I don't know anything about the Free Lance Journal other than it was printed and published in Manchester for the proprietors by John Beresford, of Stanley Bank, Steven Street, Stratford, and John Havill, of 10, Crescent View, Salford. Their printing works being at 36 Corporation Street and Greenwood Street, Manchester.

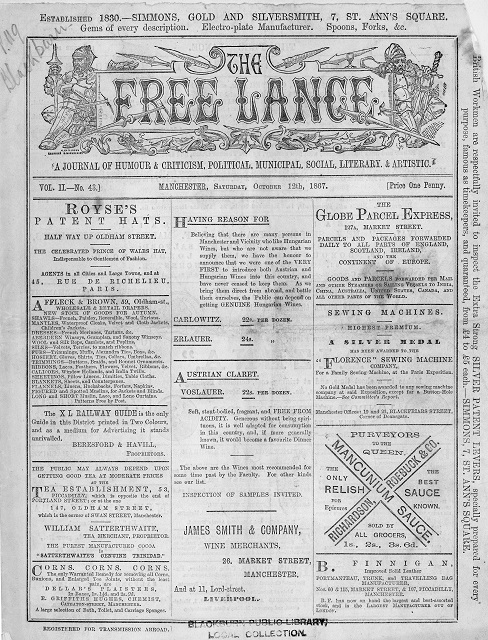

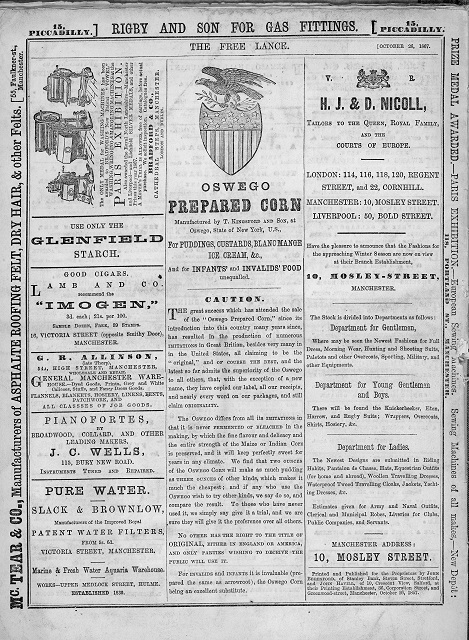

Who the proprietors were or who wrote the articles I don't know. It was advertised as; “A Journal of Humour & Criticism, Political, Municipal, Social, Literary & Artistic", cost one penny and was printed on Saturday. There were plenty of advertisements and articles which included things like “Urban Rambles. Street Sign and Landmarks", and “At Southport in October", most of the articles were local to Manchester. I have included images of the front and back pages of the Journal.

The Free Lance Journal

12th

October 1867

For six months of the year Blackburn stands upon the river Blakewater; for the other six, when there is no water, black or other, in the channel of that stream, it stands upon its merits, or on nothing, which however, is much the same thing. It is an ancient place as is attested by its having given its name to one of the hundreds of the county. Its parish church is nevertheless a modern erection: but the tower of the old edifice has been left standing close beside the new building; partly to manifest the antiquity of the borough and partly in the hope that in case some neighbouring parish wanted a second hand steeple an honest penny might be turned by having one handy. It possesses a Mayor, and the majority of the inhabitants have corporations. It is a rambling, scattered, and dishevelled-looking place: something like the Devilfish in Victor Hugo's novel, it has a compact black centre, and pushes out longer or shorter limbs in every directions. During the last thirty years its increase has been enormous, and as it has increased precisely as anybody chose, mills and cottages being run up anywhere and anyhow, it will be one of the very worst towns in Lancashire to improve into shape. One-third of the entire constituency are keepers of beerhouses, and the aristocracy of the place are the brewers. It is, therefore, needless to state that it is a through-going Tory community. Strong drink is the secret of its own and Britain's greatness; after that its heart has been given for long years to the church and cockfighting. Be sober, lead a reputable life, keep a decent and moderate tongue in your head, and our genuine Blackburner will wax red at the mention of your name and dismiss you as "a ——dissenter." Lead a more or less disorderly life with him for some time until you have wormed yourself into his affections, and then he will offer you the last crucial test of his sincerity by putting you up to "bit of quiet cocking." As this pleasing pastime becomes yearly more dangerous to follow, coursing seems to take its place; and the genuine Blackburner either keeps greyhounds himself or backs those of his neighbours. It is only on such sports and horse-racing that he ever knowingly parts with sixpence without a fair chance of getting sevenpence in return.

