Central Police Station Northgate Blackburn

Many of the crimes committed in Blackburn in 1929 seem to have been minor offences linked to the new motor cars, buses and lorries on the streets. The fines for these offences ranged from five shillings for having an inefficient silencer on a motorcycle or paying costs for driving on the footpath to a fine of ten pounds for the mill manager who was found drunk in charge of a motorcar. This fine is significantly higher than the fine a man received for being drunk in charge of an older means of transport- the horse. Fines for the same offence could vary widely: Fines for driving a motor vehicle without a licence could be anything from five shillings to five pounds. Nobody received a prison sentence for a driving offence- not even the man convicted of driving in a manner dangerous to the public after his van collided with a motorcycle, killing the rider. The van driver received a fine of 40 shillings. One man was fined £1 for not having proper control of his motorcycle, and his passenger was fined the usual ten shillings for aiding and abetting a criminal.

Unfortunately there appear to be a fairly large number of dishonest traders in the Blackburn area, selling bread, coal, and sugar in smaller quantities than required. These people incurred fines of between ten and twenty shillings for their crimes. A fine of one pound was given to one particularly dishonest coal seller for carrying unjust weights to enable him to sell short measures without people paying anything less for them. There seems to be an issue with the selling of milk- fines were handed out to people selling milk not of the required substance, nature or quality, selling milk not sealed on premises registered for the purpose, and selling milk without the sellers’ name and address clearly marked. One tradesman was banned from selling milk, in addition to a fine of forty shillings after it was found that he had failed to thoroughly clean the milk receptacles before delivering them.

Christopher Hodson, Chief Constable 1914-1931

Blackburn also had a number of people who ignored the strict laws on ownership of dogs, for example the people who were fined for keeping dogs without licences, without a name and address on the collar, or keeping dangerous dogs- fines- 5 shillings. Certain people were also ignorant of the rules preventing dogs from entering Corporation Park- fine: 5 shillings. Other crimes connected to animals were allowing sheep to stray into a road (fine- 5 shillings), and cruelty to a horse (fine- 20 shillings).

There appears to have been relatively little violent crime in Blackburn in 1929. Just one man was sentenced for unlawful wounding (of his brother) and went to prison for only one month. There was just one case of indecent assault (6 months in prison), and one case of disorderly conduct (fine: 5 shillings). However, there were many cases of assault, for which a fine of ten to forty shillings was payable, or two months in prison for the man who attacked a debt collector with a poker. Some of the men convicted of these crimes were also drunk; particularly those who were charged with assault or disorderly conduct. The usual fine for drunkenness was twenty shillings, although one man was fined forty shillings for being drunk outside the permitted hours for drinking alcohol.

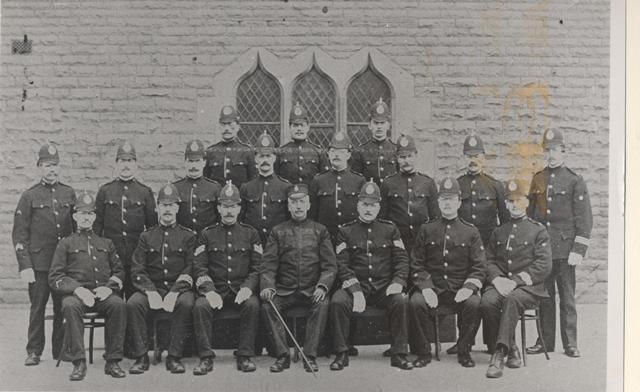

Blackburn Borough Detective Department c1921

Many cases of theft and criminal damage were recorded. Fines of between one and fourteen shillings were handed out for causing damage to doors, windows, and crockery. One man was fined £10 for setting fire to 30 acres of moorland near Sabden. Another was only ordered to pay damages to two householders after altering a water supply pipe and cutting off their supply. There was also the very common fine of five shillings for permitting a chimney to be on fire. Theft often resulted in a prison sentence: three months for stealing £3; one month for stealing a pair of trousers, a padlock, and six shillings; one week for stealing a pair of boots. Two men stole three cars and four tins of paint between them, however received different sentences- one got a fine of £3, the other two months in prison. Few fines were imposed for theft; those who didn’t receive a prison sentence were likely to be released on condition of their good behaviour. A very harsh sentence in comparison was the three years penal servitude imposed on one man for breaking and entering and stealing six stockings, which was his twentieth conviction.

Not all of the poor and desperate people of Blackburn who turned to crime decided to steal to get a little bit more- several people were accused of making false representations to claim unemployment benefit or relief from the rates: Fines of between twenty shillings and £5 were imposed and one woman went to prison for a month. However, another woman was let off for claiming unemployment benefit whilst making a coat, which she then sold for twenty-five shillings.

Blackburn Borough Police, Duckworth Street Section c1912

Other people resorted to begging on the streets- this was not welcome, and one woman who was caught begging was ordered to leave the town. Some of the poor people of Blackburn sent their children out to earn money instead of going to school- a woman who, the court heard, had not left her house for several years, was fined twenty shillings for failing to comply with a school attendance order, made after her daughter had attended school on 7 of a possible 241 occasions. One man was sent to prison for a month for seriously neglecting his seven children in a manner likely to cause them unnecessary suffering or injury, his wife was also charged but got a divorce in the time that passed between their first court appearance and the sentencing, so was considered not to be involved in their continuing suffering.

Two slightly odd crimes committed were conveying the carcass of a dog through a street- forty shillings plus costs, and discharging a toy pistol in the street- also ordered to pay costs.

Overall, the vast majority of crimes were judged to only necessitate a fine rather than a prison sentence, and some criminals received sentences we would view as lenient today, such as the one month in prison for unlawful wounding with a knife, and other sentences seem very harsh, such as five or ten shillings fine for allowing a chimney to be on fire, or twenty shillings’ fine for failing to display the unladen weight on a trailer.

This article was researched by Jonathan, a pupil at St. Christopher’s C E High School, Accrington, whilst on work experience at Blackburn Museum.

By Bob Dobson

Former police officer and now publisher and bookseller Bob Dobson has contributed the following piece, which gives an insight into the care taken to procure the best quality uniforms for Blackburn's Police:

This story from the Blackburn Mail of July 18th 1827 could have been taken straight from a Dickens novel. The young lad seems not to have been neglected or misused. The family do not seem to be destitute; he was just an habitual criminal.

Among the felons transported for life, at the Preston sessions there is a boy only seven years of age*. This unusual circumstance will be best explained by a succinct history of the child’s short, but extraordinary career. His name is Taylor**, and he is the son of a small farmer in the neighbourhood of this town. The boy had scarcely attained his fourth year when he evinced a propensity to steal, by converting to his own use the money he was in the habit of receiving from his father’s customers for milk, which he (the boy) was employed to bring to town every morning. On this being discovered, the urchin was sent to school, but on more than one occasion he pocketed the school money sent by [his father] to the master, and finally he was dismissed from the school in consequence of purloining a case of mathematical instruments. He was next despatched to Manchester, where it was intended he should be bound apprentice, but there he employed himself in picking pockets, and the father was obliged to make up the loss to the plundered individuals. Soon after this, the young rogue sold his clothes, and returned to Blackburn, where he remained several days before his father knew he had left Manchester. The next feat was an attempt at shop robbery, he having been found concealed under the counter of Mr. Boardman’s shop, in Church-street [William Boardman, linen draper] just as the premises were about to be closed for the night. The crime for which he received sentence in the sessions was perpetrated…in the town, where, in open day he dexterously picked a man’s pocket [the man was Samuel Strong] of a tobacco-pouch, ink-horn, and nine pence in money. He was taken into custody, but the magistrate before whom he was sent, hesitated to commit so youthful an offender, and suggested parental correction as the best remedy. The father, however, positively said he could do no more with him, and preferred that the law should take its course, as the only alternative. He was accordingly committed, but his tricks were not at an end for all that. Mr Kay [Blackburn’s constable] compassionating the boy’s youth would not confine him in the lock-up but recommended him to the care of an assistant, who took him home to his own residence for the night. The young thief was stripped and put to bed. In the morning, the assistant who had slept in another room, missed two shillings from his pockets, and sure enough, on searching, the stolen money was found in the lining of the boy's cap. In order he might not grow worse, by herding with old offenders, the little rogue was quartered in the hospital of the House of Correction at Preston, and slept in an apartment with three invalid prisoners. In the course of the night, whilst two of them lay awake but apparently asleep, they observed the boy get up, and steal over to the clothes of the third, and pick the pockets of the only penny they contained, and that penny was found in the thief’s stocking on the succeeding day. And the subject of this lamentable statement has just passed his seventh year!

