Introduction

A short while ago I decided to write an article on Blackburn in the eighteenth century. The task was to be more difficult than I first envisaged. This period in the history of the town is a difficult one, there is very little written down. Abram mentions the eighteenth century in his book “The History of Blackburn” as does G.C. Miller in “Blackburn, The Evolution of a Cotton Town”, and “Bygone Blackburn” (see also Derek Beattie “Blackburn a History”), but these usually talk of events and the gentry of the place and not the town itself. Having searched through books and other material I decided that I could not get enough information to do the sort of article I wanted, however while looking through the newspapers of the late nineteenth century for another project I had in hand, I came across a set of articles written for The Blackburn Times in 1893 by Abram entitled “Blackburn in 1793, Centenary of Blackburn Newspaper Press”. Reading through these it seemed they were ideal for what I wanted. So I decided rather than write my own article I would transcribe these and give it as Abram wrote it. The articles can be a bit heavy in places but they do give a good insight into the town, its streets, alleys and buildings in the 1790’s.

Abram has as his starting point for the articles the year 1793, which was the year The Blackburn Mail, was established in the town. From that time until 1832 Blackburn had only this one newspaper, it is not unfair to say that at this early period of its life the newspaper printed very little about the town itself, concentrating more on news from the Parliament and world affairs with, perhaps adverts relating to the town, and this was to be the case right up into the early nineteenth century.

When reading the articles remember they were written in 1893, so when it refers to so many years ago it means from 1893.

There are four articles with the last one giving a list of people who lived and worked the town at that time, below is the first one. The articles appeared in The Blackburn Times as follows:

Part 1, Saturday July 16th 1893, p.6

Part 2, Saturday July 22nd 1893, p.6

Part 3, Saturday July 29th 1893, p.6

Pary 4, Saturday August 5th, 1893, p.6

Enjoy. I would be delighted to hear any comments you may have, send them to: library@blackburn.gov.ukStephen Smith, Community History Volunteer

A little while ago an old townsman writing in the Blackburn Times expressed a wish that I should write, for publication in this paper some account of the town of Blackburn as it was a hundred years since: and I now attempt to fulfil that request. If it be desired to describe the former state and appearance of a place, the choice of the particular time is open and is usually ruled by the possession of some kind of materials for a description relating to a certain date. There is a special reason why a view of Blackburn in the past, contrasting with Blackburn in the present, should just now be prepared and printed and why the period selected for such a view should be the year 1793. That reason is that this year 1893 is the centenary year of the Blackburn Newspaper Press. The first newspaper printed and published in Blackburn was the Blackburn Mail, and the first issue of that news-sheet appeared on Wednesday, the 29th of May 1793, these articles intended to commemorate the event. The Press does its share in signalising the centenaries, bi-centenaries, and so on, of other and not more important institutions, and it may becomingly celebrate its own centenary here or elsewhere. Blackburn has been without its own newspaper or newspapers during an interval, but a short one, since the origin of the oldest local journal in 1793. A few months elapsed, I think, between the discontinuance of the Blackburn Mail, after an existence of not far from forty years, and the appearance of three other papers which followed each other into the field in quick succession about 61 years ago, in 1832, namely the Blackburn Journal, Blackburn Alfred (which soon changed its name to the Blackburn Standard), and the Blackburn Gazette. The Blackburn Times has its peculiar claim to distinction in the fact that it was the first penny newspaper printed in the town (or in any town in North-East Lancashire), and it will within two years be forty years since this paper inaugurated the cheap Press in the district.

In another article I shall revert to the Blackburn Mail, and mention some things about its form at starting, and as to how it fared in its early years. The difference to a town, in the preservation for posterity of the events and occurrences which constitute its annals, between having its newspapers and being destitute of its own printed chronicle, is marked. Scanty as the items of towns news may be in the local newspaper of a century back, they are acceptable indeed after the almost total blank of the years which went before the establishment of such intelligencers. Of what transpired in Blackburn during, say, fifty years from 1743 to 1793, prior to the commencement of the Blackburn Mail, one can glean from any source only a very small amount of information, compared with the incidents to be gathered respecting Blackburn life in the thirty or thirty five years onward from 1793. Copies of old newspapers, indeed, were kept and bound up into volumes by hardly anybody, except the publisher, who filed his paper regularly and so far as I can learn there is but one nearly complete set of the Blackburn Mail from the first issue remaining, which was the printer’s bound file, and which has fortunately found its way to the public Reference Library of Blackburn. To the first fifty or sixty numbers of the Blackburn Mail I am beholden for a considerable proportion of the data for the account of the Blackburn of 1793 which I have compiled.

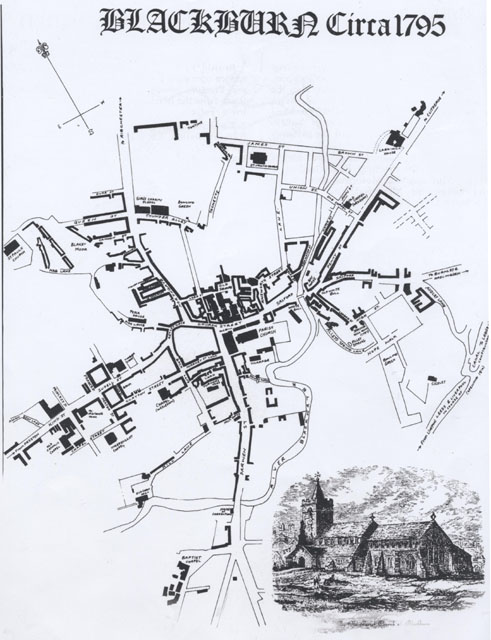

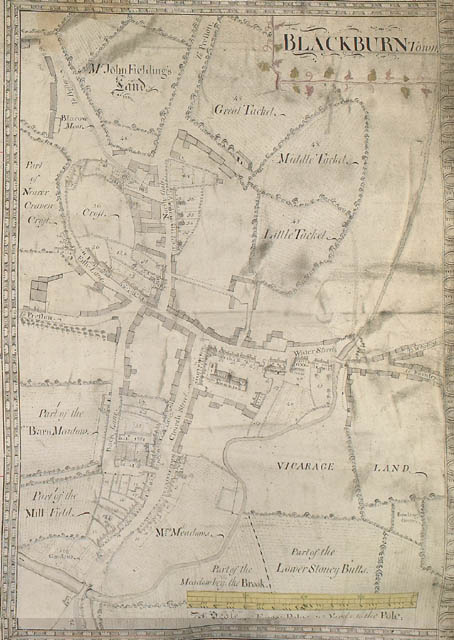

The plan of the town of Blackburn which illustrates the present article represents with tolerable accuracy the streets, lanes, courts, and interspaces of this town in 1793, and also indicates the situation of the public buildings, (churches and chapels chiefly) and principal inns, and detached old houses, the residences of leading townsmen. There is no contemporary map or plan of the whole town of that period. The oldest published map is that of Mr. Gillies, completed in 1822, thirty years later. But with the aid of old plans of several properties near the middle of the town and township, and by means of the knowledge obtained of the portions of the streets and structures built before 1793, Mr M’Callum, the borough Engineer, recently made out a plan upon a good large scale, in accordance with my suggestions of Blackburn in its extent as it stood about 1793 or 1794. The Plan has been reduced from that large one, and engraved for our use in the paper by Messrs. Hare & Co., of London. It will enable the reader to realise better than he could from any verbal description alone the size of the town and the manner in which the buildings constituting it were disposed along or behind its five main thoroughfares, namely, Church-street, in the centre and North-gate, King-street (or Sudell-street as it was formerly named), with Astley-gate connecting it with Church-street and North-gate, Darwen-street, Salford and Penny-street.

The remainder of my space in this introductory article I must occupy by topographical notes on the town of Blackburn in 1793, including its Streets Lanes, Courts, Squares, Crofts, Outlying Hamlets, &c.

