The Struggle for Women's Right to Vote in Blackburn

The women's suffrage movement began in earnest from about 1866 when the first women's suffrage societies were formed in London and Manchester. Their aim was to highlight the issues surrounding women's suffrage and persuade Parliament to give women the vote.

Probably the most fighter for women's rights was Emmeline Pankhurst who was the leader of the Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU), which she founded in 1903. The WSPU was a suffragette organisation, that is, they were militant. They tried to force Parliament to give women the vote through acts of vandalism and violence. There was another large national organisation for women's suffrage called the National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies (NUWSS), which was set up in 1897 by Millicent Fawcett. They were known as the suffragists because, unlike the suffragettes they never resorted to violence to get their way. They campaigned peacefully by making petitions and distributing leaflets to raise awareness of “The Cause". Many of them aimed to prove by logical deduction that women were equally intelligent to men and therefore deserved equal rights in the laws and opportunity to help make those laws.

Blackburn was not without its own suffrage campaigns. Evidence from copies of “The Blackburn Times" from 1901 and early 1914 suggest that Blackburn had active suffragists and suffragettes. Famous suffragist Selina Cooper spoke here at least twice and her “Mill Girls" petition to Parliament almost certainly came here, although no representative from Blackburn went to Parliament to present it.

Lady Norman, who was a bit of a local celebrity, was seen to support the Suffragist Society, the Liberal Women's Suffrage union which wanted more support for Liberal candidates who supported women's suffrage and was founded by her mother Lady Aberconway. This association was to stop women becoming suffragettes by having them pledge to work with and for the Liberal Party and support those Liberal candidates who promised to support women's suffrage.

Lady Norman, who was a bit of a local celebrity, was seen to support the Suffragist Society, the Liberal Women's Suffrage union which wanted more support for Liberal candidates who supported women's suffrage and was founded by her mother Lady Aberconway. This association was to stop women becoming suffragettes by having them pledge to work with and for the Liberal Party and support those Liberal candidates who promised to support women's suffrage.

On Sunday 31st January 1914 at least ten suffragettes got into the Olympia Theatre, (Mecca Bingo Hall), in Blackburn to disrupt a meeting of the Blackburn Independent Labour Party (ILP) where Mr Philip Snowden was speaking. Their arrival had been anticipated and there were guards at the door to stop them getting in. Several suffragettes attempted to get in but many did not. Three suffragettes were removed from the theatre before the speaking started and two more followed them out. One suffragette called out something but it could not be heard on stage. She was forcibly evicted by a steward and another suffragette, who was sitting near her, followed her out. Later Mr Snowden said “I want it clearly understood…." And a suffragette finished his sentence “That women want the vote!" The stewards attempted to evict her by force but, after a brief struggle she walked out followed by another suffragette. Part way through Mr Snowden's speech a young suffragette smartly dressed in black interrupted by shouting “why not give women the vote?". This was followed by a great deal of laughter and no answer. When the steward approached her she got up and walked across the balcony to more laughter. She stopped to survey the audience with scorn and disapproval. She was quickly pushed out of the door. Mr Snowden said nothing about interruptions, just carried on with his speech. His speech did not contain anything on the topic of women's suffrage.

In February of the same year, a suffragette called Gertrude Bentley who lived at 204 Revidge Road received 14 days for imprisonment for “chalking the pavement" and refusing to pay the fine of 10 shillings plus damages. She had written in chalk “W.S.P.U. A mass meeting will take place in Market square at 7.30pm tonight" on the surface of Railway Road. Similar messages were found on the footpaths of the Boulevard, King William Street, Richmond Terrace and other streets around the centre of town. However, it could not be proved that Gertrude Bentley made any of the markings. She said that she was not aware that chalking on pavements was illegal but she was told that ignorance of a law was not a good enough excuse to break it! Gertrude Bentley was the other Blackburn organiser of the WSPU.