*The England and Wales Criminal Register of 1791-1892 gives his age as 8.

**The boy was called William Loxam and used Taylor as an alias. It seems strange that such a young boy should have an alias!

I can find nothing about his short life in Blackburn nor any information about his transportation other than the sentence, which is shown in the “England and Wales Criminal Registers of 1791-1892.” Whether he made it to Australia and if he did what happened to him there remains a mystery; unless someone out there knows something!

FOOT NOTE

Nicola Jackson, formally of Darwen, Lancashire and now living in Sydney Australia, sent this to Cotton Town.

“I did a quick search of historical documents and found the following:

UK, Prison Hulk Registers and Letter Books, 1802-1849

William Lomax – Died at Hospital 8th July 1831 whilst on the prison

hulk Euryalus which was moored at Chatham (ship for juveniles until

they reached 15yrs then could be transported)

Sorry to be the bearer of bad news.”

Thank you Nicola, William would have been about 12 when he died. It gives a sad ending to a sad story.

On the night of Friday the 12th of December 1958 at about 11.04pm a man ran into the police station on Northgate shouting that someone with a gun was holding a family hostage.

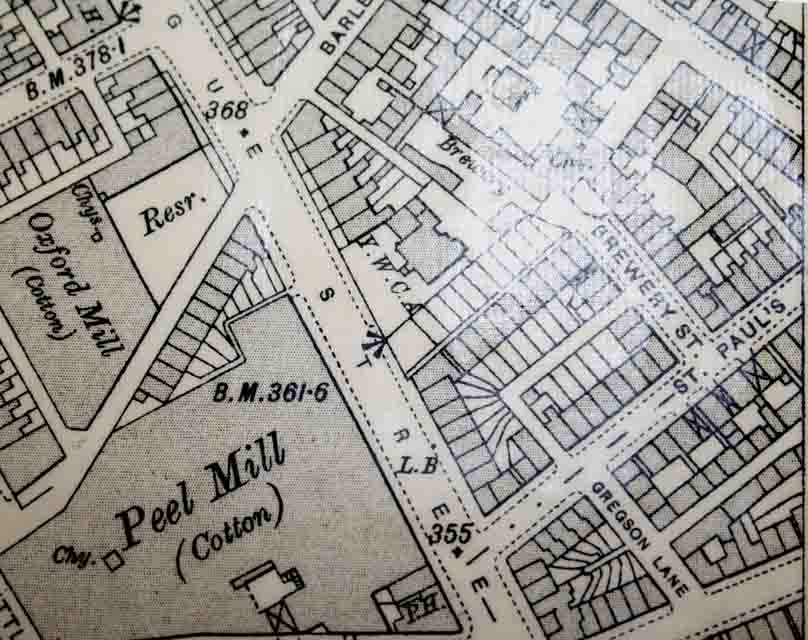

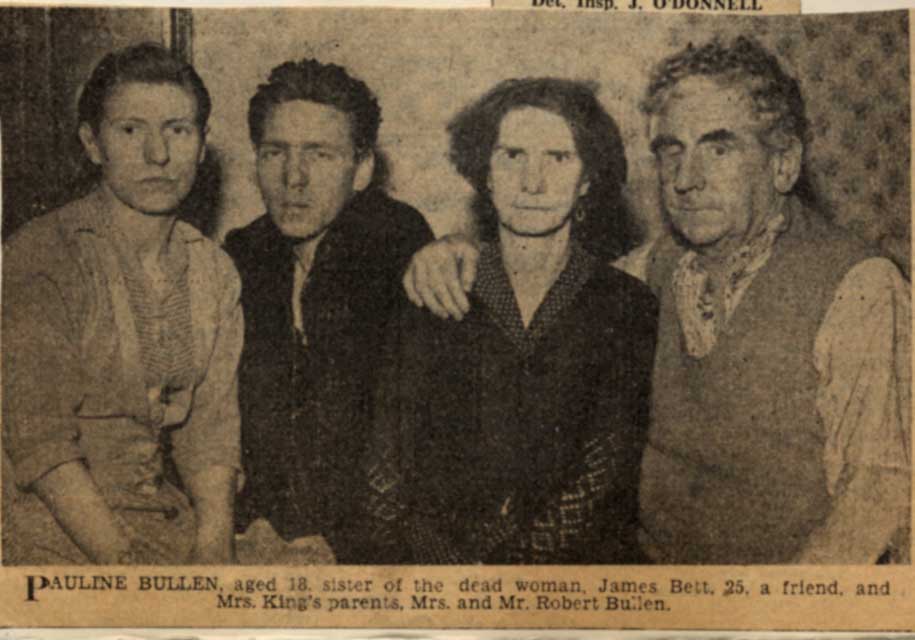

The incident was happening at 8 Brewery Street, a cul-de-sac just of St Paul’s Street Blackburn. The house belonged to Mr and Mrs Bullen. The Bullens had retired to bed at 9.45pm, leaving downstairs, their daughters Sheila King and Pauline Bullen, Sheila’s six-month-old son David, Pauline’s boy friend James Betts and next door neighbour Blanche Cowell.

The siege had started at about 10.45pm with a knock at the front door of the house. Sheila King had got up to answer it. When she opened it she saw her estranged husband, 27 year old Henry King. He pushed his way into the house brandishing a shotgun. The two sisters saw the gun, and panicked, running upstairs to their parents’ room. Mr and Mrs Bullen got out of bed and went downstairs with Pauline, leaving Sheila alone in the bedroom. King told Pauline to shout for his wife to come downstairs. Mrs Bullen, in a temper, tried to get King to leave the house. She was shouting and threw a poker at him, which missed. She then began to bang on the stairs with an empty bottle to try an attract attention from outside, but King had had enough and threatened to shoot her if she kept the noise up. They were now all made to stand in front of the fire in the front room.

King asked Sheila “Do you love me? Will you kiss me? Because you have got to die tonight”. She replied, “You have killed what love I had for you”. Mrs Bullen then suggested the gun was not loaded, which annoyed King and, aiming the gun up at the ceiling fired bringing down a large part of it. King now told them all go upstairs. In the bed room he made his wife stand under a crucifix which was fixed to the wall. They were kept there for about half an hour. Then he took them back downstairs to the kitchen, and they were ordered to stand at one side of the room with King standing between the kitchen table and the back door. He said to his wife “You and me will go back to church and make some new vows”.

Mr Bullen had put the baby into its pram and started to wheel it out but was stopped by King who said “Bring that pram back inside Mr Bullen, quick”. Now things took on a different slant with King threatening to kill himself. He tied the trigger of the gun to a chair with the belt of his coat. He was now getting more and more disturbed. It was now that Blanch Cowell saw her opportunity and manged to get out of the house to raise the alarm.

