wore gum-boots or wellingtons as they are usually called and their tops were turned down to expose the inside canvas. Standing on what was Vernon Street, was a small Sunday school. For some years during the 1960s it became an M.O.T. testing centre for automobiles. At the rear of the building were a few short streets of terraced houses. The streets had names such as Star, Sun and Moon. There was also a small factory called ‘Haydocks’ which manufactured soft drink. Immediately behind the ‘Sunday school’ aka M.O.T. centre, was a scrap yard. It was there that Val-De-Ree would take his collected scrap iron. He pushed a hand-cart and he also had a dog, which faithfully followed him about. The dog was named ‘Flash’. It’s breed was something like a collie and of slight build. The dog was well known to the public and made headlines in the Lancashire Evening Telegraph when he died. If I remember correctly he was hit by a motorist. There was a small photo of the dog printed on the front page, with the head-line simply saying ‘Flash Dead’. May they both rest in peace. 03/01/2025

If you have any memories of Val-Dee-Ree or any photos we’d love to hear from you, so we can add them to the site.

Please contact us at Cottontown

The article was printed in the Blackburn Times 18th March 1905, a decade after Edward Sharples death. There is no indication as to who the author A. B. E may have been.

BLIND NED

By

"A.E.B.

A brief account of the once well-known individual who bore the above appellation will probably be of interest to those who love to study the short and simple annals of our local peasantry.

Edward Sharples, better known has blind Ned, was born in 1822, one of four brothers—John, Richard, and Peter being the names of the three others. His father belonged to the yeoman family of Sharples, who were farmers at Putforth (locally pronounced Pufforth), Lower Darwen, for close upon 150 years. He died in 1831, having been previously sold to the Water works Committee of the Blackburn Corporation his share of the land in Spa Brook Bottom for £3,400. Blind Ned and his brothers were all four fine, strong, and well-built men, with scarcely a straw to choose between them as to height or weight. Many stories are told of the quartet and their youthful pranks which are well worth recounting, but for the present Blind Ned must receive our sole attention.

When he was five years old he went to peep through the key-hole of a cottage near Belthorn, when a little girl about his own age pushed from the inside a sharp steel spindled, known locally as a “hotzel,” which penetrated into his right eye, at once half blinding him. Soon after this occurrence the other eye became inflamed and eventually Ned lost his sight entirely. At ten years of age Ned had to begin to earn his living, and as two of his brothers were shoddy (cotton) manufactures at a small mill situated on the side of the tiny rivulet coming down from Spa Brook Clough, he obtained from them work at suitable jobs, mostly of a laborious nature. Here he developed great bodily strength, for he had to assist in carrying bales of cotton shoddy from the mill at Dick Bridge up to the top of Daub Hill, where the cart road commenced. He also helped his mother on the large farm known as “Eden,” and thereby developed an extraordinary sense of touch which enabled him to be a better judge of cattle and horses than most of those who possessed good eyesight. He could even detect differences of colour in the hides of the animals and proved this in a transaction at Brough Hill. When he was twenty-seven he attended this fair to buy cattle, and bought no less than 70 beasts, all about a year old. The man from whom he purchased the cattle could not believe that blind Ned was able to tell the colour of the hicks by touch, and he volunteered to knock 5s a head off the price if Ned would name the colour of 30 out of the 70. But Ned performed the task easily and thus saved £17 19s, afterwards re-selling the whole lot to Mr W. Hindle of the Brown Cow Inn Livesey.

Once for a wager he undertook to tell the colour of any cow in the shippon at the Red Buck, Oswaldtwistle. Blind Ned was led into the shippon and a du-coloured cow was selected out for his judgement. He ran his hand softly over it and named the colour correctly, then passing his hand under the belly; he found and named a white patch thus easily winning the wager. The challenger after his return to the inn said somebody had told Ned the secret of the two colours. This so incensed the blind man that he struck the challenger a blow from the shoulder which knocked him into a big chair and broke it to fragments.

As a young man he “kitted” milk into Blackburn. Some old inhabitants of Grimshaw Park tell of his driving down the road a good rate of speed, carefully avoiding collisions by his acute sense of hearing, his great round face beaming with intelligence, though deprived of his principle attraction, the eyes. He both rode and drove many thousands of miles, and it is stated that he could draw up within a yard of his destination. An old toll-bar keeper says he has seen Ned drive his horse up to a foot off the gate and stop suddenly whilst he himself was greatly alarmed lest the horse should smash down the gate, but Ned only laughed. His knowledge of the country around his home was really wonderful. Men tell that when they were lads and trespassing on the farm Ned would follow them, no matter which way they went, just as if he could see them. Blind Ned lived at the old house which stands nearest to the Yate Bank Reservoir, perhaps better known in the district as Dick Bridge Reservoir. The road from Daud Hall to Holehouse used to cross the by-wash by a single loose plank nine inches wide, which served for a temporary bridge for over 60 years. Blind Ned had crossed it in all weathers, and at night had often guided or carried his neighbours across upon his back.

He thought no water equal to that which rises at Ooze Castle, high up the bank, and which runs down Spa Clough, ultimately forming the reservoir. At one place is the ravine just below Windy Bank Farm, called Rock Hall, can still be found turkey or oil stone suitable for whetting purposes, and one of those stones was a favourite gift of Ned’s to his farming acquaintances.

In his prime he was 5ft 10½ in high and 230lbs weight, 43 inches round the chest being altogether a fine specimen of lusty manhood. His brothers though equal to him in height and general appearance, never possessed his mighty muscles and frequent wagers were made upon his feats of strength which he was never loath to display, being very fond of rough amusements. He possessed a double set of teeth, generally an indicator of physical strength and one of his favourite feats was the lifting of a sack of flour—240lbs—with his teeth alone. Once, for a sovereign, he lifted and carried for 50 yards three sacks of flour—one under his right arm, one upon his left shoulder, and the other held by his teeth. It was a common occurrence for him when he came to Blackburn Market to lift a 27 gallon cask over the top of his cart wheel. Travellers tell of the enormous weights the Turkish hamlas or porters of Constantinople can carry with their enormous practice, but the greatest weight mentioned by them is 448lbs. This was once exceeded by Blind Ned, it occurred in this way: a man named John Maden, a spinner at Dick Bridge Mill, was taunting Ned about his carrying of the heavy bales of shoddy which were made there, and a big bet ensued on Ned saying; “will carry every ounce of weft that this man Maden roves off a one-hundred spindle-billy in a week in one load.” The rover strove hard to win the bet by working with all his skill throughout the week, and on Saturday Ned was watching to see that he did not work longer than the appointed time. He stopped his billy a minute or so after the hour had expired to doff his sett but as it meant 25lbs more weight, Ned said “Maden tha morn’d doff.” The week’s work was packed in a huge bale and put upon the scale, when it turned the beam at 572lbs, which ponderous load Blind Ned carried not on the level but up a steep hill to the cart at Daub Hall.

Another feat was “ringing the fifty sixes” which was a pet feat of Ned’s. It was performed in this manner; three fingers of each hand are inserted in the lifting ring attached to the weight, the arms are slowly raised until both the weights hang over the head, when they rung by banging them together. Blind Ned had done this as often as six times, a performance which Sandow* can scarcely equal. Ned’s brother John, who—people say—was as good a carter as ever cracked a whip, once brought a load of 30cwt. of cotton from Blackburn to the top of the old lane leading down to Dick Bridge. To bring such a load down in winter was very dangerous, so John left it there all night. It was then the practice to trail a rude sledge down behind the loaded cart with a pack of meal or flour upon it to act a sort of drag or brake. In the morning, Ned, who was then only eighteen, undertook the task, although the road was in local parlance, “a whirl of ice.” His horse, Rowley, almost as sensible a Christian, planted its feet firmly for the dangerous descent, whilst Ned held its head with his left hand, and also acted as brakesman with all his giant strength. But the man, cart and horse, all three slid from top to bottom of the lane without a halt. Not a hair was injured, but his narrow escape from death or disaster often sent a thrill of emotion, upon remembrance, through the mind of Blind Ned.