In February of the same year, a suffragette called Gertrude Bentley who lived at 204 Revidge Road received 14 days for imprisonment for “chalking the pavement" and refusing to pay the fine of 10 shillings plus damages. She had written in chalk “W.S.P.U. A mass meeting will take place in Market square at 7.30pm tonight" on the surface of Railway Road. Similar messages were found on the footpaths of the Boulevard, King William Street, Richmond Terrace and other streets around the centre of town. However, it could not be proved that Gertrude Bentley made any of the markings. She said that she was not aware that chalking on pavements was illegal but she was told that ignorance of a law was not a good enough excuse to break it! Gertrude Bentley was the other Blackburn organiser of the WSPU.

© People's History Museum - terms and conditions

© People's History Museum - terms and conditions

By far the most interesting and unusual event involving a suffragette in Blackburn was the firing of the cannon in Corporation Park in mid-February, 1914. At about quarter past seven on February Sunday a loud bang was heard throughout Blackburn and even beyond. The house around the park were reported to have been shaken by the blast and the police and fire departments were overflowing with people wanting to know what was going on. Many people thought there must have been an explosion at the Addison Street Gasworks. There was an official statement to the contrary but it was not until Monday morning the truth was discovered. It was obvious that the cannon had been fired as someone had removed several years' worth of stones and gravel from the barrel. Also, the surrounding area was splashed with a yellow substance that indicated that the cannon had not been cleaned properly before use. Experts at the time reckoned that about 11/2 lb of explosive was used, not enough for a proper charge which would have moved the gun but enough to make a loud noise. People who were in the park at the time of the blast saw a flash of light and reckoned it was a lightning bolt. The cannon firing was blamed on suffragettes because on Monday morning a brown paper parcel was found next to the cannon. Inside the parcel was a large piece of calico cloth on which was written in blue pencil:

Wake up, Blackburn!

The Labour Party who claim to stand for

Justice and Freedom

Support a government that Tortures Women

Under the Infamous Cat and Mouse Act.

The Cat and Mouse Act allowed hunger-striking suffragettes to be sent home to regain their strength then be rearrested; this was to make sure that none of them died in prison and gave the cause a martyr. Also, in the package was a copy of the newspaper “The Suffragette" and a book by Christabel Pankhurst (Emmeline's daughter). The “Blackburn Bomber" was never caught. The women's suffrage movement generally ended with the start of World War 1 but because of the courage an and ingenuity women showed when they took up men's work during the war Parliament finally gave house-holding women over 30 years the vote in 1918, and all women over 21 got the vote in 1928, making them equal with men.

By Fiona Smith (Age 16), Head Girl at Beardwood School. This essay was completed during work experience at Blackburn Museum and Library.

back to top

Louisa Entwistle, Blackburn suffragette, was gaoled for her part in a raid on the House of Commons on Wednesday 15th February, 1907. Here, she recounts her experiences to the Blackburn Weekly Telegraph of

9th March, 1907.

Barbara Nightingale has kindly supplied us with this information about her ancestor.

It is said that when Miss Louisa Entwistle the young Blackburn Mill girl who went up to London to fight in the “the battle of the suffragettes," took her stand in the docks at the Westminster Police Court the morning after she and fifty others of her sex made the now famous raid on the House of Commons on the opening day of the present session, somebody in court, struck with her youthful appearance, exclaimed, “Votes for children!". Miss Entwistle pleads guilty to the accusation of youthfulness, for she does not attain her majority until near the end of the present month, but despite this talk with her reveals the fact that she has clear and well-formed ideas on many of the social and political questions of the day, and a strong and burning enthusiasm for the cause she has taken up. She looks forward to with a bright hope to the time when women may take their part with men in the endeavour to produce better and happier conditions under which the toilers may work and live. Miss Entwistle returned to Blackburn a week ago, and I seized the opportunity to pay her a visit and learn something first hand of the fierce battle which raged round the portals of the "mother of Parliaments", on the evening of 13th February. It was my first personal encounter with a real, live "suffragette," and I must confess that I faced the ordeal with a certain amount of trepidation in view of all one has read of the “raging, tearing propaganda" the woman suffragists carry on. On this occasion, at any rate, I must confess that all my fearsome conjectures were pleasantly and completely dissipated.

