A train set was my dream toy. I spent many happy hours feasting my eyes on train sets in toy shop windows. There were two large stores in Blackburn in the 1950's which had a large toy section. One was in a department store called Nevilles. It had a mock Tudor front and was exciting to enter and visit their toy wonderland, (This can be seen in the photograph of Darwen Street above). The other toy store had an equally large wonderland of toys, it had two shops in the town centre. A large one and a smaller shop near to Neville's.*

There were lots of smaller shops which sold train sets all over town. One shop I enjoyed going to had a presentation in which a model train ran around the shop window display. The shop itself was a model toy making shop. It sold wood and parts for model making. There were lots of construction kits for making signal boxes, stations and trees. There were model tunnels that fitted together. The houses, signal boxes and buildings were paper craft models. I could see the layout in my mind long before it was built and which craft kits I would buy.

During the summer of 1960 my father was involved in a terrible work-related accident. The house he was helping to repair collapsed and he was buried under tons of masonry. He was in hospital the whole summer but eventually recovered and was able to return to work. Compensation was paid out shortly before Christmas 1960.

I think that was my best ever Christmas. The family were able to celebrate this event; Mum, Dad, my brother and me plus the twins which had been born that summer. In my Christmas stocking was a message from dad to say I had a train set for Christmas but I would not be able to have it until early in January. Dad and I talked about the train set. He favoured a Hornby train set but he did tell me about a new company called Tri-ang; this was the Lines brothers' trade mark.

At the time the Hornby sets were made out of metal. The engines looked fine with their diecast bodies. The rolling stock was made out of pressed tin and did not look realistic. The Tri-ang train sets were moulded plastic and looked more realistic. Dad left the selecting to me and I was undecided about which to go for. My friend had a Hornby. I talked to my teacher about the merits of the train makers and it came down to personal choice in the end.

Dad said I could buy the train set from any shop I liked. I visited the toy shops time and time again. One night dad came home from work. He said we would go into town on Saturday to buy it. Later that week I was with friends and we were walking into town. We came across a toy shop I had not seen before and there in the window was the train set I wanted. It was a Tri-ang and now that I'd decided I was not concerned who had made it. That Saturday Dad and I went to the shop and it was bought.

The engine was a model of a Stanier Black 5. It was black with the British Railways insignia on it. The first thing I did was to unscrew the engine body from the chassis and stick small model people in the locomotive cab. There was a driver and fireman. That first time my very own train ran around the track was a wonderful moment. I played all weekend with the wonderful toy. Sunday morning Dad was at the controls; his play lasted half an hour or so then I had it. It soon became hard to tell who was the owner of the train set, Dad or me. He seemed to have a lot of pleasure from it too. I played with it the most.

It was soon fixed to a permanent layout. Mum was secretly horrified that it was kept in the best room and was always in a state of untidiness as new buildings were built and landscaping projects took shape. There were regular services to far distant cities and towns all over the world. How the 11:15 got to France's capital city I will never know. The Chunnel had not been built then, but maybe in my imagination it had. Any way play is magic and all things can happen.

My train set was a mixture of freight and passenger rolling stock. There was a platform near to Fergyville, the village the train served. The houses were a mixture of papercraft kits and the newer plastic kits made by Airfix. I had a lot of fun making the layout. I learnt how to use tools. I learnt a lot about glues and which were the best to use. My tunnel was built to my own design. It was based on Pendle Hill. The tunnel was a long one and took a couple of minutes for the train to travel through it. The board was on the floor. My friend had his in the spare room and it was on a large table.

Tri-ang brought out an innovation. You dropped some liquid down the funnel and the heat from the engine made it smoke. I also had a passenger carriage that lit up and in winter time this was a special moment. I made an electric light from the transformer to the houses in the village. This project taught me about electric circuits. I was having trouble and in a discussion with my teacher he suggested an electrical circuit plan. He drew it for me, I followed the instructions and had the village lit up.

Fergyville was not a peaceful English country scene of the early 1960's. It was a time warp place which was at war. There were many nations the heroic band of 8th army soldiers battled against: Nazi Germany soldiers were a difficult lot to remove. They were always sabotaging the line. The tunnel was a spot that was vulnerable to attack; It would be as I had a piece of track that when you switched points sent the train to its doom.