A taxi driver, Harry Barker, who had been dropping off a fare in the street, heard Mrs Cowell shout, “Go away he’s got a gun”. Getting back into his taxi he drove to the police station, reported the incident then returned with three plain clothed police officers, DC’s John Covill, Jack Riley and Peter Halliwell. When the police arrived Pauline Bullen said “Here's the Police,” to which King replied, “Now then we’ll have some fun”. The front door was already open and DC Cavill ran straight into the front room. King pointed the gun at Cavill from the kitchen and shouted “Get back, it’s loaded” Cavill held out his hand and told King to give him the gun. He refused and fired it, wounding Cavill in the groin. Without any hesitation King turned round and shot his wife in the back as she stood by the kitchen fireplace. PC Riley pulled Cavell out of the house. King shouted to the rest of those still in the house, “Get out before someone else gets it! Get out the lot of you”.

After they were all gone PC. Halliwell slammed the kitchen door on King. One of the constables sent Harry Barker, the taxi driver, back to the police station for assistance. Detective inspector’s James O’Donnell, Jack Harrison and Herbert Taylor arrived on the scene with police backup. Inspector O’Donnell entered the house. The door to the kitchen was shut and he shouted through it, asking King if he could go in. O’Donnell finally persuaded him to open the door. Inspector O’Donnell and DC Halliwell went into the kitchen, King, recognising Halliwell and not wanting him there shouted at him to get out. After some negotiating, he agreed to let Inspector Harrison come in with O’Donnell. Inspector Harrison stood at the side of the kitchen door, while Inspector O’Donnell faced King. The kitchen was in darkness, the only light coming from the front room. King said that he wanted to make a statement and Inspector Harrison began to ask King about what he had done. Inspector O’Donnell stood with his note book open, but was not writing anything down. This seemed to upset King and he asked why O’Donnell was not taking down the statement, then, raising the shotgun he fired, hitting Inspector O’Donnell in the chest, just beneath his heart. The Inspector fell. King then turned the gun on Harrison, threatening to shoot him Harrison picked up a chair threw it at King and managed to jump back through the kitchen door to safety. Inspector O’Donnell somehow dragged himself along the kitchen floor to the door and was pulled out.

At 1pm the police sent for Henry King's brother, who arrived shortly after, King spoke briefly to him and threw a note out of the window written by his wife Sheila to another man. It read;

Dear Dennis.

Just a few lines to say I am OK. Hoping you can say the same. I got home all right. I have not seen him yet as I have to get my case settled. It was very nice to get to know you.

My writing is not very good as I have a bad hand. Would you send me a photo of you. I will send one to you later. My Mum bought me a skirt, coat and underwear. Dennis, could you send me a bit of money as I want to pay solicitor? If you can’t I understand love.

Well Dennis this will be all for now. So till I write again I will say

Cheerio. Love

Sheila.

The Chief Constable R.R. Bibby and the Deputy Chief Constable J.M. Rodgers arrived at the house and were quickly made aware of the situation. Mr. Bibby called for the police officers to be armed, and issued with tear gas. Police dogs with their handlers were also brought in.

At about 2.15am after a three hour stand-off, it was decided that the siege should be brought to an end. Orders were now given for the police to enter the house by force. Tear gas was thrown through the kitchen window, and a police dog was sent in closely followed by armed police officers. There was a shot heard from the kitchen. King shouted that he had shot himself. When the police got to the room he was laying on the floor, the dog was barking at him. King was wounded on the left side of his chest. He held the gun, a twelve bore repeater shotgun, in his left hand. On the floor the police found five spent cartridges a further sixteen live cartridges were found in his pockets when he was searched.

Chief Inspector O’Donnell, DC. James Covill and Henry King were all taken to Blackburn Royal Infirmary. Covill was badly wounded, with a gunshot wound to his groin, which had fractured his pelvis. The wound was not life-threatening. King had a slight chest wound. He was later transferred to Walton jail hospital. After being admitted to the Infirmary, Inspector James O’Donnell underwent a major operation. He was then in a critical condition. Later in the day he improved slightly, but then his condition began to deteriorate and it was felt another operation was necessary. At about 10 pm he was taken to the operating theatre, two hours later, just before midnight, on Saturday the 13th of December, Inspector James O’Donnell died.

Forty seven year old Inspector James O’Donnell had, before joining the police, been in the Irish guards, leaving the army in 1932. When war broke out in 1939 he rejoined his old regiment. 1940 saw him in Holland, and whilst fighting a rear guard action with the Irish Guards, covering the evacuation to England of Holland’s royal family, he was wounded. He was sent to a hospital in The Hague and while there was captured by German forces, having to spend the rest of the conflict as a prisoner of war. In 1945 O’Donnell made his escape. He evaded capture for eleven days, before he met up with British Forces near to Belsen Concentration camp. When he got back to England, he was awarded the Military Medal and four months later he received the bar to go with it. In December 1945 O’Donnell rejoined the police and two years later was promoted to Sergeant. In 1955 he was promoted to Inspector and made head of the CID in Blackburn. He had been married to Florence O’Donnell for about 11 years. They lived in Higher Croft Road, Lower Darwen, and had no children.

Henry King and Sheila Bullen had been married In January 1957, while King was in the air force. Their marriage was not a success there had been numerous separations. About the end of November 1958 Sheila once again left her husband and with her six month old son moved back to her parents' house in Brewery Street.

Henry King had gone to a Pet shop on Penny Street at about 3.30pm on the day of the siege and had bought a Browning automatic five shot shotgun with twenty-five rounds. At 8pm King went into the Dun Horse Hotel on Mincing Lane and started to talk to Sheila Whipp, a lady he knew. In the course of their conversation, he gave her a live cartridge She, having no idea what it was' gave it him back. He then told her he was going to shoot his wife and baby that night. At about 10pm, after having about 6 or 7 whiskeys and dry ginger he left the pub saying to Sheila Whipp on his way out “Ta-ta. You won't see me again. You will read about it in the papers tomorrow”. He made his way to Brewery Street stopping of to pick up his gun.

THE TRIAL

On the 16th of January 1959 Henry King was committed to stand trial at Manchester Assizes by Blackburn Magistrates, charged with the murders of his wife Sheila King and Inspector James O’Donnell. The trial at Manchester Assizes began on the 10th of March 1959. When asked for his plea on the murder of his wife, King at first pleaded guilty. He was then asked to plead again. This time he pleaded not guilty. He also pleaded not guilty to the charge of the murder of Inspector O’Donnell.

Witnesses were now called, for the prosecution and the defence. Both King and DC Cavill were brought to court in ambulances. Cavill had to be helped to the witness box by colleagues. The defence wanted the charges of murder reduced to one of manslaughter due to diminished responsibility and they set out to show this throughout the trial The jury, which consisted of ten men and two women, were told that King had said he both loved and hated his wife. He had told a psychiatrist that she had been a prostitute and then later denied ever saying it. She would laugh at him behind his back. Throughout this King sat in the dock holding a Bible on his knee.

The jury was also told that when he was a teenager, King had spent time in borstal for theft. He had later joined the RAF as an assistant cook working his way up to corporal, however he had had a hard time of it, especially after he got married. While in the camps he had kept his wife on a tight leash and quickly broke up any friendships she made. Later, after being posted to Germany, he would often upset the military powers and also the locals who worked in the camp. He was described as a bully and quick to lose his temper with those under him and this included his wife. He was paranoid that the police, both civil and military, were persecuting him, and the defence suggested that King had suffered from paranoid schizophrenia. Much more evidence was given as to the state of King's mind at the time of the incident at Brewery Lane, with the defence trying to show that it stemmed from mental problems he had in the past.

At the end of the three-day trial, the jury were sent out to consider its verdict. After deliberating for four hours, they had failed to reach a finding. The judge sent them back. After a further half hour ,they retuned with a verdict. He was found not guilty on both counts of murder, but guilty of manslaughter.