It is said that when Miss Louisa Entwistle the young Blackburn Mill girl who went up to London to fight in the “the battle of the suffragettes," took her stand in the docks at the Westminster Police Court the morning after she and fifty others of her sex made the now famous raid on the House of Commons on the opening day of the present session, somebody in court, struck with her youthful appearance, exclaimed, “Votes for children!". Miss Entwistle pleads guilty to the accusation of youthfulness, for she does not attain her majority until near the end of the present month, but despite this talk with her reveals the fact that she has clear and well-formed ideas on many of the social and political questions of the day, and a strong and burning enthusiasm for the cause she has taken up. She looks forward to with a bright hope to the time when women may take their part with men in the endeavour to produce better and happier conditions under which the toilers may work and live. Miss Entwistle returned to Blackburn a week ago, and I seized the opportunity to pay her a visit and learn something first hand of the fierce battle which raged round the portals of the "mother of Parliaments", on the evening of 13th February. It was my first personal encounter with a real, live "suffragette," and I must confess that I faced the ordeal with a certain amount of trepidation in view of all one has read of the “raging, tearing propaganda" the woman suffragists carry on. On this occasion, at any rate, I must confess that all my fearsome conjectures were pleasantly and completely dissipated.

Photograph of Louisa from BWT

Miss Entwistle Described

If Miss Entwistle is to be taken as a typical example of the genus suffragette, then the pictures we have had of her friends have been not merely considerably overdrawn, but rather the work of some particularly gifted imaginations. While yielding the palm to none of her colleagues in enthusiasm for women's suffrage, the young lady who has removed the “disgrace" which Mrs Cobden Sanderson remarked rested upon the fair name of Blackburn has certainly none of that desire to make herself into a mock martyr which has been attributed to the suffragettes generally, and when telling me the story of her adventures in London indulged in no heroics or false modesty. She told me in simple straightforward Lancashire fashion, without embellishment, and expressed her views on the question generally with the same plain simplicity. Above all, she had the saving grace of humour, and I could not resist joining in her merry laugh as she told me how two policemen picked her up bodily and carried her across the street during the scrimmage at Westminster, only for her to run back again and again until her action, in the opinion of the police, at length came under the description of “disorderly conduct" and she was marched forthwith off to the Cannon-row Police Station.

TOLD IN HER OWN WORDS.

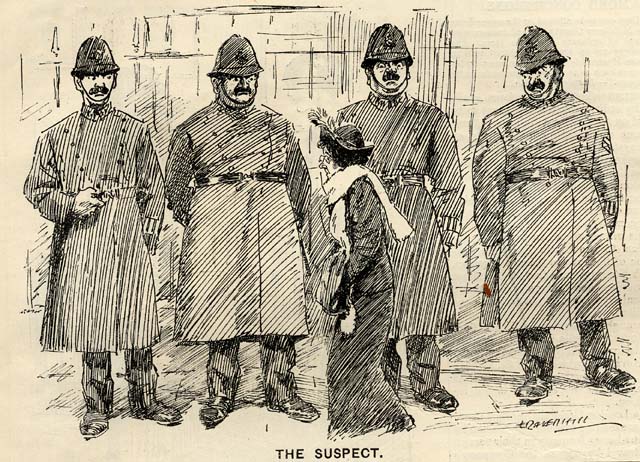

And now to let the story be given in Miss Entwistle's own words. “I left Blackburn on Tuesday" (the day before the incidents at Westminster) she told me. “We had the meeting on Wednesday in the Caxton Hall, and then we decided to go to the House of Commons. We had our battle cry, 'Rise up, women,' but we went quite in an orderly way along the streets in procession, and the traffic was held up as we passed across the roads. When we got to Westminster, however, the police tried to stop us, but we told them we had come there for a fixed purpose. It was through us being so determined that the police stopped us. I got them right angry. I expect they thought because I was so little they would soon dispose of me. I got angry, too, and started talking back to them, and they told us to pass along, but we wouldn't. Then two policemen picked me up and carried me across the road, but I got back through the crowd again. Once I saw six policemen lined across the road in front of me, and I called out to them, 'Just fancy, six “bobbies" to a little one like me.' The crowd laughed at that, and then one of them came up to me and said, 'Come along, we've had enough. I'll take you.' We were taken into Cannon-row Police Station, but we were jolly enough there. We were singing songs, 'England, arise!' and 'The Red Flag,' until we were bailed out."