Engineering disasters took their toll too. I made, on purpose, a flimsy bridge. It looked really strong but there was a piece which fell out of place after the train travelled 20 times around the track. The support would come adrift and the bridge would collapse, sending the 5:10 to Blackpool to its doom.

Wild animals of the giant kind were also a threat to the smooth running of the services. Snowball, the family pet cat would, on occasions, jump the moving train. In scenes of disastrous proportions she would have the train dangling in her paws. It was like watching King Kong terrorising New York. I was not too happy that she should use my train set to improve her mousing skills.

I eventually owned three engines, They were steam engines. One was a shunting engine called Nellie. I thought this was the funniest thing when I saw this little blue engine in a shop; it sort of looked mischievous. One day the Stanier Black 5 broke. I put it in the sidings. It did not take Dad long to realise that of the three engines this was the one not in service. He asked why. I told him it had broken down. Permission was given to take it to the shop for repair. They returned it to Tri-ang who sent it back as good as new.

I spent all my pocket money on my train set. Saturday was pocket money day; I could buy an Airfix construction kit and visit the cinema. The little bit of money left could buy an ice cream and pay for a bus ride home.

These days it's my nephew who gives me model railway pleasure. He developed an interest in trains and model railways. He built layouts based on real railway lines. He developed the interest far beyond mine. At 9 years old he joined a railway preservation society. He helped run the real thing; he was often in the newspapers.

I have fond memories of my train set. It brought me a lot of pleasure. It was eventually given away to a neighbour's small son.

* These shops were Mercer's whose main store was on Northgate. This closed in 2009 after 169 years in Blackburn, but a smaller version of it was opened on Darwen Street, that to as now closed.

A Breezy chat with an Old Blackburnian

From the Blackburn Weekly Telegraph of May 28th 1910

There are not many persons who can say today that they have lived to see six different occupants of the throne of England. To have done so, of course, implies an advanced age, for among the reigns of the last English monarchs is to be numbered the record of one Queen Victoria who herself ruled over the British dominions for sixty-four years—a period which in itself is little short of the average duration of human life. Amongst the few who since the accession of George V have been living under their sixth monarch of England is Mr. Zachariah Smalley, of 215, Accrington-road, Blackburn. Mr Smalley is in his 92nd year, having been born in October, 1818, two years before George III died. He has thus lived in the reigns of George III, George IV, William IV, Victoria, Edward VII, and now George V During all that period, too he has lived within three miles of the borough of Blackburn. His long life may be measured by other standards than that of Royal reigns. He has seen Blackburn develop from what was once a comparatively small and quiet country town into a place of swarming industries and activities; he has seen the cotton industry grow from its primitive existence in the cottages of the hand-loom weavers into a trade upon which many thousands of people depend for their livelihood, and which supplies the demands of the uttermost parts of the world; he has seen the town grow and spread year by year until the peaceful, pleasant fields in which he walked in as a boy have long since been covered by the roaring mills and workshops and the streets and houses of an ever expanding population; he has lived through the transition of Lancashire from a county of agriculture to a county of industrialism, through a period in which mechanism and machinery have utterly revolutionised the conditions of industry and life in all aspects. No period in the history of England, of a similar duration, shows more stupendous and momentous changes than does the last ninety or hundred years, and it comes with something of a shock to find that all the vast alterations between Blackburn as it was in the early years of the 19th century and Blackburn as it is today has been encompassed within the period of a single human life.

Mr. Smalley is Lancashire bred and born. He has the Lancashire simplicity of character, free from the slightest tinge of affectation, the Lancashire good humour and good fellowship, and the Lancashire tongue, too, with its broad vowel sounds and expressive phrases. A most interesting conversationalist, he loves a talk about old days, and fine it is to hear him recalling the incidents of his early life, and bringing back again the reminiscences of what is now a nearly forgotten day. Naturally, he feels his advanced age somewhat, but for all that, he still enjoys a short walk, while his mental facilities are unimpaired. He recalls incidents and dates of seventy and eighty years ago with remarkable accuracy. During the latter part of his life he lived for fifteen years alone at Guide, and up to the age of 89 regularly made a weekly journey on foot to Blackburn market, while when within only a few years of ninety, he walked from Guide to the summit of the Jubilee Tower on Darwen moors and back. Even now, both physically and mentally, Mr. Smalley is as alert and active as men very many years is junior. His thoughts and his outlook upon life, too, are touched with a fine and gentle toleration. He is, indeed a, “fine old English gentleman.”

