This article was written by local historian Gerald Schofield. It was done as an essay for a local history course for the “Open College of the North West”, stage A.

It gives a clear and concise history of the loom breaking riots that happened at Blackburn and district in 1826, and the consequences of the riot for a number of local people.

The article was written in May 1998.

Introduction

They came to Blackburn on the 24th April 1826, common folk, in their thousands with only one intention the destruction of all the power-looms they could find. The wrecking of machinery was not new to the district. Had not “Hargreaves” of Stanhill been sent packing in 1768, him, and his “Spinning Jenny”? The Peel family had been put to flight after twice having their factory at Brookside, Oswaldtwistle put to the hammer; the last time being 1779. As in that year, 1826 saw much poverty about, the county was in the grip of an economic depression, but to the textile workers it seemed that once again new machinery was the cause of their hardship.

Why then, should men and women with no apparent leadership, and in the main law-abiding take to the roads of East Lancashire with destruction in mind? They were not revolutionaries bent on political change; in fact they were not even at odds with Parliament, though by its neglect of them they should have been. The riots in this town were only part of the general disorder in East Lancashire. Though handloom weavers were at the fore, they were not alone; amongst those involved in Blackburn were a schoolmaster, and a confectioner. The destruction in Blackburn took less than half-a-day, it was not only machines that were wrecked, but many lives would never be the same by the end of the day.

1 PRELUDE TO THE ACT

After a period of relative prosperity in the early 1820’s, the winter of 1825-26 was to produce nothing but hardship for the cotton workers of East Lancashire. Some of the banks had not the silver or gold to back up the paper notes they had issued. These were recalled; loans were also revoked causing many bankruptcies. The earlier affluence had increased the number of handloom weavers so much so that it was possible for the manufacturers to reduce the wages of those employed at weaving. The handloom weaver at the end of the cotton manufacturing chain, and unorganised was easy prey to the manufacturers. In the good years, 1802-1806, the handloom weavers were earning up to 23s a week[1], by 1826 this had been reduced to less than 8s per week[2]. A dialect letter to the Blackburn Mail of the 15th February 1826 tells of receiving 1s-9d a piece, considering that in 1814 he would have received 6s-9d- one can see the grounds he has for complaint. He tells of having four children and a wife to keep, and that he works from four in the morning to twelve at night. This family, like many others would be surviving, if that is the word , of one meal of oatmeal porridge a day. At the time bread would cost 2d a lb, butter 1s a lb, cheese 7d and butchers meat 7d[3]. In January the cotton spinners of the town reduced the hours of work in the factories to six a day, a loss of 8 hours per day, with resulting loss of pay[4]. On the 3rd of February a Charity Concert[5] was held at the Theatre to help swell the funds of the recent appeal by the town worthies for the relief of the cotton weavers of Blackburn. On the 23rd February a number of people attacked the home of Mr. William Carr, who was CLerk to the district[6]. Windows were broken, and the gardens much damaged, threats were made, and the sum of £50 demanded. A firearm was produced by the household, and though it “flashed in the pan” it was enough to drive away the attackers. Eight men were tried at the Lancaster Assizes in March, all pleaded guilty and were given prison sentences of between two and five months hard labour. One of the men was released after Mr. Carr had interceded on his behalf. In the town's Workhouse[7] on the 14th of March there were 416 inmates, ironically 130 of these were employed at weaving. On the evening of the 14th March when the Market coach arrived from Manchester it was attacked by the gathered crowd, with stones and other missiles. The windows, and panels of the coach were damaged, as were some of the passengers, and to quote the Blackburn Mail of the 22nd March “One even had his hat knocked off.” On the 28th March [8] between seven and eight in the evening the Manchester coach was proceeding at speed along Nova Scotia on its way to the Old Bull Hotel. It was as usual carrying some of the town’s cotton manufacturers. An elderly man, John Ward, walked in front of the coach, and was hit by the leading horses, from the resulting injuries he died. The driver of the coach, Robert Parkinson, was tried for manslaughter, at Lancaster Assizes on Saturday 12th August. In his defence he told the court, that it was usual for the coach to have missiles thrown at it as it passed through this part of town. Having been hurt by these in the past, he drove fast for the safety of his passengers, and himself. The jury found him “Not Guilty” and he was discharged. In late March the weavers presented yet another petition relating to their condition, but like the many before it, it was ignored. On Saturday 1st April[9] the Manchester coach once again came under attack from the crowd assembled outside the Old Bull, it was quite easy to get stones to use as missiles as the surrounding streets were loosely paved with water worn cobble stones. This time not only was the coach damaged but number of passengers were badly hurt. The Riot Act was read. One of the stone throwers, Thomas Bury, was arrested by John Kay the Constable of Blackburn. Bury was taken to the Duke of York Inn, on Darwen-street. Some of his associates once the military had moved away broke into the Inn, and Bury escaped. However, Kay rearrested him the next morning, this time he was taken to Preston House of Correction to await trial. On the 15th July he was tried at the Preston Sessions, and found guilty of riotous assembly, and breaking the windows of a stage coach, and was given an 18 month gaol sentence[10]. Two others were tried at the same time for rioting after the Riot Act had been read, J. Cook, who was sent down for four months, and T. Entwistle, who collected a twelve-month sentence. On the 12th April the Blackburn Mail gave in detail the number of families who had been given relief, the Grimshaw Park area contained the largest number drawing relief: 235 families, closely followed by the 225 families in the Syke and Moor-street areas. In the sixteen areas of the town there were 2,233 families drawing from the fund. Taking the average family to contain six members, then aid was being given to over 13,000 souls. There was also concern at the numbers of people in the Workhouse; this had risen to 690, contained in buildings designed for the use of 500.