Let us begin with a statement, affording an idea of its size that Blackburn a hundred years since was. A Town of about 9,000 inhabitants, but not more than perhaps 7,000 of them would be domiciled in the closely-built portions of the town itself; the balance lived in the detached hamlets scattered over the area of the township at distance of from less than half a mile to more than a mile from what was considered the town. The town of Clitheroe as we know it was larger by a couple of thousands in population, and probably covers considerably more ground than Blackburn in1793. But Clitheroe has its castle in the midst to dignify it, and Blackburn has no such feature. As surveyed from their heights around from Whinney Edge or the top of Brandy House Brow on the south-east, from Revidge on the north or Billinge Hill on the north-west, it would present the appearance of a collection of tenements, mostly built of red brick surrounding an old church; and from that compact nucleus straggling on the lines of the roads which branched from the town in different directions. The length of the town east and west from Salford to King-street and, somewhere on this side of the bridge over the brook at Whalley Banks, might be three quarters of a mile and the breadth north and south from the top of Northgate to the bridge at the bottom of Darwen-street about half a mile. There was a good deal of open ground in the angles between these four main streets; there being no cross streets directly leading from one chief thoroughfare to another. The older portions of the town where the buildings stood thick upon the ground were Church-street, and the blocks of property projected behind that street to the northward, as far as Lord-street and the old Square between North-gate and Holme-street, near the Blakewater brook. These properties were chiefly workshops and warehouses, at the rear of the houses, shops and other places of business fronting to Church-street, to which they were respectively attached. Narrow alleys afforded passage between these back buildings, but only one of these has been left by the modern improvements and street openings (King William-street, Thwates’s Arcade, and Victoria-street); I refer to the passage from Church-street through Shorrock Fold, to Lord-street. Shorrock Fold is itself one of the ancient courts of Church-street, once flanked by two old taverns, the “Star” and the “Black Lion.” The present buildings on the west side of the passage are considerably older than the century. The “Old Square” opened out at the lower end of Lord-street, and was surrounded on the west, north, and east sides by brick houses, which must have been erected before 1793. At the north east angle of the Old Square was a passage extended towards the “Tackets,” an ancient footway between hedges or walls, terminating at the north end, at the foot of Richmond hill—a Cul de sac of Tenements, the name given to the site of which was at a later date given to Richmond terrace when it was opened out, west of Richmond hill. From the middle of the way known as “Tackets,” branched on the west side, “Thunder Alley,” which opened at the other end into Northgate, and gave communication by Queen-street to the lower corner of Blakey Moor. Thunder Alley existed before 1745, for in that year a building was erected for a private house at the corner of Northgate and Thunder Alley, and extending some thirty yards on the south side of Thunder Alley, which for not less than 100 years has been an inn with the sign of the “Masons’ Arms.” On the opposite side of Thunder Alley, the girls’ Charity School, and the house for the mistress were built in 1764. The National School too was erected in Thunder Alley towards the end of the century. For more than thirty years this street has been renamed Town Hall-street, but the old natives still think of it as “Thunder Alley”

Returning to the vicinity of Church-street, our plan of Blackburn in 1793 shows, separated from the “old Square” by two blocks of houses, a court of irregular shape dignified by the name of “Haworth Square.” It was reached from the outer bend of Ainsworth-street and had no other exit except a narrow passage beyond which was the “Bull Meadow,” where, tradition says bulls were baited for popular sport in the days of yore. That field and other enclosures occupied the whole space between “Tackets” and a lane but recently opened in 1793, continuing Ainsworth-street north to join James-street, then also a new street beginning to be built up on the north side. St. John’s Church and churchyard, erected and laid out four years previously, occupied (as marked on the plan) the angle between James-street and the lane going down to Ainsworth-street, which, until not long prior to 1793 was but a very short street starting from the bottom of Church-street and curving round to join with Holme-street at the other end. The lane shown on our plan, which had recently been opened and odd buildings erected on either side of as far as Union-street, abutted upon garden-grounds, occupying both banks of the Blakewater above Water-street, of a house called Cable House the property and residence of a gentleman named Mr. Joseph Ainsworth. It was after him that Ainsworth-street was named. The two parts of the garden divided by the brook were connected by a rustic bridge. Mr Henry Sudell erected a warehouse—the largest in the town when it was reared—on the side of the lane in extension of Ainsworth-street next to the river, but I am not sure that it was built before 1793; if not it rose very shortly after. It is still standing, and now is Messrs. Smith’s furniture warehouse. The old theatre at the turn of Ainsworth-street did not exist in 1793, nor until 1816.

The Houses in Union-street, with the bridge over the river, and in Old Chapel-street, which extends from Union-street bridge to Penny-street, are of evident age, and some of them no doubt were there in 1793. Union-street at first was laid out for a quiet respectable, residential street in the outskirt of the town in that direction, as were likewise John-street and James-street, opened out about the same time. Old Chapel-street existed rather earlier, for it was named from the first Wesleyan chapel, on the north of the street, original the “Calendar House,” converted into a chapel in 1780, and opened by John Wesley, June 23rd 1781. Water-street runs from Salford-bridge end to Old Chapel-street, and in its lower part it has houses on the east side only; the Blakewater, running on the west side, gave the street its name. The small low tenements of which the street consists are older than a hundred years. The Blackburn Mail office was at the lower end of Water-street, behind the Bay Horse Inn.

Salford Bridge, in 1793 was ancient, and hardily wide enough for two carts, wagons, or coaches to pass each other upon it. The street at either end of the bridge and Eanam higher up, forming the eastward road out of town was named Salford as long back as we can trace the thoroughfare. Its name means the ford of sallows, or willows, which, being descriptive for willow grew beside the brook near the bridge and the ford that must have been used for crossing when as yet there was no bridge, is an ancient name, and not adopted at second hand, as some might suppose, from another Salford, on the Irwell near Manchester. Penny-street being at the entrance of the Whalley high road into the town, meeting Salford at the bridge, is an old street, but its line until 100 years since was not so straight as it is now at the Larkhill end where it formerly surmounted the brow more steeply by the natural rise, on a line with a few old tenements not yet pulled down, which stand above the present street on the left. They are the last marked on our plan on that road, just beyond Larkhill House, a large brick mansion, built by Christopher Baron Esq., the then owner of the Larkhill freehold, in 1762. Beyond Larkhill there were, in 1793, no more houses on the Whalley Road, except the farmstead at Derrikins, a little of the road, where Hornby’s mill now stand until Cob Wall was reached.

Between Penny Street and Salford, at the time of our survey, there were no streets; only old structures forming the backs of property fronting to these main avenues. The streets which cover that portion of the Vicar’s Glebe land, named Vicar street, Starkie-street, (after Vicar Starkie), Cleaver-street, Syke-street and Moor-street, shabby and dilapidated as they now look were not constructed far from ten to fifteen years after 1793. South of Salford, I should mention the brick tenements demolished a few years since to open High-street to Station-road, and some others still standing existed a hundred years since, and occupied ground from Salford-bridge to Spring Gardens, at the side of Hallows Springs-lane, as well as on both sides of Calendar-street. Anderton’s Factory, the oldest in the heart of the town, stood on Spring Hill, just above the ancient town’s wells called Hallows Springs; this building has hitherto escaped destruction. The Blackburn Subscription Bowling Green, in 1793 occupied it original situation amongst gardens above Hallows Springs, and at the foot of the steep bank where stood the Tenement with the singular name of Cicely Hole. The construction of the canal along the contour of the same bank was then about to be commenced. It had been planned more than twenty years previously. Audley Lane was an occupation road from the high road at the upper end of Salford to Audley Hall, the ancient farm house on the Rectory Glebe, good part of a mile from the town.

The old Parish Church, a centaury since stood in its sacred enclosure on the south side of Church-street, within a few feet of the backs of the row of antique houses forming streets seen in the painted picture of “Old Blackburn” at the Free Library. The Church yard, in its original area, extended south of the Church to somewhere about the north line of the position of the new Church, and in it, besides the Church, was the Vicarage and Grammar School. The Blakewater, with a sharp bend, approached the back of the Vicarage. The bed of the river was straightened to its present course when the Church was rebuilt and the Church yard extended.

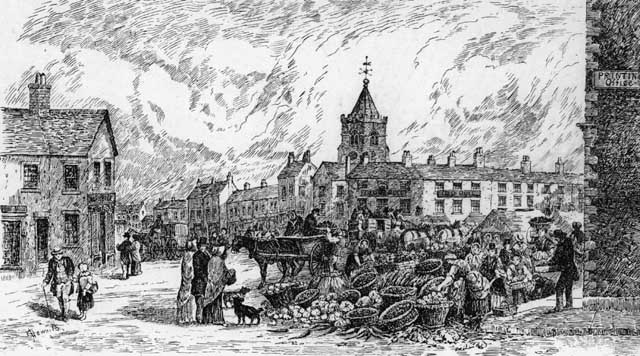

The upper end of Darwen-street, up to the “Cross” at the junction with Church-street, was the old Market Place. That is why Darwen-street was the wide street it always has been. Full half its width was covered with stalls on market days. The oblong block at the top of Darwen-street on the east side between the street and the Church indicated on the Plan, is the Old Black Bull Inn, the most ancient hostelry, and the best accustomed, in 1793. The fall of Darwen-street was much greater formerly than now from the “Cross” to the opening of “Mill Gate,” and beyond to the Ship Inn; then it rose to the centre of the old arched stone bridge. The town may be said to have finished at Darwen-street Bridge, or the block of houses beyond it on the west side. From Darwen-street, Mill Gate, a narrow street, opened to back lane, and continued by Mill Lane, to the water corn-mill on the river banks—a relic of hoary antiquity, for this, no doubt, was the site of the Lord’s “Mill”, of Blackburn Manor, mentioned in charters from 600 to 700 years ago. The Blakewater was dammed by a weir from Darwen-street to the Mill, to furnish water to turn the mill-wheel. Market-street Lane connected Darwen-street and Back-lane, but in 1793 there was no other cross street from Astley Gate to Mill Gate. West of Back-Lane Clayton-street opened, in the roar of King-street, and south of Clayton-street were good sized gardens and crofts. The second Wesleyan Chapel, built in 1785, was in Clayton-street, and the gardens of two or three of the largest houses in King-street were bounded by Clayton-street.