He was born at a farm known as “Feather bed” in Little Harwood. His father died when he was seven years of age, leaving his mother and twelve children to care and fend for. Soon the family left the Little Harwood district. Zachariah became a bobbin winder at the age of five. In later life he went to live in the Guide district, where he resided for 75 or 76 years. In his declining years he has found a home with his married daughter, Mrs. Holden, of 215 Accrington Road.

The story of the early years of Mr. Smalley’s life is one of constant struggle and hardship. “Aw wor a bobbin winder for a handloom weyver at five years of age,” he said, “me and mi brother, two years owder. But handloom weyven’ kept gooin deawn and deawn. They used to tek their pieces to a wareheawse i’ Blackburn, and sometimes pieces wod be three pence less if trade wer bad. Aw’ve heeard mi mother tell o’ mi feyther bein wod they co’ed a two yard weyver—thad meons as he wove pieces 72 inches i’ width. Aw’ve heard mi mother say he could get 29s a piece an’ he wod weyve two pieces in a week. Bud trade kept gooin’ deawn and deawn. Cloth as aw’ve woven used to be 5s for a piece of 24 inches i’ width. Bud it come deawn at last varra low. Aw wove two or three warps misel at 1s 2d a piece.

“Well, yo’ know, aw geet wed and aw went to t’ mill at lower Darren—Eccles’s. Thad wer t’ fost place as aw warked at i’ a mill. Aw geet abeawt 11s or 12s a week, an’ yo’ know there wor five to keep eawt o’ that. Heaw dud aw wark? Well, we used to start at six i’ morning and wark till hafe past seven at neet. On t’ Setterday we sterted at hafe past five and finished at hafe past three. An’ we hedn’t a full heawr or a full hafe heawr for nayther breakfast nor dinner i’ them days.”

“Those would be hard times,” interpolated the listener.

“Aye. Bud they dudn’t live then like they do now. Milk and parritch [porridge], Thad wer o’. An’ happen them as went to t’ factory wud hev a sup o’ tay in th’ morning.

“When Handloom weyving kept gooin’ so bad, yo’ couldn’t get much. We’d ged a warp and id wodn’t be sized fit to weyve. We couldn’t weyve ‘em beawt sizing ‘em ageon. Aw once paid four pence for a peawnd o’ flour for size. Aw’ve sin flour 3½ peawnds for a shilling mony a time. Sugar, aw’ve paid eight pence and nine pence a peawnd for. An’ sich like food as thad wer dear. Butter wor t’ cheapest o’ ony sort o’ food. Tay—well, yo couldn’t buy nooan under two ounce for nine pence for long enough. Then id’ began coming deawn a bit. A mon come a-living wheer t’ Owd Bank is neaw, name o’ Clemesha. When he come he started selling two ounce for 7½d, bud thad wor 5s a peawnd yo’ know. Bud then there worn’t as much tay drinking thaen as wod there is neaw.”

Mr Smalley went on to tell other struggles of his early life—how “things being varra bad at weyving,” and not being able to earn sufficient money to keep his home going, he started work at the reservoir, then under construction at Guide. “Bud thad wer’ welly as bad as gooin’ to t’ factory,” he added. Then along with some companions, he went to Chorley to similar employment, and afterwards worked for the better part of two years at a quarry in Rossendale, The wages he earned at Chorley and Rossendale were 2s 8d a day. He returned to weaving for a time, and then took a small farm, where he lived altogether for eighteen years.