Most small towns have a few surnames that seem peculiar to the place and abound in it. Down Matlock way every third person is a Smedley: in Glossop dale Garlicks and Wagstaffes abound: in Bury we have Walkers, Grundys and Openshaws: and in like manner in Blackburn we find a preponderance of Fishes and Eccleses. Now neither of these names is remarkable for its beauty. Fish, is to say the least of it, a scaly kind of surname, and Eccles is suggestive of "cakes:" but the Blackburnese revel in them, and ring the changes on them in a remarkable manner. At any rate they are no snobs. In other localities we have Vavasour Joneses, Norfolk Howards, and every possible orthographical ingenuity to avoid plain Smith. Here we have John Fish, James Fish, Square Fish, Lord Fish, Eccles Fish: Thomas Eccles, Roger Eccles, Fish Eccles: and also Fish Fish and Eccles Eccles.

One of the most noticeable facts in Blackburn is the almost total absence of gentlemen among its people. We use the term gentleman in its purely conventional sense as applying solely to personal appearance, tone of voice, wardrobe, and general bearing and address. In the generality of country towns there are to be found hereditary solicitors, hereditary doctors, old independent families, and trades people long since educated, and who are accomplished gentlemen all over. Not so in Blackburn. There is scarcely a manufacturer, a doctor, or a lawyer the tone of whose voice, whose accent and phraseology, and an indescribable something in the sit of their clothes, do not manifest a certain provincial vulgarity. Gentlemen, in the high and true sense, many of them are, and you quickly discover it: but you would never be surprised if you heard that they were bricksetters or joiners. A few years ago we sat in the semi-private inner bar of the Bull Hotel with a Blackburn friend. Enter a large, thick-set man, slightly grizzled: complexion yellowy green, unsuggestive of soap. He wore a broadish-brimmed hat, apparently fourteen years old, and which had been brushed once a year, and then the wrong way. His clothes, of should-have-been black cloth, looked as though they had been fabricated from second hand stuff originally and cut out and made at home. One cuff was turned up, and showed a wristband that resembled more that of a night-gown than a shirt: and if the hand had been fingering money that day the lucre had unquestionably been filthy. Our friend said:

"Allow me to congratulate you sir."

"Aye, aye," grunted the other.

"May I stand a glass? What shall it be?"

"Gin-culd."

The gin was brought, and he added to it a table-spoonful of water, and then, nodding sulkily to both of us, he jerked out,

"Delth!"

Tossed of the drink, and left the room.

"That's our new Mayor. He was elected this morning" said our friend. On inquiry we found that the new Mayor was a wealthy man and a thoroughly sterling fellow: but conventionally speaking, the man who gets my coals in is a finished gentleman compared to him.