He was a frequent visitor to the bi-annual fairs in Blackburn, and as he sat in the “Anchor” or “Three Crowns” in Darwen-street old public-houses which have now disappeared, he could recognise any of his old neighbours or friends, either by voice or footfall, before they entered the room. Having very long arms and being of great girth round the chest, he was a clever hand at what is called “fathoming,” that is reaching in height or breadth. At his old home there was a beam in the ceiling of the low Kitchen just six feet from the floor. This, Ned could rest his fingers upon whilst those of the other hand lay flat upon the floor. He could fathom seven feet ten inches in height, but was beaten once by a man named Farley, who kept the St. Leger Inn, King-street, about 60 years ago. This Farley had the largest hand Blind Ned ever saw, and Ned said that if anyone else saw one larger they never told him. Other feats of this local Samson still lingering in memory are the lifting of nine successive loads of potatoes and throwing them over his head, the lifting of a stone weighing over three cwt to form the roof of a porch at the farm and the winning of several walking matches, notably two with another well-known Blind man, Blind Tom of Haslingden. We are told that fancy dinners and elaborate cooking were nothing to Ned, he had always been used to hard bread, cold bacon, and buttermilk, with an occasional “prato pie” as his chief diet. He attributed the good condition of his teeth and his stomach, even when he was an old man to his abstention from tea and heavy feeding. At the time of his death in February, 1895 aged 72, he and his wife were all that was left of the Sharples family living upon the family copyhold estate. He was buried at St. Paul’s Church, Hoddlesden, and as the lease had expired, his wife also died some years ago in very impoverished circumstances. None of his sons survived him, and his two daughters both are married, one Ellen, living in the United States, and the other Mary is the wife of a man named Thomas Yates, who in 1890 kept the small farm and inn known as the “Star,” properly the New Inn, at Daub Hall, Pickup Bank. Several of Blind Ned’s Nephews are in business in Blackburn, notably Thomas Sharples, the hatter, in Darwen-street. Many of the circumstances here narrated are taken from a scarce pamphlet of religious experience published some 20 years ago [1885] by William Lee of Haslingden. Such is a portion of the history of a remarkable character fully as celebrated locally as his eminent prototype “Blind Jack” of Knaresborough ϯ.

*Eugen Sandow (April 2, 1867 – October 14, 1925), born Friedrich Wilhelm Müller, was a German pioneering bodybuilder known as the "father of modern bodybuilding".

ϯBlind Jack of Knaresborough: (1717–1810), born John Metcalf, also known as Blind Jack of Knaresborough or Blind Jack Metcalf. He was blind from the age of six, and was the first professional road builder to emerge during the Industrial Revolution.

This type of article is not uncommon for the time, religious tracts were often written to show how people, mainly men, could overcome handicaps either physical, such as blindness, deafness, loss of limbs, or self-inflicted caused by drink or debauchery. It gives us a rosy eyed view of a man who although blind makes up for it by his other senses being enhanced. It shows how he overcame his handicap and performed countless acts of unbelievable strength and with his sense of touch so refined he could tell colours. The religious pamphlet mentioned may not now exist.

How much of the article we can believe it is now imposible to say, some of his deeds do look rather over stated, but I have no doubt there will be some truth in it.

The few bits of information I have been able to find out about Edward Sharples I have laid out below. From it we get another side of "Blind Ned", which is not altogether endearing to him.

Edward was the son of Thomas and Dorothy Sharples (Nee Greenwood). The couple had been married at Blackburn Parish Church (St. Mary the Virgin) on the 25th June 1815. Thomas was a farmer. The article implies that Thomas and Dorothy only had four sons but there were also three daughters. The sons were John, baptised 21st January 1816, Richard, baptised 11th February 1818, Peter, baptised, 28th April 1824. The daughters were Betty, born 31st May 1820, Ann, born, 21st December 1826 and Mary Jane baptised 24th August 1831. Edward, the subject of this article, was baptised 20th March 1822. The article above says Thomas Sharples died in 1831, but according to the 1841 census Thomas (45), Edward, Peter, and Mary Jane were living at Hole House, Yate and Pickup Bank, the 1851 census also shows that Thomas was still alive and living at Guide.

His wife Dorothy is not on the 1841 census and on investigation I found that she died in June 1837 and was buried on the 17th of that month at the Parish Church. I cannot find a date of death for Thomas.

Edward, as the article points out, became blind at the age of five. The 1871 census also shows he was aged five when he lost his sight. It is also worth recording that the 1851 censusshows that his wife Betty was deaf, but no other census record says this.

Edward was born in March 1822; all we know of his childhood is what is reported in the article. It is doubtful if he could write, he could only make his mark when he was married, and being blind from such an early age he probably never read.

On the 25th of July 1841 he married Betty Beckett at the Blackburn Parish Church. Betty was the daughter of Francis and Betty Beckett (Nee Dearden) and was born in 1823; Betty's father was a grocer from Blackburn. The 1851 census shows Edward and Betty living at Lang House, Pickup Bank, Edward is a 29 years old, a farmer of 18 acres and a beerseller. There are two children Dorothy (5) and Ellen (8 month). I cannot find any sign of him on the 1861 census. The 1871 census shows Edward, (49) Betty (47) and their daughter Mary Jane (15) living at Hole house, Yate and Pickup Bank. Edward is still a farmer but now is only farming 9 Acres. The article intimates that Edward and Betty had sons and two daughters; however, it seems he had no sons and three daughters, Dorothy born c 1846, Ellen born 1850 and Mary Jane born c 1856.

It would also seem that the family spent time in the workhouse. At a meeting of the Guardians held on Saturday 9th June 1855, there was an altercation between certain Guardians and the Governor. William Durham asked the Governor (Mr Charnley) whether some [toys] wheelbarrows and cradles had been made by one of the paupers for certain guardians. The pauper in question was Blind Ned who had made the toys for Mr Boyle and Mr Watson. When asked if payment had been made for the toys Mr Charnley said; "No, there was no payment made but to Blind Ned. I thought that there was no harm in his getting it as tobacco-money."

Then in the Blackburn Standard of 15th September 1858 it says; "Among application for relief was Betty Sharples, wife of Edward Sharples, better known as Blind Ned, farmer at Yate and Pickup Bank, whose matrimonial differences have on several occasions recently required magisterial adjudication. The circumstances of the applicant being explained to the board, they made an order for 5s a week, the money to be recovered from the husband." Then again in the Standard of 29th December 1858, at the workhouse Christmas dinner:

"Upwards of 250, [inmates], including men and women, boys and girls, assembled in the [workhouse] dining-hall about noon, and were regaled with a bountiful supply of roast beef and plum pudding...Dinner being over and grace after dinner having been sung, as grace was before dinner, "Blind Ned" got up on the end of a form, and in a protracted series of addresses proposed thanks to the guardians who had ordered for them the excellent dinner of which they had partaken; thanks to the friends who had so kindly come to wish them a happy Christmas; thanks to the master and mistress, [of the workhouse], and schoolmaster and schoolmistress."

It would seem then, that far from being a farmer of some means (able to buy 70 cattle) he was, at least some of the time, unable to support himself and his family. This may be the reason he and his family cannot be found on the 1861 census, (only initials were used for the inmates of the workhouse in this census.)

Blind Ned appears three more times in the newspapers; the first is an action by Edward Sharples against Michael Walsh and Edmund Harwood. Sharples had sold a pony and cart for £10 to Walsh and Harwood on the understanding that if the pony should foal they would pay Sharples an extra 15s the pony did foal but they denied that this agreement had been made and there being no proof Blind Ned lost the case. In November of 1862 Blind Ned was in trouble this time with the police! He was accused of stealing a hay-knife from the barn of Mary Dearden, an innkeeper at Oswaldtwistle. The knife was recognised when in the possession of Blind Ned by three marks cut into the handle. Ned denied stealing it but the jury at Preston Intermediate sessions did not believe him and he was sentenced to 1 month in prison.

He was in trouble again in May 1866, this time with another farmer named James Townend. They were accused of stealing nine shilling from Ellen Morris. It seems that Morris had sent her son to the Vine Inn, Lower Darwen for some rum. The boy had given a sovereign but he only fetched sixpence change. It transpired that the change had been put on a table where Ned was sitting and then missed. Later when the stove in the room was being cleaned the change was found in the ashes. Ned and Townend were committed to trial at the Preston Sessions. Although the case at the sessions is mentioned, no verdict is given.

That seems to be the last time Blind Ned is mentioned in the papers other than for his obituary 30 years later. Edward Sharples died on Thursday the 14th February 1895, aged seventy-two; he was buried at St. Pauls Hoddlesden. His obituary reads:

Sudden Death of a Pickup Bank Farmer: At six o’clock on Thursday morning, “Edward Sharples, farmer, of Hole House Farm, Yate and Pickup Bank, was found dead in bed by his wife. The deceased, who was 72 years of age, had been in failing health for a considerable time.”

His wife lived on for another six years dying, aged seventy-eight, at Rawtenstall.

Although Blind Ned was not everything the article made him out to be he must still have been a remarkable man.

Article from the "Blackburn Times" May 14th 1910

Flying Machine At Feniscowles

Germans Working Man's Invention

By Ranger

About five years ago when Santos Dumont was creating sensation after sensation with his flying experiments, an ordinary working man, then residing in Blackburn, occupied his spare time dreaming of the question of the conquest of the air. Week after week and month after month he gave the subject his most serious thought, and that he was not, a mere visionary was evidenced by the schemes he devised and the plans he drafted. For want of time and lack of plant, however, the transforming of ideas into practical form remained in abeyance, and, it was not until the exploits of the Wright Brothers, Bleriot, Rougier, Farman, Paulhan, and Latham electrified the world, that the imagination of this working man was again stirred with ambition and with a desire to construct a machine of his own. As yet his ambition to fly has not been realised; but at least, he has produced a machine which is now waiting to be put to a practical test. The inventor is Augustus (Alfred) Gerhmann, of Laurel Bank Terrace, Feniscowles. He is employed as a joiner at the Star Paper Mill, and it is due to the kindness and consideration of Mr. J. R. Jepson and his Co- directors that Gerhmann, who is of German extraction, and was once a ships carpenter, has been given the opportunity of developing his ideas.