I asked Miss Entwistle if the police were really rough in their treatment of the ladies, and she replied, “Well, the one that took me was a real good sort. He only took me by the arm, but I believe some of the prisoners were taken hold of by the necks."

MISS ENTWISTLE'S PRISON LIFE

Miss Entwistle gave an interesting description of her prison life in Holloway. "It's not bad to be in prison at all" she said. "I wouldn't mind it a bit if I had to go again - for the same cause of course. We had to get up at in the morning at six o'clock and tidy up our cells. Then we had breakfast - a dry loaf and tea. For dinner we had boiled potatoes - no gravy and soup, and for tea we had dry bread again and cocoa. But though the food is plain, it's good, and everything is very clean. After breakfast we had an hour of exercise. We simply walked round and round a ring, one yard apart. I never saw anything sillier in all my life," she added, with a laugh. "We had time a lot of time to ourselves and we could either sew or read. They gave you very good books, indeed. But of course I was glad to come out again after my seven days. It felt very nice to be free".

Miss Entwistle went on to discuss the future of the movement, and said that it would go on in spite of all that was being said about it. They had been laughed at a lot, but if the women did not get what they wanted they would be just as bad to deal with, and worse, than they had been. There were plenty of women ready to come forward and take up the fight. "It is not because we want to make ourselves into martyrs," Miss Entwistle said, earnestly; "it is because the working women suffer so much under the present conditions by which they are oppressed. We don't want to make a name for ourselves, and it is for women who work in the mills, and who have their homes and their children to look after, that single women are trying to get the vote. It is for these helpless women that we are fighting. Our opponents know that if we get the vote we shall alter alot of things, and they are frightened.

WHY SUFFRAGISTS ARE INDEPENDENT OF PARTIES

I asked her why an independent attitude should be taken up at the bye-elections by the suffragists. Would it not be better, I queried, if support was given to the candidate who was nearest to their views? Miss Entwistle was emphatice upon the point. "Don't you see," was her response, "that it is not a party question at all. We have got to get on our side women of all shades of politics. If we are to support the Liberal candidate we shall estrange the Tory women from our cause, and if we say "Vote for the Tory", we shall have the Liberal women vote against us. We are only attacking the Liberal Government because it is the Government. If they don't give us the vote, and a Tory Government comes into power, then we shall attack them until we do get it."

My last question was whether Miss Entwistle intended to return to London to take a further part in the agitation. Her reply was that she “could not be spared from home". I could not help thinking that in some measure it was a reply to those critics of the “suffragettes" who have insinuated that in engaging in the fight for the vote they are neglecting the true duties of womanhood. If, as I say, Miss Entwistle is to be taken as a true type of the suffragettes – and there appears to me no reason why she should not – I cannot help thinking that the criticisms of the “shrieking sisterhood" type have been perhaps a little too harsh. These women feel strongly about the cause they have taken up. Though many consider their authority-defying methods mistaken and short-sighted, one must remember that many of the liberties which the “mere men" of today enjoy had to be fought for in very much the same way.

CANDIDE

back to top

Article by J. Stanley Miller, May 1975

Quarto pamphlet (P13)

Although the Blackburn branch of the Women's Movement was formed in 1895 while the Pankhursts were still working in Manchester being made into a Branch of the Women's Political and Social Union in 1903, Blackburn was not regarded as very active in Women's Suffrage matters.

Upper class women were more interested in social and welfare work, such as visiting cases on behalf of the Charity Organisation Society (formed February 7th, 1895) and arranging socials to provide funds for the District Nursing Association (formed April 28th, 1896). Another activity in which they were involved was the supply of free meals to necessitous children in 1904.

