In November 1868, the Lancashire town of Blackburn was the site of intense electoral activity. The municipal elections, in which all six wards were contested, were held on Monday 2nd November. The borough parliamentary election followed on 16th November then, on the following day, the nominations for the newly created county seat of North East Lancashire. All three of these elections were accompanied by violence, with the most serious occurring, somewhat unusually, during the municipal elections – indeed, a man died two days after the municipal elections from injuries sustained at that contest. Another man was killed during the following parliamentary elections, although the violence was not as serious. During these elections Blackburn became notorious, nationally and internationally, for the extremes of its electoral violence. The violence was notable but what was historically more important is how violence, as an aspect of organised, or semi-organised intimidation of potential voters, followed the extension of the franchise under the Parliamentary Reform Act of 1867. To understand this violence, it must be considered in the broader context of religion, particularly the Conservatives adoption of the radical Protestant agenda of the Orange Order, after Gladstone’s policy on disestablishing the Irish church became a political issue, and changes in campaigning with the extension of the franchise. Employers, assisted by employees, which became an issue in Blackburn when the Liberals accused the Conservatives of using the ‘Tory Screw’, could be interpreted as having its origins in violent action taken against people who did not comply with expected behaviour. The riots and deaths captured the headlines, but a deeper examination of the causes is historically more interesting. This article will examine that context after an account of the violence around the elections.

The violence that made Blackburn infamous began on the Friday before the municipal elections. Violence broke out on the Friday evening near the centre of Blackburn when crowds supporting the Conservatives and Liberals clashed. The police were called out and the rival crowds driven towards different parts of the town, divided by the railway. The Liberal supporters smashed some windows, but no serious incidents were reported in Blackburn’s newspapers. The Conservative crowd was driven towards the Nova Scotia district where, after threatening one public house were the Liberals were holding a meeting, the crowd, numbering in the hundreds, smashed the windows of a public house where other Liberals were meeting. The Liberals retaliated to this by smashing the windows of another public house on the same street used by Tory supporters. During this attack, the landlord was injured when a stone hit him (Blackburn Times, 31 October, 7 November, 14 November 1868; Blackburn Standard, 4 November, 11 November 1868, Preston Herald, 7 November 1868).