Reports reached Blackburn on the 19th April that a number of persons had assembled, and that they were intent on attacking the power loom factory of Messrs. Sykes in Accrington[11]. In fact the windows of the mill had already been smashed, when twenty men of the 1st Dragoon Guards were sent from Blackburn. They returned the following morning saying that all was peaceful in Accrington. The news of the disturbance gave cause for some excitement, and according to the Blackburn Mail thousands assembled in the streets of the town. Once again on the 19th the Manchester coach was attacked. Yet again people were hurt, and the coach damaged. At ten that evening the riot act was read, and two parties of soldiers were patrolling Darwen-street and Northgate. After the attack on the coach the assembled throng caused no further trouble, and began to disperse leaving the town quiet. On the morning of Saturday the 22nd April the Vicar of the Parish Church received a letter from the Secretary of State for the Home Department, Sir Robert Peel[12]. He advised the Vicar that the King (George IV) had made available £1000 for the relief of the poor. The money was to be shared with thirteen nearby townships, £400 to them, the rest, £600 to Blackburn. This was made known to the general public by handbills. The Union Flag was hoisted on the Parish Church, and a peel of bells rang at intervals during the day. In the Manchester Mercury of 22nd April there appeared an appeal for contributions to the “Relief of Cotton Workers in Blackburn”. It contained the following statement; “The poor are not only very patient under their great sufferings but grateful for what has been done for them and declare that the relief afforded has preserved them from actual starvation.

Patience was fast running out, as events from Monday of the following week would show. The poor people of East Lancashire were going to express their feelings in a most violent way.

Notes

1 The History of Wages in the Cotton Trade. G.H. Wood

2 Ibid

3 The First Industrial Society. C. Aspin

4 Codrays Manchester Gazette 28. January 1826

5 Blackburn Mail 1 February 1826

6 Preston Chronicle 25 February 1826

7 Blackburn Mail 15 March 1826

8 Ibid 16 August 1826

9 Riot. William Turner

10 Preston Pilot 22 July 1826

11 Blackburn Mail 19 April 1826

12 Ibid 26 April 1826.

2 THE ACT

On Monday the 24th April 1826 a mass meeting of weavers was held on Enfield Moor near to Accrington[1]. Speeches were made and then the crowd split in to two, possibly three, separate parties. Attacks were made on four factories in the vicinity of Accrington;a total of 174 (178 reports vary) power looms were destroyed. Provision shops were also looted in Accrington.

The mob then started out for Blackburn, an estimated crowd of six thousand, including sixty men armed with pikes :15 to 18 inch metal spears attached to six-foot poles. Some reports say that they met a detachment of 1st Dragoon Guards, 18 men strong, on their way to Accrington. They passed through the crowd without stopping. Others say the Dragoons stopped, and the officer in charge spoke to the assembly[2]. He basically told them to think what they were doing, and to go home. Being told that “we’re starving, what are we to do?” the Dragoons opened their haversacks and gave the crowd their sandwiches. They parted, the Dragoons for Accrington, were they thought that rioting was taking place, the mob to Blackburn, and more loom breaking. The rioters marched along Bottomgate, down Eanam to Salford Bridge, here some entered the Bay Horse Inn. The landlady, Mary Rigby, was made to supply them with food and drink until supplies ran out[3]. As the Bay Horse was known to be a hostel much used by the manufacturers, this was probably an act of retribution.

From Salford the mob marched up Church-street, along Darwen-street, telling the panicking shopkeepers that their property was safe, they had other mischief to do. At about three in the afternoon they turned in to Jubilee-street, making for the mill owned by Banister Eccles and his partners, called Jubilee Mill. It had been built in 1821 as a spinning mill, then fitted with Radcliffe’s improved handloom known as the “Dandy Loom”, from which the factory got the nickname “Dandy Mill.” Power looms had been introduced in 1825 in the bottom four floors of the seven-story mill. The mob led by James Chambers broke open the factory gates and the crowed flooded into the mill yard. Along side Chambers was Thomas Dickenson who shouted to the crowd; “Stand back, let’s come”, as they entered the yard, the pike men took position left and right of the gate to stand guard. Part of the mob entered the factory, and smashing the doors of the rooms got into rooms containing the power looms. They removed the cloth from the looms and started to smash them. Going from floor to floor they demolished everything involved in power loom weaving. The cast iron wheels, and drums of the steam engine were broken and the wrought iron driving shafts proving impossible to brake were ripped out of their supports. The finished cloth was thrown down to the crowd in the factory yard who tore it apart. John Kay, the town’s Constable had been in Darwen-street when the mob passed on their way to the mill, he followed them and went into the factory yard. He stopped one man, but he broke away. It was about now that the residue of the military arrived, some Dragoons who had been left behind when the rest had gone to Accrington and a detachment of 60th Rifles. They, with the Rev. Noble, a magistrate and cleric, entered the factory yard. The Dragoons charged some of the assembled mob taking some of the pikes from them. The Reverend Noble then read the Riot Act to an un-listening throng, some of who started to pelt the soldiers with anything that came to hand. Many of the soldiers were hit, one of them seriously hurt, the soldiers in return discharged their carbines, but fired blanks. Three prisoners were taken and transported by the military to a secure place. By the time the military had stationed men on three sides of the factory, the other side backed by the river Blakewater. Four of the rioters were on the fourth floor when cavalry charged, they ran down the stairs, and out of the factory, shots (for real this time) were fired by the 60th Rifles, and one of the four, John Haworth, was hit in the back by a musket ball, the others made their escape by wading across the river. The rioters having completed their task started to leave the factory, it had taken them thirty five minutes to destroy the 212 power looms, now it was to be the turn of the 25 power looms in the Park Place Mill of Mr John Houghton in Grimshaw Park. On his way out of the Jubilee Mill, Simeon Wright attacked the Reverend Noble, hitting him with a large stick, this was taken from him by the Magistrates' Clerk Dixon Robinson. Wright made his escape. This was the only personal attack of the riots in Blackburn. The Constable, John Kay, and his assistant John Morten then went into the factory, Kay saw Chambers and asked him; “How could you for shame be here? I got work for you in a warehouse in Blackburn only weeks ago.” Chambers replied; “Are we all to be clammed to death?” At this point Dixon Robinson took Chambers hammer from him, and Chambers ran away. Thomas Cain in the employ of Banister Eccles had entered the factory with the mob, he came across Richard Entwistle breaking up looms. Cain, who knew Entwistle, went up to him and said; “This is queer work.” As Entwistle left the factory Cain pointed him out to John Morten who took him into custody, not for long though, for he was seen later at Park Place Mill. The Dragoons who had been sent to Accrington now returned to the town to meet with a most unusual attack[4].