While upper class Blackburn was male dominated, and content to be so, in certain working class areas, women were the dominant sex. A canvasser on behalf of Philip Snowden in the October 1900 Election was surprised to find a Grimshaw Park husband polishing the brass knocker on his front door, and sand-stoning the door step and window sills. Another elector in the same area consulted his wife before announcing that he would take her advice and continue to vote Tory. The explanation probably lies in the fact that women could find more certain work as four-loom weavers than their husbands, since in many mills boys were turned off on reaching 18 or 21 and forced to take outdoor work liable to seasonal unemployment. Since the wife earned more, she took over the male role.

There were reckoned to be 1200 working mothers in Blackburn and agitation were started in the early 1900s for day nurseries or creches. Day nurseries had been organised earlier in St. Peter's district during the Vicarate of Rev. G. E. Hignett, and by Eli Heyworth at Audley in the 1890s. The latter had been unsuccessful as it was reserved for employees of Audley Hall Mills, and when work people moved out of the district, it was no longer convenient for them, the number of children attending declined, and the nursery closed. It was felt that a nursery organised on district lines, and not confined to work people from a single mill would have been successful.

The numbers of Blackburn women workers was at a peak in 1911, when 18, 372 Blackburn resident women textile workers were in employment.

Theresa Billington commented on the lack of interest in Women's Suffrage in Blackburn shortly after her marriage in January 1907:- “20 Lancashire women have gone to jail. Is not Blackburn going to send some representative to show the earnestness of the women in the Town?" Miss Adela Pankhurst and Mrs Snowden addressed a meeting on Women's Suffrage at the Lees Hall, on February 4th, 1907. Louisa Entwistle presided on this occasion, and she was shortly to give Blackburn's answer to Theresa Billington's taunt. Hitherto, Louisa, of 133 Burnley Road, had continued her work at the mill, and addressed meetings at or near the mills. However on February 11, 1907 she was called up on active duty by Emmeline Pankhurst, arriving in London late the same day. On February 12 she was one of the Delegates lobbying the House of Commons, and on being arrested by the Police, charged and convicted, refused to pay the fine, and elected to go to jail instead.

During the same year, 1907, the force of the movement in Blackburn was dissipated by the formation of breakaway and rival movements – the Women's Labour League on February 19; the Women's Liberal League; and the Women's Suffrance Society on December 8th. This splintering was reflected nationally by Theresa Billington's Women's Freedom League of September, 1907.

The cause was also discredited to some extent by a forged letter signed by “Louisa Entwistle" claiming the support for the women of Sir Harry Hornby, the local Conservative, which was promptly denied by Sir Harry's Agent. Louisa's father proved that the letter was not from his daughter, and the signature “Louise" instead of “Louisa", but the harm was done.

There was also considerable anti-suffrage feeling which was voiced by

D. J. Shackleton, M.P.:- “The Factory Act provided that women should not go to work before one month after the birth of a child. “Married women should stay at home. Mill life for women means ready-made dinners, and tasty scraps instead of wholesome food". Opposition found a more active form in the Anti-Women's Suffrance League, founded in Blackburn on April 5th, 1907.

During the early part of 1907 came a trade depression, with 157 applications for relief to the Blackburn Distress Committee, while later in the year there was agitation for a 5% pay increase for textile workers. Both these events sapped the strength of the movement.

1908 saw a meeting of the Women's Liberal League, and on November 25th there was a Demonstration for the Women's Suffrage at the Town Hall. This annual event each November was becoming the main method for keeping the cause alive. This meeting on November 27, 1911 was addressed by Lady Frances Balfour. Now another weakening effect came from an agitation by trade unions for their members not to work alongside non-unionists in the Cotton Mills. This resulted in a General Lockout, but not in 100% union membership.

Militant and other activities ceased on the outbreak of War. Blackburn women found fresh outlets attending the Belgian wounded, and later British, at Ellerslie Hospital, working on the railway, as tram drivers and conductors, and in heavy industry. In 1918 women over 30, who qualified, were given the vote. It was not until 1928 that the vote was extended to all women over 21.

back to top