The whole of the machine has been built at the mill—a joiner's shop has now been requisitioned as the hanger. The Director as well as several experts who have seen the machine are impressed with it, and in the quiet little village of Feniscowles to say nothing of Withnell the man and his machine are the one topic of discussion. But Gerhman, tall broad and muscular is of a reserved disposition, and in conversation, whilst brim-full of hope as to the ultimate success of his invention, he expressed a hope that no fuss should be made until he had thoroughly proved the merits of his “Flying Fish" as he affectionately calls his machine. It is indeed, of imposing build, looking in the sun, with the shafts of light playing on its huge wings, like some prehistoric bird preparing for flight. The planes—one prefers to call them wings—are very graceful, with the natural curve of a hovering bird. They resemble in no small degree the wings of the gliding machine built by Lilienthal, also a German, who is regarded as the Father of modern flying, and who, unfortunately, sacrificed his life in attempting to solve the problem of aerial navigation. They measure 24 feet across and on the frame, made of oak, ash and spruce embody 36 square feet of fabric. When extended there is not a crease to mare their beauty, so perfect is every detail of their fitting. And, at this point one my mention a striking feature of their construction. By the removal of a couple of bolts the wings close, just like a bird's, and the whole machine can be wheeled through and aperture 3'-6" wide. They modelled after the wings of a flying fish. As Gerhmann said, referring to this particular denizen of the ocean, the flight of the fish is due to the impetus of the leap from the water, and is, apparently not assisted by any movement of the fins, the wings always remaining stationary. If the rigid wing of a fish can so catch the air currents as to enable flight not mere downward gliding so, argues the German, can similar wings assisted by power, make flight more easy. Theoretically, at all events, the proposition seems sound. Behind these things are the elevating plane, which, as required, can be raised or lowered by 3'-6" by simply pressing a lever attached to the right-hand mainstay; whilst the rudder is worked by turning the handlebars of the cycle. In the illustration are shown above the planes two upright sticks, with a crosspiece. On these stretching towards the back have been fixed some additional 29 square feet of fabric, which, of course, give the machine a greater lifting capacity to the total extent of about 500lbs. As the whole machine only weighs 100lbs, there is a wide margin, even with Gerhmann mounted to enable it to rise. The whole is mounted on a lady's bicycle. In America there is a somewhat similar machine in Rickman's Helicopter the driving power being supplied by a tandem cycle; but the comparison can be taken no further owing to the utterly different construction of the other vital parts. The planes elevator and rudder—essentially the vital parts—have been mounted on a bicycle solely for the purpose of experiment. When once these are deemed satisfactory a different body will be applied, with strong motor power. But even with self-propulsion, Gerhmann is confident of being able to fly. The cycle gear has a chain running round it on to two bevel wheels of 6" and 3" diameter respectively, which work direct on the propeller shaft. Each revolution of the pedal means six revolutions of the propellers—made of zinc, each blade being 4'-6" by 1'-4"—And, it is estimated they will revolve over 300 times per minute. What assistance Gerhmann's fellow workers can render they give willingly. Last Saturday, for instance, they helped him take the machine to a certain district, and, through the heavy wind, eight muscular men were sorely tried in holding it down. As any attempt to fly would have been attended with grave risk, Gerhmann was dissuaded from carrying out any experiments. This weekend, however, if the additional plane has been finished and the conditions are favourable he intends to endeavour to make his first flight.

Augustus (Alfred) Gerhmann Standing at

The Wing of His Plane

Augustus (Alfred) Gerhmann was born in Germany in 1864. The 1911 census shows him to be living at Laurel Bank Terrace, Feniscowles. He married Caroline Hitchings at Swansea in 1893 and they had 5 Children. He died sometime in the September quarter, that is July, August or September 1911. The article says he was to test his plane the week after it was written but I can find no indication that he ever did.

Recently this next article was sent to us by Ken Brooks, now living in the USA. It is from a local history column printed in the Lancashire Evening Telegraph, now the Lancashire Telegraph, by Eric Leaver in 1989 entitled; “Pedalling to the Skies" and is an up date of the article above.

Pedalling to the Skies

An Article from the Lancashire Evening Telegraph

By Eric Leaver

Date 1989

My appeal for information about Blackburn's early aviation history stirred memories for reader Fred Hodkinson, of Bank Hey Lane South.

As a boy, he saw both the pedal-powered machine made at Star paper Mill Feniscowles, by works joiner Alfred Gerhmann and the military airship which made a forced landing near Feniscowles during the First World War

Fred, who is 83, says attempts were made to fly the first aircraft at Mason's Farm, near Stanworth, but the day he went there as a five-year old, the machine—called the flying fish—failed to get off the ground.

“My Father was a close friend of Alf Gerhmann and I went with to the sloping field. The machine was built round Alf's wife bicycle and the wings folded up. The pedals turned the propeller," he tells me.

“Alf set of down the hill pedalling furiously and with my dad holding on to one of the wings. Unfortunately the machine didn't get up enough speed to take off.

“Alf later sold the plane to a travelling fair and it was exhibited all over the Country."

Gerhmann—a German-born ships carpenter who jumped ship in England—was skilled woodworker who made violins and also doll's houses for Feniscowles School,

Fred also recalls the morning he and the other boys from Feniscowles heard that an airship had come down on Stanworth hill and ran about a mile-and-a-half over the fields to see it.

“We were late for school and the master. Mr. Yates wanted to know where we had been. Instead of being punished, we were taken back to the scene and helped drive the gas out of the envelope by walking on it. Afterwards the empty fabric was folded up and carted away."

One of the Gerhmann's granddaughters, Mrs. Joan Marsden, of Livesey Branch Road, tells me she has always believed that the aeroplane did take off. My Grandfather couldn't afford an engine but my mother believes that he attached his plane to a steam engine and it was towed into the air," she says.

Alfred Gerhmann

If anyone has further information about this man please contact Cottontown

Carl Kisielowski (1827-1914), Refugee and Grocer

Image from The Blackburn Times, March 7th, 1914

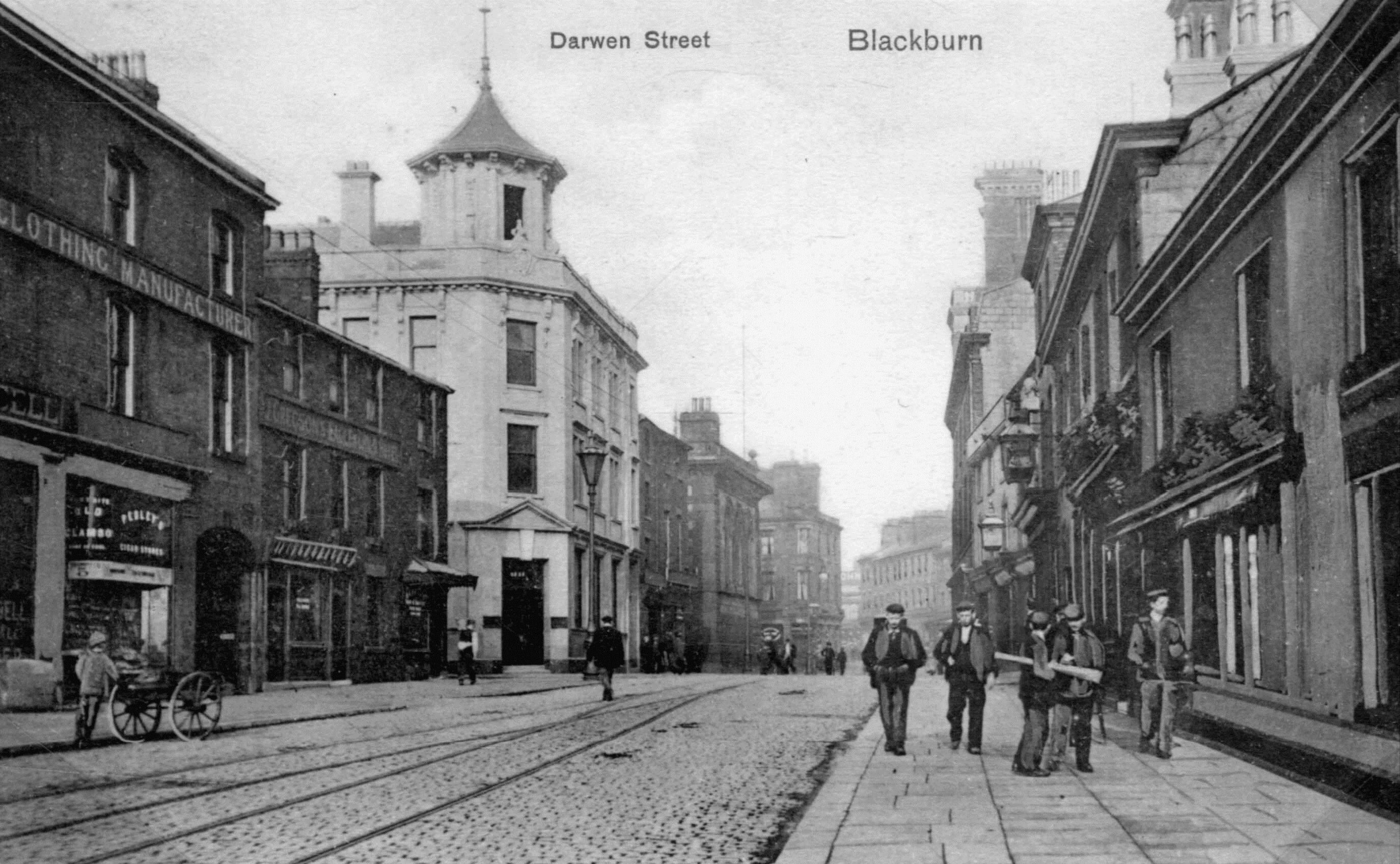

While checking the 1901 Census records for Darwen Street in Blackburn to confirm that the photograph below showed the Eagle and Child hotel, I noticed that the next listing was for Carl Kisielowski, a 73-year-old grocer whose birth place was given as Poland.

