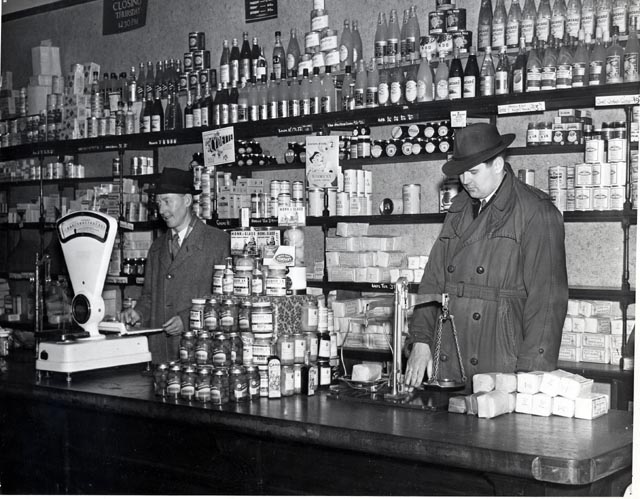

Four years work at Sellers the food Sellers 1945-1949

This is the second instalment of Vince Gibson’s life. Vince has now left school and has got a job at “Sellers the Food Sellers”, Bolton-road. In it he tells about his work as a shop boy and about the people he met.

My first job

I left school in July 1945 aged 14 years. The war in Europe had finished, but chaos reigned in Europe, and the war with Japan continued. Most men of military age were still in the forces which meant employment was readily available for those at home. Prior to leaving school I wanted to be a joiner. based on my experience with Mr Marr our woodwork teacher at Moorgate street, but no apprenticeships were available. My uncle Jack said he could get me a job as a moulder, but that did not appeal to me.

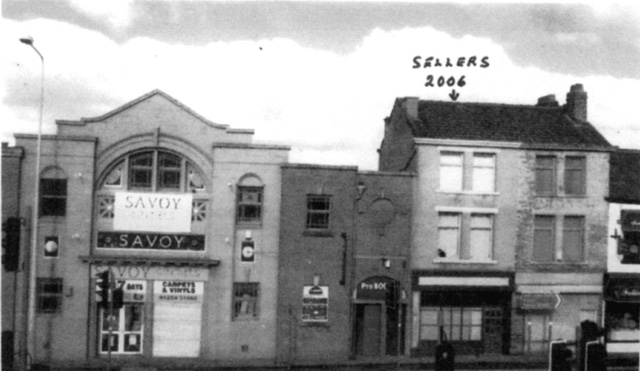

Careers advice was not readily available. Luckily my mother had seen a notice in a shop window for a male sales assistant. An interview was arranged with Mr Fred Sellers, owner of Sellers the food Sellers Ltd. Mr Sellers owned eight grocery shops in the Blackburn area, and a warehouse at the top of Kay street. His office was on Bolton Road above the shop and next door to the Savoy cinema. As a result of this interview I was engaged as a sales assistant and advised to report to Mrs Jones, manageress at the Bolton road shop on the Monday following Blackburn wakes week.

Pay would be 28/- (£1.40) per week paid in cash each Friday. There were no deductions from the gross wage as National Insurance contributions had not been invented. I was required to purchase two sets of white overalls, and a grey coat for warehouse work, further, I was required to present myself for work looking clean and tidy, and wear a tie.

On the appointed day I reported to Mrs Jones, the manageress of Bolton Road branch at 8.10 am prompt. Working day commenced at 8.15 am every morning from Monday to Saturday inclusive. We closed at 7 pm Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday and Saturday. Friday was the late night when we remained open till 8 pm. Thursday was our half day holiday when the shop closed at 1 pm. We closed for lunch each day at 12.45 till 2.15. It was taken for granted, that everyone would go home for lunch, as the premises were locked and vacated. On each Friday afternoon we were entitled to 20 minutes for a tea break. The actual hours worked included unpaid overtime which averaged another four hours per week. Our holiday entitlement was two weeks per year, the two weeks to be taken separately, plus Christmas day, Boxing day, New Years day, Good Friday, Easter Monday, Whit Monday and Tuesday plus two days in September as a late local holiday. You could be required to work at any branch as directed , the cost of travel being your own responsibility. I travelled to and from work by pedal bike, finally, you were not expected to be sick.

Each day I was required to sweep the shop front, and mop and stone the front step. The windows and brasses on the front of the shop had to be cleaned on a regular bases. On my first morning Mrs Jones gave me a duster and a demonstration of how to clean the fixtures and stock. The job required that all the goods should be removed from the shelf, the shelf should be cleaned and then the canned goods should be cleaned and returned to the shelf the right way up, and facing the customer. Correct stock rotation was also a requirement of the job. On this occasion I was required to do all the shelves behind the counter, and report back to her when the job was done. That was Tuesday afternoon.