This is all very well to laugh at, but it has its serious side. So long as a town like Blackburn can hardly raise a presentable gentleman to represent it in London, its own due influence and the influence rightly due to the North of England is seriously affected. There is no material for magistrates, deputy-lieutenants, and all the various compliments which government very properly wishes to confer something like pro rata to the wealth and population. Not so long ago a Liberal Government wished to make a few Liberal deputy-lieutenants for the Blackburn Hundred. They applied to the Liberal M.P. He recommended a friend—a most worthy man—but differing in no way, in personal appearances or address, form any mill tackler except that he was broad cloth all the week instead of on Sundays only. He was made D.L., and then ensued a week's fun for Blackburn. The full D.L. uniform was immediately ordered, and a serious of parties given. Our new D.L. was one of our Tory friends "——— dissenters." The parties were serious ones. After prayer and pikelet a request was regularly made that the D.L. should, for the glory of Nonconformity, appear in full costume. This was confined to the borough and was a joke; but after a little while her Majesty held a levee, and our D.L. went up to be presented. If he held himself as if every limb belonged to someone else, as he usually does, her Majesty must have received a remarkable impression of us Lancashire folk. The levee over, the D.L. aired his finery promiscuously about the street of the metropolis, and in the evening saunted down to the House of Commons. He sent his name in to the Liberal M.P.; and meanwhile strutted about the lobby in full uniform, to the intense amusement of all the members. While this was going on, the Tory member arrived. Party spirit ran high then, but patriotism to their common borough ran higher. Giving a hearty nod to the D.L., he rushed into the House, found his colleague and whispered:

"for heavens sake's go out and collar ——, and take him to the nearest lunatic asylum, or we shall neither of us be able to sit here again, he is making such a fool of Blackburn."

These people are among the few remnants of the men who established the trade and erected the larger and older mills from whence issued the multitude of tacklers, cutlookers, weavers, and so forth, who have since filled the suburbs with sheds, and glutted East and West with calicoes. The old race, as a rule, with a dogged determination, a steady unanimity, and an indomitable perseverance, drank themselves to death. Keen as ferrets for the main chance during the day they gave up their evenings to brandy, and, in addition, from three to six times a year solemnly and of malice presence went "on the rant. Hale, strong stalwart men they looked through it all; but when they got to fifty or sixty years suddenly, one fine day, some internal organ snapped, and the establisher of a noted shirting was no more. One of these had an agent in Manchester, who sought the relaxation necessary from trade in a similar spiritual ideal. When the manufacturer was "on the boil the agent looked after the mill and Manchester market as well; when the agent had his turn off duty the manufacturer came almost daily to Manchester; and by these means for years both prospered. At length it happened that they had been stocking goods for a rise, and when the rise came ill-luck both chanced to be "on the rant" at the same time: no one could be found to quote a price for the goods; the opportunity passed and prices fell again. When the manufacturer came round again he went up to Manchester, and said to the agent:

"Now ——, this won't do. One of us must be teetotal, and I've made up my mind it shan't be the gaffer."

The agents mind being equally made up, the consignment was taken elsewhere. Of such stuff were our Manchester men twenty years agone! Who now-a-days would make such a sacrifice for the principle? Of course these drinking, roistering Blackburners of the past were nearly all of them the Cockfighting-Church-and –State-Glorious-Constitution party. The other side were bound by their very profession to lead outwardly sober lives. A greenish complexion was a test of their party and they had their outbursts in serious "muffin-worries" and cockle suppers. And yet there were certainly two of the Liberal nonconforming party who offered themselves up to Alcohol. They were brothers; and one of them performed the Blackburn Happy Dispatch with a persistent torpidity that was absolutely touching. Enter the celebrated Old Bull at any hour of the day, except Tuesday and you would see middle-aged men seated in a corner with a glass of spirits and water before him. A portly man slightly grizzled, with expressionless eyes that had been blue, but not being fast the blue had run into a hazy and milky grey. Not a muscle of the face moved, and not a ray of intelligence came over the calm and vacant eye. Every now and again he raised the glass to his lips, and when it had been empty some little time he knocked the table once with the bottom of the tumbler. Silently the waiter placed another replenished one before him: you never heard him speak, and you could not sit him out. There, with his expressionless eyes fixed on vacancy, he sat for hours, for days, for weeks, for months, almost for years. Round the corner his mill was managing itself as mill will do in such cases. You knew everyone knew, the calm, vacant-eyed soaker himself knew, that it was a race between bankruptcy and the bottle. And the bottle won. One night the doctor was sent for and tried his bottle. It was nowhere: and before the morrow the Old Bull had lost a good customer for ever. We were told that that man had been one of the best read men in the neighbourhood: and possessed refined and gentlemanly instincts. Those sad washed-out eyes, that passive and persistent drinking, have a pathos to our memory to this day.