The Eagle & Child, Darwen Street, to the right of the "Clothing Manufacturer" on the left hand side of the street.

As the area covered by modern-day Poland was contended by Russia, Austria and Prussia during the 1820s, when Kisielowski was born, and, as the late 1840s, when he would have been a young man, was a time of uprisings and revolutions in many parts of Europe, I felt that Kisielowski must have a story. My hunch appeared to be confirmed when I found the following brief obituary in The Yorkshire Evening Post from 7 March 1914. The author of the obituary was more interested in the claim that Kisielowski had introduced cigarette smoking to the industrial north, but my interest was in the brief mention that he had been sent to Constantinople (modern Istanbul) after 'the Polish insurrection'. No dates were given but further research revealed that Kisielowski had been one of over a thousand Hungarian and Polish troops on Turkish territory after the failed Hungarian uprising in 1848/9 of whom 261 arrived, as refugees, in Liverpool at the beginning of March 1851. Further research revealed a story of how working-class organisations supported these refugees, with little assistance from the government or the middle classes, helping them to settle and to find work throughout Britain. It was through such a network that Kisielowski came to East Lancashire becoming a grocer, first in Lowerhouse, near Burnley, then Blackburn. Kisielowski's life took him from the revolutions and wars in central Europe in the 1840s to the settled life of respected grocer and family man in East Lancashire.

The obituary in the Blackburn Times on 7 March 1914 provided more details of Kisielowski's origins. According to this account, he was born on 7 November 1827 near to Warsaw in Poland. His father was a minor nobleman and landowner, Count Carl von Kisielowski. Kisielowski's father was probably a landowner but other evidence raises doubts about this account. In the 1911 Census, Kisielowski's place of birth was recorded as Galicia, Austria. Today, Galicia is part of southern Poland bordering the Czech Republic and Slovakia with Krakow being the region's major city. In the 1820s, at the time of Kisielowski's birth, Krakow and part of Galicia were part of the Republic of Krakow, which had been created in 1815. The confusion in the Blackburn Times' obituary could have been because, before 1815, Krakow had been part of the Duchy of Warsaw, which had been divided between Russia, Austria and Prussia at the Congress of Vienna in 1815, after the defeat of Napoleon at Waterloo. The only evidence of Kisielowski's father's status is the record of his marriage in 1856 at St. John's, Manchester. His father was recorded as Phoenix Kisielowski, with his first name probably being a corruption of Felix. This is likely because Kisielowski's eldest son was named Felix. Kisielowski's father's occupation was given as 'gentleman', which, in the context of early nineteenth-century Central Europe, probably meant he was a landowner with authority over his serfs. In general, the Blackburn Times' obituary was correct about Kisielowski's family background, he was from minor landowners in Central Europe, but incorrect about his place of birth, he was born in, or near, Krakow, not Warsaw. This latter point is important in explaining how he became a refugee to Britain.

The Blackburn Times, also, gave a brief account of Kisielowski's early life and how he came to be in Constantinople, but gave no details of his involvement in combat. According to the Blackburn Times, Kisielowski, as a youth, attended a military school but, when an insurrection broke out, he escaped then joined a 'native regiment'. He became part of a military campaign until he became a refugee and, with others, travelled to Constantinople. After the insurrection, his father's lands were confiscated. The insurrection, to which the Blackburn Times alluded, was probably the Krakow Uprising of 1846. The Krakow Uprising, or Revolution, began on 19 February 1846 with a rebellion led by landowners in Galicia, of whom Kisielowski's father was probably one. On 21 February the Poles clashed with Austrian forces in Krakow. The Uprising, however, ended after fierce and brutal opposition from the local peasants. On 4 March, Krakow surrendered, then on 16 November, Krakow was incorporated into the Austrian Empire. Nothing is known of the fate of Kisielowski's father, but Carl was landless and had been part failed uprising against the Austrian Empire. Kisielowski escaped to continue the fight for the Polish cause in other parts of Central Europe.

'The Hungarian Refugees', as they were called, arrived in Liverpool on 4 March 1851. The Liverpool Mercury, in the issue published on 7 March, provided more details of how Kisielowski and his fellow refugees came to be in Constantinople. After the failed Krakow Uprising, Kisielowski, along with others who escaped, joined a Polish legion, under the command of General Joseph Wysocki. The legion fought on behalf of the Hungarian cause against the Austrian and Russians. After the defeat of the Hungarian forces in August 1849, by a combination of Austrian and Russian armies, the Hungarians surrendered to the Russians. Wysocki's legion retreated onto Turkish territory where 1034 were confined in the fortified town of Shumla (the modern city of Shumen in Bulgaria). Between the time of their retreat to Shumla and leaving Constantinople in January 1851, the refugees from the Polish legion reduced to 233. Some of the original legion accepted offers of assisted passage to the United States, others went to London as refugees, while some surrendered to the Austrians and Russians, after which they were either forced to join the Austrian army or sentenced to exile in the Caucasus or Siberia. Those who remained in Shumla suffered poverty and persecution but continued to support each other in their determination to be ready to return Central Europe to fight for the Polish cause. Eventually, after pressure from the Russians and the Austrians on the Turkish government, they were forced to leave. During his time in Turkey, Kisielowski may have learnt how to make cigarettes to earn money to survive, but what is certain is that he was involved in an uprising, fought for the Hungarian cause, fled to Turkey and suffered poverty and persecution for over a year.

Sometime during the end of 1850 and the beginning of 1851, the refugees were moved from Shumla to Constantinople. On 22 January 1851, Kisielowski was one of 261 refugees who left Constantinople aboard a Sardinian merchant ship, the Aspia, funded by the Turkish government. The refugees consisted of 247 Poles, 9 Hungarians, 3 Germans, a Bohemian and an Italian. They arrived in Liverpool on 4 March. They were accommodated in an Emigrants' Home, Moorfields, but, as the British government's plan was to send the refugees to the United States, expenses were only provided for three days. On 8 March 1851, the refugees issued a declaration that they resolved to stay in England 'to remain faithful to our duties towards our fatherland'. On 12 March, the refugees were evicted from the Emigrants' House. After initially being welcomed as freedom fighters, criticism of their actions began, and questions raised about their motives. For example, a letter published in the Liverpool Mail on 15 March raised questions about the refugees' motives:

It is strange that all foreign rebels who have fought, or who professed to have fought, “in the cause of freedom," for “Fatherland," and all such humbug, imagine that if they can escape to this country they will be received with open arms, have purses flung into their red caps, palaces to live in, that all men shall welcome them, all women adore them.

The correspondent also declaimed that they would be 'sent to America to work – they come here to fight or beg'. An editorial in the same issue of the Liverpool Mail continued in a similar vein accusing the refugees of begging but also questioning them for alleged republicanism, which was anathema to Englishmen, and implying they were potential enemies of Britain because of their desire for independent Poland and Hungary was a fight against Britain's allies. W. J. Linton, an engraver and radical political activist, in his autobiography, Memories, remembered being 'ashamed of the influential “Liberals" of Liverpool and ashamed … of the then “liberal" government of England'. Linton described how Liverpool tradesmen and the working class began to come to the rescue of the refugees. Peter Stuart, a Liverpool cooper, arranged for the refugees to sleep in an unused soap factory. An unnamed friend of Linton provided straw for bedding while local people brought water. Stuart's help continued when he gave the refugees £50 and vegetables. The refugees had a supply of ships' biscuits from their voyage, but Linton expressed disgust that the customs officers took 10 per cent of the biscuits as duty before releasing them to the refugees. On 10 March, a meeting was held at the Brunswick Hotel at which a committee was formed to raise funds for the immediate support of the refugees. A concert was organised for 2 April to raise further funds. By such means, the immediate needs of the refugees received attention, but they needed more than food and shelter.