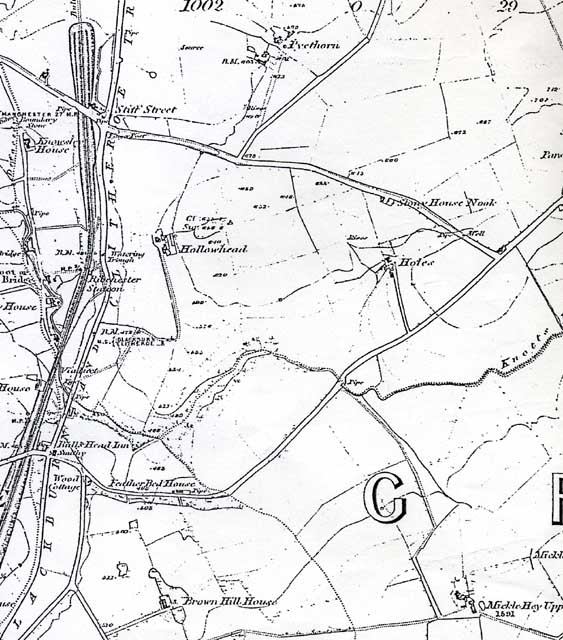

“Id’ wer a little place between Guide and t’ Cross Guns,” he said. Its hafe pulled deawn neaw, bud aw took a fancy to id, an’ bein’ friendly wi’ t’ landlady aw got it. Yo’ know when yo’ goa to a place like thad yo’ go to werk, yo’ve never done. Bud aw’d allus been used to werk fro’ bein’ born. Aw’ll tell yo’ wod aw did last year as aw wer theere. Aw wer 66 years o’ age, an aw mowed every bit o’ t’ meadow misel’ an me an’ t’ wife geet t’ hay. T’ cotton panic hed been on before I went to t’ farm. We hed a bit o’ money saved, bud wi’ seven on us to keep, and nowt coming in, it soon went, o’ bud two peaund. There wer lots o’ people starvin’ then. T’ soup used to come up to Knuzden every day, and them as wor minded could go an’ ged id.”

The town has changed vastly since those early days. Mr. Smalley went on; “I’ my time there used to be handloom weyving i’ Darren-street. Thad’s o’ pulled deawn neaw, and rebuilt. There wor never a building between Brookhouse and wheer t’ tram stops at Wilpshire neaw, except Brownhill and wod they co’ed Carr Cottage and a heause at Bastwell. Aw remember when King William wor creawned. Aw was goin’ to th’ Loine Ends Schoo’ then, an’ on t’ day we hed to goa deawn to chapel-street for buns an’ coffee. Yo’ know that suited t’ lads,” added the speaker with a smile at the recollection. He did not remember the Coronation of George IV. “Yo’ see, they dudn’t used to let children know everything same as they do today. There wor no schools to go to. There wor nod a school nearer to t’ Featherbed except t’ Parish Church. Aw remember, too, as ther’ used to be a barracks i’ King-street wheer t’ sowjers drilled. Aw sometimes used to goa wi’ mi mother to t’ wareheause for pieces an’ aw used to goa across an' watch t’ sowjers at their exercises. Aw soon geet em’ o’ off as nicely as they hed.”

In spite of all the hardships which the story of his early life reveals, Mr. Smalley does not look upon those early days wholly with disfavour. “They talk abeawt hard times today, bud they know nowt abeawt times being bad i’ them days when there wor nowt coming in,” he says, but then adds: “They hed hard times i’ my days, bud i’ mony ways there wer moore pleasure i’ life than there is neaw.” He believes there is too much hurry and bustle about life today, too much disputing, and spitefulness, and anxiety. To put it in his own words, “They seem to mek a lot moore o’ things than they owt to do today, and like as they can’t agree one wi’ another as they used to do. They disagree and they fo eawt and carry on. According to one lot, one Government will be no good; t’ others say id’ll do everything as is wanted , way as they talk. Wod aw say is, if Government does good to one side id must do good to o’. Aw dorn’d believe i’ so much spite, so much anxiety. Led everybody please their selves.”

Mr. Smalley is fond of his joke, and tells with manifest relish how he occasionally “scores” off his friends. “At this time o’ t’ year,” he says, “they’re agate o’ talking abeawt holidays. Some will be gooin’ to Blackpoo’, some to th’ Isle o’ Man, some to one place and some to another. They were talking one day, an’ aw says ‘Aw could like an eawtin to th’ Isle o’ Man.’ They sed as it ‘ud be too much for me and o’ that , soa aw sed ‘Aw con goa to th’ Isle o’ Man an' Paris i’ t’ same day.’ They dudn’t know wod to mek on it . They dudn’t know as there’s a place up above t’ Bull’s Head, gooin’ On Mellor way as they co’ th’ Isle o’ Man, and a row down near Ramsgreave as they co’ Paris.”

There wouldn’t be many holidays in your young days?” said the visitor in conclusion.