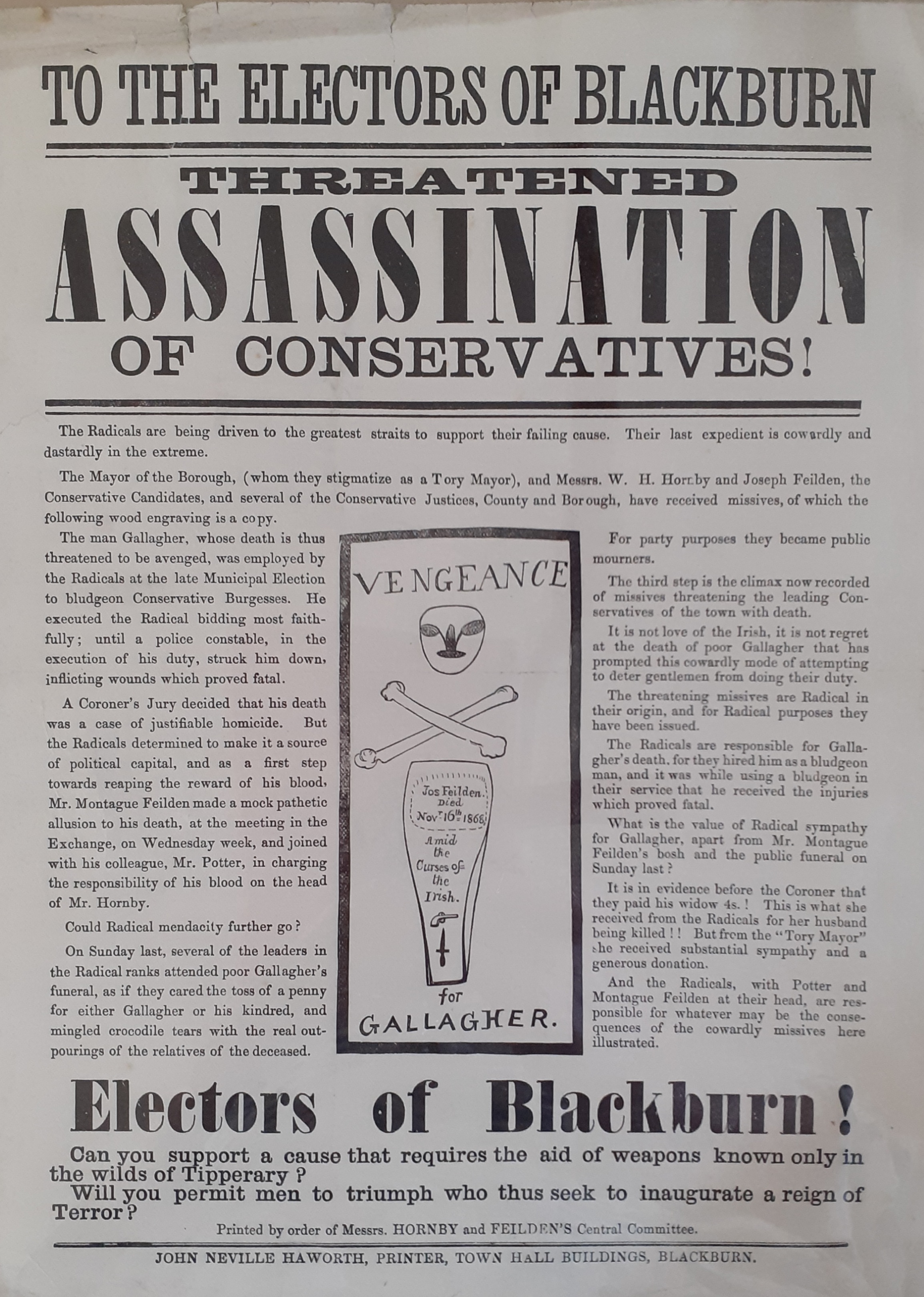

The Mayor responded by calling in the army from Preston ahead of the municipal elections. On the election day itself, armed police reinforcements were also brought in from around the county (1). The municipal elections were hotly contested because both parties believed that success for their candidates would virtually decide the result of the borough parliamentary election. As each ward had only one polling booth, both parties adopted the tactic of monopolising polling booths, with one party taking different booths and preventing supporters of the other party voting. Supporters of the opposition responded, in some wards,by attacking the booths to occupy them for their voters. The result was violence, with the Riot Act read in several wards. Dragoons and police armed with cutlasses were deployed (2). In the afternoon, the Liberals attacked the booth near the Market Cross. During the skirmish, a police constable struck Patrick Gallagher, a young Irishman, on the head with his baton. Two days later Gallagher died from his injuries. At the inquest Gallagher’s wife admitted that she had been paid 4 shillings by the Liberals for her husband’s actions on election day but, when challenged by one of the inquest jurors, claimed that she did not know if her husband had been employed as a ‘staffman’ (3). The day of the municipal elections was the most violent of the 1868 election period in Blackburn with most of the violence resulting from assaults on individual polling booths.

