The manufacture and development of electronic components was to become of Blackburn's mainstay industries. One of the largest electronics companies was Mullard Limited who were part of the larger company of Philips of Mitcham. They were the first to occupy land on the new Whitebirk Industrial Estate when itn opened in the late 1930s. Mullard had been founded by Mr Stanley Mullard in 1920 and manufactured radio valves. Mr Mullard was considered to be a pioneer in the radio industry and during the war had been involved in the development of military radio communications.

By the end of 1938 Mullard were producing 6,500,000 valves per year and were to later be involved in the manufacture of components for television sets. During World War Two they produced components for military systems and by the 1950s were involved in the manufacture of cathode tubes for television. When the Queen made a tour of Blackburn in 1955, the Mullard plant was one of the places she visited, it was hailed as a beacon of new industry in the Lancashire area. During the 1970s the Mullard plant occupied over 46 acres of land in Blackburn and employed over 5000 people. They were responsible for the manufacture of tens of millions of capacitors, transistors and valves every year. In 1969 they had begun production of components for colour television and production took place at the plant at Little Harwood and at a large site in Simonstone.

Mullard was to move into even more high-tech industries throughout the early 1980s. It was jointly responsible for the development of laser disc technology then known as the Philips Laser Vision Home Entertainment disc, this would later become the CD, CD-rom and DVD technology that we are now so familiar with. The company became internationally renowned, making news in the 1980s because they were exporting components to the technologically advanced Japanese. Mullard components were considered to be of the highest quality, winning a British Quality award in 1987 for its production of top quality components with an ability to produce 'zero defect’ T.V. and video components.

By Rachael Spencer

back to top

Although Blackburn owes its development and prosperity to the cotton trade, engineering was once a major employer in the town, and the industry's products were exported throughout the world. Early nineteenth century machine makers were principally concerned with supplying the textile industry, or in producing goods for domestic use. A particular emphasis on weaving machinery was apparent by the middle of the nineteenth century, and Blackburn iron founders, including Joseph Harrison, William Dickinson, Mark Knowles and Henry Livesey were instrumental in perfecting the power loom. The manufacture of textile plant remained central to engineering well into the twentieth century, although by this time the major companies were heavily involved with exports, in addition to equipping local mills.

The undoubted success story of Blackburn textile engineering during the present century is that of British Northrop, a business which manufactured a staggering number of automatic looms between the 1930's and the late 1950's. Unfortunately this success could not be maintained and in recent years the company has been operating with a much reduced workforce and on a far smaller scale. One consequence of Northrop's spectacular rise was the collapse of the traditional Lancashire loom makers, and today only Henry Livesey Limited remain in production, although they have long since ceased to make power looms. To a certain extent this decline has been offset by the introduction of tufting machinery manufacture, although a number of companies in this field enjoyed only brief years of success. From at least the 1820s Blackburn millwrights produced stationary engines and steam raising plants. Directory evidence suggests that most iron-founders were capable of turning out engines, as well as producing textile plant and items for the domestic market. Increasingly this branch of the trade began to be dominated by three major firms, William Yates & Sons, Clayton, Goodfellow & Company Limited, and Ashton, Frost & Company Limited. Upwards of 90% of all local mills were engined, or re-engined by these companies, and most had boilers made at Canal Foundry.

From about 1860 onwards Blackburn made engines were exported and by the beginning of the new century large numbers of colliery winders, water pumping and textile mill engines were being sent abroad, mainly to India and South Africa. This trade, although reduced after 1920, survived until the outbreak of the Second World War. A wider range of products was offered by the remaining heavy engineers during the post-war years but this was unable to stave off their eventual closure in the 1970s and early 1980s.