King-street was at first (perhaps 130 to 150 years since) an extension of the town westward, on the Preston Old Road, in order to afford sites, with convenient access to the centre, for more residences of the opulent merchants and people of competent means unconnected with trade. Down to 1793, King-street as a continuous street of buildings, reached not further than the point where a lane from Wensley Fold, called Askew Bent Lane, connected with it, nearly where the modern Montague-street or Branch-road joins King-street. But there were disconnected houses or blocks of two or three, on to Whalley Banks. In another article I shall notice the principal residents in King-street (and other streets) in 1793. Blakewater-street, Heaton-street, and Freckleton-street were formed before that date, branching from King-street on the south; and Chapel-street parallel with King-street, was laid out soon after the Independent Chapel was built on a site there in1778, hence the name of the street. In the angle of King-street and Northgate, fish Lane, starting out of Astley Gate, proceeded a short way, to the house which Mr. Robert Peel dwelt in a few years in the middle of the last century; thence continued as a footway, between thorn hedge, to Blakey Moor, at the upper end of Nab Lane. North of Fish Lane and behind Northgate were the three “Cockcrofts”—“Upper, Middle, and Lower,”—but more like blind alleys than crofts they were and are, what portions of their structures remain. Blakey Moor was reached from Northgate by Cannon-street, Queen-street, and Duke-street. These streets were founded twenty years or more before the end of last century; so that the “Queen” who was thus honoured must have been Caroline, Queen of George the Third, who the “Duke” was who was commemorated by Duke-street, I cannot guess, though one of the Royal dukes of the period is likely to have been intended—maybe the Duke of York. St. Paul’s Church has been built and opened a couple of years before 1793, and is the last building on our Plan to the west ward, past Blakey Moor.

I have used up my space for this week and can barely mention the numerous outlying hamlets, folds, and detached houses which in 1793 dotted the area of the township from the town in the centre to the boundaries. We could not include them in the Plan without making the block take up to large a portion of this page of the paper. One of the hamlets appears in our illustration, namely “Islington,” south of Darwen-street Bridge, a cluster of houses and the old Baptist Chapel (the latter erected in 1764), on the western edge of the “Town’s Moor.” At the opposite end of the “Town’s Moor,” behind the old Workhouse, which was built on a plot appropriated from the moor, lay the hamlet of Grimshaw Park, a group of cottages planted on the slopes of the hill under the stone quarries; and not far off the south-west corner of the Town’s Moor began the more considerable village, as it might be termed of Nova Scotia In 1793, Nova Scotia consisted of rows of houses flanking the highroad, from the Weaver’s Arms to the tenements about Union-street on the other side of the road. West of the town were the hamlet of Snig Brook and Winter-street (the cottages in the latter are some years older than the century) Great and Little Peel, Bent Gap, and Wensley Fold, on the township boundary, which had increased since the first cotton spinning mill in or near Blackburn was built on the brook side close by the ancient “Fold,” in 1777. North-west of the town were Shear Bank Fold, the mansions and farm house at Bank, and groups of cottages at the top of Dukes Brow, on Revidge; and on the other slope, Beardwood, consisting of several old cottages besides the farm house at Beardwood Fold. North of the town, on the road to Ribchester, starting from the end of Northgate, were the hamlets of Limbrick, Little London with Stid Fold and Card Fold, Hole i’ th' Wall, and Pleckgate at the township boundary. North-eastward, on the Whalley Old Road, at the bridge over the brook, was the hamlet of Cob Wall. Eastward, on the Burnley Old Road, past Eanam, were the hamlets of Copy Nook, Bottomgate, Furthergate, and Whitebirk on the boundary of the township. All these names are preserved, but they now belong to populous suburbs of the town, which has spread until it has embraced all of them, except Pleckgate and Beardwood, that are still outlying.

Part of the Glebe Map of Blackburn of 1753. Notice that what is now Darwen street was then called Church street. [By kind permission of The Trustees of Lambeth Palace Library]

DOCUMENTARY ILLUSTRATIONS OF THE TOPOGRAPHY; DOCTOR AIKIN'S DESCRIPTION; MARKETS, TRADES AND MECHANICAL INDUSTRIES &c.

Before going on to describe the markets, principal trades and industries, mercantile and banking establishments &c., of Blackburn town as they existed a hundred years since, it might be of interest to add an item or two illustrating its street plan and general topography in the latter end of the eighteenth century, which was dealt with in my first article printed in the Blackburn Times of last week.

From two old title-deeds, dated respectively 1772 and1780, I extract a few lines in which mention is made of certain streets, lanes and tenements in the town. That they were as described at the dates named is proof of their existence a few years later in 1793, and some of them had not changed tenants. In 1772, a dwelling-house, &c., situate in the street called Northgate, within Blackburn, in the holding of Thomas Haworth; other dwelling-houses in Northgate, in the holding of Margaret Bleasdale, widow. Other dwelling-houses situate in a street called Water-street, within Blackburn, with a barn outbuilding thereto belonging, situate in the Back Lane and several closes of land known by the names of nearer Askew Bent the further Askew Bent, the Black Hole, the Askew Bent Lane, the Larkfield, the Brookhouse, Lark-hill, the Wheat field, and the Little Mosses, in the holding of James Barlow, Innkeeper. A dwelling situate in Water-street the holding of Robert Ainsworth. A close of land called the Croft, in the holding of Mr Thomas Livesey.

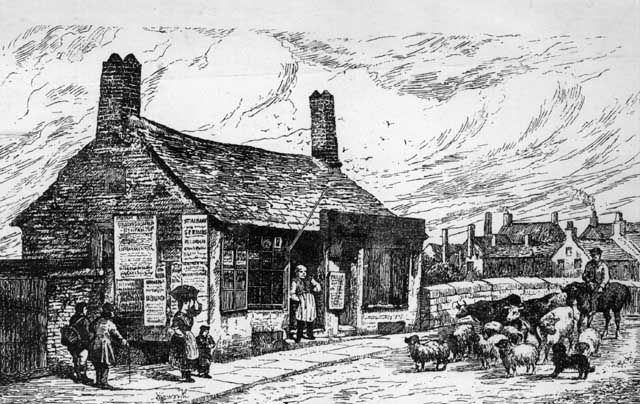

Site of Peel homestead, Fish Lane. Now known as Cardwell Place, the ancient Jacobean farmhouse was tenanted by the first Robert Peel about 1750. Here his son the famous statesman was born and here he made his first experiments in block printing.

In 1780—A dwelling-house, with the barn and stable, situate in and leading to the (old) Square in Blackburn, in the holding of Mr James Barlow, senr.; the beer house, garden, milk house, &c., at the south side of the road leading into (Old) Square, owned and occupied by Mr. Thomas Smalley; and the close of land and garden lying at the back of the same Square in the tenure of John Livesey Esq., A dwelling-house, shop, and beer house, situate in Northgate-street, in the tenure of Thomas Rae, linen draper. A dwelling-house, with the shop underneath, situate in Church-street, in the tenure of Mr. Thomas Holme. A Field, called the Brickfield, situate on the north side of the road from Blackburn to Clitheroe, in the tenure of Lawrence Whitaker, and another field held by the same tenant, on the south side of the same road called the Larkhill situate at the head of a street called penny-street. A field, situate on the north side of a street called Sudell-street (now called King-street), on the east side of Askew Bent Lane.

From another series of deeds dated 1780—A dwelling-house situate at the head of King-street, otherwise called Astley Gate, in Blackburn, adjoining a road leading from the top of Astley Gate into the yard of Mr. Hargreaves. In 1788, the land conveyed for the site of St. John’s Church is named “Tackett Bent.” In a deed dated 1781—A dwelling house, with the back buildings and croft, and the butchers shops and pen-houses adjoining, situated on the west side of a street in Blackburn called Darwen-street, the inheritance and in the possession of John Wareing. In 1779—Sale of a dwelling-house, warehouse, and gardens, situate in the Church-street, Blackburn, lately in the possession of Mr. William Kenyon.