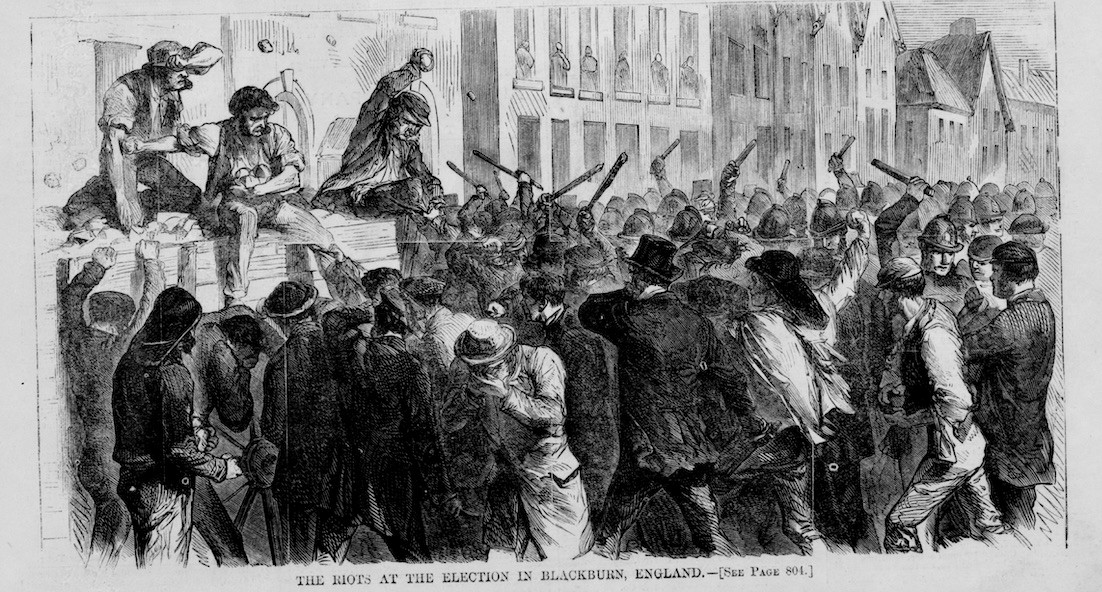

The severity of the violence around the municipal elections made Blackburn infamous, nationally, and was even reported, and editorialised, in the United States. The Manchester Guardian reported the election, including details of the violence (4). However, The Times published a dramatic and far more graphic report in which it claimed ‘all along the pavements streams of blood were flowing, and the sickening sight of men with blood flowing from their heads and faces met one at every turn’ (5). The Times’ report was later reprinted in Annual Register (6). By December Blackburn’s reputation for electoral violence had reached the United States with Harper’s Weekly using the riots, which it incorrectly ascribed to the parliamentary election, to extol the superiority of the United States electoral politics by claiming ‘never has it occurred in the history of this country that a popular election has been accompanied by riotous manifestations so violent and so extensive as those which attended the elections in England’. Harper’s Weekly emphasised these comments with an accompanying, fanciful, illustration of the riots in Blackburn (7). After the municipal elections the country, if not the world, was watching Blackburn.

Harper's Weekly, 19th December 1868, p813 Violence was limited during the nominations and polling for the borough parliamentary election. Unlike the municipal elections, the mayor and the district magistrates met to plan precautions to prevent disturbances. Application for troops was made to the Home Office after which eighty infantry and forty cavalry from Fulwood Barracks in Preston were made available. 460 men were sworn in as special constables but only five country police officers were provided. In previous elections the hustings had been on the market ground in the centre of the town. For both the borough and county elections, the hustings were moved about half a mile from the town centre to a larger area of ground which could hold 70,000 people. The ground was levelled, and stones removed. A seven feet high wooden barrier was erected to keep apart the supporters of both parties. Planning probably helped reduce the threat of violence but the increase in the number of polling booths was probably the major reason for the reduction in violence. For the municipal elections, only six polling booths were used, one in each ward. Because the 1867 Reform Act required one polling station for no more than 500 people, 23 polling booths were provided for the borough election. Not only were the number of polling booths increased but also twenty special constables, ten from each party, were stationed at each site. This made the tactic of a party’s supporters, paid or otherwise, occupying polling booths during polling very difficult.

Despite these precautions, violence did break out which included a further fatality. During nominations, the Tory supporters threw stones when the Liberals displayed a representation of the ‘Tory Screw’ (Tory factory owners sacking Radical supporters). A councillor sent for the dragoons, but the mayor ordered them back to their billets, and the election passed without rioting. However, there were clashes between crowds of Conservative supporters and Liberals/Irish during the afternoon and evening in Penny Street and Starkie Street. This area was a flashpoint because Penny Street, a major thoroughfare leading north from the town centre, was adjacent to an Irish quarter. It was also the main route to Brookhouse where William Henry Hornby, one of the Conservative candidates, had his cotton mills around which most of his employees lived (8). As well as mass fights, several individual assaults were recorded during the election day, the most serious of which resulted in a death (9). In the evening, Thomas Whittaker, who was intoxicated, died after being attacked while walking through an Irish quarter to the west of the town centre. It was alleged that Whittaker was attacked because he shouted a slogan in support of one of the Tory candidates. Two men, Thomas Fallon and Daniel Duxbury, were charged with murder but, after their trial at the Liverpool Assizes, both were found not guilty (10).

The following morning was the appointed day for the nominations for the county seats of North East Lancashire. These passed quietly. In the afternoon, the results of the borough elections were declared after which a further clash between Conservative supporters and Irish and Liberals happened on Penny Street., A crowd of Tory supporters paraded displaying a gamecock, a symbol associated with William Henry Hornby, who had just been elected. Some Liberal supporters attacked them, and yet another riot ensued. Although there were mass fights and individual attack which resulted in a death, the violence was not as severe as that during the municipal elections. To understand the reasons for the violence, it must be put into the broader religious, social and political context.

The violence that began on the Friday before the municipal election and continued until the official declaration of the result of the borough election made Blackburn infamous. However, in his speech when he was reappointed as mayor, Alderman John Smith traced Blackburn’s problems back to the visit of William Murphy who gave a series of anti-Catholic lectures in October and November of the previous year. He claimed that Murphyism had done ‘a great deal which will not be effaced in this generation’. Also, he claimed that the processions held by both the Liberals and Conservatives before the elections had done ‘no good’ although ‘all those processions went off in as peaceable a manner as any man could wish them to do when such a great gathering of people are brought together’. He continued by accusing both parties of being ‘prepared to fight and … engage men and pay them money and engage bludgeons, too’ but, as a Conservative, he accused the Liberals of starting the fights. He expressed shock at the nature of the violence: ‘we had been used to a bit of punching with clogs and fighting with fists, but never with hammers and knives’ (11). The mayor’s assessment of the role of ‘Murphyism’, the political processions and the nature of the violence compared with previous elections is worthy of examination.