Currently a number of small and medium sized specialist engineering firms exist in Blackburn, often in converted buildings, or in custom built industrial units. The three large iron foundries of the town remain underused, or empty, and it seems doubtful that Blackburn, which was made famous by firms such as Yates & Thom and British Northrop, will again see an engineering industry on the scale of the past. The characteristic buildings of the trade are single storey machine and erecting shops covering an extensive ground area. These are often brick built with circular and roundheaded windows placed high in the walls. Wide, tall doorways, to facilitate the despatch of heavy machinery are also evident. Internally the buildings are cast iron or steel framed, with travelling overhead cranes and narrow gauge track set into the floors. Large areas of the roofs are glazed, either in northern light form or with sky-lights. The cupolas and furnaces are amongst the first part of a foundry to vanish after closure, however, moulding shops often survive. These can be distinguished by wooden louvres, for ventilation, set on the apex of the roof. Drawing offices, store rooms and pattern shops were usually housed in multi-storey blocks which often overlooked the machine floor. These design features can be clearly seen in a number of Blackburn examples, particularly at Bank Top and Canal Foundries, and to a lesser extent at Atlas Works and in the oldest Northrop buildings.

By Mike Rothwell

back to top

Engineering works of various sizes have been part of the industrial scene in Blackburn for many years. John Haworth's Borough Wire Works was set up in Mincing Lane in 1835 by Francis Anderton. The company produced wire netting for agricultural purposes, iron wove wire for mining purposes and gauze wire for steam joints, safety lamps, blinds etc. Dish covers, fire-guards, sieves and wire staples were related products.

Thomas Winter and Co had works in Byrom Street and Canterbury Street which were established in 1875 in St. Peter Street. They specialised in brass and copper work of every sort, producing pumps, ginger beer machines, bottling machines, valves of all kinds, water and steam gauges, hydrants and hose couplings.

Clayton, Goodfellow and Co were established at the Atlas Works in Darwen Street in 1850. They had early success with a special piston for steam engines, but realised the need to diversify. They began producing complete engines and then to act as contractors for complete factories. In 1872 Williamson's of Lancaster began producing cork linoleum and Clayton Goodfellows were contracted to supply the machinery. Lino was such a success that 30 fitters from Clayton Goodfellows were permanently based in Lancaster. There was so much work, so much overtime, that it is said the men devised a scheme for getting a day off. They threw a hat in the air, if it stayed there, they went back to work, if it came down they had a day off.

During the First World War Clayton Goodfellows turned to war work producing gun barrels, torpedo tubes and shells, hundreds of thousands of shells for 18 and 60 pound guns, shells that were to tear up the fields and the fighting men of France. In the Second World War they made the winching gear for the Mulberry Harbour, essential to the Normandy landings.

back to top

Technological developments have always been at the forefront locally since the days of James Hargreaves. Skilled hands and quick, inventive brains, have combined to produce countless innovations and improvements. The need for technical education was recognised back in the 1880s and the Technical School was opened in Blackburn in 1891.

Blackburn exported this technical know-how all over the world, ironically leading to the demise of its own major industry. It was this tradition though, which was to form the basis of its regeneration. This is clearly demonstrated in the case of the British Northrop Loom Co. Limited. Henry Livesey's textile machinery company worked from the Greenbank Works. They built the first model "T" looms for the fledgling British Northrop Loom Co. Limited. Once the business was growing British Northrop built their own factory on Moss Street and in 1929 they built a larger factory at the end of Moss Street. Makers of Northrop Looms which were exported overseas, they supplied machinery to countries who had previously relied upon the cloth made in Blackburn. Increasingly, they were the owners of up-to-date machinery and methods and their use of the automatic loom far outstripped its use in Blackburn where the Lancashire loom was still prevalent. However, this demand for looms and machinery ensured that their business stayed healthy.

Another step in the regeneration of Blackburn was the building of the industrial estate at Whitebirk in 1938. This was the first of many to come and was the home of Mullard, which became a household name in Blackburn and who made radio valves. They later produced components for aircraft before settling with the manufacture of components for television sets. This locally-produced technology kept many in work.

