James Cunningham | William Ewart Gladstone | William Arthur Duckworth | Joseph Harrison

Rev Dr Nightingale | James Hargreaves | Samuel Crompton | Richard Arkwright | John Kay | Roger Haydock

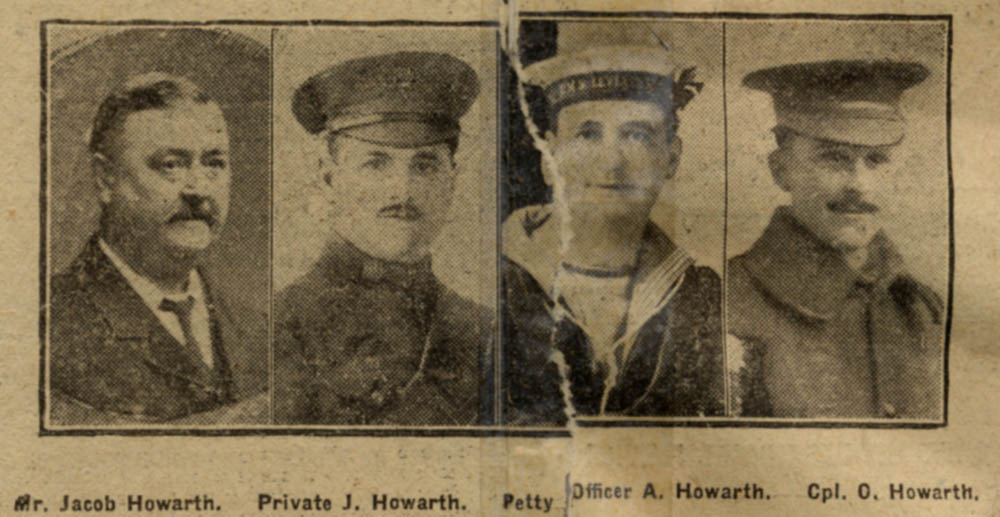

Dr James Taylor Thom Ramsay | David Johnson | Kathleen Ferrier | John Spencer | Jacob Howarth

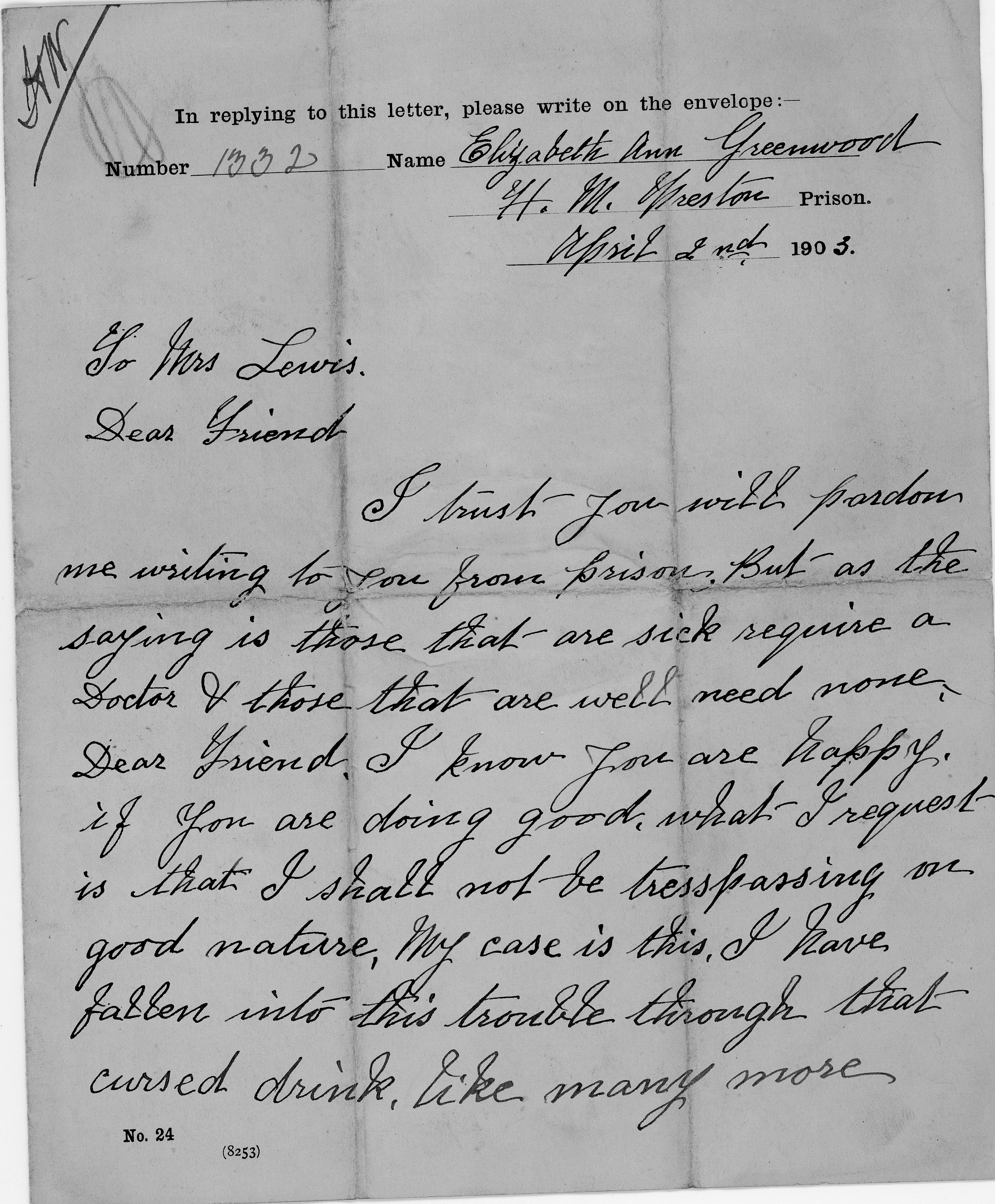

| William Kenworthy | Mrs Elizabeth Ann Lewis | Rev. Dr. Robert West Pearson | Robinson Bradley Dodgson

Mrs. Elma Amy Yerburgh | Darwen’s First Woman Magistrate | Lucy Mellodey | William Griffiths, M.B.E. | James Dixon