William Murphy toured extensively around England between 1864 and 1871, giving virulently anti-Roman Catholic lectures. Often, Murphy’s visits were accompanied by violence when Catholics tried to stop him giving his lectures, and Protestants retaliated. For instance, serious rioting had broken out during his visit to Birmingham in June 1867 (12). Fearing a similar outbreak of rioting, Blackburn’s mayor and borough magistrates, on the advice of the Chief Constable and after a memorial from inhabitants, attempted to stop Murphy lecturing but, after a confrontation on the evening of the first lecture, permission was granted under strict controls (13). Although no serious rioting occurred, there was a confrontation between Protestants and Catholics, whom the local press reported as being Irish, after the final lecture on 2 November (this lecture was given by John Houston not Murphy). A crowd accompanied Houston back to his lodgings, then moving onto the nearby Catholic church and its adjacent priest’s lodgings which were guarded by armed Irish and Catholics. There were fights during the evening and into the morning, but they did not escalate into a riot (14). Murphy concluded his visit to Blackburn by arranging a ‘Great Protestant and Orange Demonstration’. The Conservative Blackburn Standard’s report of the procession was scornful and derisory, mocking the regalia and the prominent display of orange and blue favours. Despite serious provocation from Murphy and his associates, including the firing of pistols, no serious confrontation developed between Catholics and Protestants, partly due to the call for restraint by Catholics – posters to that effect were posted around the town (15).

After March 1868, when the Liberal leader, William Gladstone, made disestablishing the Irish church a national political issue, the relationship between the Conservative party in Blackburn and both Murphy and the local Orange lodges changed. When Murphy returned in June 1868 to give more lectures, he faced no interference from the mayor and the magistrates, even though they had received a petition with 900 signatures against Murphy lecturing (16). The Liberal-supporting Blackburn Times did not directly accuse the local Conservatives of using Murphy for their own political purposes but, after Murphy questioned the character of the two Liberal parliamentary candidates, the paper concluded that it ‘would lead every right-thinking person to infer that his visit to the town had not been entirely by the prompting of his own feelings’ (17). The relationship between local Conservatives and the Orange lodges became clear in July with the procession and celebrations of the Battle of the Boyne. There had been Orange lodges in Blackburn since before 1830 but, until 1868, any celebration of 12 July which may have occurred had received no attention from the local press (18). This changed after the Great Protestant Demonstration on Saturday 11 July 1868.

The Great Protestant Demonstration can be viewed as the first public event of the 1868 election campaign. Not only was it a celebration of the Orange Order, but also a display of support for the Conservatives. The Orange Order and the Liberals had organised several public lectures on the Irish Church from April, but this was the first mass demonstration to include representatives from one of the main political parties. The parade was led by the men and women of Blackburn’s Orange lodges, wearing orange and blue regalia. They were followed by members of the Working Men’s Conservative Clubs, and workmen from

William Henry Hornby's Brookhouse Mill. Many flags and banners were displayed bearing such mottos as “Our Glorious Constitution in Church and State” and “The Altar, The Throne, and the Cottage”. The procession’s route took in parts of north, west and south of the town, avoiding the Irish quarter near Penny Street, before finishing outside the Town Hall. The Blackburn Standard estimated that 4,000 people took part, judging it a great success. However, The Blackburn Times thought that only between 2,200-2,800 took part, dismissing it as a failure because half were women and a third were youths. It calculated that only 500 voters under the new franchise joined the procession. Both newspapers did agree that the procession took 30 minutes to pass. The demonstration concluded with a tea party in the Town Hall, attended by over 1,000 people, who heard speeches by several of Blackburn’s ministers, representatives of the Orange Order and local aldermen. Alderman James Thompson declared ‘we have nailed our orange and blue to the mast, and that we will never be ashamed of our colours, nor be satisfied until the orange and blue are at the head of the poll on the election day’. Alderman Thompson’s remarks made it very clear that this was not just a display of Protestant loyalism but also the opening salvo in the Conservatives’ election campaign.