As they reorganised amongst the crowds in Church-street, they backed their horses into a nearby courtyard. This happened to belong to a well known local radical, Samuel Slater, whose wife set about the Dragoons with her broom, driving them back into Church-street. Captain Bray then took his troop to the factory in Jubilee-street, here he was advised that all was now in order, but that the rioters had gone to Grimshaw Park[5]. So with a Lieutenant Morris, and ten Dragoons he made his way to Park Place Mill. The clearing up at Jubilee Mill started, amongst the items collected were thirty-six pikes. Meanwhile, up the hill at Grimshaw Park the mob again assembled. According to Mr John Houghton there were between 5,000 and 6,000 of them. He tried to reason with them but was met with a barrage of stones. The pike men, fewer now, placed themselves at the front, and when the Dragoons, with men of the 60th rifles arrived, they were met with a barrage of stones, and shots were fired at them. The military attempted to disperse the mob by firing over their heads, but to no avail. Captain Bray said later he was reduced to charging the rioters. This had the desired effect[6]. Unfortunately some of the rioters had managed to get into the factory from the other side. The Dragoons tried to get to them by riding down the side of the mill nearest to the canal; in the confusion one Dragoon, and his horse ended up in the canal. Again Captain Bray says that a horse man could not get to the aperture through which the rioters gained access to the factory. During the fighting outside the mill, two men were injured, Edward Houghton—no relation to the factory owner—who was shot in the neck, the musket ball coming out through the roof of his mouth. While the fighting was taking place outside, inside the factory James Chambers, Simeon Wright, Thomas Dickenson, Isaac Hindle and Thomas Leaver were, amongst others, busy breaking the twenty five power looms. Just as they had done at Jubilee Mill, they threw outside the finished cloth, warps, and twists. The crowd once again tore it, and this time threw it into the canal. Leaver shouted to the crowd; “What are you standing there for? You should come in and work like us.” He was later shot and wounded.

Thomas Breakwell, carding master at White Ash[7] had followed the rioters. He knew Isaac Hindle, and pointed him out to John Houghton. The situation was out of hand, the military and the constables unable to restore peace, just looked on. When the crowd were told that all the power looms were broken they started to move away. It was rumoured that there were power looms awaiting fitting at the King-street mill of William Throp, this proved to be untrue and the factory though entered was not damaged. By now the adrenalin was starting to wear off and the crowds started to disperse. The military took control again and anyone caught on the streets was advised to go home. The Manchester coach arrived an hour early, there was a crowd around the Old Bull, a magistrate read the Riot Act, and the crowd drifted away to their homes.

In the session’s room, the men arrested that afternoon were brought before the magistrates, then sent under escort to Lancaster.

Peace prevailed.

Notes

1 W.A. Abram The History of Blackburn

2 Chris Aspin The First Industrial Society

3 G.C. Miller Evolution of a Cotton Town

4 G.C. Miller Blackburn Worthies of Yesterday 5 Blackburn Mail 3 May 1826

6 Letter from Captain Bray, other details of the riot were taken from newspapers and court reports.

7 The Factory of Mr James Bury at Accrington.

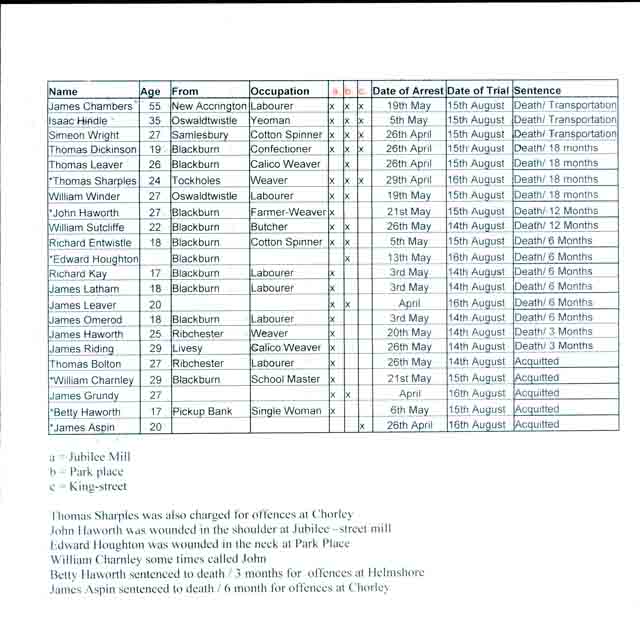

3 RETRIBUTION

After the initial six prisoners were sent to Lancaster the following weeks would see a steady stream of men and women following them. The military were re-enforced. On Monday 24th April a troop of Enniskillen Dragoons arrived from Burnley, to be followed later that evening by another troop of 1st Dragoon Guards[1]. Tuesday 25th April saw more arrivals, a troop of Queen's Battalion arrived to be dispatched immediately to Clitheroe, news having been received that trouble was expected. At four in the afternoon a detachment of the 60th Rifles arrived from Manchester having started out at six that morning. It was said that they were exhausted , having marched with full pack, this would be understandable. The arrests of the rioters took place mainly at night . It became a standard operation, the suspect’s cottage would be surrounded by constables and soldiers, the front door would be smashed down. Once inside the occupants would be dragged from their beds, and the suspect would be identified, there were many willing to do this. After being identified, the now prisoner would be dragged outside, if they were lucky, taken by post chaise to the Sessions house to be arraigned before the magistrate. There was in fact a reign of terror, even those who had had little to do with the loom breaking felt it prudent to leave the area, many would never return. Soon the towns regular lock ups could not cope, so other secure places were found, mainly public house cellars[2]. In the early hours of the 26th April soldiers and special constables[3], (some of the latter had been paid spies previously) fortified with rum and brandy supplied at public expense, went out into the night, making three arrests in Blackburn, Thomas Leaver, Thomas Dickenson, and William Sutcliffe, one in Livesey, James Irving, and one in Samlesbury, Simeon Wright[4]. The prisoners were held in the Old Bull Hotel on Church-street before being interviewed by the magistrates, Charles Whittaker, a Parson and John Fowden Hindle. After arraignment the men were sent under escort to the House of Correction at Preston for further examination. Isaac Hindle and Richard Entwistle were arrested on the 5th May and dispatched to Lancaster via Preston that day[5]. Edward Houghton who was shot during the Park Place Mill riot was brought by sedan chair to be examined by the magistrates on the 13th May at a cost of 4s[6]. Thomas Brady was paid £2 10s for watching over Houghton for twenty days. Chambers, who had fled to Manchester was taken into custody by the local constable, John Kay was sent to bring him back to Blackburn. John Howarth, shot at Jubilee Mill, once recovered joined the other rioters at Lancaster. The prison regime for those awaiting trial was not very demanding, they were only expected to work if they could not maintain themselves[7]. One thing is certain, they would be better fed than most of than most of them had been for months. A typical day’s food was; a quart of porridge for breakfast, lunch could be either meat stew, boiled beef, or cheese and potatoes, the main meal in the evening would be the same as breakfast. They could attend school, the prison employed a school-master, and there was also a library, though the books were mainly religious. If their clothing was not thought to be up to scratch, this was replaced.