By Rachael Spencer

back to top

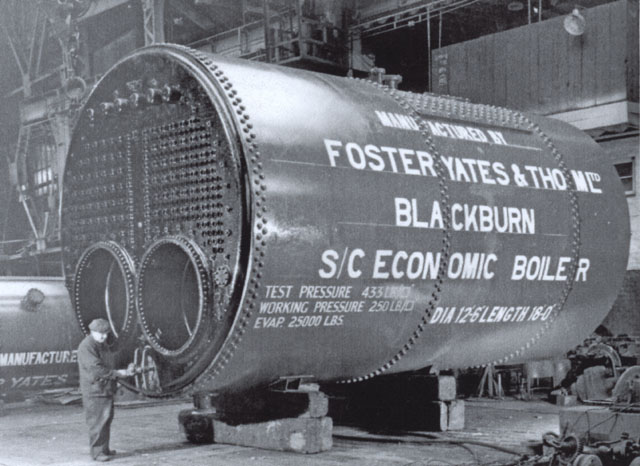

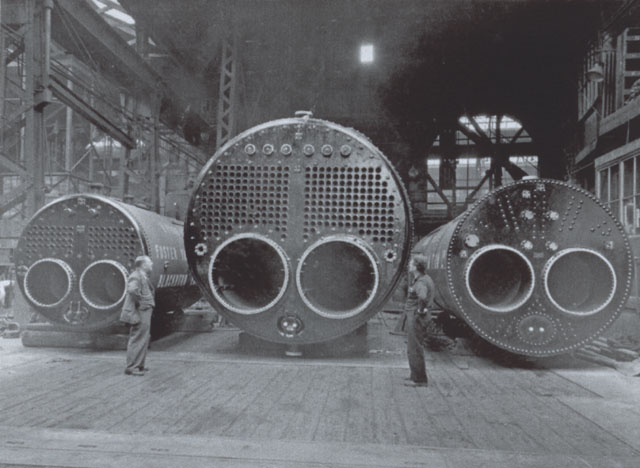

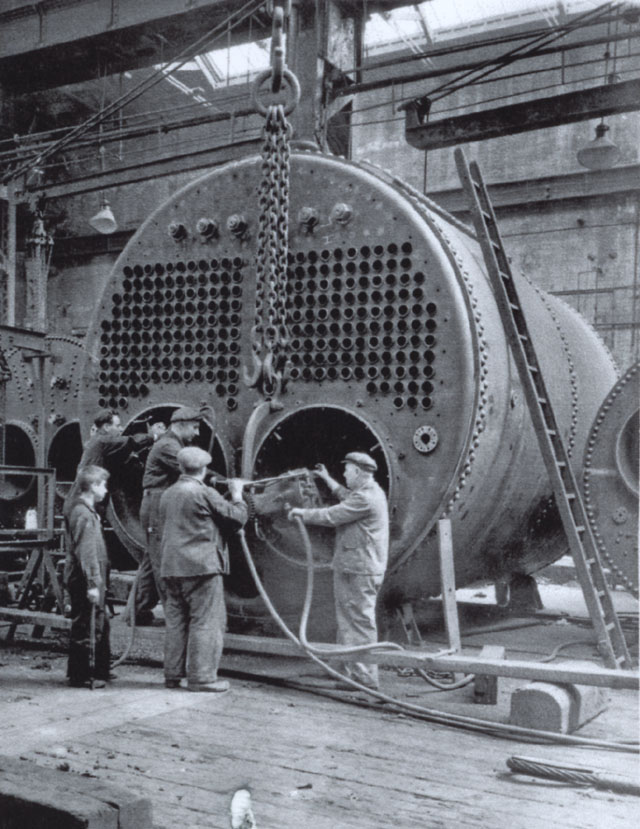

It's almost 40 years since Foster Yates and Thom went out of business. Once their boilers and steam engines were sent all over the world. These photographs have been copied and passed on to Cottontown by Jim Halsall. They were loaned to him by Gordon Hunter, a former employee.

Jimmy Barnes, boilershop foreman on left, next to him Billy Allan, boiler site fitting foreman.

Danny Shaw demonstrating how to tighten manhole cover.

Two self-contained Economic boilers with a Lancashire boiler on the right. Arthur Hulme,

boilershop manager is on the right, foreman Jimmy Barnes on left.

Boilers at railway sidings in Blackburn.

Rivets being put in place hydraulically. Driller is Harry Valentine with rivetters Danny Shaw and brothers Frank and Harry Woods.

back to top

Peter Harrison, a former director of Clayton Goodfellow has written a short history of the company who were based at Atlas Ironworks, Park Road, Blackburn.