The Liberals held a counter demonstration on the same day. The Liberal’s demonstration took the form of a mass meeting on Blakey Moor, near the town centre, with speeches given on two stages in support of Gladstone’s policy on the Irish Church and promoting the two prospective Liberal candidates, Montague Feilden and Gerald Potter. Bands played and the green liberal favours displayed prominently. The Blackburn Standard ridiculed ‘an intoxicated man displaying green colours, who dubbed himself as the president of the next republic’ who began the proceedings. The verdict on the success, or failure, by the local press went along partisan lines; the Blackburn Times judged it a success, with 7,000 people taking part, and the Blackburn Standard a failure, with a meagre crowd of around 1,000 bolstered by people from Darwen, a neighbouring town. After the speeches a large number left, intending to march to the Victoria Reform Club, near the town centre. During this march the Liberals met the Orange procession and, as the Blackburn Times noted, ‘the fears of those who anticipated that it would give rise to an undesirable exhibition of party feelings and thereby lead to some disturbances were to some extent realised’. When the two processions met, fighting broke out with men on both sides using staffs, resulting in several serious injuries. The clash only ended after the police, using truncheons, intervened. This could be considered to be the first outbreak of violence in Blackburn during the 1868 election campaign. Further fighting broke out on the evening of the demonstrations. There was a riot on Penny Street, near an Irish quarter, when the prospective Conservative candidate William Henry Hornby’s employees, on their way back to Brookhouse from the procession, clashed with Irish and Liberal supporters. The flashpoint appeared to have been the display of colours by both sides, as the Liberals and Irish wore green favours and the Conservatives orange and blue. The Orange and Conservative demonstration and the Liberal meeting set the pattern for confrontations and violence when the election campaigns began in earnest in October (19).

The general election in 1868 was the first under the extended franchise introduced by the Reform Act of 1867. Blackburn became a parliamentary borough under the Reform Act of 1832. As a parliamentary borough the electorate was all adult males who were the head of a household that occupied a house with an annual rental value of £10. Under this franchise the electorate in 1832 was 627. By 1865 the electorate had increased to 1.845 (20). Under the Reform Act of 1867, the borough electorate was extended to all men who owned or occupied a house for at least a year ending on 31 July on which he paid the poor rate. Also, the act introduced a lodger category. All men aged over 21 who had been tenants for at least a year of a property or lodging with a rental value of at least £10 a year (21). Under this extended franchise Blackburn’s borough electorate increased to over 9,000, which, for the first time, included many working-class men. New forms of campaigning had to be introduced to attract the new voters. The example set by William Murphy’s Grand Protestant Demonstration, held in November 1867, and followed by the Orange Order, with the support of the local Conservatives, in July 1868 was used as part of their campaigning by both parties in the build-up to the parliamentary election. Demonstrations increased animosity between supporters of political parties which, in some cases, led to violence. Some of this animosity may have been encouraged by payments from the parties, but little direct evidence exists, although many accusations were made.

Organised demonstrations that proceeded around the town had not played a part in electioneering before 1868. Any processions did not take a formal route but only happened immediately before the nomination and polling days, as in 1865 when, after a monster meeting in support of Potter on Blakey Moor on the eve of nominations, Potter was carried on the shoulders of a crowd to his hotel (22). The candidates were often accompanied to nomination and polling by a procession, as happened in the 1865 election. Such processions did not play a part in campaigning but were only part of the spectacle of the election days (23). This introduction of political demonstrations was probably what Alderman Smith was alluding to in his speech when he was re-elected mayor in 1868.

The Liberals held a great demonstration on 11 October, over a month before the parliamentary election (24). Like Murphy’s demonstration and the Orange and Conservative procession, it took a route that included many parts of the town. The Liberal’s route was estimated as being three and a half miles long, visiting most parts of Blackburn, but avoiding Brookhouse, Hornby’s stronghold. Reform Club members met at several clubs in different parts of Blackburn then paraded to Blakey Moor where the procession formed into order. At the head of the procession were carriages and mounted horses for the Liberal candidates for Blackburn borough and the North East Lancashire county seat, local councillors and other dignitaries accompanied by the Borough Band. Prominently displayed was Henry Hunt’s flag from his victorious campaign in Preston in 1830. The Reform Clubs followed, including women, carrying flags and banners and wearing pink, green and white favours. The flags and banners displayed such slogans as “Civil and Religious Liberty” and “The emigrants will return when justice is done to Ireland”. The Irishmen of Blackburn carrying a flag bearing the words “Erin-go-bragh” [Ireland Forever]. The Blackburn Times estimated that 8,800 people were in the processions which was two and a half miles long and took 45 minutes to pass. A rear-guard of 200 men followed the procession and behind them were what the Blackburn Times described as ‘about 500 roughs with orange and blue paper in their hands. The Blackburn Standard claimed that men were paid to carry flags and banners, 1 guinea for the large flags and 6s 6d [32.5p] for small flags and banners, and that ‘liberal libation of beer’ was provided the men of the rear-guard. The display raised party feelings resulting in several altercations leading to arrests and convictions.