Meanwhile back in Blackburn, a public meeting was called on the 25th May by the town’s vicar, Rev. J.W. Whittaker[8]. A vote of thanks was passed to the magistrates Charles Whittaker and John Fowden Hindle, the High Constable Christopher Hindle and to the 1st Dragoon Guard Officers, Captain Bray and Lieutenant Morris. Strangely there is no mention of John Kay or his deputies. By June the bills for the damage were coming in. The charge to the Blackburn Hundred was £13,960 5s[9]. Every township had to contribute, Blackburn’s bill was £1,891 4s, by far the largest.

Food Distributed during the week ending 3rd June in the town was as follows[10];

Oat Meal………… 25,440 lb.

Bacon………………2,461 lb.

East India Rice …….2,576 lb.

Trade it was said was getting better, but there were still many out of work. Time must by now be dragging for those awaiting trial.

On the morning of the 8th August 1826[11] the judges who would preside over the Assizes were met at the county boundary with Westmoreland, they had had a very quiet time in Appleby as no cases had been presented. The High Sheriff with large numbers of local gentry and an escort, not only of retainers with javelins, but a troop of local Yeomanry attended the justice’s, Sir James Alan Park and Sir John Hullock. They arrived in Lancaster just before eight in the evening, going directly to the Castle. There, before a crowded court the Commission was opened. A short time later the court was adjourned until the following morning. On the following morning, Wednesday 9th August the judges left their lodgings just below the Castle and walked in procession to the Parish Church alongside the Castle. Here they attended Divine Service, after which Justice Park went to the Crown Court and there the Grand Jury was sworn in. It was this jury that examined the cases before the Assizes to see if they should be proceeded with. The foreman was Lord Stanley and members were drawn from the gentry of the county. Justice Park then addressed them. He said how disappointed he was that there were so many cases before the court. Coming to the cases of the loom breakers, he said; “One class of cases gives me and must have given you infinite concern. No fewer than sixty-six prisoners (including 22 relating to Blackburn) are charged with rioting and destruction of property. There was an act of his late majesty (52 Geo III) ‘that if any person shall unlawfully, and riotously demolish or bring into danger any machinery he should be guilty of a capital offence.” However painful it might be to them yet he feared that they would feel it their duty to find many bills for the capital charge yet he would hope that they might feel that they had discharged their duty by finding some bills for a misdemeanour only, which he trusted would be the case. After talking for some time on the other cases he returned to the rioters, saying, he had forgotten to mention that in the case of the rioters it was not necessary that every hand should have committed an act, it was sufficient that the parties were present when rioting took place. The Grand Jury took the best part of two days before retuning “True Bills” in the cases of the rioters; they could now be tried by a petty jury.

Sir James Alan Park was of Scottish birth but had been brought up in England, married to Lucy Appleton from Preston. In 1791 he was appointed Vice Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster, he was the Attorney General for the county at the Luddite riots and had been instrumental in the severe sentences handed out, eight men were hanged. At the Salisbury Assizes of the summer of 1818, having passed sentence of 18 months imprisonment on William Hopwood for stealing a sack of oats, he changed this to seven years transportation as a result of some remark made by the prisoner. This then was the man who was to preside over the fate of the loom breakers.

The first of the trials of persons involved in the Blackburn riots took place on Monday the 14th August. James Riding, William Sutcliffe, Richard Kay, James Latham, James Ormerod, James Howarth, and Thomas Bolton were charged with riotously assembling and destroying power looms at the factory of Messrs Eccles and Co. The prisoners entered pleas of “Not Guilty.” Mr Starkie opened the case for the prosecution, giving in general terms, an explanation of the differences between hand, and power loom weaving to the court. John Kay was called; he gave an account of what happened, as did the Rev Richard Noble, and Eccles Shorrock, one of the partners of the mill.

Other witnesses were called, John Morten, a deputy constable had seen James Riding. Henry Hilton, a barber, had seen William Sutcliffe in the factory yard, but had not seen him breaking looms. The next witness, George Colburn, had climbed on the roof of the mill when the mob had arrived, but had seen Richard Kay in a room below and had heard Kay say that he would not work at the mill anymore. Betty Longworth saw James Latham and James Ormerod in the mob that came in the mill; Latham had a hammer in his hand. She also said that Ormerod, on seeing her said he would knock her down, but that she did not see him doing anything. John Morten identified James Howarth, whom he saw get out of a window when the soldiers arrived, he had a large knob stick in his hand. Another witness, Ann Street, said that she had seen Thomas Bolton on the evening of the 24th April and that he told her that he had broken looms at Blackburn and that he was going to break more at Low Moor. The prisoners being called on for their defence denied that they were engaged in the riot. Witnesses were then called to their character. Mr Thomas Bolton spoke for James Riding, having employed him for two years he knew nothing against his character. Edmond Evans had known Riding eight years and had been his neighbour for three years, he was a very decent man. John Kay, the Constable, had known William Sutcliffe some years and never knew anything against him till this charge; Sutcliffe was a butcher and sometime weaver. John Brown, who was a neighbour of John Kay, saw him come out of the mill in the company of Ralph Shorrock just before the mob came. Kay stood with the witness at some distance from the factory during the whole time when the mob were in the mill breaking looms until the soldiers came, the prisoner never quitted him or joined the rioters. This witness, who was a working man, was severely and minutely cross examined to extract some contradiction from him, but nothing decisive was elicited.