If the refugees were to stay in Britain, they needed not only work but also assistance in learning English; none of the refugees spoke English. The Committee of Operatives for the Relief of Polish Refugees was formed with William Costine, a cabinet-maker, as president, and James Spurr, a watch-dial maker, as treasurer. This was the start of what John Belchem, in his 2002 article published in Northern History, described as 'an inter-locking network of committees centred on Liverpool'. In a letter published in the Leeds Times, and other newspapers nationally in late March and early April 1851, Costine and Spurr appealed for to 'fellow-workmen' to help the refugees become citizens by finding the refugees employment so that they could resist 'the coercion of starvation'. They represented the refugees as 'noble-minded and chivalrous men who had sacrificed fortune, liberty, home and friends in vindication of those great principles of constitutional liberty, so dear to the homes and hearts of Englishmen'. Not only were these men noble-minded but also many belonged to the working classes. Costine and Spurr provided a list of trades, such as joiners and smiths, possessed by the refugees then claimed they were 'willing to become fellow-workers with friends of freedom throughout the world'. Through such appeals a network of committees was created throughout the industrial north based on radical and Chartist groups. Chartists had been prominent in working-class politics since 1838 campaigning, amongst other things, for votes for all men (not women). After the failed petition to parliament in 1848, the Chartists had become a more working-class organisation. The Chartists published a specialist newspaper, the Refugee Circular, which became a sort of labour exchange as well as recording achievements of the refugees. Through this network, the refugees were dispersed around the country through radicals, including Chartists, who could offer employment and support, not on skills and the demands of the labour market.

Through this network Kisielowski came to become a grocer in Burnley, although the Blackburn Times obituary claimed that this was not the original trade for which he was intended. According to the Blackburn Times, Kisielowski moved to Padiham to train as a cabinet-maker. In Belchem's analysis of the dispersal of the refugees and their trades, drawn from the Refugee Circular, by the middle of August 1851 seven refugees had moved to Padiham. Of these seven, three were tailors, two joiners and one was a cabinet maker. The cabinet-maker could be Kisielowski but there is no evidence to support this. However, according to the Blackburn Times, Kisielowski was not suited to that trade and moved to the Co-operative Society to train as a grocer. There is a problem with this account. The Co-operative Society, as it is known today, was not founded until 1844 in Rochdale and in the early 1850s Co-operative stores existed in only Leigh, Heywood and Oldham. However, there is a possibility that there was a co-operative in Padiham in 1851, when it is probable that Kisielowski arrived. The Preston Chronicle, in its 13 December issue, carried an account of a co-operative tea party in Padiham. That account stated that the co-operative had been formed in November 1848 and included a store for the sale of provisions and clothing. This was a venture that failed, which is why it does not feature in the history of the Co-operative Society, but it could have been Kisielowski's route into the grocery trade. The obituary of Michael Servetus Holland, published in the Burnley Express and Advertiser on 15 December 1900, offered another path for Kisielowski into East Lancashire and the grocery trade. Holland's obituary claimed that he and his wife had aided the refugee Kisielowski. The links surrounding both Holland's and Kisielowski's marriages provide definite evidence of the network of support with which both Kisielowski and Holland were involved. At the beginning of 1856, Holland married Sarah Rushworth in Padiham, then, in October of the same year, Kisielowski married Sarah's younger sister, Nancy, not in Padiham but in Manchester. Holland and the Rushworth sisters had grown up living on the same street in Padiham. Holland's father was a grocer, but his son had trained as a printer before taking on a newsagent's shop in Padiham. The parish register's record of Kisielowski's marriage provides evidence of the network with which he found support. At the time of his marriage Kisielowski was staying in a house near Strangeways prison. His bride-to-be was staying at 1 Bridge Street in Deansgate in Manchester. This was the home and shop of the radical bookseller, James Renshaw Cooper. Cooper's daughter, Martha Grundy Cooper, was a witness to Kisielowski's wedding and, later, she married the other witness, a fellow Polish refugee, Albert Zamorsky. Cooper was actively involved in the campaign to support the refugees. The Northern Star, in its 5 April 1851 issue, reported a speech that Cooper gave to a meeting of Chartists in Manchester requesting help for the refugees. Cooper not only campaigned but was practically involved; on 9 August 1851, the Manchester Times published a letter from Thomas Hayes, Secretary of the Miles Platting Committee in Aid of the Polish and Hungarian Refugees asking for weekly collections to be paid to Cooper. Although Chartists were active in Padiham in 1851 (the Northern Star published a report of a Chartist meeting in its 26 April issue) no evidence exists linking Holland with the Chartists. How the Hollands and Rushworths came to know Cooper is unknown but the connection is likely to have been through Cooper's trade as a printer or his business as a newsagent. Nevertheless, Kisielowski and Nancy Rushworth's marriage record provides evidence of Kisielowski's link to the Chartist support network.

How Kisielowski entered the grocery trade is unclear but it is clear that he became a grocer and he ran grocery shops in East Lancashire for over 50 years. By 1861, Kisielowski had a grocer's shop in Lowerhouse, Burnley. There he and his wife ran a business and raised a family until sometime in the late 1870s when they moved to Blackburn, taking over Higham's grocers and wholesale business at 26, Darwen Street.

Kisielowski's shop, Darwen Street, is the last shop on the left

He continued there until after his wife's death in 1905. He died at his daughter-in-law's house in Blackpool in 1914. No evidence exists of Kisielowski having involvement with anything related to the Polish cause, after his arrival in Britain, and after being active in Liberal politics in Burnley during the 1860s (he was a Liberal committee member for Lowerhouse in the 1868 general election, listed in the Burnley Gazette on 14 November 1868) he ceased to be politically active. He appears to have settled down to running a business and raising a family with his wife. After moving to Blackburn his eldest son, Felix, became a grocer in his own right, his only daughter, Eleanora, married Henry Woods, a coal agent, his next son, John Thaddeus, was an agent and local sportsman, playing football for Blackburn Olympic and Witton before doing what his father resisted fifty years earlier, emigrating to the United States in 1907, and his youngest son, Victor Menotti, was a Blackburn school inspector and popular comedian in the North West of England. Kisielowski had a quiet and respectable life, not that of a dangerous, revolutionary firebrand as feared by the respectable classes of Liverpool in 1851. Kisielowski's only claim to fame was that he introduced cigarette smoking to industrial Lancashire.

Kisielowski's story has resonance today. Kisielowski, the son of a landowner, arrived in Britain as a refugee from revolutions and wars in Central Europe. He, and his fellow refugees, were abandoned by the government and represented as dangerous republicans and a threat to British values. They were also portrayed as enemies of our allies after fighting Russia and Prussia. But, through the support of a network of tradespeople and the working-classes, Kisielowski, and some of the other refugees, settled in Britain and became part of British society with the fears that they would undermining British society being found groundless. Kisielowski's only threat was that of introducing cigarette smoking to the industrial north!