On the 13th of March 1959 Henry King was sentenced to life imprisonment for the manslaughter of his wife Sheila King and Inspector James O’Donnell.

All the above information was taken from the local newspapers

Written by Stephen Smith, a CottonTown volunteer

The murder and mutilation of Emily Holland, 1876

"I never had such a thing in my head when I sent her for the ’bacca"

On the Tuesday 28th March 1876 seven-year-old Emily Holland had dressed in her Sunday Best to go to school at St Alban’s RC School. There was a Government inspector coming to test the pupils and as a bright intelligent girl she wanted to both look and do her best. At half-past-four, at the end of the school day she set off home; around her waist she had tied a ribbon in celebration for winning a prize. Although her home, at 140 Moss Street, was only 400m away on Moss Street she never made it and despite increasingly frantic searches by her father, James Holland, she was never seen alive by her family again.

James searched throughout Tuesday night and on Wednesday morning the police became involved.

Emily was described as having a pale complexion and dark hair; she was of a slender build. She was wearing a black frock, a black hat, a purple and white scarf and boots.

The people in the area suspected a local man must have been responsible because Emily was an intelligent child who would not have gone off with a stranger.

The police’s first suspect was a roughly dressed man who Emily’s friends had seen in the street when she disappeared. He was described as 40 years of age, about 5' 6" and having the appearance of a navvy. He was wearing a dark coat, vest and trousers and with dark hair.

His description was circulated across the north of England and this led to a huge manhunt and men were arrested as faraway as Leeds. However, the man in the street, who was eventually arrested, proved to be a ‘red herring’.

All of this activity did not bring the searchers any closer to finding Emily until a gruesome find on Thursday morning indicated her likely fate.

It was Thursday, shortly before 12 o’clock when Mrs White went to investigate a parcel lying in a field at the end of Bastwell Terrace, off Whalley Road.

The site of the discovery is now covered by houses but then it was by the side of a cinder path leading to Lower Oozebooth Farm.

The parcel was made from newspaper and it had attracted a local dog. Inside she found the torso of a child. Shocked, she called to a man, Mr Dewhurst, a labourer, who was passing and he fetched the police. When he arrived at the scene PC Rostron marked where the body was found and took the parcel to the Police Station.

It’s worth remembering that at this time there was no Forensic Science Service and although police detectives did exist, none were available to Blackburn’s police force.

The police called upon three doctors to help them. The Blackburn Police Surgeon was Dr Martland; he worked at Blackburn Infirmary and he was helped by Dr Cheesbrough (who also worked at the infirmary) and Dr Patchett. The work of these three men was to be instrumental in catching the murderer. When the family were told of the discovery Mrs Holland collapsed and James Holland went to identify the remains. The naked torso was that of a young girl but as it missing the head, arms and legs, James was unsure. The identity of the body was confirmed by Emily’s aunt; because at the child’s bath time she had noticed a white birthmark on her back, this birthmark was on the torso. The aunt also told the police that she had given Emily a piece of fig pie and the autopsy, performed by the three doctors, confirmed the presence of figs in the child’s stomach. The autopsy concluded she must have died before 6 o’clock and discovered that the child had been subjected to a violent sexual assault.

The townspeople were horrified by the discovery and the search began for the missing body parts. On Saturday the legs of the missing girl were discovered by Richard Fairclough in a culvert at Lower Cunliffe. Like the torso they were wrapped in a copy of the Preston Herald but this time the murderer had made more of an effort to hide them.

The next day, Sunday, thousands of people from the town set out to search for the rest of her body but the head and arms remained undiscovered. They had even emptied all the cesspits and ash pits.

The arrests continued. The children in the street, who included Emily’s cousin, told the police that when Emily disappeared she had been sent on an errand to buy three ha’pence of tobacco by a man who had offered her £1 if she did so. Perhaps as a sign of their desperation, they even arrested George Cox, the owner of the Tobacconist’s shop on Birley street, even though he was nowhere near the scene when Emily had disappeared. The police eventually tracked down and arrested the man seen in the street, he was called Robert Taylor and his circumstances must have been very frightening even though there was very little evidence against him; as one contemporary observed “Yet people have been hanged for less, and Robert Taylor probably escaped a similar doom by the narrowest chances.”

Reward money totalling £300 was offered; £200 was offered for finding the rest of the body and the Home Office offered £100.

Police make a breakthroughThe breakthrough in the case came from the forensically minded Dr Martland,he noticed that Emily’s body was dirty and also that hairs were sticking to the body. On closer examination the hairs were seen to be of varying length and colour. In addition, some of the hairs were very short and turned out to be men’s whiskers.

He told the police that the body must have been dismembered on the floor of a barber's shop.

This new evidence led to the Police searching all of the barbers shops in Blackburn. Nothing was found but the police’s suspicions were now focused on two local men – Denis Whitehead whose shop was on Birley Street, close to its junction with Moss Street and William Fish whose premises were at 3 Moss Street; Emily would have walked past Fish’s shop on her way to and from school.

The police weren’t the only people to suspect Fish. For whatever reason, local people also suspected him and when a rumour spread that the child’s head was in Fish’s shop a crowd of a thousand people gathered in the street outside.

The police hastened to reassure the crowd that they had searched the shop and that nothing had been found. However, the pressure was on Fish and he agreed to be interviewed by the Blackburn Standard newspaper and he took the opportunity to explain his alibi.

In the meantime the family had quietly buried Emily’s remains.Perhaps surprisingly, the funeral did not attract a large crowd. Her remains were buried in a polished oak coffin finished with silver handles. The hearse carrying her coffin was followed by three mourning carriages for family and friends. As it made its way down Moss Street, it passsed William Fish's shop where he sat on the doorstep smoking his pipe.

The funeral started at 11 o’clock and the funeral was taken by Reverend Berry and Reverend Dunderdale.

Blackburn’s Chief Constable Mr Potts came to the funeral and the undertaker was Mr Walker.

The police investigation seemed to have stalled. Fish’s shop was searched a second time but nothing was found; following this Whitehead was arrested but because he rented the rooms in his house out to four men they were able to provide him with an alibi.

The breakthrough came on 16th April when a man called Richard Taylor travelled from Preston and offered the police the use of his Bloodhound, called Morgan, together with a Springer Spaniel he also owned.

That same day, Easter Sunday, the police arrived at Whitehead and Fish’s shops simultaneously. They secured Fish’s shop and took the dogs to search Whitehead’s shop first.

The dogs found nothing in Whitehead’s shop and so the police took the dogs round to Fish’s shop.

The shop was in a two-up two-down brick built terraced house, like all the other housing in the area. The front room, downstairs, was the shop with its barber’s chair and mirror. There was a fireplace in this room, as there was in every room. In the other room on the ground floor there was a slop-stone (a shallow sink) under the window and, under the stairs, a pile of coal for the fires. Upstairs there were two rooms which were probably quite bare because Fish lived with his wife and family at the other end of Moss Street, at number 162, quite close to the Holland’s home.

The dogs were taken into the shop through the front door and went straight through into the back room and started to sniff around the slop-stone. The police officers searched it but could find no traces of blood. Richard Taylor took the dogs upstairs, accompanied by the Chief Constable, William Fish and his wife. In the back room nothing was found but in the front room the dogs ran straightway to the fireplace and started barking.

Richard Taylor moved forward and startled the Chief Constable, Joseph Potts, by thrusting his arm up the chimney. Fish’s wife started to shout at Taylor but it was too late, Taylor stood up from the fireplace with a parcel in his hand. In this, wrapped in a copy of the Manchester Courier, they found the charred skull of the girl and “some other bones”.