This firm was formed as a partnership in 1857; became a company in 1897; ceased trading circa 1983; finally being dissolved in 1996.

In researching the early partners and directors of the company, there are some facts, some assumptions and some probablilities.

The facts are that Jacob Goodfellow who founded the company was an engineer; was a brother to and an associate of Benjamin Goodfellow, who in turn ran a well known engineering company in Hyde. His wife was Betty Sourbutts, the sister of Alice, wife of William Harrison (mentioned later). His co-founder William Clayton, was a hatter from Denton, obviously not an engineer. He was well known within the Harrison family as the producer of the required funds for setting up the business. This is an assumption.

Jacob’s raison d’etre was that he had invented a special piston for steam engines, which he wished to manufacture using his own company. John Harrison (1839-1923) the first chairman of the incorporated company was the nephew of Jacob Goodfellow and the son of William Harrison who was also a hatter from Denton near Hyde. William Harrison was the same age, had the same profession in a neighbouring town as William Clayton. Here we have a probability in that they were at the very least, known to each other.

Richard Henry Clayton, William Clayton's nephew, was a cashier which was presumably his role in the company. His brother was Thomas Clayton who was married to Betsy Goodfellow, a distant member of the Goodfellow family.

William Loynd was an engineer, who was a partner, then a director and who with his wife Ellen, both became initial share holders in Clayton and Goodfellow. He came from Great Harwood. Prior to joining C and G he was in partnership with Henry Turner Sourbutts in Hyde, making steam taps and lubricators. Ellen came from Godley near Hyde, thus we have the possibility that they met whilst William was working at Goodfellows of Hyde.

It seems highly probable that all the founders of Clayton Goodfellow and Co were either family members or prior associates of each other.

They bought a plot of land in Park Road near the centre of Blackburn where the factory remained for the next 126 years. They chose their location well, as not only were they near the centre of Blackburn, they were in the very heart of the then thriving Lancashire cotton industry, which they were to serve profitably for many years to come.

The manufacture of the pistons and other related parts, with upwards of 10,000 being made, led firstly to the production of entire steam engines along with the enormous cast iron flywheels, up to 30ft in diameter, and necessary drive shafting and to the equipping of complete mills. The labour force built up to 300 during this time and remained so for the rest of the firm’s existence, though there were troughs from time to time when trade was bad.

In due course the original partners retired and among the succeeding partners was John Harrison, the nephew of Jacob Goodfellow, who was the first of 4 generations of Harrisons who became partners/directors of the company, until its sale to Wm Brandt Sons & Co Ltd in 1969. All the existing directors resigned and Brandts elected Messrs. W H N Wilkinson, T R Aldington, C W Heathcote and Sir Christopher Crossley, Bart in their place.

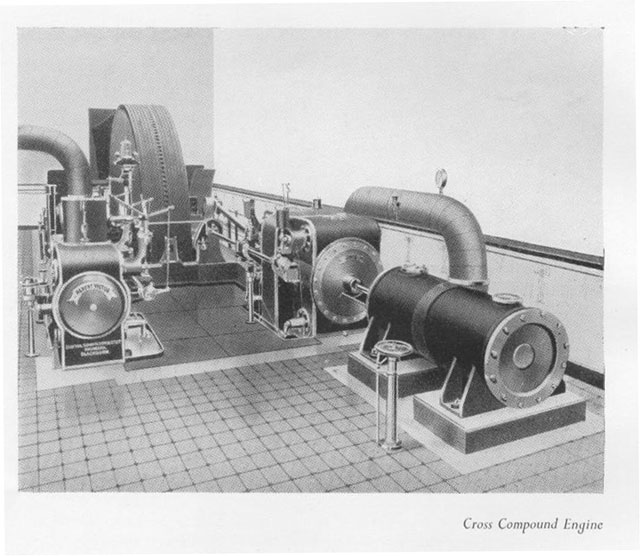

The steam engines which were the mainstay of the output in those days were the Cross Compound Condensing engine, which came in two models: the Horizontal for stationary work and the Vertical for marine applications. The Uniflow was introduced rather too late as the market for steam was dwindling. A Triple Expansion engine was also being developed which would allow the user to bleed off steam for other uses.The company’s steam engines designed and marketed for the cotton industry, were also used for steel rolling mills, winding engines for collieries and for powering Lord Ashton’s Linoleum factory in Lancaster.