Addendum

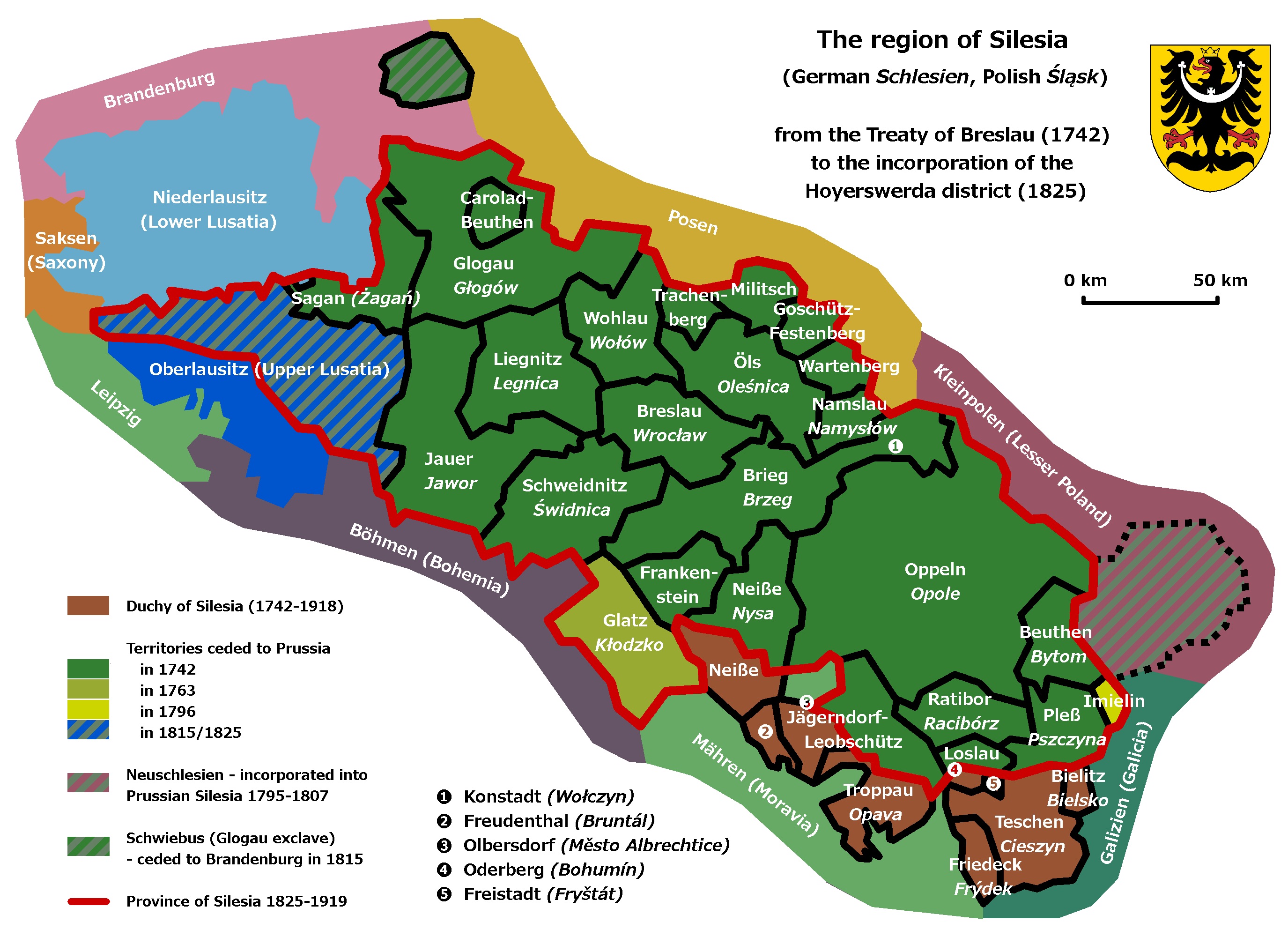

Further research has revealed that Kisielowski was from an old and noble family, not from Warsaw, nor Galicia but Silesia. The family's origins place them at the heart of geopolitical, cultural and religious complexities affecting Central Europe. Some details regarding two of Kisielowski's brothers provides evidence of how this myriad of complexities extended into the family; both brothers served the Austrian empire which Carl, on the other hand, had fought against as a young man.

In its obituary, the Blackburn Times claimed that Kisielowski's father was Count Carl von Kisielowski, and, that the family had a crest that was still in existence at the beginning of the twentieth century. Siebermacher's book of German heraldry, Grosses und Allgemeines Wappenbuch, published in Nuremburg in 1883, showed that the family had not one crest but two. These are shown below.

The

crests are from J. Siebermacher, Grosses und Allgemeines Wappenbuch (Nürnberg,

1883), table 17.

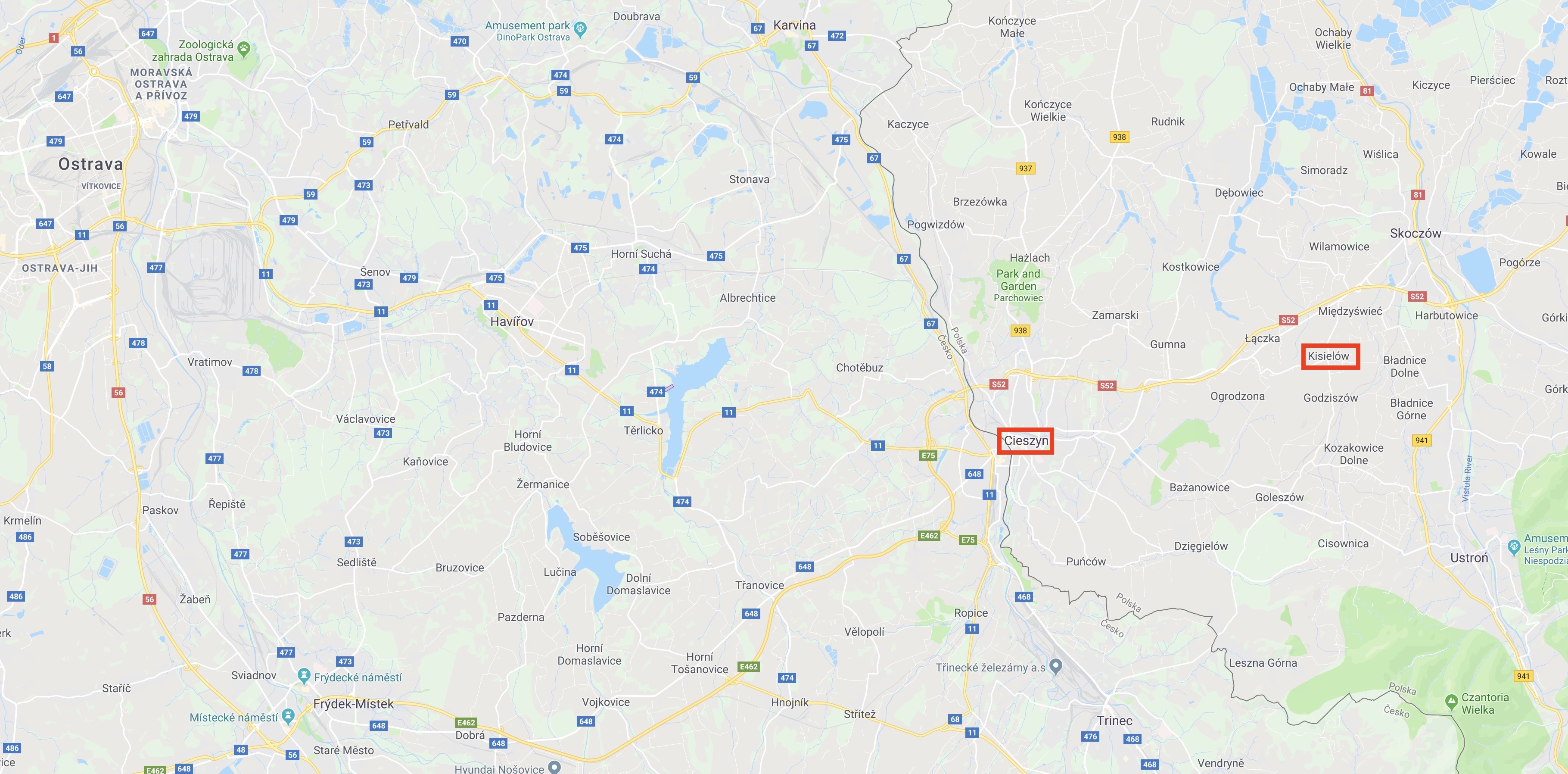

Siebermacher's book and Gottlieb Biermann's history of the Duchy of Teschen, Geschichte des Herzogthums Teschen, published in Teschen (modern day Ciesyn) in 1894, provided some genealogical background. During the fifteenth century a Johann, or Jan, was granted by the Duke of Teschen the right to bear the name of the village of Kisielow as the family name. The Duchy of Teschen was in Upper Silesia and, in the fifteenth century, was a fiefdom of Bohemia but, as Teschen had been part of the medieval Kingdom of Poland, it retained the Polish forms of coat of arms, szeliga and leliwa, the latter form of which remains in use by some Polish families today. Kisielow is located about six miles due east of Ciesyn and about 30 miles from Ostrava in the Czech Republic and 90 miles from the Polish city of Krakow (see maps below).

Map (above) of Czech Republic and Poland showing the location of Kisielow is from Google Maps.

Map of Silesia: Wim Bosmans - Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=30407826

When the Duchy of Teschen granted the family the right to attach the suffix 'ski' (the equivalent of the German 'von' or the French 'de') they became feudal lords with rights to land, and the serfs who worked the land, in return for service to the duchy. The family was granted one coat of arms in 1539 when it held lands in Kisielow and the nearby village of Nierodzim. In 1661 the Kisielowski estate was recorded as one of the Protestant estates of the Duchy of Teschen but, by 1718, it was listed as a Catholic estate; therefore, it is not clear whether the family was Protestant or Catholic. In 1718 the head of the Kisielowski family, along with others, was granted the position of 'Herren Landstände', which placed the family in the rank of the high nobility. In the eighteenth century 'herr', or lord, was one of the three ranks of the senior nobility, the others being ritter, or knight, and prelate, a representative of the church. The Kisielowskis had possessions in Kisielow, Nierodzim and Seibersdorf, the latter of which has not been identified. 1718 might have been the height of the Kisielowski status because Siebermacher noted that in 1760 the family was no longer recorded as holding these estates and that they no longer retained one of the coats of arms. Although the Kisielowski family was of an established noble line, with three villages under its control, it began to suffer a decline in fortunes in the middle of the eighteenth century. Kisilowski's father may have continued to hold some land when Kisielowski was born and may still have had a title but the family's importance and influence had declined.

If Kisielowski was born in Galicia, as recorded in the British census of 1911, the family had moved from its possessions in Silesia. However, Kisielowski was born in the Austrian empire because, although most of Silesia had been incorporated into Prussia in 1825, the Duchy of Teschen remained part of the Austrian empire, eventually becoming part of the Duchy of Silesia in 1842. If the family had moved the few miles from Teschen in Silesia to Galicia, they would have moved from a predominantly German area to the mainly Polish Kingdom of Galicia and Lodomeria. This mix of cultures, along with the different religious identities, as identified in the Kisielowski family history, are representative of the cultural clashes in the region.