Bank House, Adelaide Terrace from the Haworth drawing, 1888-89

In 1779—Was to let a large and commodious dwelling-house, near the (Old) Market Place, in Blackburn, four stories high, with a garden, house, yard, barn, stables, and shippon in the possession of Mr. Smalley. In 1784—For sale, two freehold messuages, with two large warehouses behind the same, situate in King-street. Also a dwelling-house, shop, &c., situate on the east side of Darwen-street, in the possession of Humphrey Crossdale, Watchmaker. In a deed dated 1788—Two thatched cottages in Fish Lane, which formerly belonged to Esther Hindle; a barn and shippon, a stable, “hovel,” and little garden behind the barn, and several closes and parcels of ground called the Nearer and Further Craven Crofts &c. The owner of these tenements yielded and performed suit of Mill, at the Water Corn Mill of Blackburn Rectory, being one moiety of the manor of Blackburn. In the above extracts are mentioned properties fronting or adjoining the Old Market Place, Church-street, Darwen-street, Back Lane, Astley Gate, King-street (or Sudell-street), Fish Lane, Northgate, Old Square, Water-street, Penny-street, Tackett Bent and Askew Bent Lane; or situate at the hamlets or folds of Brookhouse, Larkhill, Askew Bent, &c.; and standing at different dates a few years preceding 1793. It is from such documentary references that we are able to indicate with certainty the portions of the town built previously to the date named, and to state the Character of the buildings and premises, and who formerly owned and tenanted them.

From another legal document I have met with, two or three material bits of information are obtained respecting the extension of the trade of the town, and the consequent improvement, or projected improvement, of the business, streets and places in the midst of Blackburn. It is a Case for counsel, dated September 1792. The statement of the facts of the Case includes the following particulars—“The Inhabitants of Blackburn, who are become very opulent , have several schemes in contemplation for the Improvement of the Town, and frequently propose different buildings upon the Waste Grounds, regardless of the idea of control from the lords of the manor. In the year 1783, one John Barlow erected a Butcher’s Shop with a room above upon a parcel of Waste Ground adjoining to a rivulet which passes through the town,” &c. “The inhabitants have now [1792] entered into a resolution to alter the (Old) Market Place, and by making an Arch over the River (Blakewater) they mean to form a very commodious situation to make a Meal-house, and to make many other conveniences which will comprise a very considerable part of Waste Ground, and particularly that whereon Barlow’s Building was erected, which they talk of taking down without the least scruples.” The piece of waste ground here referred to would be, I think, situate near Salford Bridge in the direction of Hallows Springs, when it was proposed to create a site for all Town’s Meal-house by arching over the bed of the Blakewater, as was afterwards done. Also it was stated that the Waste Lands near the middle of the township and town were “of considerable value, being well adapted for building ground, yet a clear title to them cannot be made with out an act of Parliament, because the Archbishop (life owner of the Rectory lands) cannot bind his successors; they (the waste grounds) are not object of such importance at present as would induce the lords of the manor to oppose any measure conducive to the interest of the town.

In the bulky quarto, The Description of the Country Round Manchester, by Dr. J. Aikin, published by John Stockdale in 1795, is a short account of Blackburn as it then appeared. The author must have visited this and other portions of the county at least a year or two before his book was written and printed, so that it would be in or very near the year 1793 that Dr. Aikin made on the spot his notes on Blackburn, several sentences of which are worth extracting after a century has elapsed since they were penned. Dr. Aikin wrote;

“The Town of Blackburn is seated in a bottom surrounded with hills. It has long been known as a manufacturing place, but within the memory of man the population was very inconsiderable to what it has lately been. [The memory of a man in 1793 would extend back to 1720 or 30.] It was formerly the centre of the fabrics sent to London for printing, called Blackburn Greys, which are plains [or plain cloths] of linen warp shot with cotton. Since so much of the printing has been done near Manchester, the Blackburn manufacturers have gone more into making of calicoes. The fields around the town are whitened with the materials lying to bleach. The town itself consists of several streets, irregularly laid out, but intermixed with good houses, the consequences [and tokens] of commercial wealth. Besides the Parish Church, there is a newly erected chapel of the establishment, [St. John’s Church], and five places of worship for different persuasions of Dissenters. There is a Free School founded by Queen Elizabeth, and a very good Poor House, with land appropriated to the use of the poor, where cattle may be pastured, [i.e., the Town’s Moor]. Blackburn has a Market on Mondays, but its chief supply of provisions is from Preston [this was so, if at all to a very limited extent], particularly in the articles of butchers’ meat and shelled groats*. The latter are bought by the townspeople about Michaelmas, ground to meal and stowed in arks [large oak meal-chests], where they are trodden down hard, while new and warm, to serve for the year’s bread, which is chiefly oat-cakes. It has an annual fair, on Monday, and a fortnightly fair for cattle.” “Half of the site of this town belongs to the rector, who lets it [the farm land], on leases for 21 years.” “The value of land and price of provisions are increased here within the last 50 years in as great proportion as in most parts of the kingdom. To the east of Blackburn is Foregate [now called Furthergate, but the old people still call the road Foryale], where are some good new buildings.” (I wonder what has become of the good buildings at Furthergate which Dr. Aikin observed as being new when he came. There are no good buildings to be seen thereabouts now, of a century’s age.) “The new road to Haslingden, Bury, and Manchester passes this way. A little to the south is a capital brewery, close by which the new canal from Leeds to Liverpool takes its course.” (it was not then more than just being dug.) “A mile on the Preston (Old) Road is a large printing ground [Mill Hill Print Works] and a factory [at Wensley fold] for spinning cotton twist. On the south of the town lies Hoadley [Audley] Hall, which, with its land, belongs to the Rectory. The land about Blackburn is generally barren and much of it sandy. Coal is found in plenty in the southern end of the parish, and in several parts much stone slate is got, which is used for covering the houses."

Shorrock Fold. An old right of way leading through old Haworth Square towards the Tacketts. There were two inns in the Fold, the Star, used as a lock-up and the Black Lion. The sexton of the parish church formerly resided in the house on the right

© BwD - terms and conditions

These notices by a contemporary topographical writer, who saw the Blackburn of a hundred years ago, and set down those features of the town and its situation which brought his attention, scanty though they be, are of service to us in recalling the town’s salient marks and conspicuous characteristics at that period. After the old Church there were the newly erected houses, warehouses, and gardens of the prosperous merchant manufacturers of the special local textile fabrics; the fields around the town white with the grey calicoes spread out to bleach; the recently erected cotton spinning mill, and the older print works, in the valley, a mile or so below the town; the new brewery; the Canal about to be cut through the township, on the east and south sides of the town; the Poor-house (Old Workhouse), then considered a “very good” one for a provincial town of the size of Blackburn, standing on a corner of the ancient Town Common; the Free Grammar School; the new Chapel-of-ease, Dissenting Chapels, then of recent formation; with an interesting remark on the staple food of the bulk of the town’s people, and their method of storing it for the winter. Dr. Aikin added a table of the number of Christenings, burials, and marriages in Blackburn for the years 1790 to 1795 inclusive, compiled from the Parish Registers. In 1793 the Baptisms were 493; the burials , 400; and the marriages 225; but these figures related to the surrounding rural townships in the parish , whose people came to the Parish Church to christen their children to marry and to bury, as well as the inhabitants of the town of Blackburn.

