Rehousing Slum Tenants

Tintern Creasent, Little Harwood c1950.

In order to meet its obligations under the 1930 Act, the Borough had to undertake the rehousing of 56 households. It planned 25 houses on a site previously purchased in Brothers Street 'containing the minimum floor space required by section 101 of the Blackburn Improvement Act'. (20)

The 1882 Local Act laid down a minimum 690 square feet for a two-storey house. The houses were probably intended to house some of the smaller families displaced. A number of larger units were later added, bringing the total number of houses planned to 52. The cost was estimated at over £21,000. An analysis of directory information for the areas covered by clearance areas show 'labourer' to be given as the head of household occupation in no less than 17 of the 27 clearance area homes for which data is listed (21). Four other households have female heads. It is clear that in these run-down and (presumably) cheap inner areas, the social mix differed widely from that found at Green Lane.

The government rejected the town's initial plans for the Brother Street houses. It insisted that the superficial floor area of the four bedroomed houses be reduced from 950 square feet to 880; the three-bed from 776 to 760 and the two bed from 690 to 650. The cost estimate thus fell to £19, 613 (about £377 per house or under half that paid at Green Lane in 1920). The Ministry also instructed that the four-bedroomed houses should only be used to accommodate households with seven or more members.

Having re-evaluated this scheme, the housing committee received a letter from the Blackburn & District Building Trades Employers Association, stating that it was 'not prepared to recommend members to build houses for letting to the working class (under the Act) (22). In the event a tender from a Manchester builder was accepted. Most of these houses were built in a new street, Beaumaris Avenue - off Brothers Street itself and only a few hundred yards from the earlier Green Lane development.

The Council owned and ran the local Electricity Works and established a new scheme for the Brothers Street estate. A fixed charge of 1/- per week was collected at the same time as the rent (which already included charges for rates and water). This charge included the consumption of 126 units per annum, beyond which any extra units would be charged at the special low rate of 1/2d each. The object was to assist the new tenants to avoid debt: the Borough Treasurer calculated using an established formula the rent that should be chargeable (based on cost) and means-tested rent rebates that would be available to individual tenants. If income or commitments changed, then tenants were required to notify the Town Clerk. In a controversial move, the housing committee proposed that:

'necessary plain furniture at a capital cost to the Corporation not exceeding £18 per house (should) be supplied to those tenants who will be displaced from clearance areas and individual houses... whose furniture is, in the opinion of the Medical Officer of Health, unsuitable for admission to a Corporation house.' (23)

At first the intention was to sell to the tenant furniture needed to replace any condemned by the Medical Officer. Eventually a scheme was adopted that led to the council providing the furnishings which would then have the same status as other fixtures and fittings. A small special committee of councillors would examine each case individually, and the value of the furnishings supplied would not exceed that of the condemned items. Thus, in the worst instance, a family could be told:

• Their home was insanitary and must be demolished. A tiny and distant house would be supplied in substitution.

• If they could not afford the new rent, they may apply for a means-tested rent rebate.

• Their furniture was to be inspected but if too vermin-ridden to be moved to the new house, it would be burned, and a group of strangers would decide what must be replaced. This would then be obtained on the basis of the lowest tender.

Not all of the displaced found their way to Brothers Street. Some sought their own alternative private accommodation when demolition took place (their furniture still being disinfected). If a tenant, having moved into Council accommodation, subsequently decided to move elsewhere, they could apply to take the new furniture with them, but the house had first to be 'approved', and the furniture would remain council property. In another case, when the £18 limit was insufficient, the tenant had to defray the additional cost.

Thirteen cases were reviewed by the special committee in June 1935 - there were several other meetings. The furniture, obtained from Jepson's, included extending tables, sideboards, a tallboy, chests, small chairs, armchairs, beds, spring mattresses and covers and flock bed sets. Blackburn Co-op supplied sheets, blankets and pillowcases. The houses themselves had been built with fitted stoves and wash-boilers. (24)

The housing built in Beaumaris Avenue/ Green Lane, and later at Higher Hill, was inadequate to cope with the numbers displaced by slum clearance. The Committee decided to 'utilise the large-type houses which are at the time vacant on the various corporation housing estates for rehousing persons displaced from houses included in clearance areas and from individual (insanitary) houses.' (25)

In 1939 another decision 'to reserve twenty houses at Brownhill and Green Lane for rehousing tenants from the fourteen clearance areas now awaiting confirmation' led to protests, and a petition from Green Lane residents. (26)

In 1936 the Corporation negotiated a scheme with the Blackburn Property Owners Association, whereby the Borough would become the tenants of suitable vacant houses and then re-let them to the displaced. (27)

For example, 18 St, Albans Place was rented at 12/- per week plus rates and let again at 17/- including rates etc; the council to find the difference. When a tenant moved home to comply with the overcrowding regulations, the Council paid his removal expenses. The majority of Brothers Street estate residents would have consisted of families relocated from clearance areas. Directory data reveals a notable proportion of labourers and of weavers as well as several female heads. A collier and two bricklayers are typical of trades listed. In terms of social composition, rent paid, house size and attitude to their semi-rural location, there would have been significant differences between these two neighbouring communities.