The Kisielowski brothers provide evidence of the different responses to the political and social upheavals in Central Europe in the middle of the nineteenth century. The Blackburn Times referred to Carl as having two brothers, Henry and Joseph. According to the Blackburn Time's account, Henry had joined his brother in exile, working in a printworks in Padiham but left to join Joseph working in the Austrian Foreign Office in Vienna. Research confirms this account to be largely true but there are significant differences. Henry, more correctly Heinrich, was much younger than Carl. In the British Census of 1871, Heinrich's age was recorded as 28, which meant he was born around 1843, whereas Carl was born in 1827. Heinrich was a child during the uprisings between 1846 and 1848 and would only have been five or six when Carl was fighting for an independent Poland. Being so much younger could have meant he had a different sense of national identity from his older brother. Why Heinrich came to England is unknown, as is how long he lived here. In 1871, he was employed as a pattern drawer to a calico printer in Padiham. This was when Carl was still a grocer in Lowerhouse. By 1875, Heinrich had left England and moved to Vienna where he worked with his brother, Joseph, more correctly Josef. Josef's age is not known so it is impossible to speculate about the effect of the revolutions of 1846 to 1848 on him. However, unlike Carl, there is no evidence of him fighting the Austrians, the only evidence is that he served in the Austrian army. If Josef was of a similar age to Carl, he could have fought for Polish independence but, after the revolution was quelled, he could have chosen to join the Austrian army rather than become a refugee like Carl. The only evidence is that Militär-Beitung reported that Josef had been promoted to unterlieutenant in the infantry on 8 August 1863. He served in the infantry until 1866 when the Gemeinde-Zeitung reported Lieutenant Josef Kisielowski had been seriously wounded on 22 July at what was then referred to as the Battle of Pressburg (Bratislava). Later, this became known as the Battle of Blumeau, the final action of the Austro-Prussian war of the summer of 1866. By 1871, Josef was listed in the Kaiserlich-Konigliches Armee-Verornungsblatt as a finance official in the Austrian Reichs-Kriegs-Ministerium, or Ministry of War, in Vienna. By May 1875, Heinrich had joined his brother in the same department in Vienna, according to the Militar-Zeituing. So, by the mid-1870s, two of Carl's brothers had not only not chosen exile but had also chosen to serve the enemy Carl had fought in the late 1840s. In microcosm, this shows how a family, whose cultural origins were Polish, responded differently when national identity became a political issue in the middle of the nineteenth century. Carl had chosen exile and a new life in a new country whereas two of his brothers chose to serve at the heart of the Austrian military empire, the very thing that Carl had fought. The Kisielowski family warrants further study but that would mean accessing records held in Austria and Poland.

Sources

Books and Articles

John Belchem, 'Britishness, Asylum-seekers and the Northern Working Class: 1851', Northern History, Vol. 39 No. 1 (2002), pp. 59-74.

Milosz K. Cybowski, The Polish Question in Briotish Politics and Beyond, 1830-1847, University of Southampton, Faculty of Humanities, PhD Thesis (May 2016).

W. J. Linton, Memories (London, 1895).

Krzysztof Marchlewicz, 'Continuities and Innovations: Polish Emigration after 1849', Exiles from European Revolutions: Refugees in Mid-Victorian England, Sabine Freitag (ed.) (Oxford, 2003), pp. 103-120.

Bernard Porter, The Refugee Question in Mid-Victorian Politics (Cambridge, 1979).

s

Blackburn Standard.

Burnley Gazette.

Leeds Times.

Liverpool Mail.

Liverpool Mercury.

Manchester Times.

Northern Star.

Preston Chronicle.

Yorkshire Evening Post.

Online Resources

Birth, Marriage and Death records, Census Records and Travel and Migration Records accessed via www.findmypast.co.uk.

OnLine Parish Clerks for the County of Lancashire, www.lan-opc.org.uk.

Lancashire BMD, www.lancashirebmd.org.uk.

Researched and written by David Hughes, January 2019.

Further information can be found on the following link: Meeting to welcome Polish and Hugarian Refugees in 1851

back to top

Tommy was born in Blackburn in 1925. He started work as a striker for a blacksmith - Little Peel Engineering on Old Leyland Street and also helped his father on a market stall. Tommy joined the Kings Liverpool Regiment during the second World War and on leaving went to work as a milk delivery man for the old city dairy. He then began rag tatting with an old pram. Tommy's career spanned forty years and had started with a five pound note and a pile of clothes. He had hoped to get a stall on Blackburn outside market in 1954 but initially was unsuccessful however later he was granted an allocation. Eventually he had realised that there was money to be made from the rags and waited outside the rag shops to buy the best stuff from the tatters which he then sold on the market. Tommy had married Mary who washed and mended the clothes whilst he repaired the shoes - they lived on Boxwood Street.. It became his trademark to stitch the shoes together in order to stop the pairs being separated. After a while he opened factories in Clifton Street and Salisbury Street making his own shoes but this failed and he went broke. Another venture was a factory making hair stimulant "Wilgrow" but this business also folded.

Tommy went back to the rag trade selling his goods from two shops one on Whalley Range and one at Larkhill before taking a shop next to the Salvation Army and then taking over the derelict premises on Hart Street which then sold new shoes and the shop at the bottom of Ciceley sold re-conditioned shoes. He opened a shop in Chorley and a warehouse on Stanley Street. His motto was "never to sell cheap shoes but to sell good shoes cheap".

Tommy became a pioneer of Sunday trading and in 1982 was prepared to go to jail for opening on Easter Sunday. To get round the law he started opening as a private club charging a fee of twenty pence to enter and used this money and his own amounting to over £18,000 to purchase a kidney dialysis machine in memory of his mother. Tommy even became a Seventh Day Adventist calling Saturday his Sabboth and then opening on Sunday. Tommy was a Blackburn supporter through and through despite his battles with the council and even saved the pot fair after the site at Ewood had been ruled out. Eventually he had to admit defeat over the high court battle with the council over Sunday trading or risk going bankrupt.

Tommy was a generous man well known for buying drinks in the pubs whih he called cheap advertising. He hosted a huge party at his home for two thousand friends and colleagues who had helped him to get to the top in business - all he asked was for them to buy raffle tickets for charity. The business had proved to be a top attraction in Lancashire with an estimated 1.25 million visitors in 1988. Unfortunately Tommy suffered from poor health from the seventies and in 1977 was rushed to hospital after a heart attack at home so that on doctor's orders in 1986 he sold the business for an undisclosed sum. The warehouse was handed over to his two former managing directors Graham Threlfall and Joan Piper. After selling the shoe business he sold bargain clothes and was given permission to open a night club further down Ciceley. After his wife Mary died he held an auction of the contents of their home which caused a dispute with three of his children.

Tommy retired to the Isle of Man at the age of sixty five with his new wife Linda and he died at the age of eighty three on the 30th. of March 2008.

Most of the above is from articles in the Lancashire Evening Telegraph dated 16th. of October 1972, 30th. of October 1981, 20th. of February 1982, 7th. of September 1983 and 2nd. of April 2008. The Citizen supplement of the 24th. of September 1981 and the Blackburn Mail dated the 18th. of August 1983.

Article compiled by Community History Volunteer, Janet Burke, November 2021

Transcribed From the Blackburn Standard of 24th January 1891

Walking on Darwen Moor, one Sunday afternoon early in November last, in company with my dear old friend, Mr William Thomas Ashton, it was suggested by Mr. Ashton that we should look in upon old Lawrence Kenyon, a singular character known to many of our Darwen readers, who occupies a small tenement, with about half a dozen acres of rough land, at Duckshaw, where a small clough skirted by a foot-road, opens near the summit of the moor on its eastern edge. The house stands in the hollow on the steep bank of the mountain stream, which falls in a picturesque cascade. But Nature’s endearing beauty at this spot is not matched by what remains of construction by the hand of man. Lawrence Kenyon’s solitary abode has a desolate and dilapidated look on its exterior, but that is tidy and decent contrasted with the interior, which is about the most squalid specimen of a “home” I have ever seen in a rural situation in Lancashire. My friend had prepared me to expect to find a particularly filthy and unwholesome sort of den or I might perhaps have recoiled at the threshold. The one living room down stairs looks and smells like a hen-roost, which, in point of fact it is for its human inmate shares it with his poultry, of which he keeps a numerous stock. Floor walls and ceiling are black with dirt. In a rusted tumble-down grate, a small fire is burning, and on the hearth-stone the ashes lie in heaps, the accumulation of weeks. There is no furniture except a couple of stools, a tub, an old box, and some sacking. Some potatoes scattered on the floor in one corner were the only articles of food I noticed. Old “Lol” Kenyon, the tenant is a real hermit, and this wretched hovel is his cell. He has lived by himself for years. He has a wife who however, left him long ago, and never comes near him. They were parted because they couldn’t agree. Incompatible of temper is not confined to married people of a superior grade. It occurs in the lowest stratum of society. “Lol” couldn’t adapt his habits and his humours to the ideas of any female living so he dwells alone and avoids domestic rows. He and his fowl little shanty reminded me of Dicken’s description of “Tommy Tiddlers Ground.” Hermits are not admirable when encountered at close quarters. “Distance lends enchantments.” However, Lawrence Kenyon had manners enough to rise from his stool when Mr. Ashton and I appeared at the open doorway, and to offer the seat to one visitor, and of two men who were “camping” him one vacated the other stool, so that we both were seated during the interview; “Lol” and his mates standing propped against the wall opposite the fire. The Sunday clothes of Lawrence were no variation on his work day garb. They were a suit of corduroys, of considerable age and the worse for wear. His frame is broad set but his garments hung very loose. His trousers, especially, were “a world to wide for his (stout) shanks.” His tailor must have miscalculated the amount of further development “Lol’s” person was capable of at the date when he had his last rig out. Lawrence’s face is the freshest and most healthy-looking feature of his outward semblance; it is full and ruddy; and his blue eyes twinkle at times with native humour. Neglected and lost in dirt though he be, Lawrence is not stupid or stolid. His [face] does not scowl upon you but has an open expression of countenance and an agreeable smile as he answers our questions about his marital father. Lawrence Kenyon was the son of the old Peninsular and Waterloo campaigner whose career I am going to notice, though he bears another surname, having been born out of wedlock. His father subsequently married his mother.