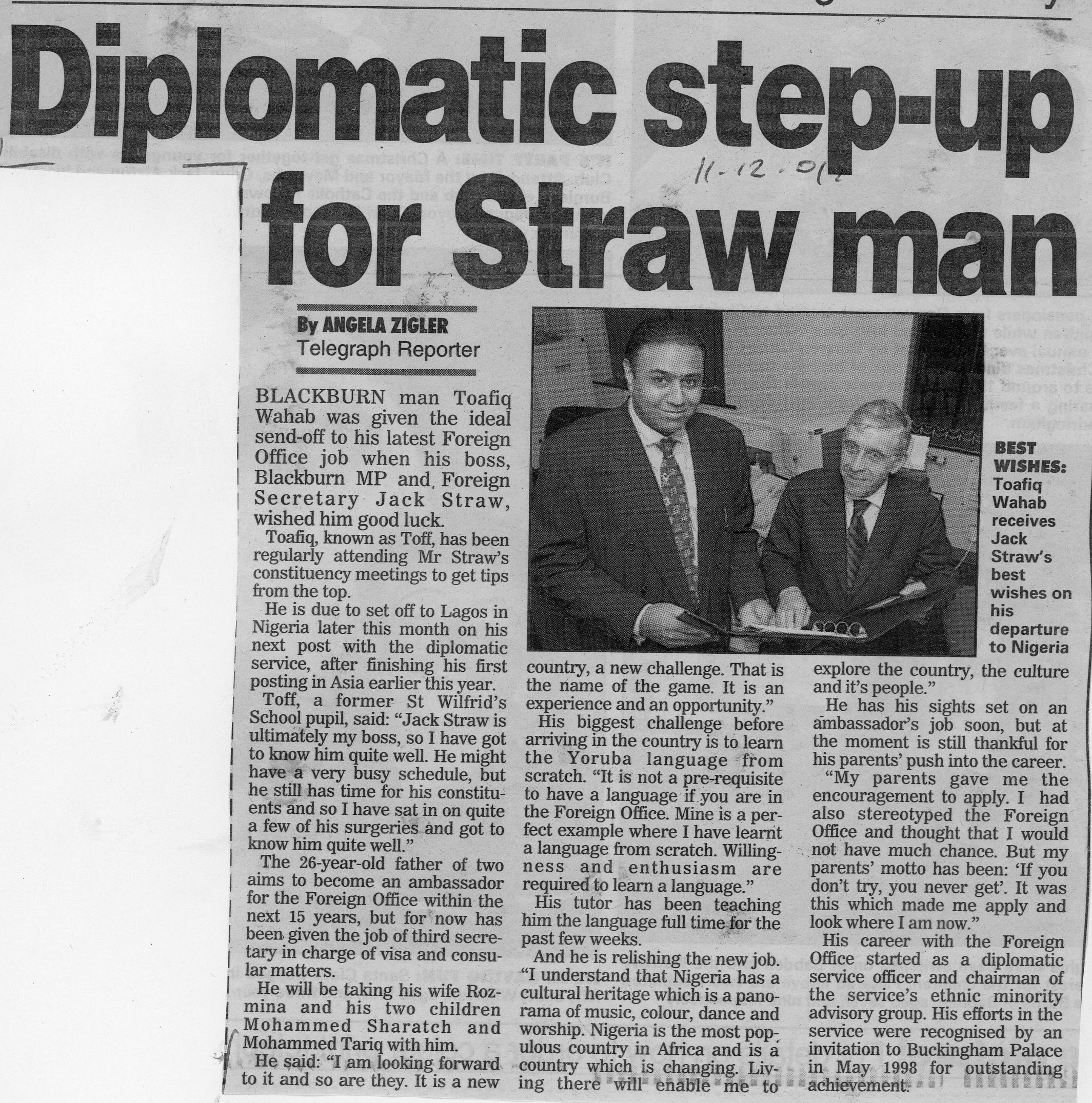

Toafiq Wahab | Charles Haworth | Thomas Whewell | Frederick Thomas Marwood | Briggs Holden Marsden

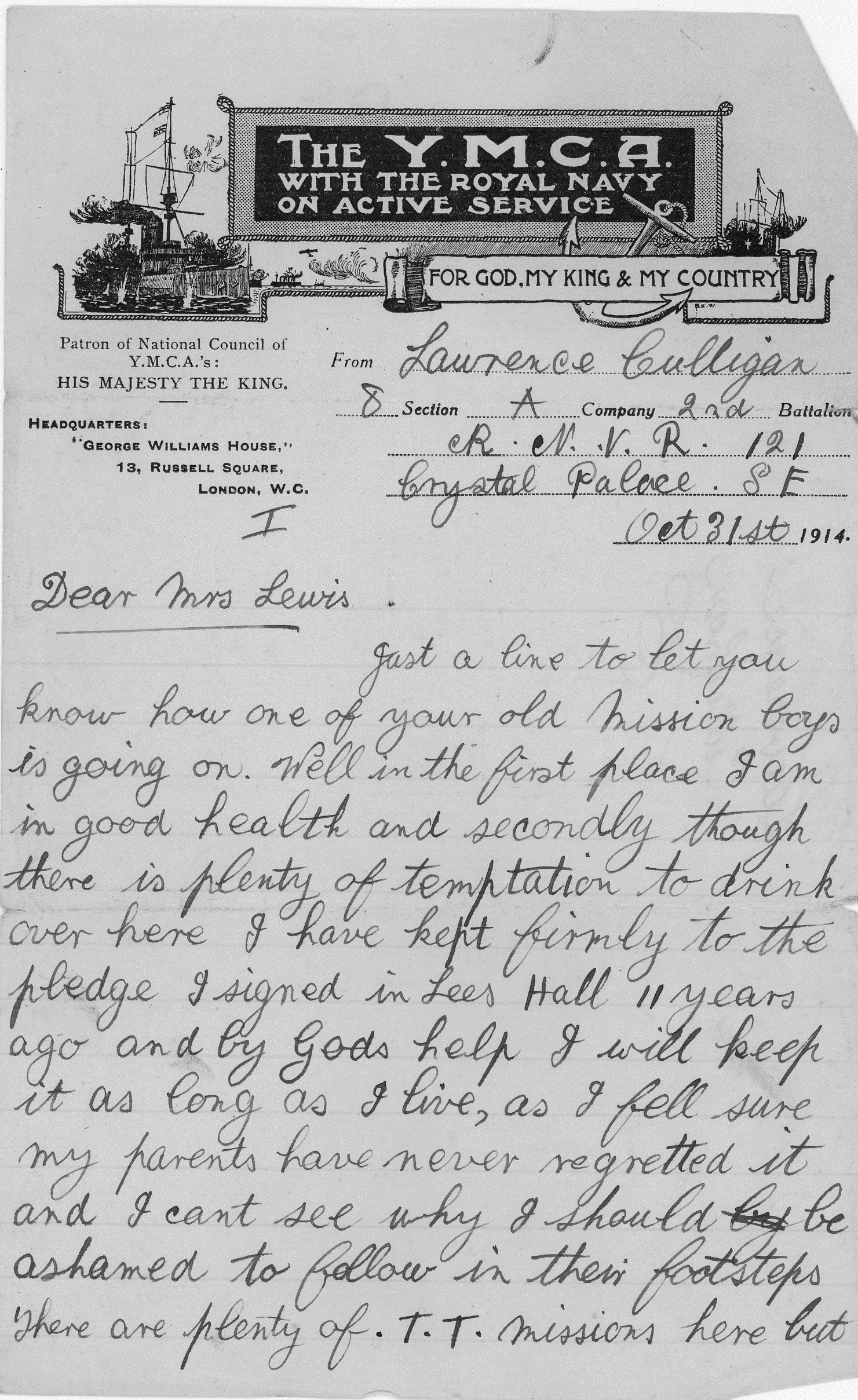

James Cunningham was elected Mayor of Blackburn in 1859, having spent many years building up his reputation and social standing in the town.

He first came to Blackburn in the 1820’s from the Scottish borders (where exactly we are unsure of)* to work under service as butler to William Feilden at Feniscowles Hall in Pleasington. As a Conservative Member of Parliament William Feilden would frequently travel to London with his butler on matters of Parliament. It is during this time that Cunningham was able to build on his passion for politics and observe the etiquette of the upper class.

During his time in service with the Feildens James Cunningham built up a tidy savings account, and after 30 years as butler he left the household in 1836 and bought a brewery close to the town centre, called Snig Brook Brewery, just off Montague Street. Using the business and social skills learnt from his employer James Cunningham was able to build up the brewery, and in turn established himself as a successful business man in the town. His success as can still be seen today in the form of (what is now) St Pauls Working Mens’ Club on Montague Street, the residence Cunningham built for himself with the profits from the brewery, an achievement he was very much proud of. It is an impressive building, built to show the wealth of its owner.