Fish must have known that the game was up and he said not a word as the parcel was opened

Outside a large crowd had started to gather, several thousand angry people. The police realised that if they got hold of Fish he would be killed and so Chief Constable Potts stood in the front doorway and talked to the crowd whilst his other police officers got everyone else in the house away down a back street.

When Potts told the crowd of their discoveries a huge cheer went up.

The crowd followed Potts down into town where Fish was already locked up in a cell, in the Police Station at the back of the Town Hall.

The next afternoon Fish told PC Parkinson where the rest of the clothing was and that he wanted to make an confession “so that the innocent would not suffer.”

Fish’s confession

I told Constable William Parkinson that I burnt part of the clothes, and put the other part under the coal in my shop; and now I wish to say I am guilty of murder. I further wish to say that I do not want the innocent to suffer . At a few minutes after five o’clock in the evening, I was standing at my shop door, in Moss Street when the deceased child came past. She was going up Moss Street, I asked her to bring me one half–ounce of tobacco from Cox’s shop. She went and brought it to me. I asked her to go into my shop. She did. I asked her to go upstairs, and she did. I went up with her. I tried to abuse her, and she was nearly dead. I then cut her throat with a razor. This was in the front room, near the fire. I then carried the body downstairs into the shop; cut off head, arms and legs; wrapped up the body in newspapers, on the floor; wrapped up the legs also in newspapers, and put those parcels into a box in the back kitchen. The arms and head I put in the fire. On the Wednesday afternoon I took the parcel containing the legs to Lower Cunliffe; and, at 9 o’clock that night, I took the parcel containing the body to a field at Bastwell, and threw it over the wall. On Friday afternoon I burnt part of the clothing.

On the Wednesday morning, I took part of the head which was unburnt, and put it up the chimney, in the front bedroom.

I further wish to say that I did it all myself; no other person had anything to do with it.

The foregoing statement has been read over to me, and is correct. It is my voluntary statement, and , before I made it, I was told that it would be taken down in writing , and given in evidence against me.

(Signed) WILLIAM FISH

Witnesses, Robert Eastwood, Superintendent

William Read, Superintendent

Joseph Potts, Chief Constable”

Fish’s trial

Fish was taken to Kirkdale Goal near Liverpool and sent for trial at Liverpool Assizes in late July.

Given his confession, the fact that he had told the police where to find the rest of Emily’s clothes and that he had even corrected the Police Surgeon at the inquest, Fish’s trial might have been expected to have been very brief indeed.

Nevertheless, The Judge, Justice Lindley, instructed that a plea of ‘insanity’ was entered on Fish’s behalf and appointed a lawyer, Mr Blair, to defend him.

After all of the evidence had been heard and summed up by the judge, the jury were asked to consider their verdict. They did not even bother to leave the Jury Box but conferred briefly amongst themselves and within a minute the Foreman of the Jury returned a verdict “GUILTY.”

Fish’s last words, before the Judge passed the death sentence on him were “I never had such a thing in my head when I sent her for the ’bacca.”

William Fish was hanged at Kirkdale Goal on 14th August 1876. Uniquely for a nineteenth century murder case, there was no attempt to raise a public petition asking the Home Secretary to show mercy.

Although completely forgotten today, the murder of Emily Holland was, in its time a notorious case and raises some interesting issues which still resonate today.

It was the first time that a Bloodhound had been used to help detect evidence of a crime. In the most infamous crime of the nineteenth century, the Jack the Ripper murders, bloodhounds were used because a policeman remembered their successful use in the Emily Holland case.

The lack of police detectives in Blackburn at the time of the murder is noteworthy as a very early example of the use of forensic science by the doctors assisting the police.

The response of the newspapers was quite different from today. Even though it was a paedophile crime there was no moral panic such as we would see today but Fish’s physical appearance was discussed at length. He was only 5' 2" but because of the popularity of phrenology his peculiarly-shaped head was described in detail and Liverpool Waxworks had a model of his head made even before his trial had taken place.

After his execution some of William Fish’s family history came to light. Of course, it in no way excused his actions but does perhaps offer a clue to them.

William’s mother died when he was three years old and his father then ran away leaving his children to be put into the Workhouse. One day, whilst playing on the workhouse roof, William fell forty feet and landed on his head. Amazingly, he wasn’t killed but he had to have three pieces of bone removed from his skull, leaving him with a misshapen head. He would certainly have suffered a brain injury and, even if he hadn’t, one of his brothers was described as “an idiot” and his other siblings as “feeble minded”. Ironically, the Prison Governor described William as “the gentlest prisoner he had ever met”.

Robert Taylor, the man in the street seen by Emily’s friends, was lucky to escape with his life as society’s desire to see someone held responsible for the crime would probably have led to his trial for her murder if Fish had not been caught.

Today, very little survives to remind us of this terrible crime; the murder of a lively, bright and intelligent little girl on her way home after winning a prize at school.

The houses on Moss Street were all demolished in the late 1960s but Emily’s grave survives and can be found in Blackburn Cemetery. The map below indicates the location.

Researched by Justin Smith, student from Beardwood School, whilst on work experience at Blackburn Museum.

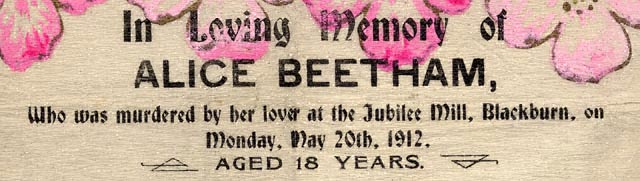

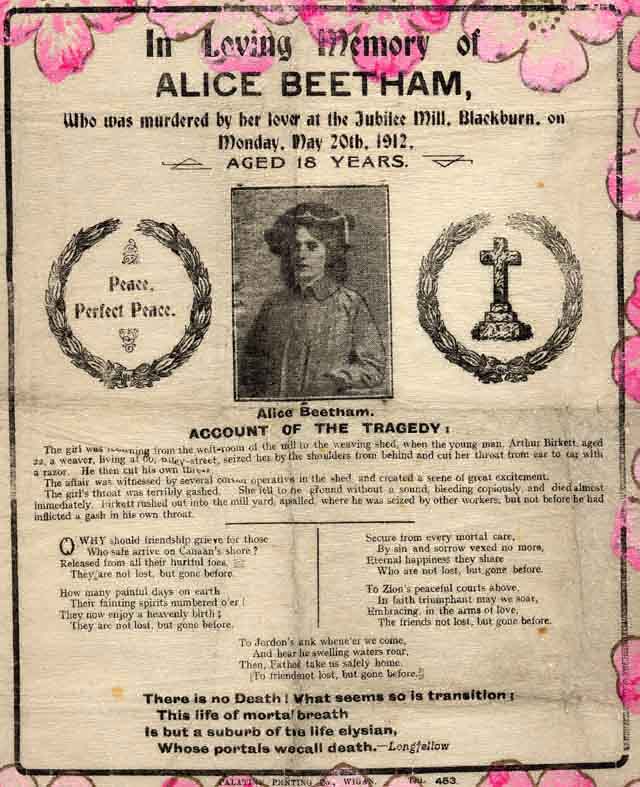

Alice Beetham was 18 years old, and lived in Billinge Street with her parents, her three brothers and a younger sister. She attended St Joseph's. worked as a weaver at Jubilee Mill in Gate Street. She had been 'keeping company' with Arthur Birkett for about three weeks. Her father was a driller at a foundry. That's all we know. Her photograph is more revealing. She is pretty and aware of it. She is not discomposed by the photographer, but neither does she trouble to pose for him. She looks away, aware perhaps that her full gaze might reveal too much. Had she got into that habit, knowing her eyes would give her away. How often had she avoided Arthur Birkett's glare when he demanded to know why, why didn't she want to see him anymore?