However two huge clouds were on the horizon in those days, which were to signal the beginning of the end of the steam engine. The first was the introduction of electric motors, which could be used to drive individual machines or a small group of the; which were more flexible and in the end much cheaper. The second was, of course the gradual removal of the cotton trade from Lancashire to India and countries east.

Prior to the above taking effect however there was the small matter of the World War 1, the like of which had never been seen before. The effect on Clayton and Goodfellow was to stop nearly all normal trade, and because the government had thought that their Royal Ordnance factories could cope with their requirements, few orders were placed with outside contractors.

It was to be nearly 2 years before the deluge arrived, and then the company could not cope with the demand for shells, gun barrels and torpedo tubes etc. Their machinery was not designed for high volume repetition work and by the end of the War many machines were totally worn out, and replacements had to be purchased.

It was quite right that companies should not profit from war work but the fact was that Clayton and Goodfellow survived their war much the poorer.

Peace brought with it a temporary dividend and the factory was busy for the 4 years leading up to the cotton slump when trade all but collapsed; which along with the afore mentioned “electric motors” meant that the firm struggled mightily to keep its doors open.

It was obvious that a living could no longer be made from the cotton industry and new lines had to be found.

Brick making machinery was one of those lines, introduced by Thomas Whittaker. As trade slowly began to improve the demand for house bricks increased. This demand was largely catered for by the Fletton brick, manufactured at London Brick, Marston Valley and Eastwoods amongst others. Fletton clay made cheap bricks because oil in the clay burned, thus needing less fuel in the kilns.

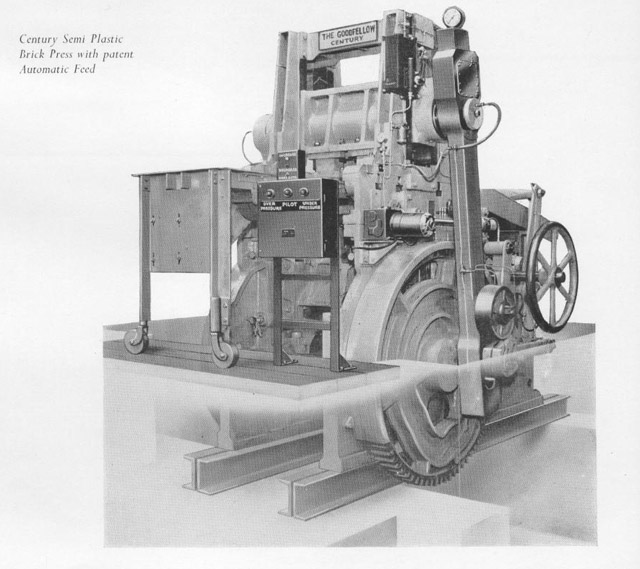

Clayton and Goodfellow made the presses for these mass produced bricks, and there being only one other competitor in the field (Whittakers of Accrington), it was profitable work. These presses: the Goodfellow Junior and the Century press were still being made into the 1970s.

Other items made for the brick industry were extruder mills, which made bricks by extruding clay, the individual bricks being cut off by a wire, and large crushing mills which turned the shale into workable clay.

These same mills were used in the glass industry to crush glass cullet (waste glass) into a form that could be re melted into new glass.

Altogether the 1930s with the slump in the textile industry, the General Strike and the Wall St crash was not a good decade for Clayton and Goodfellow Co Ltd, but it survived in reasonable shape to face the next horror, “World War 2”.

As is well known, World War 2 started with the “phoney war”; this situation being mirrored by hesitant production at Clayton and Goodfellow; but this time the company was eventually asked to produce tank parts, which were much more in tune with their machine capacities; parts being made for the Crusader, Centaur, Covenanter and Churchill tanks.