All the twelve staff were female, which was the reverse of the situation prior to the war. When the men returned from the war, they spent two weeks at the Bolton Road branch, acclimatising themselves with the new reality of food rationing and shortages in general. They then returned to their pre-war branches and continued as if the war had been an inconvenient interruption. The female staff were then sacked. The word redundant was not in the company vocabulary.

Our customers were mainly working class. Some of our customers who were unable to work received food vouchers valued at 2/6 (12½p) per week. Cigarettes could not be included in these purchases. Mrs Woods, a lady who always wore a shawl and clogs had the largest family with twenty children, seventeen of them still living. Most of our customers were weavers or worked within the cotton industry. Conversely we had a small percentage of business people who were friends or business acquaintances of Mr Sellers. One of our customers who lived in Clifton street, off Canterbury street possessed a telephone. Each Tuesday she would telephone in her grocery order to have it delivered. She always introduced herself as follows: “This is Mrs Heppard speaking, wife of Colonel Heppard. Will you please send my rations and those goods you think I ought to have. I will be paying quarterly on X date. Thank you, goodbye”. That was the end of the conversation as she was deaf. This lady was our only exception to the no credit rule. Staff avoided answering the telephone as most of them had never used a telephone in their life.

Each Friday we had a select group of customers who came through the shop and upstairs to see Mr Sellers secretary. She gave each person a parcel wrapped in brown paper and tied with string. No questions were asked and no money was exchanged. Each of these parcels contained rationed and un-rationed foods. The range of goods varied over time dependent on the availability of goods. We never had any complaints from this group of customers, and none of them were registered customers. The shop staff registered for food with Sellers also got special concessions as decided by Mrs Jones. No one ever refused anything because you could always sell goods to your neighbours. Our next door neighbours at numbers 21 and 25 Laxey Road also enjoyed these benefits. At that time both our neighbours husbands were abroad with the Royal Air Force.

To be a regular customer, a person had to be registered with the shop, and we in turn would notify the Ministry of Food . Our food supplies would be controlled by the Ministry of food. (M.o.F) on a monthly basis. The shopping experience was very much a routine affair. Each customer would place their ration books on the counter and simply say “Can I have my rations please?” The sales assistant would check the customer was a registered customer with that shop, then they would cancel that weeks entitlement in the ration book, and collect the ration entitlement together on the counter. The entitlement could vary dependant upon M.o.F. directives. The range of foods rationed included butter, margarine, cooking fat, cheese ,bacon, eggs and sugar. In addition each month the customer would have a basic points allowance which enabled them to choose a selection of canned goods. As customers bought goods the shop staff had to cut the points out of their ration book, and ultimately the points have to be counted, and returned to the M.o.F. Tea and jam rationing was on a monthly basis.

Once the basic entitlements had been collected the customer would ask if anything new had come in, or a more usual phrase would be “Have you got anything under the counter?” usually said with a knowing smile.

Ninety nine per cent of transactions were paid for in cash, no credit transactions were allowed. The receipt of a cheque had to be cleared by the shop manageress. The cash system was pre-decimalisation using £.s. d. including the farthing at 960 to the £. At that time a £10 note which was rarely seen was a large piece of white paper with print on the front only. The reverse side being blank. In those days the sales assistant had to remember the price of all goods, and used a pencil and paper to add up the cost of goods. Finally the cash had to be paid into the till and change calculated. Cash was collected by an area manager who balanced the till each day, and enquired into discrepancies.

Without exception every customer brought their own shopping basket or bag. Plastic bags did not exist. The only alternative available was a cardboard box or in many cases the lady would carry goods in her pinny (pinafore). When vegetables had been purchased, they were weighed from bulk and poured directly into the customers basket, and covered with newspaper. Mill workers called in the shop each lunch and tea time, to ensure they did not miss anything that was available.

The normal work routine for the shop would be as follows:

Monday. General cleaning, which included mopping all floors, stoning the door step, cleaning all outside windows, polishing brass weights and scales. Window and internal displays had to be changed, at the same time customers had to be served and deliveries received.

Tuesday. Weighing up day. Most goods would be received in bulk. Sugar arrived in 2 cwt sacks, plain and self raising flour arrived in 240 lb sacks which had to be emptied into huge metal bins, Danish butter arrived in one cwt barrels, Australian and New Zealand butter was in 56 lb boxes. Dried fruit was usually in 60 lb boxes. When available, dates would be in 80 lb wood boxes sealed with very sharp metal bands. The process of weighing up was a team effort requiring a minimum of three people. One person would break open bulk packaging and fill colour coded bags. The second person would weigh the bags on brass balance scales. This job required great accuracy, otherwise losses would be incurred. Finally a third person would shape and seal the bags and string them if necessary. Government officials checked the accuracy of weighed goods at very regular intervals.