Due to his success as a business man in the town, James Cunningham was able to enter the town council as a representative of the St Paul’s ward, the area in which his home and brewery were situated. He was able to move further up the social ladder, due to the backing he had from the Liberals, to become first an Alderman (a body of people in aide to the Mayor with a legislative function) and later in November 1858 he was elected Mayor.

It is certain qualities in his personality that enabled Cunningham to achieve the title of Mayor of Blackburn. He was a popular man not only with the upper classes of Blackburn, due to his interest in politics and success as a brewer, but also with the poorer classes to whom he was able to relate. He never forgot where he came from, and had experienced first hand the restrictions that came with being poor. He was passionate about improving services and conditions for the poor in Blackburn. For example, his biggest achievement as Mayor was to open a free public library, spending £150 on books. This gave the under educated poorer classes an opportunity, usually restricted to those with money, to learn to read and expand on their knowledge.

James Cunningham was an inspirational man, building up his success and status from butler to Mayor through determination and his passion to help. He was a very social, laid back person with a good sense of humour and a happy demeanour which made him popular with everybody he met. For example, even after quitting politics the Conservatives re elected him as Alderman in 1865, achieving the largest number of votes of any Alderman ever elected. He used his success, popularity and wealth to help others all throughout his life. He was a big donor and supporter of the Widows and Orphans Fund who in 1873 awarded Mr Cunningham the title of ‘Loyal Order of Ancient Shepherds, Widows and Orphans Fund’. It was said of him during the presentation of this title

“You have been a father to the fatherless, you have caused the widow to wipe away the tear of sorrow from her eyes, and caused her to rejoice when she knows there was some one to watch over her little ones...”

James Cunningham died on 19th October 1876 in Lytham at the age of 80, having built himself up from butler, to alderman, to mayor and finally to county magistrate. His legacy was not forgotten. A portrait of Cunningham was hung in the Free Library and Museum, and still hangs there to this day.

Researched and written by Helen McFeely, volunteer at Blackburn Museum

* Although the books such as Abram’s Blackburn Characters claim he was born in Scotland, this is untrue. He was of Scottish descent, but was born in Haydon Bridge, Northumberland, his parents having moved there from Ayrshire. In 1866,he placed a stained glass window in the church at Haydon Bridge in memory of his parents Henry and Eleanor.

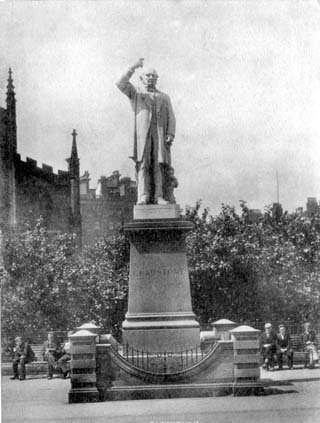

Why is there a statue of Gladstone in Blackburn is a question that is frequently asked. The'Grand Old Man' was not born in the town and never represented it. Indeed Blackburn was the first town in the land to honour the G.O.M. with such a monument after his death. To answer the question we need to look at Gladstone's career.

William Ewart Gladstone was born on December 29th 1809 in Liverpool, the son of a merchant. He was educated at Eton and Oxford where he won a double first. He was elected MP for Newark in 1832, the year of the Reform Act. He became a junior Lord of the Teasury in the short-lived Peel administration of 1835. In 1841 when Sir Robert Peel was again in power, he became Vice-President and then President of the Board of Trade. His instincts were becoming increasing Liberal however and in 1846 he left his Tory seat in Newark and became a Liberal MP for the University of Oxford.

When Lord Palmerston, the Liberal leader, became Prime Minister in June, 1859, he offered Gladstone the post of Chancellor of the Exchequer. Gladstone first became Prime Minister in 1868. He was to become Prime Minister again in 1880, 1886 and 1892. Extension of the franchise is ever associated with Gladstone's name, although it was Disraeli's 1867 Reform Act which had given the vote to every male householder. Gladstone though was a keen advocate for votes for working men, and it was this perception of him which established him as the champion of the people.

Gladstone's other great cause was Home Rule for Ireland, but Tory and House of Lords opposition frustrated all his attempts. Gladstone saw further than any of his contemporaries. He correctly forecast the consequences of the arms race that was a feature of the late Victorian age in Europe, but his warnings went unheeded and his own grandson was to die in the Great War that followed. He was an inspired speaker and his oratory attracted thousands to his open-air meetings. He was particular popular in the industrial areas of the North. His words went to the hearts of men and women who knew they hadn't much to expect from those in power. They knew he was different - a man of the people. He died in 1898, aged 88 and was buried at Westminster Abbey.

Blackburn's Gladstone statue was also its first one. A public subscription secured the £3,000 cost. Adams Acton, who had known Gladstone and created the statue of him which adorned Liverpool's St George's Hall, was the sculptor. The Earl of Aberdeen unveiled the statue on November 4th 1899 in the presence of 30,000 spectators. The statue originally occupied a site on the Boulevard and was there to greet Victoria when her own statue was unveiled six years later. However Gladstone and Her Majesty never got on. Perhaps she'd been jealous of the G.O.M's popularity. Certainly it was better for both when Gladstone was later moved to his present situation by the College; besides he was always, first and foremost, a man of learning.

Lancashire Leaders: Social and Political

Ernest Gaskell

Iron Master

Joseph Harrison was born in Ingleton in 1804. His father was a mining engineer. Joseph became an itinerant blacksmith and settled in Blackburn in 1826. He set up business in the old smithy in Dandy Walk, originally the smithy for the Dandy Walk factory set up at the beginning of the 19th century. After marriage to Elizabeth Hodgson he took up residence in Darwen Street.

Harrison specialised initially in wrought-iron work, manufacturing gates many of which could be seen in the town, eg the entrance gates to Sudell House in King Street. Later he established Bank Foundry at Nova Scotia and cast lampposts for the Gas Company and the town council.

Harrison became a councillor and alderman, representing St Peter's Ward. He moved from Darwen Street to Bolton Road and in 1847 to Galligreaves Hall, which stood then in its own grounds amid elm trees and extensive lawns. Later when streets and factories hemmed it in, it became a Conservative Club and later a public house. In 1862 Harrison bought Samlesbury Old Hall and restored it to its 15th century splendour.

Harrison's three sons had distinguished careers. Henry set up the Chamber of Commerce and his name will for ever be associated with the famous Mission to China in 1896. Joseph Harrison died on February 18th 1880.

With thanks to Jim Halsall for supplying resources.

The Story of My Life - The Rev Dr Nightingale

This is a series of three articles of the autobiography of Rev. Dr. Benjamin Nightingale (1854-1928) printed in the Blackburn Times on the 18th, 25th of February and the 3rd of March.

Introduction from the Blackburn Times:

A melancholy interest attaches to this series of special articles, of which the following is the first. Dr. Nightingale’s autobiography was written, and he himself despatched the MS. To “The Blackburn Times,” just before his last illness in December.

By arrangement with him publication was to have commenced the first Saturday in the New Year. His death led to its being suspended till such time as the wishes of Mrs Nightingale and her family could be ascertained.

If the story of his strenuous life shows other young people what can be done by faithful endeavour, and serves as a stimulant—phrases from his own letters—its posthumous appearance will have achieved the purpose Dr. Nightingale had in view.