Violence erupted throughout the day of the Liberal demonstration and extended into Sunday. The violence began with attacks upon the members of various Reform Clubs and the Irish Brigade as they prepared to parade into Blackburn to join the procession. Members of two Reform Clubs near Hornby’s Brookhouse area were attacked, and another group of Reform Club members were confronted as they passed another area where Hornby had a factory and near where the other Conservative candidate, Joseph Feilden, had his family estate. The Irish were attacked as they passed the Conservative club in the town centre with the Blackburn Times claiming ‘a notorious Alderman, too, was on the prowl, near at hand, ready also, as a magistrate and ex-mayor should be, to give his roughs the benefit of his counsel’. Several attacks were made on the procession, mainly in attempts to seize flags and banners, but the most serious incident was when an attempt was made to break the procession. As noted above, the procession was followed by a rear-guard of 200 men and 500 men wearing Tory orange and blue favours. Three policemen walked between the two groups. About half way around the procession route, a major fracas developed. Two members of the Conservative group, headed by a man carrying a besom, or broom, decorated with orange and blue ribbons, began throwing stones, injuring a policeman. A clash between 600 or 700 people ensued with an estimated 100 throwing stones. The local newspapers provided no details of how the clash was brought under control but, probably due to the actions of the police, a major incident, involving serious injuries, was averted. Four men were arrested and convicted, two from each party. The chief constable wanted the men charged with riot, but the magistrates refused with one dismissing the exchange as ‘an election row’. Instead, the men were charged and convicted of aggravated assault on the police.

Although most of the incidents appear to have been Conservative supporters attacking Liberals, the Liberals were not blameless. The incidents involving Liberals included four men, who were part of the procession, convicted of assaulting an elderly man and another man for hitting a boy riding a pony, bedecked with blue and yellow favours, into the procession. The boy’s actions were interpreted differently, depending on politics. To the Conservative Blackburn Standard he was an innocent going about his work of delivering meat, whereas to the Liberal Blackburn Times his basket was empty and he rode his pony into the procession as an act of provocation. No action was taken against the boy.

A further major incident occurred after the procession. On their way back to Brookhouse, a group of men, led by one carrying a besom decorated with orange and blue ribbons, smashed the windows of a reform club. Five were arrested, including the carrier of the besom. The magistrates acquitted two and gave the benefit of the doubt to another two. The man carrying the besom was convicted because the magistrates thought he ‘acted very improperly in carrying the besom, for his so doing was calculated to cause a breach of the peace’. It is possible that magistrates’ judgement was not entirely impartial but their view on the provocative display of Conservative colours, which had become associated with Church and State, is significant. Whether the colours alone were provocative or being displayed on a besom gave added significance is not clear. The Blackburn Times, in an article satirising the besom carrier that followed the procession, opined ‘that its bearers belonged to the “Ignoble Order of Amalgamated Political Night-soil Men and Scavengers”’. It is possible that carrying a besom bedecked with favours had a local meaning that has been lost.

Two weeks later, on 25 October, the Conservatives responded by holding their own demonstration and procession. Liberal supporters did not attack the procession concertedly because the chairman of the Liberal election committee had published instructions to let the event pass peacefully. However, a few incidents did break out and some fighting developed afterwards. The route followed by the main procession was not as extensive as the Liberal’s, visiting only the north and south of the town before assembling outside the town hall. However, nine groups assembled in different parts of the town, including a party from Darwen which marched from the railway station. In that way most of the town was covered, although the main procession and the sub-groups avoided the Irish quarter near Penny Street. The procession consisted of 18 carriages containing 90 people, including the Conservative candidates for Blackburn borough and North East Lancashire, local councillors and aldermen and other dignitaries, a waggon containing 30 men and boys and 9 brass and 5 fife and drum bands. The carriages and waggon were bedecked in orange and blue while the processionists wore orange and blue rosettes and clothing in the party colours. Most of those taking part came from the Conservative clubs from Blackburn and Darwen but, also, workers from Conservative owned mills joined in. The Blackburn Times claimed that many were paid 3 shillings and given beer to parade and to wear party colours. Flags were carried and at least 25 banners displayed. The flags and banners carried support of the candidates as well slogans such as “the altar, the throne and the cottage” and “the Queen and constitution”. The estimate of the numbers taking part differed depending on political affiliation. The Blackburn Standard claimed that 6-8,000 took part making it a greater success than the Liberal’s demonstration. However, the Blackburn Times estimated the numbers at 5,000 but, after discounting children and women it believed only 1,000 with the municipal or parliamentary franchise took part. Of course, the Liberal Blackburn Times dismissed the Conservatives’ demonstration as a failure (25). Success or failure is not important, what remains notable is the Conservatives joined the Liberals in a new form of political campaigning: the mass demonstration.