More vividly tragic was the other's fate. For thirty years he used every faculty nature had given him, and every process unforbidden by the law to make money. Not a gleam of refinement or of delicacy in him. No one could drive a keener bargain or get out of a bad one more craftily. At last he found himself master of several mills and very wealthy. He now determined to enjoy his money, and lo! and behold he could not. He took a large house and furnished it sumptuously. Especially was he great in gilding. Cornice, door-mouldings, chandeliers—wherever gilding could be put—were gilded. The latch-chain to the front door was gilded, and the visitor wiped his foot on a gilded scraper. His wife, and amiable capacious woman (who had she lived would have taken the first prize at old Trafford), ordered silk velvet by the acre. But it all brought no delight to him. He grew weary with the gilt and tired of gazing on half rood of velvet. He disappeared, and in a fortnight returned ill and worn out, and half mechanically resumed the making of that money he had found so bitterly was no use to him. In a little while he would disappear again. This time he would be traced and brought back from some village inn from five to twenty miles away. At another time it would be found that he had never gone a hundred yards away, but had had a ten day's low orgy at his own back-door. And so for months this tragi-comedy of money, gilt, silk velvet and wild, rebellious, drunken protest against it all went on. At length one morning, during the breakfast hour, when all the spindles stood still and the looms were noiseless, he took a quiet ramble through the factory he had created and having asked himself one last dread cui bono? Strung himself up in his engine-house and left his dangling corpse for answer.

We began this paper intending to give a more or less humorous sketch of Blackburn as it is; and we have written rather seriously than otherwise of Blackburn as it isn't, but as it was. And now it is time to end. Some other day, when your Lists are empty, we may perhaps be permitted to break a lighter lance on the Blackburn of today.

back to top

The Free Lance Journal

26th October 1867

We promised to attempt a sketch of Blackburn as it is, but before entering upon that pleasing task we have to discharge a twofold duty—a duty to others and to ourselves—of an apologetic and explanatory nature.

Our last paper had not been many hours before the public ere we were deeply grieved to discover that its concluding portion had given pain to most estimable families in Blackburn and elsewhere, who were convinced that in the subject of those paragraphs they discovered a deceased relative. To them we have to say that had it for one second crossed our minds, ever so slightly, that there were in existence any individuals likely to be so hurt by our picture, no inducement would have been strong enough to have led us to print it. We drew that picture (under circumstances which we will presently explain) without an unkind feeling to any living being, and with no malice to the dead. It ought to have occurred to us that there were people who would be sorely pained by our highly-coloured sketch; but it did not. This thing is done and cannot be obliterated, and nothing remains save to tender our sincerest apologies to the family we have offended. This we now do ex corde atque ex animo.