1—BIRTH AND EARLY LIFE

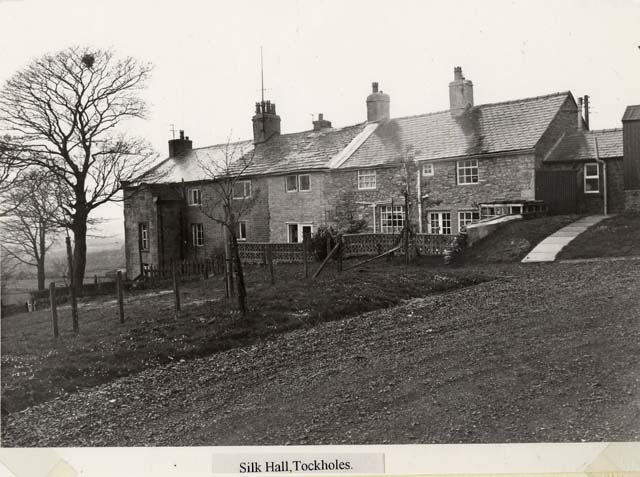

I was born on January 7th, 1854, in the little village of Tockholes, which lies some three miles from Blackburn on the old Bolton and Blackburn road. I am a little uncertain about the house. We lived for a time at Lower Hill in a simple cottage with a somewhat tall chimney, which was once seriously damaged by lightning; and from this place we removed to Silk Hall Fold, the top house near the main road; and I have always understood that this was the place of my birth.

My Fathers name was Benjamin, and the Nightingale family to which he belonged in all probability came from about Rivington near the middle of the 18th century. He was one of a numerous family, his father being William Nightingale, who was brought up at Lyons Den, a wild and desolate place on Darwen Moor Looking down the Tockholes valley. My Father’s mother’s maiden name was Nancy Grime, aunt to the celebrated Dr, Grime of Water-Street Blackburn. She survived my grandfather several years, and I remember occasionally seeing her. My grandfather left Lyons Den somewhat early and resided Sunnyhurst Wood, where he died comparatively young. The house still stands and is now used as a place of refreshment [see if it still there]. My father was just a plain working man, and for some time he travelled each day to his work at Darwen, and that at a time when hours of labour were much longer than they now are. I do not remember much about him, for he began to be seriously ill when I was very young and went for three weeks to the Convalescent Home at Southport. As I was also unwell at the time it was arranged for me to go with him, and I well remember the strange feeling I had when I saw a train for the first time in my life. Southport also was very different from what it is to day. The visit did me great good but my father none, and he died after much suffering on January 26th, 1865, at the early age of 45, when I was just 11 years old.

My Mothers name was Agnes Brindle daughter of John and Agnes, who lived at Lower Wenshead. The Brindles like the Nightingales, were an old Tockholes family and very numerous about Darwen and Blackburn in later years, as well as Tockholes. Agnes Brindle, my grandmother, was a Hawkins before marriage, and so connected with the Hawkins of Preston; the Brindles were also connected with the Higsons of Blackburn. According to stories circulated in the family, my grandmother was a most remarkable woman. It is said that she had twice and twenty children (a common expression about Tockholes, meaning 22) of whom two were born on the same day, and two were buried on one day. Four of her daughters married six Nightingales and, late in life, for some reason she had her leg amputated and was provided with a wooden one from an apple tree, the pip of which, after the apple had been roasted, she had set in her young days. I never knew her, for she died for she died on February 7th, 1853, at the age of 69 years. Nor did I know my grandfather, John Brindle, who died on July 2nd, 1849, aged 66 years. My mother survived my father many years, and late in life married my father’s brother, James Nightingale, whose previous wife was Nancy Brindle, my mother’s sister. He was at the time living at the farm at Silk Hall Fold, belonging to the Congregational Church, and my mother and I went to live there. My mother died in April 1881, and was interred in the graveyard of Tockholes Congregational Church. She made no profession of religion, but she was a good woman and most devoted to her children. Unless something absolutely prevented, she was never absent from the service on Sunday afternoon.

SCHOOL MASTER’S WILLOW STICK.

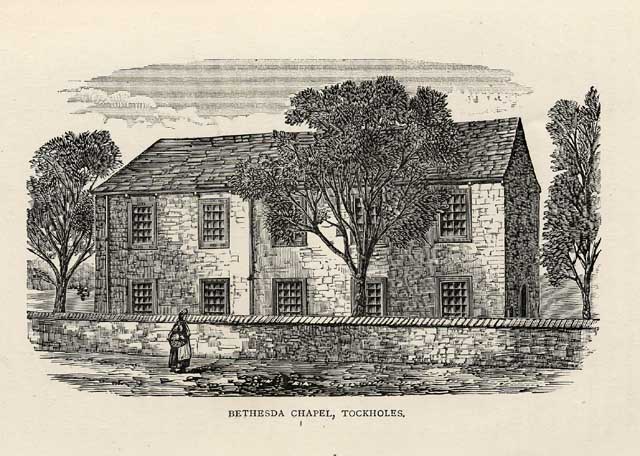

My early life was exceedingly simple and primitive, for in those days the village was very far removed from the town, and weeks and months might pass without a fresh face appearing in it. Darwen and Blackburn Fairs were red letter days in the year, when occasionally one had the privilege of going and, with a sixpence in ones pocket one felt rich beyond compare and able to buy nearly all in the fair. The day school I attended was as primitive as all else. It was a simple structure at the back of the Bethesda Chapel, in a somewhat dilapidated condition, which was said to have been the manse when that place had its own minister. There were two rooms below, the one behind being unflagged as was the case with many cottages, and called “The Shop” because there the handloom weaving was done. The teacher was Thomas Nightingale, who was one of the great men of the village, being a deacon and a choirmaster of the church, and indeed, general leader of the place, who invariably conducted the weeknight service when there was no minister and frequently occupied the pulpit. The three R’s only were taught there and those only to the very elementary stage.

A picture of the school, which was well attended, rises before me as I write. An old well spectacled man, with a long white beard, smoking his pipe, is sat before the fire in a in a broken down fireplace. In his right hand is a long willow stick and at his side a boy “saying his lesson.” While this was going on the rest of the children were left to themselves and, as may be expected, often became very noisy, with the result that the willow stick would unexpectedly descend upon them. Some would steal away into the shop and play at marbles until willow stick appeared, and others would slip outside and the spacious grounds around, where grew many trees, in the time of autumn would gather the fallen leaves for a bonfire, until again willow stick appeared to cut short their joy. I was all very primitive, and will doubtless amuse those who have educational advantages of today, but it was the only education that not a few ever had, and the old teacher was held in revered memory by those who were privileged to sit at his feet.

Quite a number of “half timers” came from Hollinshead Mill, then belonging to the Shorrocks of Darwen and in the village it needed little education to mark out a boy or girl as remarkably clever. The people would say with astonishment, “He con read th’ Bable an’t newspapper.” After a time the school was given up, and being then a half timer at the mill, for a short time I attended the one belonging to St. Stephen’s Church, whose teacher was Mr. George Slater, who lived in Blackburn during his retirement.

A WATERLOO VETERAN.