Reports of violence during and after the Conservative demonstration were limited. The Blackburn Standard reported stones being thrown at the procession when it passed near the Irish quarter around Penny Street. The route avoided Penny Street but even passing close by was provocative. The only other incidents the Blackburn Standard noted was a few people displaying opposition colours.

The Blackburn Times reported one court case involving two men who had been in the procession, one of whom carried a banner. The two men were fined 20 shillings for hitting another man over the head with a staff as they walked down King Street. Also, the victim had wounds on his ankles from being kicked. One of the attackers lodged a counter claim of assault against the victim but the magistrates dismissed it as he was having his wounds dressed in a barber’s shop at the alleged time of his attack. These were the only reports. The Conservative demonstration passed off relatively peacefully thanks to the appeal by the Liberal election committee. Even the Blackburn Times accepted this, albeit begrudgingly. A major public display of political support passed without encouraging party fever.

Electioneering extended beyond organising party demonstrations. Claims were made that employers who supported both parties exerted undue influence on their employees, but only evidence existed of Conservatives issuing such an instruction. The Conservatives held a meeting to discuss the election of Hornby and Feilden on the 8 October, after which a letter signed by the chairman and other members of the committee was issued on 12 October. The Blackburn Times published this letter on 14 October alleging that it was evidence of what was termed the ‘Tory “Screw”’. The letter instructed ‘all Millowners, and their Managers and Overlookers, and all Master Tradesmen and others possessing influence, should be strongly urged to exert that influence so as to secure … the success of the candidates who adhere to the Constitution in Church and State’. Exerting natural influence were accepted as legitimate, both before and after the 1832 Reform Act, and continued after the 1867 Reform Act. Employers were considered as leaders in the community and employees were to show deference and gratitude. This extended to voting for the party that the employers supported. Some accepted this as legitimate influence whereas others regarded the influence of social superiors over their inferiors to be seen as ‘the most insidious species of corruption, illegitimate influence’ (26). ‘Venal’ constituencies were those where illegitimate influence was ‘exercised through electoral corruption, coercion, or intimidation’ (27). The actions of Blackburn’s Conservative millowners and some of their employees extended into coercion and intimidation.

When the petition contesting the Blackburn election was heard in March 1869 the illegitimate influence by representatives of a Conservative millowner, whom the judge deemed to have been canvassing on behalf of the candidates, caused the election to be declared void and those elected barred (28). However, a case brought under the Combination Act, 1825, provides evidence of how political ill-feeling operated at a mundane level. Thirteen men were summonsed for ejecting two fellow workmen from their place of employment on the day after the municipal elections because the two men had voted Liberal at the municipal elections. One of the claimants, a powerloom weaver, had worked until breakfast when the defendants came to him, stopped his loom and told him to stop working. Then, they threw his coat at him, carried him out of the mill where they pelted him with stones. The lawyer acting for the defendants did not deny the complaint but claimed that the practise had been very common in Blackburn for at least 20 years. In this case the action was politically motivated but was sometimes done when a husband was accused of beating his wife (29). By describing the ejection of workers from a mill for having different politics from his fellow workers as being similar to that employed as community justice against wifebeaters shows that what E. P. Thompson termed ‘the moral economy’ applied to politics as well as personal behaviour (30). The actions were ritualised, from turning off the loom to carrying the considered offender out of his place of work to pelting him with stones. This was the rural practice of charivari, or rough music, brought to the town. The Tory Screw could operate by employers and their senior employees exerting undue influence and even ejecting people from work, but it could also work through ordinary workers acting against their fellows. Whether this was encouraged or sanctioned by millowners is open to question.

Blackburn became notorious for the violence associated with the municipal and parliamentary elections in November 1868. One man died during the violence associated with the municipal elections and another man died during the time of the parliamentary election, although this was not part of an election riot but an isolated incident. The violence around the elections is what captured the headlines but to understand it, the violence has to be considered in the context of issues around religion, in particular the Conservatives adopting the anti-Catholic Orange Order for political purposes, and the change in campaigning that developed after the broadening of the franchise. The Liberal’s accusations about the ‘Tory Screw’, in which employers, with the aid of employees, acted against workers who did not vote Conservative, can be seen in the context of popular action against people adjudge miscreants. The rioting and death captured the headlines, but the underlying causes are more historically interesting. The1868 elections in Blackburn provide an interesting example.