How that conclusion came to be written we can make clear to our Blackburn friends in a sentence—we were carried away by the fervour of composition. Intimately acquainted as they must be with all the higher and more delicate workings of the human intellect, they will no doubt instantly seize our meaning. For the benefit of less cultivated and less refined readers we may say that with writers of a certain temperament the act of composition commences slowly and calmly, and , after a little while, increases in rapidity and force until a certain intensity of apprehension and vigour of expression comes over the writer, images rise with vivid power upon the mind, and side by side arises also a corresponding strength of words, until, carried away by this glow or fervour of composition, things are put to paper which there was no intention of saying when the writer addressed himself to the task. Such was our case in this matter. Two topics have for years been prominently before us as problems in the study of man as a psychological phenomenon, and as bearing on the civilisation of numerous manufacturing communities which have arisen sp rapidly in Lancashire and Yorkshire. One is: Why men should devote themselves from early morning to late evening, day after day, and year after year, to add pound to pound and factory to factory, and strain every faculty they possess, and employ every means available to pile up wealth they do not know how to spend when they have won it. The other is: What is the rationale of the rush to alcohol as a refuge or a delight? What is the inner reason that impels such numbers of intelligent human beings to seek a permanent solace in steady and habitual "soaking," or drives then into those half-mad bursts of brief and violent intoxication? Is it a physical disease, and rightly dismissed by the doctors as such under the convenient ticket of dipsomania: or is it, that the divine man cannot be wholly buried and that these people, feeling that their round of life was a sordid and unworthy, and lacking light and strength to follow a permanent existence of nobler pursuits and purposes, drown the remonstrant conscience within by steady somnolence of the habitual bottle of the wild excitement of the ten days' "rant?" Filled with such reflections we sat down late at night, to write an article on Blackburn, that without going beyond the exaggeration necessary to a piquant article, should amuse our readers for a column or two. But as we wrote, and person after person rose in our memory, all dead and all self-slaughtered in the prime of life by the cord or knife or the bottle, our thoughts naturally took a more serious and sombre colour, until, when the mysterious hour of midnight chimed from the steeples, the room was literally filled with ghosts. Prominent among their number arose two, and as they illustrated, better than any we recognised, the two problems we have named, the obedient pen fixed them upon paper. For us they had no human surname. They were representatives of a class. They were purely types. They were as much abstractions as the M or N of the Catechism, as devoid of personality as a diagram of Euclid.