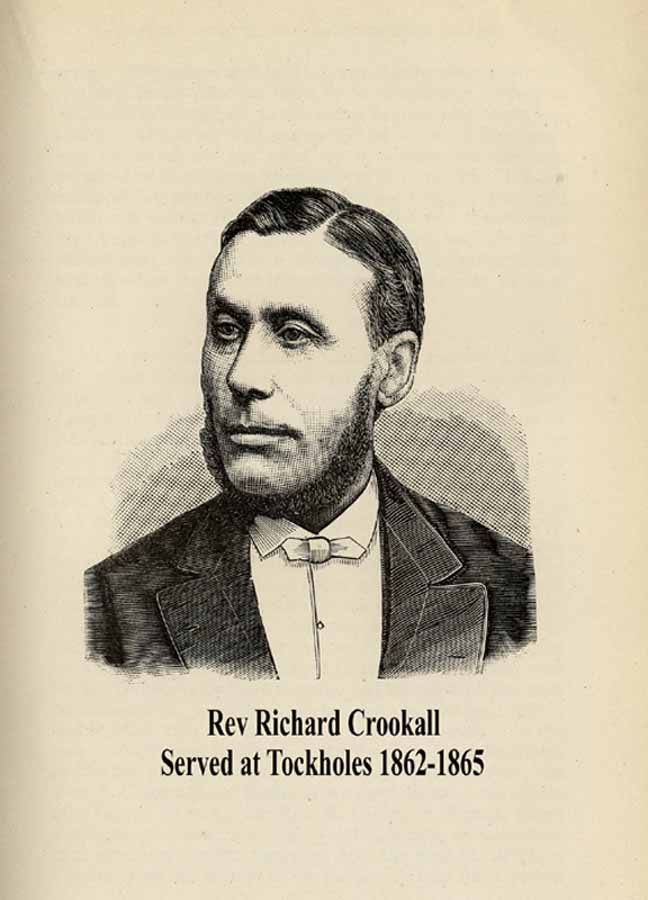

I have a very vivid memory of the Cotton Famine in 1862, though I was only eight years old. Lancashire was never more hardly hit, and the suffering of the people was very great. Many indeed, who had moved in spheres of comparative comfort, were utterly reduced and some carried to the grave burdens of debt then contracted. Tockholes, which was largely dependent on its two mills, suffered as did many other places, and soup kitchens and food stores were opened. The vicar, the Rev. G. Hughes, BA, and the Congregational minister, Rev. Richard Crookall, worked heartily together in the endeavour to relieve the distress of the people. Young as I was, I well remember spending days in travelling with my elder brother, William, in search of work to no purpose, and the rejoicing was great when the famine ended and the people again got to work. It was thought at one time, with a view to finding employment for the people, that an attempt would be made to level the Morris Brow, which has always been a serious difficulty for vehicular traffic between Blackburn and Tockholes, but the idea was abandoned as much too costly for the authorities to face.

There were several curious characters in the village, one of whom went by the name of “Owd Kester o’th cloise.” He was of great age and was a Waterloo veteran. He was accustomed to go round the village selling small articles and very few dared to refuse to buy. He was regarded by the people as the centre of much mystery, as he told strange stories of his doings when he was in the army.

I do not claim to have been any better than other boys of my age but it is only truth to say that I was happily saved from falling into evil habits not uncommon. In this connection I recall an experience that marked a critical moment in my life. At one place in the village, a person had recently opened a sweet shop and started a lottery, and not a few of the boys spent hours there gambling in a small way. I went one Saturday night and played a considerable time, with what result I cannot say, but I was not easy whilst I was there. The company was not quite to my liking and I vowed that I would not go again. The vow was kept and I often thank God that it was, for of those who frequented the place few made anything of life.

When I was quite young, not more than 10 years of age, I began to go to the mill. There were two cotton mills in Tockholes. One which went by the name of “Redmayne’s Mill” was built about 1838 by the Redmayne brothers, who had connections in both Blackburn and Preston. This subsequently passed into the hands of Henry Ward, of Blackburn and in my young days it was at its best. The other was built by Eccles Shorrock of Darwen in 1859, being known as “Hollinshead Mill.” It was here that my elder brother and I worked, and in those days working hours were much longer than they now are and the conditions much less Favourable. This mill later passed into the hands of Messrs George and Ephraim Hindle, of Blackburn. Both buildings have now disappeared, but in those days some two or three hundred people were employed in them and they were a great boon to the village.

About this time also there was a considerable amount of handloom weaving in the place the looms being in that part of the house which has already been referred to as “the shop,” and often far into the night and even into early morning the candlelight’s might be seen twinkling in the windows, the weavers being anxious to finish their pieces so that they could take them on the Saturday to Blackburn to those who employed them. Not infrequently the weavers kept time with the shuttle by singing some well known hymn, and it is said that a certain Darwen minister, who late in life gave himself to handloom weaving, used to sing “Oh what heavenly work this is, hands, feet and arms singing praise to the Lord.”

Shut in within themselves and having so little contact with the larger world outside, it is no wonder that superstition lingered long in these villages and Tockholes was no exception to this. Linked with almost every house of any age was some ghost story which was seriously believed by the people. There was a least one family also that had that had the highest veneration and reverence for the cricket. It was known that there was a considerable colony in the house, for the chirpings could be heard in the road some distance away. Along with some of my school fellows, I had been anxious to get a sight of this mysterious creature, as to whose strange powers many stories were in circulation. One day, therefore, we went to the house and preferred our request. We were informed that we might see the crickets on solemnly promising not to injure one of them, the person adding that for some years ill-luck had attended the family in the way of sickness and death because some time ago one of the crickets had been killed. The promise was of course given and we were admitted to the house. The hearthstone was carefully lifted and under it must have been hundreds of them, which were as carefully protected as if they had been so many guardian angels. Doubtless this was an exceptional case, for I cannot recall any other at all corresponding to it.

FAVOURITE READING.

Nearly all the people were at the same social level, farmers and artisans, simple in their habits and plain of speech, which almost without exception was the Lancashire dialect. If anyone happened to go away for a time and on his return attempted a little more refined speech it used to be said, with not a little surprise: “Eh, mon, he tries to talk fane.” In my early time I gad a somewhat serious illness which greatly reduced me. Its precise nature I do not know, for in those days doctors told their patients less about their ailments than they do now; but I vividly recall how, when walking about the village, women in particular would say even in one’s hearing: “Poor lad, he’s nod long to be here, he’s goin’ whoam fast.” How mistaken these good friends were, who were quite sympathetic in their remarks, my present years testify. The Rev A.M. Davis, who exercised a great ministry in Oldham extending over 50 years and whose training was received at Blackburn Academy, used to tell a similar story about himself. When he settled in Oldham, some of the people said that the thin, pale-faced young man was suffering from consumption and could not possibly live long. When he was over 80 Mr. Davis, relating the story, jocularly remarked: “I am consuming yet.”

I was always fond of reading, but in those days books were expensive, and for country lad money was not plentiful, consequently my library was very small. My favourites, however, were Robinson Crusoe, Captain Cook and Robert Bruce. My heroes indeed were Bruce and Wallace, and it may not sound very patriotic when I say that I rejoiced exceedingly when I read of the defeat of the English at Banockburn by my great hero, Bunyans “Pilgrims Progress” was my daily companion. I read it over and over again, told the story to my companions as we went together to our daily work, and often wished it had been literally true instead of allegorical, so that I might take a similar journey.

I was also greatly interested in missionary stories, which were often most exciting; for in those days the romance of Christian missions was at its height and “The Juvenile Missionary Magazine” was my great delight, which has been long extinct for many years read every sentence in it, long preserved and treasured the copies and often felt that I would like to live and work in those strange and distant lands with which they were concerned. So my young life went on happily in the little place which was not much longer to be my home.

Religious Decision And Preparation For College.

One of the chief centres interest in the village is the little Congregational Church whose history reaches back at least to “The Great Ejection” of 1662. Linked with those early days especially, is a great deal of real and most wonderful romance. The people were of a strong and sturdy type, faithful to their religious principles when there was considerable risk in being so, and tradition tells how they used to meet in secret places, of which there were many in the neighbourhood, and hold their meetings, when nonconformity was a forbidden thing. The history of this little church was written by me over 40 years ago. It was my first literary venture. For more than two and a half centauries it has kept the light of divine truth brightly burning in the village, and sent to the neighbouring towns of Blackburn and Darwen many who have been among the most devoted and earnest workers in the churches there. In the long line of men who have served in the ministry there are several who rank among the most distinguished men in Congregation history.