Wednesday. This was the day to ensure all deliveries had been received and stored in the correct location, all displays completed. and shelves filled.

Thursday. This day is the traditional private traders half day holiday, which gave the town a very dead appearance. Closing time was 1 pm, but it could be much later when we actually finished work. Overtime was unpaid.

Friday was always busy serving customers, who would always queue and wait in an orderly manner. Self service has not yet been invented. Friday is pay day for most weekly paid workers, therefore most weekly shopping is done. As the shop is open till 8 pm we have an official twenty minute break for tea. When the shop closed for the day we had to tidy up and refill shelves. Often it would been close to 9 pm before we finished work and go home.

Saturday. The routine today was customers in the morning very much in the normal routine, as weavers worked on a Saturday morning. After lunch the tempo changed. Customers tended to be in a more relaxed mood. Late after-noon was an opportunity to catch up with the paper work associated with the rationing system. All the points and coupons have to be counted and bundled for delivery to the Ministry of Food. Stock control returns had to be completed ready for food inspectors to make spot checks. The “black market” was a thriving activity, of great concern to the government.

My work routine

Apart from my shop front responsibilities the first part of my week would usually be associated with the preparation of the basement warehouse for the reception of goods. All the cases of canned goods should be in their correct place and in the correct order for stock rotation purposes. Cases for filling shelves should be taken up to ground floor level, and part cases returned to stock. Sacks of pinhead oatmeal, barley, dried peas, cereals, soda etc should be checked for security against mice and any damage reported. Small items and small cases of goods should be stacked on shelves. Cases of jam, sauces and other bottled goods should be placed to avoid the possibility of damage. Once the warehouse is in order, space must be made available for the reception of goods from our Kay Street warehouse. The company owned a pre-war Bedford van which had been designed for carrying ladies dresses in a previous age, therefore it was not best suited to carrying heavy groceries. When ex army surplus vehicles became available Mr Sellers bought a Bedford van which was more suitable for our purposes. The van was still in military livery. Many of our supplies came via the London Midland and Scottish Railway which made intensive use of horses and carts. The stables which accommodated around forty shire horses were behind our shop. The most unusual delivery vehicles were the bright red Trojan vans owned by the Brooke Bond tea company. The vehicle engine noise was unique as they were powered by a two cylinder horizontally opposed air cooled engine. They were one of the last vehicles still using solid tyred wheels.

My final job each day was to find the shop cat. Usually it could be found next door in the Savoy cinema enjoying the warmth and presumably the opportunity to catch mice, as evidenced by number of occasions it caught it’s own supper. The patrons of the cinema did not seem to be impressed with the cinema attendant and myself searching up and down the aisles with torches. Cats were an essential member of the shop team as controlling vermin was always a problem. We had a good working relationship with a local fish monger’s shop which ensured a regular supply of fish heads for our cat. Canned cat food had not yet become available. From time to time customers would ask to borrow the cat for a weekend to help then clear their home of mice. Usually the exercise was very successful unless they provided the cat with a comfortable bed and good food. During the four years I worked at Sellers, we lost one cat to a customer as the cat preferred domestic bliss to our shop. The only heating in the three story building was a very small coal fire in the kitchen.

During the latter half of the 1940s the Nova Scotia area of Bolton road ,was a busy trading area due to the density of housing. Next door to our shop was the Savoy cinema which provided a lot of passing trade. Saturday afternoon was particularly busy when there was a children’s matinee. Children would call in the shop to buy ½ lb of broken or soft biscuits to eat in place of sweets. When we had sold out, some of the helpful children would offer to break some biscuits for us. Very close bye were two banks, three butchers, two ladies wear shops, one potato pie shop, a saddlers (for horse leathers etc). a basket maker who would weave a basket for you, and the largest shop was Whittles furniture manufacturers and retailers. The furniture was made on the premises, and you could order furniture to your own specification. One of the most popular shops was Aspden’s cycle repair shop. This shop sold second hand bikes and would have a go at repairing anything. The business was run by Mrs Aspden who was a hands on person prepared to get dirty. Having said that she often wore a genuine fur coat while repairing bikes. During 1946 she went on a four week holiday to America, crossing the Atlantic from Liverpool. She was wearing her fur coat of course. At that time most of our customers could not afford a half day trip to Blackpool.