William Whittaker was born, as near as I can calculate, about the year 1788 of 1780. His father then lived at Altham, but removed to Blackburn when William was a child. William Whittaker in his latter days, when the town had become more populous, told his children how he used to “whip crows” (whatever that phase may mean) under Darwen Street Bridge in Blackburn. At the age of sixteen, being a strong well-grown lad, and recruits being much in demand at this time, William Whittaker was taken for a soldier. That would be the year 1895 or there abouts. The war with the French Republic was then proceeding, and the Blackburn lad was speedily sent on Foreign Service. He was in a regiment of Horse Artillery. Information is lacking as to the campaigns he served in for the first ten years or so of his soldiering, but at one period he was on active service in America, and he went through the whole war in Spain and Portugal, under Sir Arthur Wellesley afterwards the Duke of Wellington. That “Peninsular War” as it is designated in British military history commenced in 1808, and ended in 1814. William Whittaker had plenty of Experience of desperate fighting in those years. He was [present with his regiment at many great battles and severe engagements. At the peace in 1814, a number of regiments in Lord Wellington’s army were conveyed to America, the country being at war with the United States. Other regiments were brought to England, and these were shipped to Belgium in the spring of 1815, on Bonaparte’s return from Elba. William Whittaker’s regiment of Horse Artillery was ordered to go and fight again the old enemy, the French. He accompanied it and fought and he fought in the final battle and crowning victory of Waterloo. He saw some bloody work in that tremendous struggle, and whilst defending the guns of his battery repeatedly crossed swords with the French cavalry charging the British lines. Himself a tall, massive, powerful man, Whitaker had not a very high opinion of the physique of the French soldiers. They were, he said, mainly less men than the English, and could not fight so stubbornly because they were not fed as well. I am not certain whether this Blackburn warrior was wounded at Waterloo, but in the course of his long service in the army he was wounded several times, but lost no limbs in consequence of wounds. He used to tell that badly wounded soldiers often thought so little of their legs and arms when set against the prospect of a pension, that they would ask the surgeon who was to amputate a shattered limb to saw it off above the knee or elbow joint because they would thereby be entitled to an additional twopence or threepence a day on their pensions. William Whittaker, after Waterloo marched on with his regiment to Paris. A few months later, the army returned to England and was disbanded. Whittaker was discharged with a pension, having served (his son recollected) 20 years and about 145 days. He came back to Blackburn, and settled in the town where he had been brought up for the remainder of his life. That would be towards the end of 1815 or early 1816.

Whitaker was still a single man when he left the army, being of the age of 36 or 37 years, and I suppose would live in lodgings in Blackburn until he married. He made the acquaintance of a towns-woman, named Betty Kenyon, who lived in Nova Scotia. A soldier’s code of morals, after twenty years campaigning abroad, were none too strict in matters connected with love, courtship and marriage. So, it befell that Betty Kenyon became a mother before she was a lawful wife. She had a male child, who was christened Lawrence, and took his mother’s surname. Lawrence Kenyon of Duckshaw, Darwen, the hermit whose personality and environment I have attempted to describe, is identical with that illegitimate son of Betty Kenyon. He is now within a year or two of seventy years of age. His age he doesn’t seem to be sure of. As to his paternity, there appears to be no question that William Whittaker the pensioned soldier was his father. He owned him by soon after marrying his mother. She subsequently bore five other children. William and Betty Whittaker lived together as man and wife seven or eight years, I think, until the husband’s death. They resided in one of the old cottages at Long Row, near Billinge End. Whittaker did not obtain his Waterloo Medal on his discharge, but the Vicar of Blackburn, The Rev. J. W. Whittaker, who was acquainted with the veteran, wrote to the military authorities on his behalf, and in response to his application the medal was forwarded.

Among William Whitaker’s comrades-in-arms who had survived the wars, there were many, pensioners like himself, who kept up the acquaintance; and some of them occasionally travelled long distances to come and see him. Not so lucky as he had been, a number of these fellows had lost arms or legs from wounds in battle, and his wife, Betty, who no doubt knew that the spending of his scanty stock of money on drink would follow, when she saw one of these maimed heroes approaching the house, would remark “Another owd wingy coming.” Whittaker’s prolonged service in the Horse Artillery had given him an extensive knowledge of horses. He was both an excellent judge of the points of as horse, and a competent farrier. He was frequently sent for to the stables of the Feildens, of Feniscowles, the Hornbys and other neighbouring gentry who kept horses, to pronounce his opinion upon a horse offered for sale before a purchase was decided upon. On one occasion at Feniscowles, Mr. William Feilden (afterwards Sir William) wished old Whittaker to say what he thought of a stylish-looking horse which had been sent on approval. The pensioner suspected that the animal had been fettled for the occasion and directed the man in charge of it to run it backwards and forwards on the carriage-drive. He did so, and Whittaker noticed the horse pulled hard at the halter while running, as if it was trying to get its feet off the drive, and onto the grass at the side of it. He then looked at the horse’s feet, sent for the smith to take off its shoes and took from beneath a quantity of soft material with which the hoof had been padded. This is one of several stories about his father told by old “Lol.” By his neighbours and townsfolk William Whittaker in his later years was generally spoken of as “the Old Pensioner.” He lived to no great age, dying aged 51 about 1830, and was buried in the parish Churchyard.

It is a proof of the fact that few families in this district, containing several sons, did not contribute one or more recruiting to the British Army or navy, during the wars which lasted almost without intermission from 1793 to 1815, that both of the men residents in Darwen, who happened to be in Lawrence Kenyon’s house when Mr. Ashton and I called, and who listened to our questions and his replies had relatives who fought at Waterloo. One of then stated that his uncle Thomas Duckworth, served as a soldier in the army under Wellington and retired with a pension. He returned to Darwen, and died some twenty-five years since aged 70. The other man said that three of his uncles were soldiers. Their names were, respectively, John, James and Joseph Walsh. John Walsh (his height was 5ft 11½ inches) and James Walsh (his height was 6ft 3 inches) were both in the Life Guards, and were killed in battle. The other brother was not so tall in stature his height was 5ft 8 inches, and he was drafted into an infantry regiment. He was not killed, but came home on his discharge, with a pension, and also lived in Darwen. He was either father of grandfather of a man named Walsh who is living at present in Carr Road, Darwen and who works for Mr. Ashton.

W. A, Abram

Biography of William Whittaker and Lawrence Kenyon

If, as Abram says, William Whittaker was born at Altham between 1870 and 1880 then the only birth with that name is as shown below.

Baptism: 18 Jan 1777 St James, Altham, Lancashire, England.

William Whittaker - Son of Betty Whittaker

Abode: Altham

Notes: Base Child

Baptised by: R. Longford Curate

Register: Baptisms 1749 - 1788, Page 71, Entry 11

Source: LDS Film 1278856

I found the discharge papers for a William Whittaker, the dates on these are as follows:

Length of Service, 8th May 1809 to 24th January 1816.

He was about 40 years old on Discharge, so using that information, his birth, would agree with that given above, 1776 or 1777. Abram suggests that Whittaker died aged 51 about the year 1830, this again gives a birth date of around 1779, which fits in with the above, and so, William Whitaker could well have been the illegitimate child of Betty Whittaker.

However, I am not convinced that this is the William Whitaker we are looking for. Searching the 1841 census I came across a record giving the information shown below;

William Whittaker 50 hand-loom Weaver

Betty Whittaker 30 Hand-loom Weaver

Lawrence Whittaker 12 Hand-loom Weaver

Robert Whittaker 9

Sophia Whittaker 7

Henry Whittaker 3