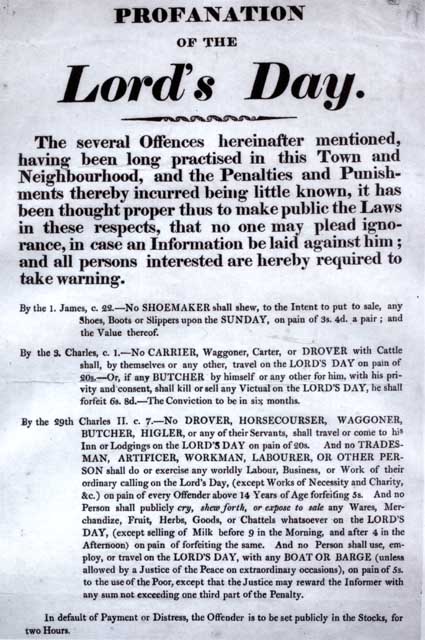

Blackburn was a noted market town hundreds of years ere it became a very populous manufacturing town; and in 1795 it had a large and important weekly market for agricultural produce and other wares, as well as a fortnightly Fair for cattle. Dr. Aikin was, therefore inaccurate in stating that the town was dependent upon Preston for farm produce, The mistake, no doubt, arose from the fact that the greater quantities of such produce came to Blackburn market in 1793 as it does in 1893, from the country districts around and beyond Preston. In fact Dr. Aikin himself says that the same districts, especially the Fylde, supplied Preston market with “great quantities of meat and shelled groats,” one of the two articles he spoke of as coming to Blackburn from Preston. The Blackburn Produce market had undergone about this time a process of severe regulation in order to root out abuses, of forestalling and selling deficient measures, from which it had for years suffered and the townspeople had been aggrieved against the producers who frequented the market. The authorities of the town, supported, by the resident magistrates, had thoroughly overhauled the system of traffic in the market, and had adopted vigorous means to suppress illicit practices found to prevail; and in a short time the market, which had been for a time discredited and prejudiced by the unfair dealings of the farmers out of West Lancashire, recovered its briskness. Mr. Justice Whalley, on several occasions in 1795, interposed to protect the townspeople from extortion and petty frauds in their own market at the hands of vendors of produce coming from a distance. He ordered overlookers of the market to seize and publicly burn all deficient measures of which there were many in use, detected by them in the market and the offenders were prosecuted. The frequent references to these occurrences in short paragraphs published in the Blackburn Mail denote how seriously the matter was regarded by the inhabitants. In a local article which appeared in the Blackburn Mail about the middle of 1795, on the market question and the recent measures to purge it from the abuses to which I have alluded, the writer goes on to review the increase of the town of Blackburn and of its trade and population, during several years preceding that date. The article furnishes an interesting view of the condition and circumstances of the town of Blackburn in the last decade of the eighteenth century. I have estimated the population of the township in 1793 as about 9,000, and it was then increasing at the rate of 400 or 500 a year. The editor of the Blackburn Mail gives the population in1795 as 10,000; I quote the most Material portions of the article as follows;

“The resolutions latterly passed by the Magistrates and Gentlemen of this great manufacturing town, for regulating the Market, have been attended with effects satisfactory both to the seller and buyer; and the Market continues to be plentifully supplied (nearly 80 carts loaded with different kinds of provisions having been at the Market last Wednesday). Blackburn now continues upwards of 10,000 inhabitants, who must be fed daily from supplies of the farmers around.”…”When we take a view of Blackburn some years back, then containing 300 or 600 indifferently built houses, and not more than 3,000 or 4,000 inhabitants, it is matter for surprise and admiration to every well-wisher to its prosperity to know that it now contains not fewer than 6,000 houses, some of which would be an ornament to any city in the kingdom; three Churches, a dissenting (Independent) Meeting-house, a Baptist Preaching house, a Methodist Chapel, a Roman Catholic Chapel, and some 10,000 inhabitants. Some idea of the trade of the town may be formed from the number of wagons constantly employed in bringing wares to and taking them from it. By the list of them lately published for the use of the warehouses, public-houses, and shops, it appears that there are thirteen carriers’ wagons employed in that business, some of which run daily, some once some twice, and others of them three times in the week, to the various towns in the connection, seldom without being fully laden.”

A few weeks later, the Blackburn Mail reported “that the late regulations in our Market continue satisfactory to the frequenters of it, and it is also plentifully supplied at much lower prices than for some time past. Yet there is still a matter calling for redress, much complained of by many as being a great nuisance, which is the permitting the lime-carts immediately in the Market-place; and a correspondent recommends their removal to some more convenient part, the unloading and emptying them in the street proving very injurious, not only to the people who bring their wares to market, but likewise to the private house and shop keepers.”

The Trade in Cotton textile fabrics was a hundred years since, as it is today, the staple or principle trade of Blackburn. But it was carried on, both as a manufacture and a mercantile business, in 1793, under conditions different from those which we are at present time familiar as it is possible to imagine. Although the “Spinning Jenny” of James Hargreaves (a Blackburn man) had been invented and its practical utility proved more than twenty years, and there were many “Jennies” employed for spinning cotton yarn in the Blackburn district, the establishment of factories for cotton spinning had been tardy in this part of Lancashire. Most of the “Jennies” were in the hands of small traders, who set them up, by twos and threes, in such premises as could be secured, and driven by hand or by water power. The great traders of the town had not as yet, embarked in cotton spinning on a large scale. They are not described as cotton spinners, but as “Calico Manufacturers,” “Dealers,” “Chapmen,” or “Merchants.” Strictly, as the word “Manufacturer” is now understood, these old Blackburn calico merchants were not “manufacturers,” any more than they were “spinners.” The peasant weavers were the “manufacturers,” and so often designated then. The dealers were their employers, or masters, who supplied them with warps and wefts, and paid them wages for weaving yarn into cloth. The warehouses of these capitalist traders but partially answered to the mills or factories of their present day successors. In them was stored the cloth, after it came from the weavers and was thence carried in wagons, over the highroads to Manchester, for sale in domestic markets, or to Liverpool for export. The Sudells, the Feildens, the Liveseys, the Boltons, the Hindles, the Yates, the Whalleys, the Thorntons, the Boccocks, the Marklands, the Haworths, the Leylands, the Cardwells, the Birleys, the Chippendales, the Smalleys, the Glovers, the De la Prymes, the Hornbys, and the Mauds, were in the fifty years from say 1760 to 1810, the leading merchants of Blackburn who dealt in the “Blackburn Greys” the checks, and the plain cloths of mixed linen and cotton for bleaching. Collectively they employed some thousands of weavers, but they did not find them looms, or rooms to work in, only materials for the calicoes in the shape of cops of weft and sized twist warps. The warehouses were situate in or behind most of the half-score streets which I have named as constituting the business centre of the town. Some were in the courts at the back of Church-street, and those were amongst the oldest; others were in Fish-lane, Back-lane, Market-street Lane, Clayton-street, Heaton-street, Paradise-street, Duke-street, Lord-street, and Ainsworth-street. Many of these old warehouses remain but they have long since ceased to be filled with warps, weft-skips and piles of grey calicoes. They have been converted into small workshops for minor mechanical trades.

As for the working weavers on the hand-looms, their cottage dwellings were also their “shops,” and, a hundred years ago far more than the weavers employed by the Blackburn master traders in calicoes lived within the compact limits of the town. They were not under any necessity to dwell near the warehouses, visited no oftener than once a week. It was cheaper and healthier to live on the outskirts of Blackburn, or three or four miles of at Mellor, Ramsgreave, Clayton-le-Dale, Salesbury, Billington, Harwood, Knuzden and Stanhill, Belthorn, Lower Darwen, Livesey, or Tockholes. The hand-loom weavers of the period were a more unsophisticated race than the operatives, or mill-hands, who have displaced them, less accustomed to luxury in food or costly materials and showy style in dress; but they had infinitely more personal liberty and choice of working hours, and they could and did gratify their inbred love of field sport on other days than Saturday afternoons. In the town, the living and sleeping rooms of the cottage weavers were extremely small, and lacking in sanitary appliances, but the air around them was little contaminated by smoke, and flowers bloomed in almost every cottage window, and in the little garden plots at front or back of most of them. Their wages fluctuated so much with the ups and downs of the markets for the several kinds of cloths they wove, that whilst at times they lived like fighting cocks, utterly careless of the future, at other seasons, when trade was persistently bad, they were reduced to the lowest state of indigence and distress. One circumstance in which they differed from their decedents, the operatives of our day, was that they extensively wore the grey cotton, the checks, and the calico prints which they helped to produce—the grey calicoes for men’s shirts and female underclothing and for household use and bed-sheets; the checks for aprons as well as for shirts, and the prints for women’s dresses and girls’ frocks—thus contributing to keep going a manufacture which was still mainly one to supply clothing for the people of Great Britain.

I cannot finish in this article the sketch of Blackburn trades and industries a century back; but leave to the next notes of the earliest cotton spinning firms and of trade’s subsidiary to the cotton manufacture carried on at that time; also of iron foundries, the first public brewery in the town and banks existing in 1793.

*Groats are the hulled and crushed grain of oats, wheat, or certain other cereals.

THE EARLIEST COTTON SPINNERS; SPINNING AND CARDING FACTORIES AT WENSLEY FOLD, MILL HILL, EWOOD AND SPRING HILL; CONNECTED TRADES—SIZERS, BLEACHERS, DYERS, REEDMAKERS, &C; THE OLDEST IRON FOUNDRY ; THE GRIMSHAW PARK BREWERY.