And now Blackburn "as it is." In one respect, and in one only, is the Blackburn of to-day inferior to the Blackburn such as we have printed it. The old Blackburner was "game." He prided himself on it, and he practised it. He asked no more from his gamecock than he was prepared to stand in his own person. He wouldn't give a farthing for a cock-fight without "a bit of steel:" and he expected his bird not to wince at a shattered leg or broken wing, but to fight on cheerfully till the end. He, in his turn, was prepared to take "chaff" of the strongest nature cheerfully: he chaffed back again in good-humoured Blackburnese, and if worsted he didn't lose his temper, but stood "glasses round" like a man. Apparently this is all altered: for no sooner did his descendants feel our poor steel-pen, than the whole borough became an upset beehive, and there arose a wild buzz of inarticulate rage over its entire length and breadth, from Snig Brook to Cob Wall, from Brandyhouse Brow to Cemetery. Nor did it rest there. It overflowed to Manchester, and for an entire Market Tuesday the Exchange was filled with irate Blackburners trailing a nonexistent coat-tail with one hand, and grasping an imaginary "Picking-stave" in the other. Perhaps this was inevitable. There are drawbacks and compensations in all things. Given "gameness" you will have coarseness: given a high-polished refinement, and you will have corresponding sensitiveness. And the Blackburn of to-day is not the Blackburn of yesterday. From being a rough and ready, rather drunken and somewhat rowdy town, it has changed into a borough as closely bordering on perfection, as manners and morals, as is compatible with the shortcomings of humanity. Our Blackburn friends will at once call to mind that passage in Bishop Butler's writings wherein he speculates whether a nation may not go mad just as an individual does. Certain it is that an entire town may be "converted" as individuals are said to be. As a drunken collier blackens his wife's eyes at eleven p.m., and at eleven a.m. is a candidate for the Sheffield Hallelujah Band, so did Blackburn—we cannot precisely say when—put off the old Blackburn, and flash forth upon an astonished Lancashire as the manufacturing Athens of the country. Perhaps no better dressed or more suavely courteous specimen of the genuine English gentleman can be found than the Blackburner of to-day. Some slight trace of his native dialect may still cling to him, but it is scarcely noticeable, and in another generation it will have disappeared. A few remnants of the ill-dressed, uncouth citizen of the "unconverted" days may still be found; but they are of the fogy period of life, and are not much seen out of the confines of the borough. But those who actively represent the place here and elsewhere are at once remarkable for their distinguished appearance and gentlemanly address; and when they travel—we have this fact on the best authority, viz.: one of themselves—by guards, fellow-passengers, and folks they meet at hotels, they are generally "tuk fur Loonduners." Our Latin grammar tell us that a taste for polite literature softens manners, and this taste in Blackburn almost assumes that the dimensions of a passion. There are three or four clubs in the town, and in each of these the library is the most striking feature. They vie with one another as to which shall possess the largest numbers and the rarest and most valued editions. Enter them in an evening and you may perhaps find a quiet game for "love" going on in the billiard-room; but you are certain to find the library filled with manufacturers consulting works of standard authority, or perusing the leading Quarterlies in the reading-room. If you are so fortunate as to be able to engage one of them in conversation, you will hear just views on science and art, politics without acerbity, and social views elegantly expressed, than which a more charming intellectual treat can hardly be imagined. In addition to this, we believe that enquiries at Smith's and Mudie's libraries will show that in proportion its population Blackburn takes a supply of the belles lettres in the ratio of 8 to 3 of Manchester. The library tastes of the former Blackburn were satisfied by Bell's Life and Buchan's Domestic Medicine. The change is indeed great. This metamorphosis is the most flagrantly apparent in the almost total cessation of the use of ardent spirits. The Old Bull foresaw the coming "conversion"—hung its tail and in anticipation made itself "limited." We have heard a story of an enterprising policeman—of course this did not occur in Blackburn—who being new to his post and zealous, was placed on a night beat which just embraced the leading hotel. Night after night he caught beerhouse-keepers breaking the law by keeping open after eleven, or permitting disgraceful gambling by allowing carters to toss for gills or factory hands to play dominoes for a penny a game. He speedily acquired the reputation of being an energetic "officer": and then it struck him that if he could only stake higher he might be promoted to the very headship of the force. By eyes applied to the chink of the shutter and keen ears he arrived at a moral certainty that "two off the top" was being played for considerable stakes in the principal hotel. Effecting a quiet entrance he suddenly pounced upon the party, seized stakes and cards as unimpeachable evidence, and took down names of the company, finding, when he laid them before the superintendant, that they were those of county and borough magistrates and members of the corporation. The officer did not rise in the force. If such a thing ever could have occurred in Blackburn—which we doubt—it is clearly impossible now at the Old Bull Limited. There, rational, ordered refreshment reigns. Our own dear Trevelyan is a noisy house compared to it. Its consumption of coffee is something enormous—you rarely see a Blackburn man in it, and if at rare intervals you hear a noisy voice, a rough phrase, or a fescenine story, be sure the culprit is a stranger, and ten to one but some quiet native courteously requests him to be careful lest he should imperil the high character of the community by his conduct. Much as the modern Blackburner loves his library and his quiet home, the desire for health and propinquity of the sea still leads him to spend his week's end at Blackpool with his wife and family. The Incomprehensible and ever varying hugeness of the resistless and unrestive ocean appeals to the lofty nature of the man, and is a well-spring of noble emotions to see him through another week of necessary labour. He goes weekly in the season to the Clifton Arms and spends forty-eight hours in quiet musing by the tide, pointing out to his children how little are all the petty cares of life—weaving sheds and chaffing for yarn—before the everlasting sublimates of creation. This has become quite a by-word at the watering-place. If a party from the south are struck with the appearance of an intelligent, well-dressed man, an elegant better-dressed lady, and a family of refined-looking children, and asks who they are, the answer comes at once, "They are a Blackburn family." And if an invalid seeks for a very quiet hotel, where there is a sedate bar, with the chance of calm and improving conversation, the reply is always, "Go to the Clifton. The Blackburn people go there." That is enough.