There were nooan,” replied Mr. Smalley, “nobbut t’ Bonny Inn races. There used to be races there, t’ first Monday i’ August, bud they fell off a good many years since.”

Ian Maxwell, a Cottontown reader whose family were from Blackburn, sent us some information about his Grandmother, Nellie Maxwell, nee Highton.

The Hightons were a well known building firm in Blackburn and Ian's Grandfather, Laurence Maxwell was a well known local architect.

Nellie was The Blackburn and District Band of Hope Union's 1st May Queen in 1900.*

This article from the Blackburn Times of 12th May 1950 looks back to Nellie's role as May Queen, 50 years earlier.

Ian has sent us this delightful photograph showing the wedding of Nellie Highton and Laurence Homer Maxwell in March 1913. The bridal party are shown outside the Highton family home- Cherry Tree House, in Cherry Tree.

In the photo are my Grandfather(Lawrence Homer Maxwell), Grandmother(Amelia Ellen Highton "Nellie"), Great Grandparents(Richard & Amelia Highton) and my Grandmother's brother and sister(Jack & Mary Highton). Also in the photo are Ellen Maxwell(great grandmother), Jane Carus(groom's sister): others unknown.

Cherry Tree House was situated close to the railway in Cherry Tree. As well as being the family home of the Hightons, it was later the home of local doctor John Byrom Leigh and his family. Sadly it was demolished in 1976 and flats have been built on the site.

*Band of Hope groups existed across the UK. The first was set up in Leeds in 1847. In 1855 a national organisation was formed. The aim was to teach children the benefits of teetotalism, at a time when alcohol consumption was considered a necessity of life. Meetings were held in churches and included religious instruction. Activities were held to keep children away from the temptations and dangers of strong drink.

Blackburn of course had a strong Temperance movement with Mrs Lewis ("the drunkard's friend" ) and her Lees Hall Temperance Mission being particularly prominent.

By Alfred Constantine—Aged 90.

Introduction.

This article written by an O. B. gives an interesting insight into the conditions in Blackburn some 80 years ago, and in itself, is a tribute to the memory of Mr. Constantine, who at the age of 90 can remember events in such detail.

My father was born at Hebden Bridge and we trace his family tree to the reign of Charles II, his ancestor being described as a yeoman. My mother was a native of Rochdale. I was born in Tackettes-street, Blackburn on May 7th, 1856, and clearly remember seeing a man in a white smock, with a tray on his head, crying, “Who’ll buy my crumpets?” I also recall being taken to see a large bonfire and fireworks at the top of the Parks to commemorate the marriage of Edward VII, to Alexandra of Denmark. My family later removed to Rose Cottage Feniscowles, on the old Preston-road, where our nearest Railway Station was Pleasington. The Stationmaster was a short, stout man named Standing. Beyond the station the only building was a R. C. Church. Between Feniscowles and Cherry Tree, stood a large house from which I often saw two boys riding on ponies. One of them in later years became Sir Herbert Whiteley, Mayor of Blackburn, 1892, and M. P. for Ashton-u-Lyne; the other, George Whiteley, became Lord Marchamley, and M. P. for Stockport 1893-1900.