On Behalf of James Lathem, John Cunliffe said that he saw Latham in a field behind the mill while the riots were going on and that he did not have a hammer. Thomas Harwood swore that he had seen James Howarth in Ribchester about four o’clock and that as Blackburn was six miles away Haworth could not have been there. Mr Justice Park summed up at some length, and the jury after retiring for some time returned “guilty” verdicts against Riding, Sutcliffe, Kay, Latham, Ormerod, and Howarth. The prosecution gave up the case against Bolton and he was acquitted. The Jury recommended that the convicted be granted mercy, his lordship said; “That this would be attended to.” The prisoners were then removed from the bar without any sentence. Tuesday the 15th of April saw the second trial of those involved at the Jubilee mill. James Chambers, Simon Wright, Thomas Dickinson, and Richard Entwistle were charged as those in the previous case but an additional count charged them with actually breaking and destroying. The prisoner Wright pleaded guilty, but his lordship told him to withdraw this, he then pleaded with the rest “Not Guilty.” The opening statement from the prosecution was much the same as the case before. John Kay recalled seeing Chambers at the gate of the mill, he had known him for twenty years, and he had even got a job for him some months before. Chambers had a hammer in his hand (this was produced) and was shouting; “go on my boys and down with the looms.” Then Dixon Robinson gave evidence. He said that he had seen Chambers waving a hammer, and saying; “Break away, break away my lads, never mind the soldiers.” I saw him later in the factory yard still shouting. I took the hammer from him and gave it to Mr Kay. It was now the turn of the Rev Noble to give evidence. I am a clergyman, and magistrate of this county; I went to Mr Eccles’ mill, there were many thousands there. Simeon Wright was there, he was getting away and ran against me. I never knew him before. There was a stick in his hand, he fell down, and as soon as he got up he aimed a blow at my head, the blow fell on my shoulder, it was a painful blow. I believe he was seized by Mr Dixon Robinson. Mr Robinson being recalled confirmed the Rev Noble's evidence. The next witness was James Holding – I live at the Run Horse in Blackburn. I was at the factory gate and saw Thomas Dickinson amongst those who broke open the gates; he was shouting ‘Stand back, let’s come’. I saw him go into the yard, and then towards the factory, there were many thousands there. The prisoner then said I was not there at all, he never saw me I was at home at work. The witness said I am sure he is the man. I have known him twelve months he usually sells ‘toffee’ (confectionery) about the street. Thomas Cain the next witness said I saw Richard Entwistle there and he was striking the looms with what looked like part of a loom, I only seen him strike at the loom once or twice in the lower rooms. I was in the factory when I saw him do this. John Morten giving evidence stated that he apprehended Entwistle.On the way to the lockup the prisoner said that it was not right to take him without the other two, whom he named. This ended the case for the crown. In his defence Chambers stated that he had been out of work 13 weeks, he was at the factory to get work but all the warps had gone. He went back to look at the rioters. Simeon Wright also states that he also went there as a looker on, he saw the soldiers and was frightened, and was attempting to run away; he did not remember seeing Rev Noble. Thomas Dickenson’s statement was much the same, and Entwistle said he was at Mr Houghton’s, at his work, at the time. Henry Harwood for Chambers said I have known him all his lifetime, and have always found him a very honest man. William Holland confectioner gave Dickinson a good character for honest and sobriety. The prisoner Entwistle called Mr Houghton who owned the Park Place Mill; he gave Entwistle a good reference that he had employed him for three years. Recalling that day he said that he had gone in to town, and that his wife had closed the mill at three on hearing about the riots. Mr Justice Park in summing up called the Jury’s attention to the statute (52 GEO III). His lordship then went through the evidence on its completion the jury retired. The jury having consulted for some time asked the judge to read the evidence against Dickenson again. He did so. The foreman after the jury had, had further deliberation said that they found Dickenson guilty of rioting. His lordship would not accept that verdict, again the jury consulted and returned a guilty verdict, but some of the jury seemed to object, the judge sent them out, they were out for three hours. On their return they found Dickenson not guilty, but returned guilty verdicts for the rest. After the prisoners had been taken down, another batch was arranged. Charged under the same acts, as those tried before were, William Winder, John Haworth, William Charnley and Elizabeth Howarth. The opening evidence was the same as in the previous cases. William Whitehead swore to having seen the prisoner William Winder breaking looms with a wooden roller in the fourth storey of the mill. George Greenshaw foreman to Messrs Eccles also swore to seeing Winder breaking looms. He also saw John Haworth who is a farmer and a man of some property breaking looms with a bar of iron. He left the mill when the soldiers came and was shot in getting over the wall. He was much hurt. This witness was cross-examined by Mr Coltman who was counsel for the accused John Haworth. Joseph Holding and Peter Smith gave the same evidence against Haworth. John Farnhill saw William Charnley in the mill; when one of the doors was broken open I saw him go in. I noticed him because he had lost an arm. Cross examined by Mr Armstrong said I did not see the prisoner do anything. The soldiers came about 10-15 minutes after I saw the accused. When the soldiers came the mischief had been done. I only know him by his having one arm. Reuben Heath also an employee of Eccles’ saw William Charnley in the mill, but did not see him do anything. John Kay the Constable heard the prisoner John Haworth confess that he had been in the mill for a quarter of an hour, witness saw Elizabeth (Betty) Howarth going with the crowd towards the mill. The prisoners being called on for their defence-William Winder said he took no part in the breaking of machinery, Henry Whittaker spoke for Winder as to his character. After other witnesses had testified, the judge summed up and the jury, in a few minutes, found Winder and Howarth guilty and Charnley and Betty Howarth not guilty. This then ended the trials of those involved in the riots at Jubilee Mill. It was now the turn of those who were accused of breaking looms at John Houghton's, Park Place Mill. The first of these were now brought before the court. Into the dock came Thomas Leaver, Isaac Hindle, James Chambers (tried before and convicted) and Thomas Dickenson (tried before and acquitted).They were charged that on the 24th April 1826 they had demolished twenty five engines called power looms at Blackburn, the property of Mr John Houghton. The Crown Council made the opening address, he spoke of the considerable damage done.He would show that Chambers and Dickinson were encouraging and aiding in the work of demolition in spite of the military whom they held in defiance. That they smashed the looms whilst the military were there and fired on them. The rioters had fired before they entered the mill, perhaps as many as a dozen shots. It took from only 5-10 minutes to break the looms; the damage done was to the amount of £150. That there was a riot and that the defendants were involved was proved by Mr Houghton, and other witnesses, particularly Chambers was heard to say the power looms must be broke, or there will be no living for poor people. Witnesses were called, Hindle’s case depended on the evidence of the son of John Houghton some doubt arose over the colour of the coat Hindle was wearing. Mr Justice Park in summing up, said that if the jury were of the opinion that Mr Houghton, if he had got the colour of the coat wrong might he also be mistaken as to the person. Mr Houghton was called and asked about the state of the windows and how far he was from the mill. He said that the windows were not broken and that he was about eight yards distance from the mill. The jury found all the prisoners ‘Guilty’. That ended the trials for the day.