Looking further along the road there was a post office, a newsagent, a pawn shop complete with the traditional three brass balls. This shop also had one window dedicated to goods which had not been retrieved. At the corner of Hall street there was a specialist cycle shop owned by Tommy Hirst. He represented England in the 1936 Olympics. At the corner of Bolton Road and New Park Street was an up-market men’s outfitters owned by Jack Chadwick. a well known cricketer. Further along the road was a decrepit pet food shop owned by an old couple. The shop window had a magnificent display of dead flies and wasps. Across from the pawn shop was a hardware shop, owned by two strange ladies, which was always in darkness. On entering the shop a loud bell would ring announcing your presence. The bell being operated by two loose boards in the floor. Their window display always featured “Warfarin” rat killer no doubt indicating a problem in the area. Today the medical world use this product on a regular basis to cure patients. Apart from three public houses there was also a Men’s lodging house, usually referred to as the doss house. This building was located at the corner of Bolton Road and School Street. We had roughly twenty customers in that establishment. The smell hit you as soon as you walked through the door. The bare floors were covered in saw dust which when swept helped to absorb urine. Each bed space was minimal, and contained a small cupboard with an integral chamber pot. Those men who were mobile would do errands for the remainder. Two Salvation Army officers who lived in Commercial Street provided voluntary services to provide a little quality to the men’s lives. An unfortunate accident happened outside the lodging house one frosty morning when a horse slipped and broke a leg. It took some time for a vet to arrive and put the animal down, and arrange for the body to be removed. On a lesser scale one of our shop kittens was sitting on the doorstep sunning itself, when a passing greyhound grabbed it and killed it. A catastrophe of a different kind occurred during a period of very hot weather. We stocked large stone jars of sarsaparilla, dandelion and burdock and ginger beer, and on this occasion the heat caused a large number of jars to explode. The situation was dangerous as large shards of the jars were flying in all directions. Fortunately no one was injured, but our cat was convinced it had lost one of its lives.

As our shop is on the main Blackburn to Darwen road it gave me an opportunity to observe the passing scene. The LMS Railway provided a large number of heavy horses for basic haulage. Occasionally two horses would be coupled together in tandem fashion. The railway also had lighter horses for pulling parcel vans. Other traders had horses for delivering coal and milk. Ponies would be used for ice cream carts, and for rag and bone men. A favourite for children was the hot potato carts in busy locations. My uncle Jack owned a horse which he used for his coal business. Within a short period of time a horses get familiar with their round, and the people who will give them a treat. On May day each year most horses would be dressed in their best harness and brasses, including straw hats. Thwaites Brewery still use horses for local deliveries. The main public farrier in Blackburn was based on Canterbury Street very close to St Mary’s school. We could watch the horses patiently queuing up for new shoes. At certain times of the year we had herds of sheep crossing the iron bridge (now the Wainwright bridge) on their way to the abattoirs. Each year when the circus arrived in town by train, the elephants would walk from the railway goods yard to the horse stables linked together by trunks and tails. The procession was usually led by a young lad mounted on the leading elephant.

There was only a small number of cars on the roads. Very few people owned a car, and those who did own a car were subject to very strict rationing. Most cars were of pre-war design with basic facilities. Manufacturers had to export new cars to help the economy. Commercial vans came in many shapes and sizes and had an alarming ability to rust. Heavy lorries were slow and cumbersome, cyclists would often hold onto the tail boards of lorries for a tow up hills. Trams ran in Blackburn till 1949. The Blackburn trams had an olive green and cream livery, and were always in good condition. Darwen also had trams, red and cream in colour and older in design, with the exception of two very modern streamlined trams with central doors. The trams finally retired in 1949 and there are no surviving. vehicles. Occasionally we had steam driven heavy goods wagons, usually based in Cheshire and North Wales. As they depended on solid fuel and a live fire, they often left hot cinders in the road.

On one occasion Mr Sellers allowed me a Saturday afternoon off work to attend a football match at Ewood Park football ground. The match was a cup game between Burnley and Liverpool before a crowd of 51,000 people. I think the game ended in a draw. On that day Bolton Road was crowded with people walking to and from the game. Regardless of the weather on match days Blackburn Corporation used open top trams.

By mid 1949 rationing had become more severe, and the economic climate was in trouble. At this time King George V1 wrote to me suggesting I help him run the Royal Air Force. He wants me to go to RAF Padgate on Monday 8th August before lunch. He has offered to pay me 28/- (£1.40) per week less 3/6p (17½p). which he suggests I send home to my mother to help with the house-keeping money. I felt I had to accept his invitation even though I would return to the rate of pay I was earning four years ago. This brings to an end my job at Sellers. The law says I am entitled to return to my job.

The picture below shows Sellers property in 2006

back to top