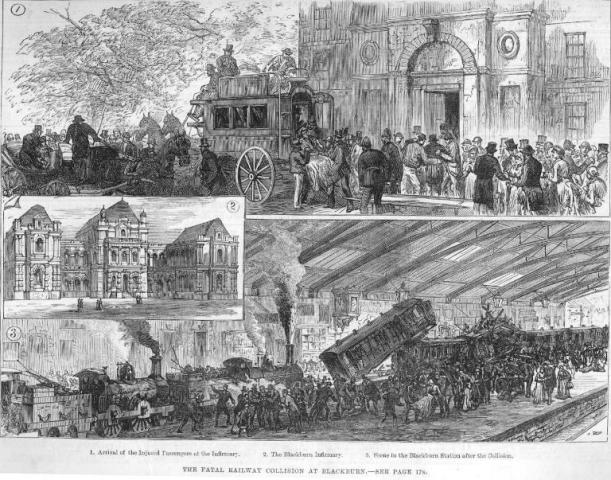

In 1861 came the cotton famine when 30,000 operatives were dependent on charity and soup kitchens. Later, we removed to Alma-street, Blackburn—a far different Alma-street to that which we know today. There was vacant land opposite our house but later St. George’s church was erected here with Pastor Rev. Doctor Grosart. From the top of Alma-street to Simmons-street was Aspden's Timber Yard. At this time my elder brother Richard and myself, became weekly boarders at the Old Grammar School in Freckleton-street. Thomas Ainsworth, M. A. assisted by his brother, George, and teachers Stewart and Briggs were the staff. Richard had a longing for the sea and I remember seeing him climbing over the playground wall on his way to adventure. He was quickly missed and brought home, footsore and weary from Hoghton. Later he was apprenticed to Clayton and Goodfellows Foundry. As a boy I remember many incidents that occurred in Blackburn. Four people skating on Rishton reservoir were drowned,(1) Seven people were fatally injured in a railway collision at Blackburn Station in 1881,(2) An explosion of gas which accumulated in the cellar of the Crown Hotel in the market place, killed five people and injured ten.(3)There was a terrible rail smash at Abergele, and amongst the 33 people killed were the two sons of Mr. C. Parkinson, of Church-street, and their brother-in-law, W. T. Lund.(4) A small greyhound which was found lying in a dry stone ditch was adopted by Mr. W. Briggs, M. P. and won for him the Waterloo Cup in 1872. Her stuffed body can be seen in Blackburn Museum. She was called “Bed of Stone.” Preston Guild was always a great occasion in those days and my parents took me along with them. I was parted from them in the crowd and a kindly policeman took this weeping little boy to the police station, where, along with a dozen youngsters, all “Lost Property,” my distracted parents eventually found me.

In 1878, the cotton operatives went on strike and amongst other destruction burnt down the house of Colonel Jackson at Clayton-le-Dale. My father became a town councillor in 1869 and a Borough Magistrate in 1872. The foundation stone of Paradise-street Church was laid by my eldest sister in 1871, and upon her decease we returned to the Trustees the silver trowel and silver mounted mallet used by her on that occasion. At that time our family attended Barton-street Church, and its chief supporters were Councillor Beads and Messrs. Fowler and Edmundson. To reach the church we had to cross Blakey Moor, which was an awful district, covered in pools of dirty water, old tin cans, rotting cabbage stalks with an occasional dead cat, but no lack of public houses! We children were taken to an exhibition at India Mills, Darwen, and there went up the large ornamented chimney. On the way to Darwen there were blazing iron blast furnaces. When the premises now occupied by Marks and Spencer’s were rebuilt Mr. Richard Ashton, the Librarian, begged the stone bust of Sir Robert Peel, which is now in the Museum. The buildings were named after Peel.

Two Old Boys of the Grammar School, one my cousin, Arthur Constantine, and the other one, John Lewis, founded the Blackburn Rovers, and besides winning the cup six times, in the [18]80’s nearly won the championship of the world!

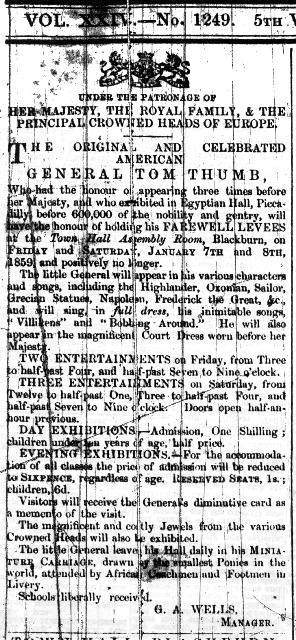

I remember seeing General Tom Thumb and his wife giving receptions at the Town Hall—very profitable for them!(5)

At the top of Preston New-road was a public house, “The Fox and Grapes,” and beyond it a few houses called “Limefield.” The end one was occupied by our friend Carter Brindle, Waste Merchant. After this residence there was nothing but fields, whilst on the left was Woodfold Park.