About a hundred yards away from it was Bethesda Chapel, built in opposition to it in the early part of the 19th centaury. It never however was a great success, and had only one minister. After a time it was acquired by the other people and became the Sunday school. It was a large building in quite capacious grounds, where many trees grew, which served as a graveyard. It was to this building that the manse was attached, where the day school already named was held.

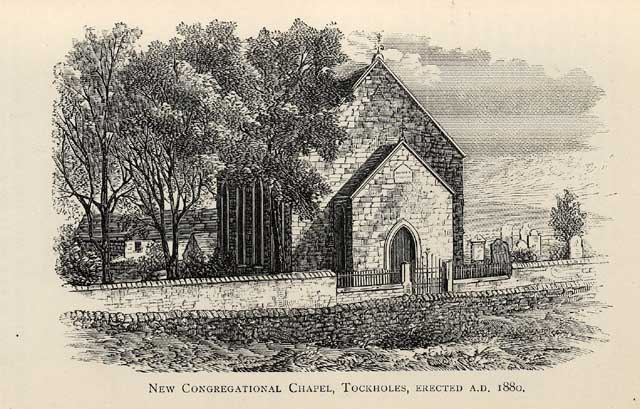

At Silk Hall was a large room over the farmhouse; that was used for weeknight services, tea meetings and Sunday evening services. Attendance at both school and church was part of the Sunday programme, which could no more be set aside than breakfast or dinner, and I often feel very thankful that it was so, and that from my earliest days the habit of attending school and church was formed and never broken. It was the old chapel that I attended, the chapel of 1710, which continued until 1880

When it was superseded by the present handsome structure on its site, and as I write, the place as it then was comes vividly before me

THE CHAPEL OF 1770.

It was galleried on three sides, the pulpit being on the fourth and almost within reach of each gallery. The pews were straight backed and ours was in the gallery to the right of the preacher. The place was well attended and many good, earnest, devoted families were represented, such as the Gregsons, Smiths, Leighs, Sumners, Worrsleys, Whipps, Nightingales, Brindles, Fowlers, Richardsons, Kershaws, Dewhursts, Aspdens, and others. The earliest minister of whom I have any recollection was the Rev. C. Bingly, who was the earnest and most devoted man. As he was there only four years and left for Droylsden in 1857, my memory of him is very faint; but an incident occurred which made a deep impression on my mind, young though I was. Some part of the time my mother was seriously ill in bed and Mrs. Bingley came to see her and on leaving sprinkled something on the bedclothes which, I thought made her well again. Then, for another four years the Rev. Horrocks Cocks held the pastorate. He resided in Blackburn part of the week and the other part at the manse at Silk Hall. He will be remembered as Editor Of the “Blackburn Times,” which was just entering on its career. He was a somewhat eccentric character and always began the Sunday morning service with the same hymn, “Sweet is the work my God, my King.” In his later years he resided in London and, when I was writing the Tockholes history, I had much interesting correspondence with him. The Rev Richard Crookall followed, and as already noted, he was here during the cotton famine, [see part one] and did great work in connection with it. He was a most impressive preacher, and his appeals, to the young in particular, were often most effective. I have a vivid memory of one such appeal, when he was speaking on Absalom at a cottage meeting at the house of Mr. Whipp, New Barn. He remained only a little over three years and removed to Northallerton, in Yorkshire.

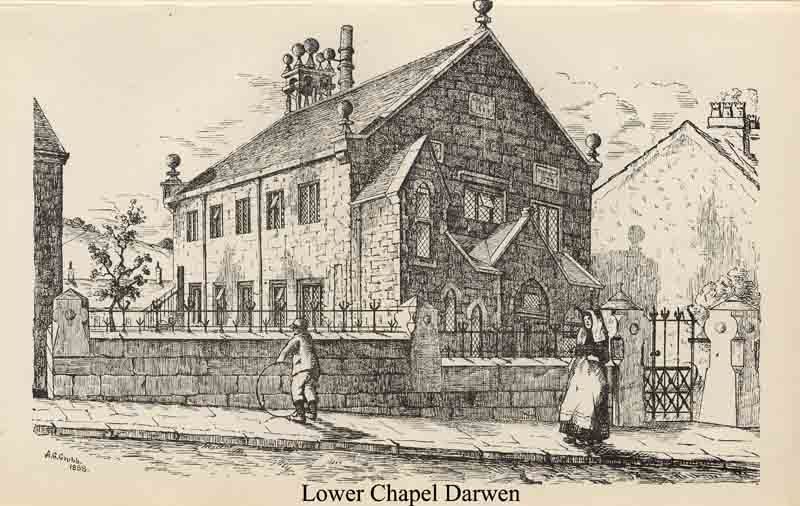

During the frequent vacancies the pulpit was occupied by various persons, ministers and laymen. The Rev Wm. Hodge, of Bretherton, was quite a favourite and he scarcely ever preached without shedding tears. Mr. Hoole, once connected with Blackburn academy, and who subsequently had an important school in the town, was another. He, also, was most pathetic in the pulpit, suggesting a very tender disposition, and I remember him once telling one of his old pupils about this, who smiled and said that there was little evidence of this in the classroom. The Rev. G. Berry, of Lower Chapel Darwen, was noted for the way in which he divided his sermons into “generals” and “particulars.” I have heard him give half a dozen generals and as many as 19 particulars, yet his visits were always welcome. One gentleman who came from Preston whose name I never knew, a layman, had a rather bad time. There was one boy in the gallery who was sometime unruly, and in the middle of his sermon he stopped and said quite sharply: “take that boy out, he has been a naughty boy for some time.” The incident made a deep impression on my mind though I was very young; I did not in the least justify the boy, but the preacher lost all his power over me and through all my ministry, whatever provocation I may have had in any service, I have never permitted myself to call attention to it by any remark from the pulpit.

A Startling Apparition.

Another gentleman, also a layman from Preston, put on rather amusing airs. Referring to the mouth of the River Nile, in slow, ponderous tones, he said; “For-r-mingh a large del-ta covered by a multi-tu-dinous number of stones-ah.”

As already stated, the Sunday school was in Bethesda Chapel in my day, though it also has given place to finer and more convenient structure at the top of Silk Hall Fold. The school was exceedingly well attended. The teachers were simple, earnest, devoted Christian men and women without any scholarship, but full of zeal for Christ. One of my later teachers was James Fielden, whose lessons betokened great preparation and study. For one while he lived in Blackburn, but he never failed his class and his scholars were greatly attached to him. To this good man, who still resides in Tockholes, I owe much, and I often feel grateful to god that it was my privilege to be a scholar of his.

One curious incident in the school life is worth relating. The superintendent was Thomas Nightingale, who has already been mentioned [see part one] in connection with the day school. One Sunday afternoon when opening the school he intimated that one of the scholars, well-known to all, was seriously ill, lying in deed at the point of death, concerning whom there was little hope of recovery, and the sentence had barely left his lips when, to the surprise of all, the scholar in question walked in to the school, comparatively well again.

In 1867, when I was just entering upon my teens, the Rev. John Robinson, from Tosside, near Settle, came to be minister and it is to him that I owe my decision for the ministry. He was an untrained man, one of several prepared for the ministry by the Rev. Joseph Wadsworth, of Clitheroe, and a most earnest and faithful preacher. I have often felt that had he had the training that men get to-day, his preaching power was such that he would have occupied a prominent position in the denomination. Very early in his ministry I began to be seriously impressed, and from about 14 to 16 years of age may be said to have been under religious impressions. Sometimes they were stronger than others, but they were always there, and I passed through much before peace came. Bother minister and teacher tried to help me, but seemingly to no purpose. A book was put into my hands, “The touchstone of sincerity” by John Flavel, an old Puritan Divine, but it was hardly the book for me at the time for tortured me with doubts and fears. Bunyan’s “Pilgrims Progress,” his “Holly War” and other works of his were read in the hope that light would come, but it held back.