Alice Beetham had always been beyond poor Arthur's reach. She'd caught the eye of many a better man than him. What a pity it is that her kind heart led her to look at Arthur Birkett at all.

Ironically, on the very page of the Blackburn Times that records the tragedy of her death are detailed the weddings of the week. These are 'society' weddings. Note the difference in the photos, how confident and serene these young people look. There would have been no list of gifts in the paper if Alice had lived to be married, no cheques, no cases of silver apostle spoons from guests who'd motored in from Lytham. Maybe she'd have been happy though with the right man and her kids and neighbours to chat to when she stood on her doorstep at night

Arthur Birkett was 22. He was a weaver at Jubilee Mill, living in Riley Street. His father was dead and he lived with mother, grandmother and little sister. His brother had recently emigrated to Canada.

The newspaper photograph, presumably taken when Birkett was a young boy, shows an anxious face with a suggestion of truculence about it and with something petulant about the bottom lip.

We know a little more about Birkett from his behaviour during his trial. It's hard not to get the impression that he felt ennobled by his 'love,' hard too not to get the impression that people took him at his own estimation. Over 50,000 signed the petition for a reprieve, including Alice Beetham's mother, though not her father. Hard to detect any real remorse, let alone any real love for Alice. He gave her a chance; she stubbornly refused, so she had to pay.

There must be something darker there though. It takes real savagery to decapitate someone with a razor. There must have been something monstrous in his psyche. It is said he was glad not to get a reprieve and went to his death with fortitude. He must have known there was that within him that he could not live with.

Was his death a release for him? He wrote from Strangeways that he hoped to be united with Alice in heaven, where presumably she would have seen the error of her ways and repented. No doubt she rushed into his arms with joy, when he entered through the pearly gates, anxious to be forgiven for her silliness.

Jubilee Mill

There had been a mill on the site between Gate Street and Copy Nook since the early 1850s. In 1886 this was demolished to make way for a modern mill with the latest machinery. It opened in 1887, the year of Victoria's golden jubilee and was named Jubilee Mill accordingly. It was operated by D. and W. Taylor and had 570 looms.

In 1894 John Taylor took control and was still in charge 18 years later when Alice Beetham was murdered there. No doubt John Taylor was on the premises at the time. It was said of him that he arrived in the morning with the earliest workers and was still there at eleven o clock at night.

John Taylor died in 1915. Harwood Prospect Mill took over and closed in 1932, when the premises were renamed Orient Works and drying machinery was manufactured there.

"There's only one girl for me..."

The murder of Alice Beetham took place on Monday 20th May 1912; it was gruesome murder which took place at Jubilee Mill Gate-street where they were both employed. For several weeks, she had been going out with Arthur Birkett of Riley Street. On the previous Thursday she had told Arthur that she no longer wished to go out with him. It is believed that Alice's father did not approve of Arthur, which may have been the reason for breaking off the relationship, or it may have been because she felt Arthur was too passionate.

Not long before the murder he had spoken to a fellow weaver about Alice saying "There's only one girl for me, and if I don't get her I'll have none". On the day after Alice had finished with Arthur he went to the home of another weaver, Mrs. Wagg who was a friend of both of them. He told her that Alice had "chucked him". She tried to console him, saying "there are plenty more". Arthur made a remark "I will chop her.... head off". At the time this seemed like an innocent remark spoken in the heat of the moment, but was later to assume greater significance.

"You look crammed, what's to do?"

On that fatal Monday morning Arthur and Alice turned up for work as usual, by 6 o'clock they were at their looms in the weaving shed. Another weaver, Mrs. Wilkinson said to Arthur "You look crammed (upset), what's to do?" Arthur explained about the situation with Alice. A couple of hours later, during the breakfast interval, Arthur went to a nearby shop where he enquired about buying a razor. He looked at a few and finally purchased one for 1s 6d (about 13 pence). When questioned later, the shopkeeper thought he seemed like an ordinary person, perhaps rather quiet.

She Died Almost Instantly

Arthur returned to the mill. Alice took her weft can and made her way to the weft warehouse. She passed Arthur who followed her in to the warehouse. Alice picked up her weft and went to the door. Arthur followed and grabbed her from behind, putting his arm around her throat. She screamed and fell to the floor. Arthur also fell to the floor. He had cut her throat. The wound extended from ear to ear. It severed everything right down to the spine, including nicking the bone.

She died almost instantly. Arthur then used the razor on himself, causing two wounds to his throat, one superficial, the other about half an inch deep. It all happened so quickly that no-one could have stopped Arthur. Witnesses thought that he was trying to kiss her, but the blood soon made them realise that a horrible crime had taken place.

Eye Witness Accounts

Below are some accounts given by eye witness’s

John Dewhurst, 74 Skiddaw Street;

"The girl had been for some weft. I saw her returning front the weft shop. She came through the weaving shed door with a can full of weft. Birkett immediately followed and I saw him seize hold of her from behind. They had their backs to me, and I could not tell that he had anything in his hand, but he seemed to draw it across her neck. She immediately fell to the floor, and I rushed towards them. I was about three yards away I grasped him and threw him to the floor, and then saw a pool of blood on the ground coming from the girl’s body. I immediately ran for the manager."

The Mill Manager, Mr S. Smith;

"When I rushed to the scene everybody was greatly excited. I immediately went to the girl, who was quite dead, her head having been nearly severed from her trunk. I next went to Birkett who was lying on the floor. I found him bleeding profusely from his throat. He had two cuts on his neck - one either side - but he had missed the front of it. I bandaged his neck and immediately sent for the police from Copy Nook Station. I then went back into the weft shop and by the rails, on the floor, I found a razor.” The manager found it utterly impossible to continue working so upset were the operatives, and eventually the factory was closed. Many of the women weavers fainted outright.

Susie Tattersall of Coddington Street;

"When I went in Beetham and Birkett were standing there close together, Birkett was saying something to the girl, who did not appear to want to bother. She got her weft and was just opening the mill door, when Birkett put his arms around her neck. With them having kept company, we thought he was trying to kiss her, and we laughed. But then I saw blood on her clothing and they both fell to the ground. Edith Rimmer and myself tried to pull him away, but he resisted and we ran for the manager. I never saw a razor at any time."

Edith Rimmer of Artillery Street;

"I was standing in the weft place, when I saw Birkett rush to the girl. The next thing I knew was that both Birkett and Beetham were on the floor. The girl struggled for a second, seeing blood and hearing someone shout "He's cut her throat". Tattersall and myself got hold of Birkett. We pulled at his shoulders, but could not get him back until he seemed to faint and fall back. Dewhurst was hold of him, so we went to inform the manager and to fetch a doctor."

Mrs Wagg, of Laurel Street;

"I saw Beetham push open the door, then I saw her drop in the doorway. She kicked her legs up: two or three times, and I rushed to her. I was excited because I knew something of the relations of the couple. Alice was an intimate friend of mine. I was horrified to find her in a pool of blood, with her head nearly off. I rushed to the interior of the shed and screamed and people rushed to the door. I swooned and was carried out and sent home. I am told many people fainted.”

The Inquest

Alice's body was taken to Copy Nook Police Station and Arthur was taken to the Infirmary. His injuries were not life threatening.

The Coroner, Mr. H. J. Robinson, opened the inquest on Alice Beetham, on Tuesday 21 May 1912. He said “it was an inquiry into the death of a girl, aged 18 years, a weaver, who was killed by having her throat cut at a mill on Monday morning. On the first day only evidence of identification was given, and the inquest was adjourned. Thomas Edward Beetham, the father of the Alice, said his daughter was 18 years old on the 23 August last. She was a cotton weaver, and had worked at Gate-street Mill ever since she began to work. She was in perfect health. He told the hearing that he did not see her before she went to work on Monday morning, as on Mondays she went to the mill before he got up.