I was sent to a boarding school at Southport, near to where Hesketh Park was then being made; and I later found this school vanished and a beautiful wooded park has appeared where before was nothing but sand hills. From Southport, I went to Mintholme College, near Hoghton Station. On passing the Cambridge Junior Examination, I was made editor of the Mintholme Times—an extremely clever outside cover was sketched by one of the masters and the reading matter was written by the boys. Each week it was pinned up in the classroom. Its contents were varied. Rabbits or sailing boats for sale (we had a small lake at our disposal), articles to exchange, etc. Each week items of the 1870-1871 war were included. I am fortunate in having kept a copy, which I prize highly. I was now leaving school and the holidays being very near, several of us went to Riley Green and hired a boat to sail on the canal which runs to Whittle Springs. Being tired of rowing, a passing barge gave us a tow. Only I remained in the boat. Another barge from the opposite direction approached to pass and its horse, as usual, stopped to allow its rope to sink. After passing, the horse started again and its rope tightening caught the front of my boat, upsetting it and throwing me into the water. I caught a rope thrown to me and was hauled on board. In the cabin, a stove was burning and the old boat woman (bless her!) stripped me and dried my clothes as well as she could. We then landed and ran to school. I sneaked to my bedroom, changed all my apparel, and put the wet ones in the bottom of my box. On reaching home my mother unpacked it and found at the bottom my damp and mouldy clothes. A confession followed but no reprimand—she was happy that I had escaped.

SOME PERSONALITIES OF MY TIME.

James Boyle. Alderman and Guardian of the Poor. He was a toffee manufacturer whose speciality was “Boyle’s Famous Jap Nuggets.” (There were no chocolates in those days.)

James Cunningham. Tall and portly butler to William Feilden, Esq. He retired from his butling duties and with money saved bought Snig Brook Brewery, which he developed by buying public houses. Very hospitable and fond of sport, he was in turn, Alderman and Mayor, retiring to Lytham, where he died.

James Pilkington, M.P. Founder of Blackburn Infirmary.

Henry Stowe. Amateur actor, butcher and judge at cattle shows

John Skaife. Surgeon, Bookworm and ornithologist; great traveller and collector, his rare medals and coins realised £1,796 at his death. He was a favourite with the working classes and was known as the “Family Doctor.”

William Alexander Abram. The first Librarian, he knew the whole of Lancashire, having walked its length and breadth and spent seven years writing the “History of Blackburn.” He was succeeded at his death by David Geddes, and later by Richard Ashton.

Herbert Railton. A great artistic genius. His drawings of Lancashire medieval buildings are of much historical value.

Daniel Thwaites. Blackburn’s greatest and wealthiest brewer. His heiress married R. A. Yerburgh, M.P. for Chester.

John Smith. A short thick-set man with a broken nose and coarse features. A quarry owner, who had the first chance of buying on easy terms 84 acres of the best freehold land for private houses in Blackburn, but being uneducated he neglected the opportunity of becoming a wealthy man. He became Mayor in 1867 and no matter how distinguished the company he never modified his broad Lancashire accent. One instance; when seated with Sir Justice Willes, hearing an election petition, the later complained of the heat of the room. Jack Smith rose and in a loud voice shouted, “Heigh policeman, hoppen them windas and led sum hair in, do summat for thi brass.” Sir Justice Willes gently smiled. John Smith died insolvent, and his faculties had failed him.

Charles Tiplady. A printer who got his education at the old National School, Thunder Alley and was a capable public-spirited townsman.

Richard Edmundson. A nephew of John Edmundson, inventor of a snuff of peculiar pungency and famous as “Edmundson’s Snuff.” He travelled around with an entertainment founded on what was called “laughing gas". He afterwards exported Lancashire goods to Sierra Leone and made much money. On his decease he bequeathed a sum of money to every congregation in Blackburn.

Richard Dugdale. Engraver and door plate maker. His shop was at the corner of Strawberry Bank. When an old man he engraved the Lord’s Prayer on a piece of silver the size of a three penny bit and also four lines of poetry inside the lining of a mourning ring.

Dr. Grime. Magistrate. A great benefactor to the poor and a crusader against dirt and offenders of sanitary laws. His special physic for many derangements was a week in Blackpool. A poor woman once asked for his bill and in is assumed gruff Lancashire accent he said, “Whoa towd thee to cum here? When I want thee to pay a’ll send for thee. Tek thi brass to Blackpool an’ ged sum fresh air wi’ it.” He was one of Blackburn’s greatest benefactors.

James Wolstenholme. Was an engraver and sign writer near Sudell Cross. He had a son [William] who was born blind and when older the boy went to the College for the Blind at Worcester. He afterwards developed a great genius as an organist He wrote many standard works for the organ which are often included in the programmes of our present day leading organists

A. N. Hornby. (Son of the cotton manufacturer) was a celebrated Lancashire cricketer and will long be remembered by the cricketing world.