A SACRED PLACE.

A little place attached to the barn at Silk Hall Fold is still very sacred to me, for there in the darkness, after returning from my work at night, I often poured out my soul in earnest supplication to God, and the ecstasy of the moment, when I felt that Jesus was my Saviour is still with me. Shortly afterwards I was received into the fellowship of the church.

Mr. Robinson was a particular fond of Nonconformist history and almost worshipped the Nonconformist heroes of bygone times. I recall visits paid to our home when he told exciting stories of Oliver Heywood, Isaac Ambrose, Thomas Jollie, the Pilgrim Fathers, and the sufferings of the early Christians in the Catacombs of Rome, all of which fired my young heart. Doubtless in part at least, those visits, as well as my connection with a church which had such a glorious history, are responsible for the form which my studies have since taken. Mr Robinson left for Ramsbottom in 1873, and subsequently was at Elswick in the Fylde district, a church whose history reaches even further back than that of Tockholes and whose career has been equally honourable and great.

Shortly after admission to the church I began to do Christian work. In particular I became teacher in the Sunday school, occasionally engaged in prayer at the weeknight service, and eventually Mr. Robinson spoke to me about the ministry. He asked me if I felt at all inclined towards it. There was no pressure of any kind and I was left to consider the matter for a time. There was one difficulty in the way. I was already engaged to Miss Sumner, my faithful, and devoted wife all through life, the representative of an old Tockholes family, and who attended the same church and school as myself. In case I went to college, which was what Mr. Robinson suggested, it meant postponing, considerably, our marriage day. When, however, I mentioned the matter to her, I found that she was not only willing but most eager for me to do it, and when next I saw Mr. Robinson I gave him my decision accordingly. He promised to give me what help he could in providing opportunities for Christian work, and occasionally I was called upon to open the Sunday school and take the introductory part at cottage meetings. Mr Robinson suggested that I should go to Nottingham, but being an untrained man himself, he could give me very little help in preparing for this

GREEK STUDIED AT THE LOOM.

I began the study of Greek and used to take my book with me to the mill, snatching occasional minutes to look at it. I was a four-loom weaver; the working hours then were from six to six o’clock, and, as I had over a mile to walk each way, it meant from 5.30 to 6.30. On arriving home at night, after a simple meal, I went into my little bedroom to study and often remained there until one o’clock in the morning. The little window of the room where this was done looks out upon the Fold and I never see it without vivid memories of the struggle of those days. My mother, who was most devoted to me and eager to help me all she could, used to waken me at five in the morning, and this I did for quite three years. I saw, however, that some further help than my life in Tockholes promised was necessary and I resolved to go Darwen to live with my brother William at Hollins Grove. He was an overlooker at Eccles’ Mill, and work there was secured for me. I often vividly recall the day of my removal: it was a most trying experience. I had never really been away from home before; it was the opening of a new chapter in my life history. As already noted, my mother had been married to my uncle James, [see part one] but I felt greatly the wrench from her and the old home. I took the way over the Winter Hill carrying in a parcel a few of my belongings. When I reached the top, I looked behind it, the dear old home that I was leaving forever and before me at the town of Darwen in the Valley, a sort of mystery land, and though I was then a young man, I wept tears of deep sorrow. My life in Darwen was not very eventful. I joined the Church of Belgrave, of which the Rev. James McDougall was pastor, and attended the young men’s class there, of which Mr Nicholas Fish was the teacher. He was an able man and many of the young men subsequently rose to promise in the town and held impotent positions in the church. Mr McDougall gave me such help as he could, but he was to busy a man to do much. He got me my first preaching appointment, which was at the little chapel at Wiswell, near Whalley, which as since been replaced by the church at Barrow. The building, which has been turned into cottages, will always be. Sacred to me, for there I took my first full service and preached my first sermon. I remember well the time. The leading man there was Mr Hugh Harrison, a most devoted Christian worker, who always took a great interest in me. My sermon was on the text: “What think ye of Christ.” (Matt.xxii, 42.) I had quite a good time and was so delighted with the opportunity of preaching that I refused a fee, even travelling expenses, and thought I ought to give the people something for the privilege of taking the service. By a singular but happy coincidence, the cause at Wiswell was originated and the chapel built by a relative and namesake—Rev. Benjamin Nightingale, who was subsequently minister at Ramsbottom.

College Life.

After some nine months, I made application to Nottingham Institute, now Paton College, and was admitted as a student in the autumn of 1873. I well remember meeting the committee, before being accepted, when one member asked if I done much preaching. I had to admit that I had had little opportunity of doing so. “How do you know that you can preach then?” Was the swift and somewhat stern question which I thought sealed my fate. He was one of the College lecturers, and in reality a kindly old man whom I afterwards learned greatly to respect; but the question was harsh and harshly put, and the situation was saved by Dr. Paton, who put in the plea for me on the ground that opportunities for preaching had been lacking. The course then extended to three years only, and it was intended for men who were either too old to take longer training or whose educational equipment was to imperfect to promise much success in a longer college course. The English tutor was the Rev. F.S. Williams, and very elementary was some of the work we did with him and, of course, it needed to be to meet the requirements of the men. Theology and New Testament Greek were taken by Dr. Paton and we had lectures on ecclesiastical history by the Rev. H.F. Ollard.

We lived in private house, and where I was were two others. The institute was then in a most flourishing condition and the number of students was about 50. With the exception of several Scotchmen there were few men from the north; mainly they were from the midlands and the south, and the two or three who, along with myself, came from Lancashire were always betrayed by their northern accent. On one occasion in the sermon class, which was exceedingly good, one of the seniors, a Lancashire man, gave his lecture and I was selected by the principle to write a critique on the words, style and pronunciation. This I did, and his Lancashirisms were singled out for special comment. Dr. Paton greatly enjoyed it and said how true it is; “Set a thief to catch a thief.” Once a month we had the communion service on Monday afternoon, when Dr. Paton gave a short address, and every other Monday afternoon there was a prayer meeting. Those were very sacred and helpful gatherings.

Vacation Experiences.

Connected to the institute were several mission stations, and every student was on one or more of these missions, which he attended once a week as well as Sunday if not preaching elsewhere. The afternoon was spent in visitation and in the evening a service was held. Thornwood Lane Hucknall and Arnold were the stations with which I was connected, and the training which those mission stations gave was in every way excellent. Then we had a supply list which some times took us long distances and provided us with most interesting experiences. One place which was quite a favourite with the students was Helpringham, in Lincolnshire, where I preached more than once. There was a kindly old man there who, when the holiday drew near, used to speak of the vacation as the “vocation.” He always wished us a good time during the “vocation” and said he would welcome our return. Long journeys on foot, a seat in a milk cart or a market cart were not uncommon experiences in order to reach the little villages which were often miles away from any town.

During the vacation I returned to Darwen and usually had several preaching appointments. Blacksnape, which recently celebrated its centenary, and Bolton Road School, now represented by the fine church somewhat lower down, both connected with Belgrave, were places where I frequently conducted services. It has already been stated that Mr. Robinson came to Tockholes from Tossside, a country district a little beyond Clitheroe in side the Yorkshire border, and by his kind ness I was able to spend a week there talking two Sundays and visiting the homes of the people during the week, besides conducting cottage meetings.