The Coroner asked if he knew Birkett. Mr Beetham said he had only seen him once, about fortnight ago at the bottom of the street when I was coming home. He had been courting with Alice for about 5 weeks.

The Coroner said that was as far as he could carry the inquiry that morning. The inquest was then adjourned to 9.30 on Friday the 31st May at the Town Hall. The proceedings had lasted a quarter of an hour.

The Resumed inquest

Mr. H. G. Robinson resumed his inquiry into the death of Alice Beetham on the Friday morning at the Town Hall. No members of the public were allowed into the court. Those in attendance were Mr. I. G. Lewis, Chief Constable, Superintendent C. Hodson, and Inspector Pomfret. Arthur Birkett sat in the dock, looking pale and ill. The police surgeon, Doctor Bannister gave his evidence saying “I found a deep incised wound 2½ inches behind left ear to 2½ inches behind right ear, all the way around the neck apart from about four inches at the back. This could all have been done in one stroke, using a considerable force to inflict the wound.” Birkett suffered two self-inflicted wounds to the neck. The one on the right was about five to six inches long and about half an inch deep, severing one of the muscles. The one on the left was merely superficial.

Mrs. Lily Wagg, of Laurel-street, a weaver at Jubilee Mill, told the inquest that she had been a friend of the deceased's for two years. Birkett and Alice had had tea at her house. The couple had been together for about six weeks. Three weeks before the tragedy they had spent the afternoon and part of the evening at her house, and a week prior to Alice’s death she, her husband, Alice and Arthur had gone to the pictures. At that time they were all very good friends. Three days before the tragedy – Alice had told her "I can't take to Birkett and will have to give over going with him." When the mills closed in the afternoon they left work together. They saw Birkett outside, and all three went down the street. That night Birkett called on Mrs. Lily who had friends in the house, so she went out to him. He said "Alice has chucked me", he asked if Alice had told her it. She answered "No". Her husband who had joined them said to Birkett "There are plenty of women beside her" to which the young fellow replied, "But none like Alice to me".

The Coroner asked if Birkett made any threat. Mrs. Lily told him he said he would cut her head off.

She told the inquest that on the Monday of the tragedy, Birkett and the girl met in the mill about 7 a.m., but although he was quite close to her, Alice did not speak to him, but walked past him. At breakfast the girl told her that Birkett had stared at her, and she had not spoken to him. At about 8.45am Mrs Lily saw Alice go to the weft warehouse carrying a weft can. Birkett followed behind her, also carrying a can. They both went through the door. From her looms she could see into the warehouse. She saw Alice pushing the door open with her can in order to return to her looms, and then noticed that she was pulled back. The girl next dropped on the floor with her feet in the doorway. She did not see who pulled Alice back. She went towards the girl; found that she was streaming with blood, and on bending over her saw that her throat had been cut. Birkett was lying on the floor near her. Mrs Lily fainted from the shock.

The Coroner briefly summed up, after which the jury, without retiring, returned a verdict of "Wilful Murder" against Arthur Birkett, who was committed in the coroner's warrant to take his trial at the next Manchester Assizes. Birkett was in a state of collapse, and had to be carried down the dock steps.

On June 4th Birkett appeared before Blackburn Magistrates and was remanded until the June 5th whilst notes of the evidence could be transcribed. He fainted as he was leaving the dock. On his next appearance he was more composed. The verdict was that he "feloniously, wilfully and of malice aforethought killed and murdered Alice Beetham". He was then committed for trial in Manchester.

The Funeral of Alice Beetham

Alice's funeral took place the following Saturday the 25 May. A collection was taken at the mill, with some of the money going to her family and the rest to provide a beautiful floral tribute. Young girls held bunches of flowers, which were added to the other wreaths and flowers around her coffin in the kitchen of her home. There was a large wreath sent by the workers at the Jubilee Mill. On the accompanying card was written 'With deepest sympathy from the workpeople of Jubilee Mill'. Hundreds of people called at the house to view the body, and crowds lined the route of her funeral cortege. She was buried in the Roman Catholic portion of Blackburn Cemetery.

The coffin was of polished oak, with silver plated fittings and covered with a purple velvet pall, on which was embroidered a golden cross. On the plate of the coffin lid was the simple inscription:

“Alice Beetham Died May 20 1912. Aged 18 years. R.I.P.”

The Trial

Arthur Birkett was tried at the Manchester Assizes on the 5th July 1912, before Mr. Justice Bucknill having recovered from the injuries sustained when he attempted to cut his own throat. Mr. Gordon Hewart and Mr. A. R. Kennedy, prosecuted, While Mr. Lindon Riley defended him. When asked by the judge Birkett, who appeared calm and collected, pleaded "Not guilty"

Mr. Gordon Hewart said “the facts of the case were comparatively few and quite free from complexity. It was difficult to see, if the evidence for the prosecution was accepted, how the jury could escape the conclusion that this was a deliberate and premeditated murder.”

“It was”, he continued, "A painful but a plain case". On the defences, indication, that the prisoner was not responsible for his own actions, he said that “one or two things would have to be proved, first that by reason of infirmity of mind, due to mental disease, he did not know the quality or nature of the act, or that, if he did know, he did not know that the act he was doing was wrong.”

Mr. Riley for the defence called no evidence, but proceeded to address the jury.

He said the jury had two alternatives to the verdict of wilful murder, and on those two alternatives he based his defence. One was that at the moment of the committal of the act that the murderer was insane, and the other was that the circumstances of the case entitled the jury to regard it as a case of manslaughter. Were there not elements which would entitle them to reduce the charge to one of manslaughter? If the crime was something else, then he submitted that it was due in a moment when the prisoner was not in full possession of his reasoning faculties.

After the judge had summed up the jury retired at 2.45 returning after only sixteen minutes with a verdict of "Guilty of wilful murder".

The Judge donned the customary black cap and said “Arthur Birkett you have been found guilty upon the clearest evidence of a very, very cruel murder - the murder of your sweetheart - a murder premeditated and determined and cruel... you have forfeited your life. Make your peace with your maker, I implore you". Birkett passed out and was supported by two warders. Loud sobs came from the gallery as Birkett was led away.

Birkett Writes to His Family

Arthur Birkett's family tried to get him a reprieve, his mother wrote to the Queen asking for clemency for her son, as she was widowed and depended on him as he was the "breadwinner". Just as there was great sympathy for Alice's family, equally there was much sympathy for Arthur's mother and family. Indeed the Beetham and Birkett families had made their peace with each other, as they had both suffered terrible bereavements. The petition failed and no reprieve was given. While Birkett appreciated the endeavour to secure a reprieve, he was not sorry that the petition failed.

A letter was sent by the prisoner from Strangeways prison, Manchester to his Family, It read;

“My dear mother, brother, sister, and grandmother,

I know you must have been, like me, awfully upset. It breaks my heart to think of the suffering I have caused, not only to myself, but you all. But, my dear mother, I am beginning to think there is such a thing as Fate and what has to be will be. I can never explain how much I love you all, and would give up the world to make you all happy; but none of us know what we have to go through, and how we have to end up in this world. I hope and pray, however, God will forgive me all my sins.

I shall be waiting for you all in Heaven and I hope I shall meet Alice God bless her. I am wishing she likes me as much as I more than like her. I have not taken to anyone like her; but to think it should come to this!

I am looking forward to seeing you all, because I know you will be waiting to see me. It breaks my heart to think how we have to meet, and know what is in store. But God says, "The Sea shall give up the dead", and we shall be together for evermore. It is an awful and hard end, but think we shall be together in the next world, and it will not be like this weary world of trouble.