The following morning saw the last trial which involved events in Blackburn, James Grundy, James Leaver and Edward Houghton were indicted for destroying the power looms in the mill of John Houghton.After a short trial Grundy was acquitted, the other two found guilty. Of the other rioters seen about the riots in Blackburn, Thomas Sharples, James Aspin, were both found guilty of offences at Chorley, and Betty Howarth acquitted of her part in the attack on Jubilee Mill, was found guilty of rioting at Helmshore. On the 17th August all the trials of the loom breakers were over. Justice Park thanked the juries, and that after the four days the events must have been as painful to them as they were to him. He feared that some dreadful example must be made as a warning and to put an end to these enormous offences which had been carried out to so great an extent and to teach others in future that if they so offended they would have to undergo some most serious punishment, and perhaps to suffer death. He thought that the trials had been conducted with great fairness. The sentences would be passed on the following Monday; the convicted would have three days to take in what the Judge had said. We cannot wonder how much his words would dwell on their minds over the weekend. On the Monday morning the courtroom was packed.Almost all had come to see the start of an abduction case, but this had to be cancelled due to one of the defendants having left Lancaster. Some women had even taken over the Dock. Justice Park asked them to leave the Dock saying that there were those more guilty than yourselves. The first eleven prisoners were brought up; they included James Chambers, of whom the judge made special mention, saying James Chambers who is the oldest amongst you and the most grievous offender because he has been convicted of two capital felonies and in which he took the most active and riotous part, and also an offence not capital under another statute. It was my intention at one time and I may say for several days to have made him an example by taking his life, but I shall not select him singly on this occasion and therefore I shall transmit his name amongst others for His Majesty’s gracious consideration. But I would not have you to consider that although I transmit this recommendation those who advise His Majesty may not think it necessary to carry the sentence into full effect, but I hope and indeed believe that this will not be the case. Do not however flatter yourselves too strongly that you will escape without very severe punishment. Another motive which has involved me to take the step I have taken is that the respectable juries who have tried you have recommended the first six of you to mercy and that on a ground which is applicable to all the cases – namely the severe pressure of the times. I have nothing more to say but that I earnestly trust that the dreadful example of punishment which is now about to be made and which must be made, though I trust it will not reach the lives of any of you, will convince you that no happiness can result from a life of turbulence and riot, but that peace and good order are at all times conducive to the interest and happiness of men. Judgement and death was then recorded against the sixteen found guilty of offences at Jubilee, and Park Place Mills. In the final outcome three were transported for life, the rest were given prison terms of from three months to eighteen months. Those who were given prison sentences served them at Lancaster, and for those transported to Australia, Hindle and Wright sailed in the Guilford for Sydney on the 31st March 1827;Chambers sailed later arriving in Sydney in 1828 [12]. By this time nearly all those sentenced at the same assize would be out of prison.

Banister Eccles claimed against the Blackburn Hundred at the Quarter Sessions £3178.15.10 for the loss of his 212 looms. The claim was allowed, as was John Houghton's £284.11s.9d for his loss of 25 looms [13]. At the Quarter Sessions held at Preston in October 1826 the chairman T.B. Addison Esq. referred to the trials at Lancaster and made the following statement, “He might now congratulate the country that either from the terrors of the law, or returning good sense in the people no recent cases of the nature of those he had referred to had taken place” [14].

Notes

1. Blackburn Mail, 26th April 1826.

2. Riot, William Turner

3. High Constables Accounts, Lancashire Record Office, GSP 2870/76

4. Blackburn Mail 10th May 1826

5. Blackburn Mail 10th May 1826

6. High Constables Accounts, Lancashire Record Office, GSP 2870/76

7. Lancashire Record Office, Lancaster Castle Papers

8. Blackburn Mail, 31st May 1826

9. Blackburn Mail, 7th June 1826

10. Blackburn Mail, 7th June 1826

11. Court Proceedings – Blackburn Mail 19th-23rd August 1826.

Preston Pilot, 25th August 1826.

Lancaster Gazette, 25th August 1826.