The account of the calico manufacturing trade of Blackburn as it was carried on in 1793, which I gave in last week's article, would not be complete without some reference to the two or three cotton spinning factories which had then been built and worked in the town and its vicinity. It would be understood that the old opulent firms of merchant traders in calicoes did not embark in cotton spinning with the new spinning machines invented by Hargreaves and Crompton under the factory system. They were content to pursue their business on the accustomed lines, purchasing the twist and weft they wanted where they could, and being satisfied so long as they could procure it in adequate quantities and good quality. Down to 1793 and for years after, the merchant princes of Blackburn, the Sudells the Hindles, the Feildens, the Cardwells the Birleys &c., none of them owned a spinning mill. Rather strangely it chanced that the first Blackburn man, who ventured his capital in cotton spinning on a considerable scale with the spinning frames newly invented, was not previously connected with the cotton manufacture as a trade, but was a professional gentle man, namely, Dr. Joseph Lancaster. “Physician,” son of Mr John Lancaster of Blackburn, “Apothecary.” I conjecture that Dr. Lancaster must have made the acquaintance of Mr Samuel Crompton, of Bolton, the inventor of the “Spinning Mule,” and have been introduced by his representations of the revolution the spinning machine must effect, to erect a factory, fit it with the novel machines, and start cotton spinning in a bold and enterprising way. The surmise has for its support the fact that Dr. Lancaster’s daughter, Sarah, afterwards married Mr. Samuel Crompton’s son, George Crompton. Dr. Lancaster’s mother, who was a daughter of Mr. Richard Wensley, had inherited from her father a freehold farm on the western border of Blackburn Township, and the hamlet which stood upon it, which was named “Wensley Fold,” after the owner’s family surname. The Blakewater Brook ran at the foot of the hill along the south limit of the freehold, and afforded a stream of water strong enough to turn a water-wheel, and this factory at Wensley Fold, like all the early cotton mills was to be driven by water power. It was not later than the year 1777 that Dr. Lancaster built the original factory on the right bank of the Blakewater at Wensley Fold. This was one of two or three spinning factories established in the district about the same date (Mr Robert Peel’s factory at Altham was another), the starting of which excited the animosity and dread of the hand-spinners, who saw their craft in danger, and resolved to put down the “Spinning Jennies” and water-frames.

In the year 1779 they gathered in a mob, and scoured the country for miles around Blackburn, destroying the spinning frames, and carding engines, and every machine driven by water or horse, whether found in private-houses, small workshops, of factories. Wensley Fold Factory was attacked, and its machinery broken to pieces. After this outbreak of popular resentment, Mr Peel and other users of the “Jennies” and carding engines, emigrated from the district. Dr. Joseph Lancaster stood his ground, and replaced the smashed machines. He carried on the business of cotton spinning about eighteen years and deserved to have made a fortune in it but he didn’t. The Wensley fold Factory was in busy operation in 1793 and a proportion of the cotton yarn used in weaving the Blackburn Calicoes and printing cloths was produced there. Dr. Lancaster was a young man of about thirty-two when he built the factory, and in 1793 he was forty-eight years old. Two years later, in 1795, cotton spinning became depressed and he was compelled to stop. His failure involved the sacrifice of Dr. Lancaster’s reversionary interest in the freehold lands at Wensley Fold, Miles Wife’s Hey, and Galligreaves. In June, 1795, his assignees offered for sale by auction at the Old Bull Inn, Blackburn, “the freehold and leasehold lands, buildings, &c., late the property of Mr Joseph Lancaster.” They were sold in eight lots, described as (1), a commodious dwelling-house, on the west side of Northgate, in Blackburn, with stables and other out buildings, in the possession of Mr Lancaster; (2), a freehold close of land on the west side of the Stone Delph in Wensley Fold estate; (3), the large freehold building five storeys high, at Wensley Fold, used as a factory, with water-wheel, pit wheel, &c.; also the privilege of carrying water thereto (by a sluce) through the “great meadow”; four dwelling-houses at the east end of the factory, and five newly erected cottages, &c.; (4), the reversionary interest of the assignee (Mr Lancaster) expectant on the death of Mrs Sarah Lancaster, widow, aged 74 years, in one half of the messuage and tenement in Wensley Fold consisting of farm house, barn, and 17 acres of land; (5), the reversionary interest of Mr Lancaster in one half of another messuage and Tenement called Miles Wife’s Hey, consisting of farm house, barn, and 10 acres of land; also (6), in a close of meadow ground called Galligreaves Meadow, 31/2 acres; (7), the beneficial interest of Mr Lancaster in three Rectory closes of meadow land lying near Bent Gap and Whalley Banks, 41/2 acres; and, (8), his beneficial interest in a messuage or dwelling- house on the west side of Northgate, and workshop, buildings, gardens, &c., in occupation of William France, brazier. The two latter lots were leasehold of the rectory.

The winding-up of the estate of insolvent traders was a slow process a century ago, as it often is in these days; and I find that the affairs of Dr Lancaster, as a cotton spinner, which were placed in the hands of a commission of bankruptcy in 1795, were not finally disposed of until five years had passed. In July 1800, it was notified that the Commissioners in the bankruptcy of “Joseph Lancaster, Of Blackburn, Physician, Cotton Manufacturer, Dealer, and Chapman,” would meet in December of that year to make a final dividend, Beardsworth, Barlow, and Neville, solicitors. Meanwhile the Wensley Fold Mill had been worked from 1795 to 1797, by Thomas Green, John Watson and James Houlker in partnership, which was dissolved early in the latter year. Dr Joseph Lancaster after his failure continued to practice as a physician in Blackburn until his death. He married, and had a son, John Lancaster, born in 1793, who afterwards became a surgeon, dying unmarried, aged 33, in July 1828. There were also two daughters of the elder Dr Lancaster, namely, Alice, who died unmarried, aged 52, in November, 1832; and Sarah. The latter, eventual heiress to then estate of her grandmother, old Mrs. Sarah Lancaster (who died, aged 84 in 1798), married in 1821, Mr Crompton, and died in childbed of a daughter, christened Sarah Nancy Lancaster Crompton, who was well known to many readers of this paper as the wife of William Irving, Esq., M.D., and who died in January 1891.

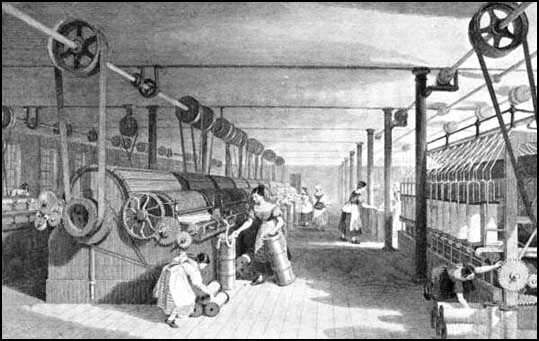

Carding Room

Another cotton spinning factory which had been founded some years before the end of the last century, but has hitherto been overlooked in the historical record of the factory system locally, was one built by the firm of Haworths (kinsmen of the Peels), who carried on for thirty years or more with fluctuating fortunes, as extensive calico printing business at their print-works situated on the bank of the River Darwen at Stakes and Mill Hill, where the Township of Livesey and the Township of Blackburn are bounded by the river. I have unpublished materials for a detailed history of that concern, which existed, with changes of ownership, some seventy years in all, until 1842 (the Turners had possessed the business during the latter half of the time). Here it will suffice to mention that the Haworths, perhaps between 1785 and 1790, added a factory for cotton spinning to their Print-Works at Mill Hill. In the latter end of 1799, the firm were in difficulties, and had to make an assignment for the benefit of their creditors. The three members of the firm at that date were Edmund, John and Jonathan Haworth. The Works were offered for sale by public auction on the 30th of January 1800. One of the properties sold as a separate lot is described as a “capital freehold mill, three storeys high, 33yards long, and 91/2 yards wide, situate near Mill Hill, for Carding, Roving, Drawing, Preparing, and Spinning Cotton Wool by water [i.e., driven by water-power], with two valuable Water-Wheels and gears, 26 Spinning Frames, containing 1,788 spindles, Carding Engines, Drawing Frames, &c., and about 5 acres of land near thereto.” The description is interesting, as showing the machinery of a spinning mill as it stood 93 years ago, and as it was fitted up at least 100 to 110 years since. A factory building, 99ft. long, by 26ft. 6in. wide, and three storeys high holding 26 spinning frames with a total of 1,788 spindles, and a number of carding engines and drawing frames, would be deemed a good-sized one when this Mill Hill cotton factory was erected. Some months previous to the sale of the above factory, in April, 1799, was advertised a sale at Mill Hill of a quantity of cotton yarns, and several Carding engines, “Roving Billies” (as the roving frames were named), &c.

At Ewood, in 1793, a building something like a small factory stood, in which the branches of carding and roving cotton were carried out by James Hitchen and James Barker, under the firm of Hitchen and Barker, described as Carders of Cotton Wool. The partnership was dissolved in 1794, and in August, of that year, was sold “on the premises, at Ewood, near Blackburn, two Carding Engines nearly new, the one double, the other single, one Roving Billy, containing 42 spindles, a Water Wheel, Pit Wheel, and shafts, with the gears belonging thereto.” Also, in November, 1793 a “new Roving Frame, by Boothman and Eccles, of Knowl Green, was on the market.”

Spring Hill House. Formerly the residence of the Anderton family, who built the factory on Spring Hill overlooking the area now known as the Boulevard. Spring Hill cotton factory, erected in 1797, was the second cotton mill to be built in Blackburn, the first being at Wensley Fold. Robert Hopwood, who was manager here before founding one of the largest factories in the town, lived in the house next door. Hallows Spring is in the vicinity.