Parts were also made for many types of gun, including anti aircraft and large naval guns. Flash-tight doors were made for “The Prince of Wales” and “The King George V” battle-ships along with equipment for submarines.

Finally they received a letter of thanks from Field Marshal Viscount Montgomery, for their help in making the winching gear that was used for winding down the legs on the Mulberry harbour; so vital for the “D-Day” landings in France, which heralded the beginning of the end of the War in Europe.

Altogether, everyone worked very hard and for long hours, making the multitude of arms needed for modern warfare; and, as a first in the industry, women were employed as crane drivers, labourers and a few machine operators, doing their bit for the War.

Peace came at last, bringing with it a small lull in work whilst every one took stock and readjusted to the new situation. But by the end of 1946 the works was busy again. Brick machines were still selling in good quantities; some cotton mills were reorganising for electrification and Clayton and Goodfellow got their share. Paint making machines were being made under the name of Smith Blythe Eng Co Ltd. This line too was doing well.

However a new Clayton and Goodfellow was slowly emerging in order to meet the challenges of the post war era. This started with the manufacturing of Ballast cleaning machines and Ballast tamping machines for the Swiss company Matisa Equipment Co Ltd. These were huge machines sold to railways round the world. These machines were self propelled units that travelled on rail tracks. In the case of the ballast cleaner, it had an endless belt that ran under the rails, scooping all the ballast stones up, dropping them on to a vibrating screen, discarding the rubbish and replacing the cleaned ballast under the track. The tamper followed it (or worked independently) tamping the ballast solidly under the rails and sleepers.

This equipment needed a large welding department, so Wellington Mill (a disused cotton spinning mill) was purchased to cater for this requirement. Unfortunately it also signalled the end of the necessity for an iron foundry, which was eventually closed.

During this period of relative prosperity the company reached its’ centenary in 1957, and celebrated it with a grand luncheon held at the Moorcock Inn at Waddington. Amongst the guests were the Mayor and Mayoress of Blackburn, Councillor and Mrs Henshall, along with many of the company's customers and senior members of staff. Hosted by Mr and Mrs William Harrison (chairman) and Mr and Mrs John Harrison (past chairman), the guests numbered 100.

Further contracts were made with Belgian (Vandergeeten) and French (Remy) companies respectively to make bottle fillers and bottle cleaning machines, for the brewing industry; followed by a partnership with a German design company (Loewy) who specialised in steel rolling and coiling machines.

These three European contacts plus a large contract from ROF Barnbow for Centurion tank suspension units kept the plant humming for some 20 odd years.

Unfortunately engineering was in decline both in Blackburn and nationally; times at Clayton and Goodfellow were becoming increasingly hard. Profits were even harder to come by, meaning that the family could no longer sustain the works and so in 1969 the company was sold to the Merchant Bankers Wm Brandt and Co Ltd, who were able to extend its life till 1983. At which time the company ceased to trade.

The life and times of Clayton Goodfellow and Co Ltd, largely mirror the situations of the cotton and the following engineering industries of Blackburn; where, for over 100 years, cotton was king, followed by 20 to 30 years of engineering. Today the town largely relies on service industries.

The factory site was situated in a corner between Park Road and Lower Audley Street, with the main Blackburn railway at its rear. The front entrance for the offices being on Park Road and an entrance directly into the works on Lower Audley Street.

The buildings immediately post World War 2 consisted of 4 main sheds, running parallel to Park Rd; the most easterly being the iron foundry, with 2 furnaces. There was a fitting and assembly shop, at the bottom end of which was a 3 storey building, housing, on the 1st floor a tool room and on the second floor a pattern shop. At the western end (nearest to Park Road) were 2 machine shops. At the Park Road entrance were offices on one side with a smithy on the other.

When the foundry closed, the shed became a fitting shop and the tool room moved to the smithy, which had been closed. The pattern shop moved to Wellington Mill. The vacated floors becoming planning and drawing offices.

Aerial photographs, taken between the wars, show that the middle shop (next to the foundry) did not have a roof. The date of this area being roofed is not known to the writer.