12. Riot, William Turner

13. Annual Register 1826 (Chronicle), Blackburn Mail 30th August 1826.

14. Preston Chronicle, 21st October 1826.

Conclusion

Did the breaking of the power looms make any difference to the lives of the handloom weavers? The short answer has to be no. As a trade they were in terminal decline even before the invention of the power loom. True they hung around for a number of years. Before the power loom was improved they made a living of sorts weaving the better clothes. They were a spent force unable to bring any influence on the trade, not that they had ever been a big influence. The riots in Blackburn were small in relation to others that would come later;1826 was really the old resenting the arrival of the new. There was little change in the living standards of the working class. While the rioters were being tried at Lancaster, the number in the town's workhouse had passed the seven hundred mark, (724 on the 19th August) [1]. Work was being found for some on the construction of new roads, and earnings of 10s.0d to 12s.0d could be earned, but as soon as weaving became available even though the pay was less they went back to it, (6s.0d to 7s.0d), because the labour was too severe for their habits [2]. In the Blackburn Mail of the 12th July 1826, the Darwen weavers called for the introduction of power looms, “to raise the inhabitants from their present state of unexampled distress and misery”. On June 28th The Mail printed a few words from the ‘Roches Inquiry’, “There is nothing to be dreaded from the introduction of the power loom. In India alone a population of 100,000,000 required to be clothed by us”. In a debate on the Corn Laws in the House of Commons on the 1st May, Mr James said, “He must say that any man who died not feel deeply for the frightful distress which now existed in so many parts of the country did not deserve the name Englishman [3]. What if the unfortunate people now suffering were blacks, the House would never hear the end of it. The table would be loaded with petitions”. The Lord Mayor of London on the 2nd May 1826 held a meeting at which the London Manufacturers' Relief Committee was set up [4]. This became by far the largest of the relief funds, and by 15th July had granted to local funds, half of the received monies of £126,575. In September the Government issued surplus army clothing to the distressed areas; Blackburn getting: 360 waist coats, 1320 pairs of trousers, 1340 cloth gaiters, 50 shirts, 320 pairs of stockings, 320 pairs of shoes, 254 great coats, 154 rugs, 560 blankets and 250 flannel waistcoats [5]. Before ending the project I should like to return to the riots. Much mention is made of the military. I had always assumed that the area was swamped with soldiers, in fact there must have been very few at the time of the initial action. Only about sixteen dragoons were sent to Accrington on the morning of the 24th April, even on their return, Captain Bray only took ten dragoons up to the Park Place Mill, yet we are told that there were thousands of rioters [6/7]. That there were soldiers of the 60th Rifles involved is true but no numbers are ever given. A troop of cavalry could be from 25 to 50; we must assume that the troop of the 1st Dragoon Guards was somewhere between. Even if there were a company of 60th Rifles, this would be less than 25. The 1st Dragoons, had fought at Waterloo, they went later under the nickname ‘The Trade Union’ .Was it something they saw those fateful few days that gave them a new understanding of their fellow men? [8]. It was said at the time that the Judge Sir James Allen Park had passed light sentences on the rioters found guilty, and that he had been induced to do so by the manufacturers [9]. Not all of these wanted the power loom, they were well content with the hand loom.It caused them capital outlay to set up a power loom factory, and they could keep costs down by exploiting the hand loom weaver. Knowing Justice Park’s past actions, there could be some credence to this, bearing in mind that one of the rioters actually struck a magistrate (Simeon Wright's attack on the Rev. Noble).That the powers that be were caught out by the suddenness of the riots, and their evident nature, there is no doubt. Yet there had been rumours spreading about the area for months that pikes were being made, and meetings taking place. John Scott giving evidence at the assize in Lancaster, claimed that a signal was hoisted on the hills at Darwen for a week or fortnight before the attacks commenced, and that it was the ringing of a bell in the Methodist church in that place which directed the mob in their work of destruction [10]. Sir Robert Peel the Home Secretary was later to take the magistrates of East Lancashire to task for not informing the Government of these rumours [11]. To show how little impact the riots made here are some points taken from the handloom inquiry held in Blackburn July 1838 [12]. Mr Dewhurst a witness at the inquiry said that there were between 6, to 7,000 handloom weavers within a three-mile circuit of the town. Their wages were in the region of 4s.6d per week;the average wage per cut (20.24 yds long) was 1s-4d. Some weavers could earn 5s in the same time per cut fancy weaving. Rents varied from 1s.4d to 2s.6d according to the number of loom the cottage contained. Mr Banister Eccles one of the board of Guardians in Blackburn said great numbers of weavers applied for relief. The general earnings were from 5s to 6s.6d a week. The board had a rule that they should have 2s.0d a week per head of family, and were relieved in kind nearly up to that amount. Bedding was also given in the winter. Both Jubilee and Park Place Mills are gone, Throp's King St factory is now owned by a pharmaceutical company. Jubilee Mill was badly damaged by fire on 28th October 1842; the site was home for many years to both the Prince’s, and Palace theatres. Park Place was demolished, and its site is part of a shopping complex. Very little is known about either John Houghton or William Throp, but Banister Eccles took an active part in Blackburn civic life [13]. He became a magistrate, and was on the Board of Guardians. Married, he had three daughters, and died in 1842. John Kay was the town’s constable for twenty-five years; he was a butcher by trade. He was assisted by two runners, Thomas Woodhall, and John Morten, who incidentally lived to be over 90. John Fowden Hindle one of the magistrates at the time of the riots, later became Deputy Lieutenant of the county of Lancaster; he died in 1831. I should like to know what happened to Captain Bray of the 1st Dragoon Guards, who seems to have been a most compassionate officer for his time. Perhaps one day! As for the common townsfolk involved in the riots, those who had worked in the mills would almost certainly never work in them again after the riots.

Notes

1. Blackburn Mail, 23rd August 1826.

2. P.P. 1833, 690 VI. Q. 3899.

3. William James, M.P for Carlisle Hansord, 1st May 1826.

4. The Handloom Weaver, Duncan Bythell.

5. Blackburn Mail, 27th September 1826

6. Reports vary from 20 high, to 16 low.

7. Captain Bray’s letter, Blackburn Mail 3rd May 1826.

8. Uniforms of Weapons, The Thin Red Line.

. A Register of Regiments and Corps of the British Army, A Swinson.