One other forgotten firm of early Cotton spinners in Blackburn is mentioned in the Blackburn Mail for August 14th 1793. It consisted of three members of one family, and carried on business under the style of “Matthias, Thomas, and Richard Corless, cotton spinners, Blackburn.” I cannot state whereabouts their premises were situate, but I think the building must have been of small dimensions, and probably was an adapted structure. The old factory on Factory-hill, a few yards away from the present Station-road, on the east side, remains as the last vestige of the beginnings of the factory system in the Blackburn cotton trade; for the old spinning factory at Wensley Fold was demolished years ago. Traces are few of the business operations of the builders of that old factory in the town, which, though within a stones throw of the Parish Church was the end of the town in that direction when it was reared. The date of the erection is not exactly fixed, but several years before the end of last century it certainly was going. Mr James Anderton was its builder, tradition says. He and his brothers, who were associated with him in the venture, were not natives of Blackburn, but came, I think from towards Preston; and Mr Samuel Horrocks, of Preston, brother of John Horrocks, the great developer of cotton spinning in Preston, was a partner with the Andertons in the business at Blackburn in 1797. If the local story that the first Robert Hopwood, founder of the Nova Scotia Mills, came to Blackburn from Clitheroe to assist in fitting up the machinery in the Factory Hill Mill, he must have been a very young man on his coming, for he was born in 1773, and the family tradition of the Hopwoods was that he did not settle in Blackburn until about a year 1810. The Andertons, after a few years, gave up cotton spinning, and the factory was transferred to Mr Richard Haworth, who afterwards lived at Factory Hill. Formerly he had been in business as a draper in Northgate. Mr James Anderton, then described as “gentleman,” was living at “Spring Hill,” the older name for Factory Hill in 1824, and at that date, of half-a-dozen firms of cotton spinners and manufacturers in the town, “Richard Haworth, Spring Hill Mill,” was one.

Sir Richard Arkwright, 1732-1792 inventor of the Water Frame

The trades connected with cotton manufacture as it was prosecuted in 1793 included sizing, warping, calico-printing, dyeing, reed making, iron and brass founding, carriers, &c. The sizer’s was a separate and important branch, and there might be half a score of size-houses in or near the town. Mr Henry Sudell had his own size-house, near his warehouse in Ainsworth-street. Other sizers towards the end of last century were Messrs. Birley and Hornby, Brookhouse; Mr Joseph Ainsworth, Old Chapel-street; John Grime, Salford; George Baron; James Towers; and the firm of Astley, Berry, Holloway, and Hopwood. The bleachers were, Mr Thomas Bolton, at Derrikins, succeeded by Mr James Bealey, who was in business there in 1793, upon the site of the largest spinning-mill of Messrs Hornby and Co., still known, I believe, as the Derrikins Mill; the Messrs. Haworth, at Mill Hill, as well as being calico printers and cotton spinners; Mr Richard Bentley, at Whitebirk; Mr John Holme, at Cob Wall; and Mr Hugh Suart at Knuzden. Of several dyers (in 1793) I can name Abraham Bury and James Walkden. The principal reed makers were, Mr Walmsley; William Watson; Mr Procter Ratcliffe; and Messrs. Richard and Thomas Sharples. The leading public carriers of manufactured goods between Blackburn and Manchester, in 1793, were Mr Joseph Wilcock, Mr George Haworth, and Mr John Hargreaves. Powerful teams of horses were needed to carry the goods in capacious wagons by the road over Oswaldtwistle and Haslingdon Moors to bury, then the only highway from this town to Manchester. Mr Henry Astley was the carrier between Blackburn and Preston.

There was a firm of Iron Founders established in Blackburn sometime before 1793. Its members were Mr Richard Crossland and Dr. Joseph Lancaster (the latter was the same gentleman who was a cotton spinner at Wensley Fold). Their foundry was known as the “Blackburn Foundry,” importing that it was the only foundry the town then possessed. Mr Crossland was the partner who had practical knowledge of the business. The partnership endured a few years, and was dissolved in May 1799. Mr Crossland continued the foundry by himself and published this notification:—“Iron Foundry, Blackburn. Richard Crossland, senior, respectfully begs to inform the public that the Iron Foundry business will be carried on at the same place as usual, and hopes, by having a through knowledge of the same, he will be enabled to give entire satisfaction to those who employ him.” Before long he failed, however, and I am sorry to have to add that this pioneer of the iron-founding trade in Blackburn became in his last years so impoverished that he died in Blackburn Workhouse in 1820. If I am not wrong in my conclusion the foundry he started was no other than the old foundry in Nab-lane, later carried on for many years by Mr Robert Railton. In September, 1800 Messrs. George Barnett and son took that foundry, described as “the old-established Iron Foundry, Nab Lane near Blakey Moor,” and announced to the public of Blackburn that they would carry on the business in all its branches and that “all sorts of cast iron work, wrought iron, brass work,” &c., would be executed, as well as all parts of “steam engine work,” so that steam engines were being made in this town 93 years since, if not earlier. Messrs. Barnett likewise recommended “their casting of various kinds of brass utensils used in cotton manufactories.”

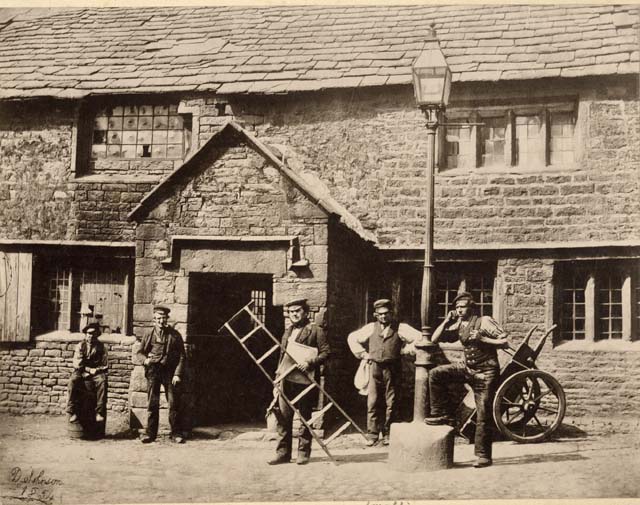

An old picture of Coopers and Brewery Workers (believed to be Dutton's Brewery)

I must refer to a manufacturing business which has since attained vast magnitude in Blackburn that had its genesis in the town just a hundred years back. I mean the production of malt liquor, ale or beer, in a public brewery. The firs brewery was building in 1793, and was completed and got to work, making ale for the townsfolk by wholesale, early 1794. And it was hailed by all classes in the town as a splendid acquisition. The theory was not yet propounded in Blackburn that ale was anything but a wholesome beverage, if properly brewed, with good malt and hops, and I fancy the reason why the New Blackburn Brewery was welcomed was that the innkeepers of the town who brewed their own ale had not given satisfaction in that article to their customers. The brewery was erected on the south-east side of town, at Grimshaw Park. It is noticed by Dr. Aikin as “a capital brewery a little to the south of the town.” The Blackburn New Brewery was opened with circumstance on February 3rd 1794, and in its issue of the Wednesday following the Blackburn Mail wrote on it in the following gratulatory strain—“Monday last the new public Brewery, lately erected at a very great expense near this town, began to work, and the proprietors expect in a reasonable time to be able to convince the inhabitants of the great utility of this concern. Their intended plan of brewing ale of different qualities, to suit every degree of purchasers, must render an essential service to the middling and lower classes of the people; more especially as, from the great conveniences and extensiveness of the Brewery, which is inferior to none in this country, and the capital supply of pure water, with the most judicious brewers and workmen, along with a large supply of every material used in the making of ale being laid in from the best markets, they must be able to sell on very reasonable terms,” &c. The original partners in the brewery were five, of whom all but the first were well-known Townsmen engaged in other avocations. They were, John Nicholls, Peter Ellingthorp, Richard Meanly, William Hewitt, and William Stackhouse. In July 1794, John Nicholls left the concern, and the other four partners kept it going. At the end of about 15 years the Grimshaw Park Brewery began to be supplanted by the Jubilee Brewery, founded 1809, which had no long turn of prosperity, and by the Eanam Brewery of the elder Mr Thwaites, and the Salford brewery of the elder Mr Dutton, both which flourish to this day.

PLACES OF WORSHIP; BANKS; FRIENDLY SOCIETIES; OCCURRENCES IN 1793.