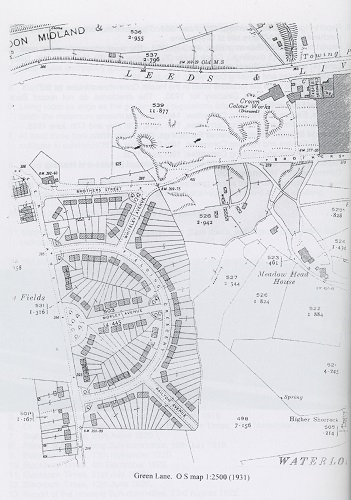

Map of Green Lane Estate 1931

Appendix

Benefits available to Blackburn's first municipal tenants

When performing a ceremony to mark the completion of the Borough's first block of council houses in Green Lane, Housing Committe Chairman Alderman J. Fielding listed a number of benefits associated with the houses. A local newspaper reported these advantages to be as follows:

1. A separate bathroom with a hot water cylinder which also heats a linen cupboard.

2. The W.C. was in the main building and so was approachable under cover.

3. Rear lobbies to protect the outside scullery doors, adding to comfort.

4. Coal-house and pantry accessible from lobbies - not from outside the house.

5. Stairs lit by a window.

6. Living room as large as the government regulations allowed, with windows designed to catch the maximum amount of sunlight.

7. At least three bedrooms and sometimes four, as 'there were hundreds of two-bedroomed cottages in existence'.

8. Three quarters of the houses also had a separate parlour.

9. The sculleries were work-rooms, their use as living rooms being discouraged. They were equipped with gas oven and boiler, sink and drainage board and ample shelving.

10. Space was available in every house for a perambulator.

11. Each living room had built-in dresser with glass doors, with fitted cupboards in the bedrooms.

12. Hot water was available at the scullery sink, bath and washbasin.

13. Bedrooms were, when possible, on the sunny side of the house. At least two had fireplaces, with adequate ventilation in the others.

References

1. Blackburn Times, 13th November 1920. The paper was reporting the formal opening of the Green Lane development.

2. Cited by Beattie, p 157 in the Borough's bid for city status in 1934.

3. 1921 census reports - Lancashire, table 3. The figures divide the total area of the ward into the number of dwellings; and so includes streets, industrial buildings, open spaces etc.

4. Report of the Special Sub-committee on Housing, Minutes. Blackburn Borough Council, 27th November 1918.

5. Report of the special sub-committee, 23rd July 1919.

6. Dr. Addison's letter reproduced in the Blackburn Times, 15th November 1919.

7. Blackburn Times, 24th April 1920.

8. Report of the Housing Sub-committee, 16th July 1919.

9. Blackburn Times, 13th November 1920.

10. Blackburn Times, 4th December 1920.

11. Blackburn Times, 31st July 1920.

12. Blackburn Times, 12th June 1920.

13. Report of the Housing Sub-committee, 23rd August 1922.

14. Minutes, General Purposes and Paid Officers Committee, 24th September 1923.

15. Barrett's Directory of Blackburn, 1925 and 1935.

16. Blackburn Times, 1st June 1922.

17. Minutes, Estate and Housing Committee 21st August 1939. The Committee resolved to take no action until the Medical Officer has ascertained the position by conducting a census of the properties in question.

18. Report, Housing Sub-committee 12th June 1931. The same meeting approved the purchase of the 7½ acre site at Green Lane.

19. Report of the Health Sub-committee, 4th July 1933. The seven clearance areas were Brunswick Street (5 dwellings), Crook Street (3), Meadow Lane (6), Nab Lane (10), Daisy Lane (4) and Denville Street (3).

20. Minutes, Estates and Housing Committee, 19th June 1933.

21. Analysis based upon the locations listed in the Health Committee minutes for 20th November, and Barrett's Directory for 1930. The directories do not record Back Meadow Lane or Spring Lane.

22. Minutes, Estates and Housing Committee, 14th May 1934.

23. Minutes, Estates and Housing Committee, 12th April, 20th May and 17th June 1935.

24. Reports of Special Sub-committee on Furnishings, 20th June 1935.

25. Minutes, Estates and Housing Committee, 18th December 1936.

26. Minutes, Estates and Housing Committee, 19th June 1935.

27. Report of Health Sub-committee, 7th July, and minutes of Estates and Housing Committee, 16th November 1936.

Image of Houses

Green Lane, O S map 1:2500 (1931)

Sources

Primary:

Barrett's Directory of Blackburn: 1919, 1925, 1930, 1935 and 1939

Blackburn Borough Council: Electoral Rolls, 1920 to 1936

Blackburn Borough Council: Minute Books, 1918 to 1939

Blackburn Times: Various

HM Government: Blackburn Improvement Act, 1882

Blackburn Library: Local Studies photograph collection

Office of Census and Population: Census reports, Lancashire, 1911, 1921, 1931

Ordinance Survey: 1:2500 scale plans of Blackburn, 1930/31, 1937 and 1956

Secondary:

Beattie, Derek Blackburn: Development of a Cotton Town. Halifax Ryburn, 1992

Burnett, John - A Social History of Housing, 1815-1970. London. Methuen, 1980

Clarke, J.J - A History of Local Government of the United Kingdom. London. Herbert Jenkins, 1955

Morgan, N - Deadly Dwellings. Preston, Mullion Books 1993

Power, Anne - Hovels to High Rise: State Housing in Europe since 1850. London, Routledge 1993

Swinson, Arthur - The History of Public Health. Exeter, Wheaton Books 1965.

Image of street on housing estate

Blackburn Local History Society Journal 2000-2001. Page 17.

Transcribed by Shazia Kasim

Published March 2025