9. Blackburn Mail, 3rd May 1826.

10. Preston Pilot, 19th August 1826.

11. The Handloom Weavers, Duncan Bythell, Quoting H.O Papers.

12. Blackburn Mail, 1st August 1838.

13. Blackburn Worthies, George Miller.

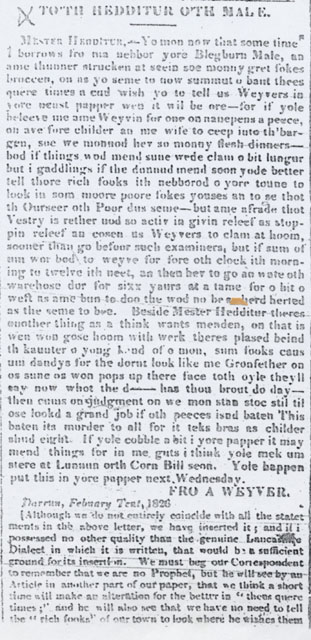

To th' Hedditur O th' Male

Mester Hedditur – Yo mon now that some time I borrows fro ma nebbor yore Blegburn Male, an ame thunner strucken at seein soe monny great fokes broccen, on as yo seme to now summut o bant thees quere times a cud wish yo to tell us Weyvers in yore neust papper wen it will be ore - for if yole beleeve me ame Weyvin for one on nanepens a peace, on ave fore childer an me wife to ceep into th’ bargen, soe we monnod hev so monny fresh dinners - bod if things wod mend sune wede clam o bit lunger but I gaddlings if the dunnod mend soon yode better tell thore rich fooks ith nebborod o yore toune to look in som moore poore fokes youses an to se thot th Ourseer oth Poor das seme - but ame afrade thot Vestry is rether nod so activ in givin releef as stoppin releef an cosen us Weyvers to clam at hoom, sooner than go befoor such examiners, but if sum of um wor bed to weyve for fore toh clock ith morning to twelve ith neet, and then hev to go an wate oth warehouse dor for sixx yaurs at a tame for o bit o weft as ame bun to doo the wod no be so herd herted as the seme to be. Beside Mester Hedditur theres another thing as a think wants menden, on that is wen won gose hoom with werk theres plased beind th kaunter o yong hand of o mon, sum fooks cans um dandys for the dornt look like me Gronfether on os sune os won pops up there face toth oyle they’ll say now whot the d___ has thou brout do day - then coms on judgment on we mon stan stoc stil til ose lookd a grand job if oth peeces isnd baten. This baten its murder to all for it teks bras as childer shud eight. If yole ocbble a bit I yore papper it may mend things for in me guts I think yole mek um stere at Lunnan orth Corn Bill seon. Yole happen put this in yore paper next Wednesday.

Fro A Weyver

Captain Bray. Lieutenant Morris.

Captain George Bray joined the 1st Dragoon Guards in 1825 as a Captain; he resigned, or was retired as a Captain in 1831.

Lieutenant John Bowden Morris joined the Dragoon Guards in 1826; he was promoted to Captain in 18th January 1831, was placed on half-pay as a Captain in 1837 and was still on half-pay in 1840.

1st (The Kings) Regiment of Dragoon Guards (Waterloo)

Scarlet tunics, blue facings, gold lace.

Blue Trousers, scarlet stripe.

Details from Army Lists 1825-1840, Michael Glover, Waterloo to Mans

Dragoons were mounted infantry, who would lead an advance, then dismount to hold key positions in retreat one man in six would hold the horses of his comrades.

Michael Glover, Waterloo to Mans

Most of the information for this project has been taken from newspapers of the day either on microfilm, or hardback:-

Primary Sources

The Blackburn Mail

The Preston Chronicle

The Preston Pilot

The Lancaster Gazette

Salisbury and Winchester Journal

Taunton Courier

Manchester Mercury

Manchester Courier

Cowdrays Manchester Gazette

Wheelers Manchester Chronicle

Hansard 1st May 1826

Calendars of Crown Prisoners QJC*

*Lancashire Record Office, Preston

Secondary Sources

The First Industrial Society, Chris Aspin

The Handloom Weaver, Duncan Bythell

Riot, William Turner

History of Blackburn, W.A.Abram

Blackburn Worthies, George Millar

Annual Register 1826, Chronicle + Law Cases

A History of Lancashire

Cotton Industry of the A.W.A, Edwin Hopwood

Richard Oastler published a letter in 1831 attacking "Yorkshire slavery", and over the next ten years, "Short Time Committees'' were organised in the different towns in Lancashire. Blackburn Short Time Committee invited Richard Oastler to speak at the Theatre Royal, Blackburn on 15 September, 1836.

The magistrates had been very lax in enforcing the Factory Acts, and had dismissed a case brought before them only a few days before Mr. Oastler was due to speak. The same magistrates were in the box at the theatre on the evening of the fifteenth. Mr. Oastler asked if it was true that the case had been dismissed because it was "Mr. Oastler's law". They made no reply, other than laughing at the speaker, who then said: "Your silence convinces me that I have not been misinformed. You say that the law is mine; I say that it is the law of the land which you have sworn to enforce. If you do not regard your oaths, why then it becomes my duty to explain in your hearing how you should stand before the law".

He then went on to say that if they would not enforce the Factory Acts, for the protection of young people, he would show the children how to damage the spindles with knitting needles, and so destroy their employers' property. This line of talk did not win Oastler many sympathisers, but it is not without significance that convictions for breaches of the Factory Acts were more frequent after 1837. John Hornby and Montague Feilden spoke in support in Parliament. William Kenworthy published a pamphlet advocating shorter hours in 1842. He showed that the employers could afford to cut the working day, and that output would probably increase, as well as benefitting the workers by giving them increased leisure time for study and recreation.

A Ten Hour Bill was drawn up, but after the election of 1841, Sir Robert Peel informed supporters of the Bill that his Government was opposed. This was one of the causes that led to a series of riots later in the year 1842. The riots took the form of an attempt to compel the Government to adopt the "people's charter" by an attempted general strike. The plan was to bring the cotton mills to a halt by removing the plugs from the boilers, and thus depriving them of power.

The rioters reached Blackburn on the afternoon of August 15th, and several mills were damaged, and there was a clash between the rioters and soldiers at Jubilee Mill. Although the riots did not bring about the "People's Charter" they convinced the Home Secretary, Sir James Graham, that more factory legislation was needed. In 1844 an Act was passed which limited the hours at which women and children could be employed, and starting the half time system for children, which meant that children in the cotton mills had a full half day for education, alternately in the morning and the afternoon.

By J. S. Miller

back to top