It is needless in this sketch of the town as it was a century back to more than mention the places of worship then existing. Their foundation and annals have been amply recorded, by my self and others, on the occasion of the celebration of their centenaries, and in the History of Blackburn. In 1793 there were two Churches of the Establishment, the Parish Church and St. John’s; one church (St. Paul’s) built by Churchmen, but at first placed under the Countess of Huntingdon’s Connexion; one Baptist, one Independent, one Methodist, and one Roman Catholic chapel. All these congregations are still maintained but only three of the church and chapel fabrics standing in 1793 are left; namely, St. John’s Church, St. Paul’s Church, and the Baptist Chapel at Islington. The Baptist Chapel is the oldest, and is externally unaltered. It is very small and plain—the type of the humble Dissenting meeting house of former times. The Old Parish Church has been re-built; and the independents, Methodists, and Roman Catholics have replaced their original sanctuaries by more spacious and stately fabrics, in Chapel-street, Clayton-street, and St. Alban’s, respectively. The two first-named occupy the same sites as the old chapels; but the first Roman Catholic Chapel, a plain brick building, in a yard between Chapel-street and King-street, is a good mile away from St. Alban’s Church, which is its successor.

Messrs. Cunliffe and Brooks’ Old Bank was founded in 1792, and was in its infancy in 1793. It ranks amongst the two or three oldest businesses in the town, which have endured through the changes of a century. The short, narrow street between King-street and Clayton-street was named Bank-street from the old bank premises in it, which are still there, but the Bank has been removed to the massive and costly building at the junction of Church-street and Darwen-street.

There had been for some years an older Bank in the town, which came to misfortune soon after Mr. Roger Cunliffe and Mr. Samuel brooks opened their Bank. In September, 1793, proceedings were notified of the winding-up of the affairs of the Messrs. John Bailey, Richard Smalley, and William Smalley, of Blackburn, Bankers, who were bankrupt. This firm were also Calico Manufacturers in Blackburn and Manchester, and Warehousemen and Chapmen in Lothbury, London.

Blackburn contained in 1793 no fewer that twenty Friendly Societies, which numbered collectively more than 3,000 members (equal to one-third of the entire population of about 9,000). These Societies, or Clubs, held their meetings in the inns of the town, each having its own house. The members included tradesmen, clerks, mechanics, and working spinners and weavers. The houses and numbers in the clubs were as follows:—King’s Arms Club (100 members); White Horse (99); George and Dragon (120); Lower Sun (90); Higher Sun (94); Bull’s Head (114); Queen’s Head (88); Old Bull (79); Golden Lion (72); Shoulder of Mutton (66); General Wolfe (76); Blackburn Greyhound (32); Wheat Sheaf (98); Anchor (93) ; Weavers’ Arms (160); Swan with two Necks (126); White Bull, Salford (136); Dun Horse (94); Bay Horse (Robert Pickup’s) (84); Bay Horse (Cumpstey’s) (49).

The subjoined items relating to occurrences in the town in 1793 are culled from the numbers of the Blackburn Mail, from the date of the issue of its first number, at the end of May in that year.

1793, May 29. “On Tuesday last, as Thos. Mitchell, a workman in the service of Messrs. Haworth and Smith’s of Mill hill near this town, was attending a water-wheel, his foot slipping, he was unfortunately crushed to death.”

There are now living near this town five persons, brothers and sisters, whose age’s together amount to upwards of 402 years.”

June 5. “Yesterday being his Majesty’s birthday, when he entered the 56th year of his age, it was observed here with ringing of bells and other demonstrations of Joy.”

Potatoes, on our last market day, were sold at the enormous price of 17s. 6d. per load (4 bushels).”

“One night this spring, during the prevalence of the high winds, the centre parts of the walls of the long gallery at Hoghton Tower were blown down.”

June 12. “On Sunday last was plucked, in the garden of Mr. Christopher Eccles, Spring Gardens, in this town, a radish which measured thirty-one inches in length.”

July 17. “It behoves the inhabitants of this town to be very watchful with respect to their property, and careful in securing their doors and windows at night, as there are many in this place at present who have made frequent attempts to break into dwelling-houses here, and several warehouses have also been broken into.”

July 24. “Last Wednesday, Captain Daniel Hoghton, son of Sir Harry Hoghton, M.P., Thomas Parker, Esq., High Sheriff, and other gentlemen, arrived in Blackburn. The bells were rung most of the day; ale was distributed amongst the populace, and a procession, consisting of the principal inhabitants of the town, paraded the street with cockades in their hats, preceded by Captain Hoghton, and attended by an immense concourse of spectators, when several young men enlisted into an independent company which he now raising.”

September 4. The Blackburn Mail announces that so much liberal support has been given to the paper since its commencement (three months previously) that “our impression at the present amounts to nearly One Thousand, which are immediately distributed through this and the neighbouring counties by special messengers, post &c.” The price was 3 1/2. Per copy.

September 11. “On Saturday afternoon, a sheep, given by a gentleman of this town was roasted whole, before a large fire kindled for the purpose in the Market Place, as a present to Captain Hoghton’s company of recruits. A great quantity of ale was distributed to them and the populace.”

October 16. “At our Fair, which commenced on Wednesday last, there was a tolerable show of both fat and lean cattle, the former of which sold very high, but the lean went off rather slowly. There was much woollen cloth, which was generally sold very low.”

“We expect to be able to give an account about this time next year of the spire [tower and cupola] of our commodious and beautiful church of St. John, in Blackburn.”

The Blackburn Mail of November 6th relates that a highway robbery of Elijah Harwood, a Blackburn man had taken place near Mellor; that the dye house of Messrs. Peel, Yates, and Co., in Oswaldtwistle, had been broken into; That the house of a farmer at Stakes, near Blackburn, had been entered by robbers, in the absence of the occupants, and £20 in money taken; and that the shop of Mr. Aspinall, of Great Harwood, had been robbed of several cheeses, and a quantity of sugar, and other groceries. None of the thieves had been secured.

November 20. The Rev. J. Fletcher, of Blackburn, was returning home from Haslingdon, on November 12th, about eight o’clock at night, when “he was attacked, a little on this side of the three-mile stone, by a man on horseback, who attempted to seize his bridle, but was prevented by means of a good stick. Seeing his intent frustrated, he gave a signal, when instantly two men sprang up opposite sided of the road, but being too late to stop Mr. Fletcher, discharged each a pistol after him, happily with no other effect than accelerating the speed of his horse.”

December 11. About the same spot at which the Blackburn clergyman had been waylaid and attacked by footpads as above related, near the third mile-stone from Haslingdon on the road to Blackburn, Thomas Clayton carrier, was similarly attacked on the night of December 5th. One of the footpads seized his horse’s bridle, and another struck him violently on the head but he returned the blow with such effect as to disengage himself and rode of to safety.

December. In the last weeks of 1793, a public subscription was started in Blackburn and other English towns, to send additional winter clothing to the British troops serving against the French in Flanders. In Blackburn a great many of the townspeople contributed and a very handsome fund was raised in the town. Amongst the gifts of the labouring class, it was reported in the Blackburn Mail on Christmas Day (December 25th), that “the workmen at Messrs. Haworth’s and Smith’s calico-printing works at Mill Hill, near this town, have subscribed this week the sum of £3 11s 6d, towards the local fund for providing warm clothing to the soldiers in Flanders.

“On Friday evening, December 27, Mr. Winder had his Ball at our New Assembly Room.” A Better Ball has not been seen here since the days of that once famous master, the late Mr. Bradley.”

A few months onward in 1794 the Blackburn Mail gives the following account of the water supply and Fire-Engine service of the town, which, of course, is as applicable to 1793 as to the year after. First, as to the principal towns well, the Hallows Spring, below Spring Hill, situated just where High-street now crosses the hollow and joins Station Road.; — “There are many little matters of improvement wanting in different parts of the town, which must strike the eye of the discerning. One is, the raising of a suitable arch or covering to the Common [i.e., public] spring, the fountain which supplies the principal part of the town with wholesome water. In its present condition it not only lies exposed to the heating sun and adulterating rains, by both of which the water is rendered less congenial to the taste, and unwholesome, but like wise to the drifting sand and rubbish, which lie over it, in stormy weather. It is needless to point out the small expense such improvement would be attended with. The improvement of Blackfriars-bridge [query—was Salford Bridge then called Blackfriars-bridge?] was a long time shamefully neglected, yet when taken in hand was soon completed, at an expense scarcely observable.”

About the means for extinguishing fires, the Blackburn Mail wrote:—“We are happy to observe that the Fire Engines belonging to the town are duly attended to., being regularly brought out on the first Monday in every second month, when if the least repair is wanted, it is immediately made. The men employed in the exercise of these most useful machines, to the number of 17, properly accounted in their fire caps, &c., have heretofore evinced their expertness, insomuch that , should a fire break out, the inhabitants at present seem to be well protected from any great injury. Such consideration should attract the attention of every person who has property to lose, and as expenses must be incurred, it is no more than common justice to themselves for every inhabitant to join in promoting a subscription for defraying such expense.”