You must let me know if any of my dear relations in Preston want to come, but anyway, I will write to them. I would like you to send me, as soon as you can, George, that photograph of Alice, and I would like you, George, to send me a photograph of yourself; you know I am more than proud of you.

I will now conclude with my best love and wishes to you all.

You’re unfortunate and ever-loving

Arthur.

P.S. Good night. God guard and bless you all.

The Execution

On Tuesday morning the 23rd of July 19112, at Strangeways Prison, Manchester, Arthur Birkett, was led from his cell to the place of his execution. Outside the prison over 700, people had collected, which was one of the biggest crowds that has gathered at an execution in Manchester for many years. It was a quiet and orderly gathering. The one topic discussed was the subject that had drawn the people together. The Newspapers reported that “Birkett rose at an early hour on Tuesday morning. He was thoroughly resigned to his fate. He was dressed in the dark blue serge suit that he wore at the trial. Pale but composed, he chatted with the warders, thanking them for their uniform kindness to him. Then he concentrated his attention on the photograph of his dead sweetheart, and the group portraying his mother, grandmother, brother, and sister, and Mrs. Beetham. It was only on Monday that he received this group, which had been specially taken, and he was overjoyed in getting it. Of breakfast prisoner partook sparingly. Since his incarceration he had welcomed the visits of the chaplain, to whom he had become attached. When the officials entered the cell shortly before eight o'clock Birkett rose to meet them, and though he could not repress all signs of emotion he bore himself with fortitude. He quietly submitted to the pinioning process. Then the final procession was marshalled, the chaplain (the Rev. R. D. Cruikshank) leading the way, reciting the burial service, followed by Birkett, with warders in close attendance, after whom came the Under-Sheriff (Mr. Arthur Ratcliffe-Ellis, of Wigan), representing the High Sheriff of Lancashire; the governor of the prison (Major J. O. Nelson); the prison medical officer (Dr. Edwards); visiting justices; and the chief warder, with Lamb, the assistant executioner, who had previously bound the condemned man's arms. A few short strides led to the gallows, and when the condemned man was placed on the trap Ellis, who officiated as executioner, rapidly completed the necessary adjustments. Immediately afterwards Arthur Birkett passed into eternity. Just after eight o'clock the solemn tolling of the prison bell intimated to the public that the sentence had been carried out. Subsequently the Under-Sheriff (Mr. Arthur Ratcliffe-Ellis) informed a reporter that the execution had been expeditiously and satisfactorily performed. Subsequently the following notice was posted on the prison door: Declaration of Sheriff and others. We, the undersigned, hereby declare that judgement of death was this day executed on Arthur Birkett in H.M. Prison, Manchester, in our presence. Dated this 23rd day of July, 1912. ARTHUR RATCLIFFE-ELLIS (Under-Sheriff of Lancashire) R. A. ARMITAGE (Justice of the Peace for Lancashire) J. O. NELSON (Governor of the said prison) R. D. CRUIKSHANK (Chaplain of the said prison). Another notice from the surgeon, Dr. John Edwards, certified that on making an examination of the body he found that Birkett was dead.”

The Newspapers also reported what was occurring in Blackburn on the morning of the execution;

“The early morning scenes in the vicinity of Mrs. Birkett's house in Riley-street, Blackburn, were of such an impressive character that they are not likely to be soon forgotten by those who witnessed them. Long before seven o'clock relatives and friends had assembled in the house and among those who arrived later were Mrs. Beetham and the Rev. F. G. Chevassut, vicar of St. Thomas' parish. The table in the centre of the room was literally covered with wreaths and floral tributes from all quarters, and the whole company, for the most part attired in sombre black, were overcome with grief. The Vicar opened the proceedings by reading two appropriate hymns, followed by portions of Scripture, and afterwards he went through part of the Church of England burial service. As the fatal hour of eight o'clock, the time fixed for the execution, drew nigh, the family party, now numbering between 30 and 40, went on their knees, and were engaged in silent prayer for several minutes. Outside, several hundred people had collected, including a large number of mill operatives clad in factory garb, and on the stroke of eight, when almost every blind in the street was drawn they joined in singing such well-known hymns as "Jesu, Lover of my soul," "Nearer, my God, to Thee," and other pieces which were favourites with the condemned man. The vicar offered words of solace and comfort to the bereaved mother and her family. George Birkett was so overcome with grief that he had to be assisted into a rear room, where he received the attention of a nurse who was present. As Mr. Chevassut left the house the mourners joined in singing, "God be with you till we meet again," and several hundred voices outside took up the refrain. Afterwards the service was continued by one of the women present until the arrival of a Salvation Army captain, and he stood on a chair outside the house door and offered prayers and words of counsel to the large concourse of people. Men reverently bared their heads, and many were moved to tears, whilst the women and girls were very much affected. Mrs. Birkett announced that Mr. Chevassut had very considerately placed 12 pews in St. Thomas's church at the disposal of the mourners for a special memorial service on Sunday morning, whilst there would be a second service at Furthergate Congregational Chapel (Where Birkett was brought up) in the evening. She extended an invitation to neighbours and friends to attend. In the midst of the services a telegraph messenger arrived with messages of sympathy from well-wishers, and he was closely followed by the postman with one of Birkett's last letters home. Among those present were Mr. Thomas Bibby, Mr. Harry Reynolds, and Mr. Mathias Rogerson, representing St. Thomas' Conservative Club, and the latter told a Pressman that the club members had subscribed a beautiful miniature monument as a gift to Mrs. Birkett to place in her house. It would be enclosed in a glass case, would stand 18 inches high and would bear the inscription: "In loving memory of Arthur Birkett, Born July 27th, 1889; died July 23rd, 1912. On the other side would be the words: "Son, thy sins are forgiven thee."

Souvenir Napkins were issued

Souvenir napkins were issued to commemorate the event showing a photograph of Alice, a short account of the tragedy and a poem about death. This was produced by the Palatine Printing Company of Wigan. They also issued similar napkins to commemorate other tragic events such as a pit disaster in Wigan in 1910 and the sinking of the Titanic in 1912.

Below is information sent to cottontown relating to the murder of Alice Beetham.

Winifred Beetham

Whilst talking to my Grandma, I found out that her Aunt, Winifred Beetham, was scalped while operating a spinning machine in a mill in Blackburn. She survived the accident but her hair never grew again and so she always wore a headscarf.

Her daughter, my Grandma's cousin was murdered in Jubilee Mill, Gate Street, Blackburn on Monday the 20th of May 1912.

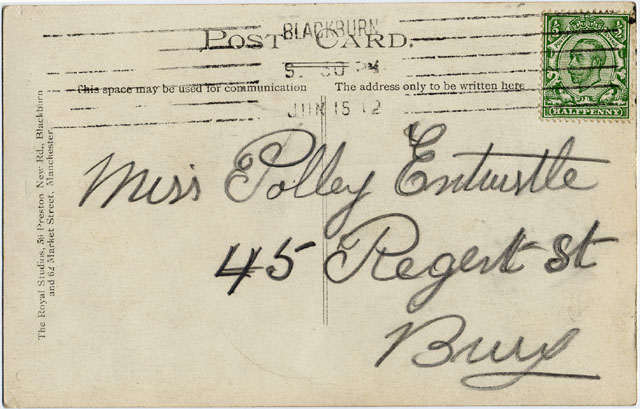

New image of murdered mill girl

Cottontown acquired image of Alice Beetham. A gentleman from London kindly loaned us this postcard of Alice. It was sent through the post to a Polly Entwistle of Regent Street, Bury on 15th June 1912. This was shortly after the date when Alice was murdered on 20th May, 1912. There is no message on the card.

Sources;

Darwen New

25th May, 1st June, 8th June, 6th July, 13th July, 20th July ,27 July 1912.

Acknowledgements

Diana Rushston