Endnotes

1. Blackburn Standard, 4 November 1868.

2. For ward-by-ward accounts of the local elections see Blackburn Standard, 4 November 1868 and Blackburn Times, 7 November 1868.

3. Blackburn Times, 7 November 1868.

4. Manchester Guardian, 3 November 1868.

5. The Times, 3 November 1868.

6. Annual Register, Part II (1868), pp. 135-6.

7. Harper’s Weekly, 19 December 1868, pp. 813-4.

8. The Hornby family became on of Blackburn’s main cotton merchants in the 1770s and 1780s. The Hornbys were a gentry family from Kirkham, west of Preston. John Hornby moved to Blackburn then, in partnership with Richard Birley, also from Kirkham, and their business founded the Brookhouse cotton mills. (Derek Beattie, A History of Blackburn (Lancaster, 2008), pp. 68-70).

9. Blackburn Standard, 18 November 1868.

10. Doubts exist as to whether the attack on Whittaker was politically motivated. At both the inquest and at Duxbury and Fallon’s trial, the motive for the attack on Whittaker was ascribed to his shouting a slogan in support of Hornby. What was never considered was the relationship between Whittaker and one of the accused, Duxbury. Duxbury’s father was married to the sister of Whittaker’s wife. Whittaker and his wife had been estranged for some time; she lived near to where Whittaker was attacked. On the evening he was attacked, Whittaker had been in the area for some time. He had drunk at a local beerhouse, then tried to enter the Duxburys’ house but had been ejected by Duxbury’s father. Some witnesses claimed that Whittaker had been harassed by a group of women with one claiming that a woman had hit Whittaker. Duxbury’s wife was not called as a witness at the inquest nor the trial. It is possible that Duxbury and Fallon were the attackers, but it is also possible they were covering up an attack done by Duxbury’s stepmother. Whoever was the perpetrator, it was likely that the motive was a domestic dispute rather than a politically motivated attack [Blackburn Standard, 25 November, 2 December, 16 December, 30 December 1868; Blackburn Times, 28 November, 26 December 1868].

11. Blackburn Standard, 11 November 1868.

12. John Wolffe, ‘Murphy, William (1834-1872), public lecturer, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, (January, 2008) https://www.oxforddnb.com/view/10.1093/ref:odnb/9780198614128.001.0001/odnb-9780198614128-e-37796 (accessed 23 October 2018).

13. Blackburn Standard, 16 October 1867.

14. Blackburn Standard, 6 November 1867; Blackburn Times, 9 November 1867.

15. Blackburn Standard, 13 November 1867; Blackburn Times, 16 November 1867.

16. Blackburn Standard, 17 June 1868.

17. Blackburn Times, 13 June 1868.

18. Select Committee on Orange Institutions in Great Britain and the Colonies (1835), pp. 143, 145 – in 1835 the Blackburn lodge met at the King’s Arms, Northgate, on the second Monday of the month and there were 95 members.

19. Blackburn Standard, 15 July 1868; Blackburn Times, 18 July 1868.

20. W. Duncombe Pink and Rev. Alfred B. Beavan, The Parliamentary Representation of Lancashire, (County and Borough), 1258-1885 (London, 1889), pp. 315-319.

21. Blackburn Standard, 17 June 1868.

22. Blackburn Times, 15 July 1865.

23. Blackburn Standard, 12 July 1865.

24. The sources for this account are: Blackburn Standard, 14 and 21 October 1868; Blackburn Times 17 and 24 October 1868.

25. Blackburn Standard, 28 October 1868; Blackburn Times, 31 October 1868.

26. Alan Heesom, ‘’Legitimate’ versus ‘Illegitimate’ Influence: Aristocratic Electioneering in Mi-Victorian Britain’. Parliamentary History,

Vol. 3, pt. 2 (1988), pp. 285-287.

27. Angus Hawkins, Victorian Political Culture: Habits of Heart and Mind (Oxford, 2015).

28. Preston Herald, 20 March 1869: the judge declared the election void after Mr Greenwood smiled when his employee, Robert Hindle, told him he was going away so as not to vote in the parliamentary election after he had voted Liberal in the municipal elections. The judge ruled that the circular issued on 12 October had that anyone from employer to overlooker was acting as a Conservative agent. The judge barred the candidates and ordered the election to be rerun but did not fine the elected members because he accepted their evidence that they had not canvassed personally.

29. Blackburn Standard, 25 November 1868.

30. E. P. Thompson, ‘The Moral Economy of the English Crowd in the Eighteenth Century’, Past and Present, No. 50 (February, 1971),

pp. 76-136.

Written by Community History Volunteer, David Hughes, published September 2024