SOME OLD BLACKBURN TRADESMEN.

On the left of Sudell Cross (opposite an ornamental street lamp presented by Jack Smith when Mayor) was Garland's Chemist Shop, and half way down towards the Market Square was Gelson's the Hairdressers, while at the lower corner Bateson and Johnson, Milliners. On the right hand side was the Grapes Hotel and below it the Exchange. The building, erected for the cotton industry employers, was also used as a concert room. Below the Exchange was a chemist called Paffard. A pleasant little man wearing Gladstone style collars, he had a great sale of “Dr. Gregory’s Powder” and was generally known as “Owd Paffard.” Facing the Market Hall in Peel Buildings was Sefton, Grocer, and Blackburn and King, Milliners. On the right of the Market Square came Victoria Buildings with Cumberbach and Sons, jewellers; Franklin Thomas, Furniture Dealer and the offices of Thwaites the Brewers. At the top of Darwen-street were Booth and Openshaw, Druggists; Geo. Munroe and Co., Wine Merchants and Miss Derbyshire’s confectioner's shop. The latter was a well setup woman who made the most famous meat pies. She never married and bequeathed all her money to build some beautiful alms-houses. As today, Thunder Alley toffee has a great reputation. Slippers and shoes were bought at Stirrup’s in New Market-street; hats and caps at Umpleby’s in King William-street; coats and suits at Hirst’s in New Market-street. Frankland was the photographer, and I still have a photo he took of me when I was nine years old. My head was placed in a concave iron affair so that I should not move. I recall that I wore a deepish white collar and a large bow tie my mother made out of one of her bonnet strings.

OTHER INTERESTING TIMES.

Garibaldi, who released Italy from the Papal States visited England and it became the fashion in Blackburn to wear a red blouse called a Garibaldi. Crinolines, by the use of steel strips, made women’s dresses very voluminous. Queen Alexandria having a mishap to her foot had a slight limp. So it became the fashion for every woman to limp. With the bustle becoming all the rage, woman set up at the bottom of their backs a bulgy stuffing which they called “The Grecian Bend.” Ladies over 50 when at home wore fancy caps trimmed with ribbon or jet ornaments.

With regard to food, every home baked its own bread and our family always bought a small sack of flour from Richard Shakleton. One of Lancashire’s favourite dishes was “lob Scouse,” fresh meat and potatoes placed in a closed earthenware dish and allowed to simmer many hours. Tripe, trotters, cowheel, and Bury puddings were also very popular, while Irish whisky was a favourite evening drink along with a smoke in a “church warden” pipe.

To give you some idea of prices then ruling: mutton, beef and bacon were 7d per lb, eggs 25 for 1s, butter 1s to 1s 3d per lb. Coal was 16s to £1 per ton, and it usually came from Wigan or Burnley. Wages of farm labourers were 10s a week, and the rent of cottages 1s a week.

Nomination of Parliamentary candidates, previous to the Ballot Act of 1872, was made from a temporary platform from where they addressed their constituents. It was erected on the site of the present Reform Club at the bottom of the Market Place. This was always a rowdy meeting between Conservatives whose colours were orange and blue and the Liberals, pink and green. At one election the military had to be called from Preston.

May I close by sending all good wishes to all Old Blackburnians everywhere. I have a strong affection for my native town and my old school. May they both experience prosperity and happiness,

Notes

1) Rishton Resevoir was a very popular place for skating in the winter months, thousands travelled from all over the county to enjoy the skating there. However on Sunday afternoon January 30 1870 at about 4pm part of the ice broke and four people lost their lives, they were James Smith, Catherine Bleasdale, Hannah Towers and Sarah Ann Towneley.

2) The train crash at Blackburn Station happened on Monday 8th August 1881. The Manchester express ran at full speed into a stationary train just arrived from Liverpool. Seven people were killed with many injured.

3 )Abergele Train Disaster 1868

4) Crown Hotel explosion 1891

5) Tom Thumb appeared at the Town Hall, Blackburn on Friday and Saturday January 7th and 8th 1859 Advert in the B/S Jan. 5 1859 front page.

back to top