Of course, where human nature is, there must be vice of some kind: and there are Blackburners of to-day who are not wholly good. But there are vices and vices; and, as Burke remarks, vice may take such a form as to lose "half it's evil, by losing all its grossness." This is the case with Blackburn. The modern Blackburner who has vicious tastes is no longer the course, ranting, cock-fighting reprobate of former times; he is the polished Lovelace or Mirabel of the past. He is fascinating with the ladies, and if inconstant, why he is only like the gay young knight of the song "he loves and he rides away." As his predecessor in the borough ran close to the law by lying under meal-sacks in an attic while the police made a raid upon a cock-fight, so his more modern fascinating representative has to be wary of breach of promise actions. But if our elegant Lothario cannot marry he never seeks to escape payment; he glories in the cost of his refined amours, and speaks in such delicate and generous terms of the lady he has jilted as to make his very inconstancy seem charming. Virtue is its own reward, says some silly moralist; but in the case of Blackburn it is true. This change in its character has penetrated into its business reputation, and is now bringing golden returns. A few years ago a person giving advice to a young man embarking in the Blackburn trade thus expressed himself:—"If a Blackburn man tells you a thing, simply please yourself whether you believe it. If he finish by saying `That's the truth,` be sure that it is not quite true. If he adds `It's the real truth,` you may be certain it is almost wholly false. If he concluded with emphasis `and that's the real truth—it is for sure,` rely upon it there is no truth in it whatsoever, and that he says it for a purpose." The very opposite is the case now. No Manchester merchant dreams of doubting the word of a Blackburn man. He scorns a written contract. He may have doubt about cloth from Ashton, Glossop, or Chorley, but never about one from Blackburn. During the whole of the recent outcry about mildew, only one piece was traced to Blackburn, and that was proved conclusively to have been rained on. For no Blackburn manufacturer will knowingly deliver a piece that will not enhance his reputation, any more than he would dream of starting a shed without adequate capital. In other localities, unfortunately, concerns are started simply on the gain credit—the cloth being melted long before the gain is due—heads I win tails you lose. No such system obtains in Blackburn; and when in 1864 over 200 manufacturers failed in Lancashire, only one succumbed in Blackburn, and he was not a native.

Of course this improvement has extended to the workpeople. Ten years ago a friend wrote to us in these terms:—"I have seen a Blackburn mill `loose,` and I fancied myself in Gehenna. Some hundreds of children of both sexes, strapping wenches, and awkward shambling men rushed forth with clattering clogs and hideous shouts, like emancipated demons. And as they clattered along, lads and lasses and children, some bawled out profanities and obscenities that made me wince. There seemed no anger in their oaths, no temper in their outrageous coarseness: it seemed the habitual badinage of these light-hearted sons and daughters of toil. If our friend could see a Blackburn mill loose now, how different were the spectacle. No sudden rush, but an orderly exit. Clogs, of course; but no clatter from their measured orderly march. Here, he would see a young man finishing, as he wandered calmly homeward, the penny paper he had devoured by snatches during the day. There, a young woman reading the Tupper or her Mrs. Ellis. Here four young fellows, arm in arm, singing with untutored voices, but in excellent taste and tune, a classic glee: there half-a-dozen lasses pealing forth "There is a land of pure delight," and so to their homes to feed the pet canary or tend the favourite fuchsia or geranium. Later in the evening, if he went into the public park, he would find the same people—cleaned up, rosy and tidy—mixing freely with their masters and their families, the masters giving kindly greeting, and the hands touching cap or dropping curtsey, in no sprit of wretched feudal servility, but as a genuine expressions of the love and kindly feeling existing between employer and employed.

Such is the Blackburn of to-day. It has been quite a pleasure to us to have the privilege of drawing this most inadequate picture: we can only say, O! si sic omnia, and express a hope that as our last paper did not please them, this will. And if any readers at a distance doubt the accuracy of this sketch, we can assure them that "it is the real truth, it is for sure."

back to top