I had now been at Nottingham a little while and I thought I knew all the theology that was to be known, or at any rate that was necessary, but hear I was disillusioned. I had heard of antinomianism, but here I was brought face to face with it in its most pronounced form: At the cottage meeting on the Monday evening some of the leaders of the little church spoke to me about a good man who was of that way of thinking, and who had been at the services on the previous Sunday. In the midst of the conversation there walked quietly in a certain individual, and the conversation immediately dropped. I did not, of course, know him, but by a kind of instinct felt that that this must be the person in question. I went on with the service, gave a short address on “There remaineth therefore a rest to the people of God” (HEB. Iv 9), and at the close intimated that the heavenly rest was open to all who believed in Christ and accepted Him as Saviour.

Dr. Paton’s Influence.

I was advised to pay a visit to the person in question the following day, and we soon got on his favourite theme. I found that he knew his bible well; at least all those passages that were supposed to uphold his views were at his finger ends. He referred to the service of the previous evening, and said it was quite good until I got near the end, where I spoiled all by offering the heavenly rest to all. “What business have you to do that?” said he. “Only the elect and chosen few will enter there.” In further conversation he said that there were “infants in hell a span long.” It was perhaps a little presumptuous for a young man, but the only thing I could say that served to move him was; “Are you a married man and a parent?” He replied in the affirmative. “ I should shudder.” I said, “to be a parent if I knew that some of my children were doomed to perdition.” It was altogether a most interesting experience and quite a revelation of what strange things men may believe, and that with a faith that scarcely anything can shake.

It was Dr. Paton’s custom in those days to select men from his students who were sufficient young, and who gave promise of fitness for a longer and severer academic training than the institute offered, and to send them to some other college; and to my surprise, after I had been there almost 12 months, he made choice of me with one or two more. It was, of course, a distinct honour, but there were some difficulties in the way and I laid them before him. He was exceedingly kind and sympathetic, but he assured me that if it could be done it would be of immense service to my future career. I eventually gave my decision in favour of his suggestion. The choice of college was not easy, for there was considerable suspicion of heterodoxy in relation to most of them. Dr. Paton’s own preference would have been in favour of Spring Hill, but he was not sure of it. Being a Lancashire man I was anxious to go to a Lancashire college, but it also was suspect. My pleadings, however, eventually met with success and the rest of my time At Nottingham was occupied almost entirely with preparation for entering therein.

My Life at Nottingham extended to two years and they were exceedingly happy years. I have often thanked God that it was my great privilege to be under Dr. Paton for so long a time. He was in every way a great man, a distinguished scholar and a true Saint, and his influence upon his students was deep and lasting. He more than once visited me for special services after I entered the ministry, and those visits are a most precious memory, for whilst he was perfectly human he was like an angel in the home. It is interesting to remember that a brother of his, the Rev. R.B. Paton, BA was for some time minister at Park Road Blackburn.

Back To Lancashire.

It was in the Autumn of 1875 that I entered Lancashire College, being one of 13 admitted at the time, the largest number known to have been admitted at once, and bringing the number of students in the college up to about 60, the largest number ever in college either before or since. The principle was the Rev. Caleb Scott, BA LLB (later Dr. Scott). He was most devoted to his work and no student in the college ever surpassed him in that respect. That indeed, was the one thing about him that always impressed the students. Whoever might be slack and indifferent the principal never was, and his lectures always indicated the most careful and through preparation. He took Theology and New Testament Greek. The arts were largely in the hands of Dr. Hodgson, a most genial kindly man whom the students greatly loved. Some times, I am afraid, his good nature led to liberties being taken with him. Dr. Thomson, minister of Rusholme road Congregational Church, gave assistance by taking the Hebrew class. He also was a dear soul, knew his Hebrew Bible from cover to cover but there few men whom he filled with the enthusiasm for the Hebrew language which was his own. During the arts course we went several times a week to Owens College. The University had not then come into existence, and among the men there of whom I treasure any sacred memories was Dr. Wilkins, Who took us in Latin. He knew his subject perfectly and had an interesting way of putting it before his students. Dr. Wilkins was a Congregationalist and attended Rusholme Congregational Church, then under the pastoral care of Dr. Finlayson. Later he was called to the chair of the Lancashire Congregational Union, and by a happy coincidence delivered his presidential address in Cannon Street Church, Preston, during my pastorate there.

Hard Study.

Life at Lancashire College was very different from what it had been at Nottingham. For one thing we all lived in the college and consequently saw sides of each other’s life and character which we had no opportunity of doing at Nottingham. Then there were games of various kinds: cricket and football in their respective seasons, and many a stiff game at “Rugger” come vividly before me as I write. I am free to confess that in my early days there, so different did the men seem from what I had been accustomed to see at Nottingham, that I was occasionally shocked, but I came eventually to see that nothing was lost by keeping alive the humorous side of life. Then I was thrown into contact with men whose educational advantages had been so much greater than my own, who all their life, almost, had been in training in good schools, which made work for me exceedingly hard, and often necessitated long hours of study. We had also quite a brilliant set of men in college at that time, among them Arthur N. Johnson MA, for many years Home Secretary of the London Missionary Society, whose father, Rev. G.B. Johnson was for some years minister at Belgrave, Darwen; W.H. Bennet. MA Litt. D, who subsequently became principle of the college and who stood in the forefront for his scholarship and learning; T.K. Higgs, MA, who for a time was minister at Greenacres, Oldham; and J.R. Murry, MA, who after long years secretary ship of the Church House, Manchester, is leaving for Church Stretton, in Shropshire. I entered college at a time when Dr. Scott was most anxious to do degree work, and whenever possible a man was sent in for matriculation. Almost the only degree open to us was that of London University, and at the end of the first year I sat for matric. With several others, but few of us got through. I tried again the following January, having to go up to London for the purpose, and this time managed to pass in the first division. The certificate is date February 13 1878. An interesting experience occurs to me as I write, which is worth relating. I had been brought up in a somewhat strict school, and among other things had been taught to shun novels as dangerous and wicked things. I must have read many a bit of fiction but I had never knowingly read a novel proper. One of my fellow students urged me to read Sir Walter Scott, but I refused. He urged me, however, again and again, and at last I yielded, taking by his advice “The Heart of Midlothian,” I was delighted with it and followed on with “Ivanhoe,” which completely fascinated me. I kept on until I had completed the whole series. One of my fellow students, whose study was beneath mine, used to tell how anxious he got about me when he heard me up late. Thinking it was Scott with whom I was occupied he said, “He used to pray for me.”

My course at Lancashire College was considerably shortened owing to my previous Nottingham training, and in the spring of 1878 I accepted an invitation to the pastorate of Townsfield Congregational Church Oldham. At Lancashire, as at Nottingham, my life was very happy and I often think with gratitude of the distinguished men at whose feet I was privileged to sit.

by Stephen Smith

James Hargreaves was born near Blackburn at a farm on the moors above Oswaldtwistle (the exact location is unknown). Relatively little is known about his early life, apart from the fact that he was a handloom weaver, unable to read or write, but with an interest in carpentry and engineering. Details of his marriage and the birth of his children have been gleaned from the Parish Registers of Church Kirk.

In the 1760s Hargreaves and his family lived at Stanhill where they spun on a spinning wheel and wove on a handloom. James had a keen interest in streamlining the various processes used in the production of cotton cloth - his first innovations improved the process of hand-carding, where the tangled fibres of cotton are teased out between two hand-held combs. Hargreaves' 'stock-card' featured a wooden bench or 'stock' covered with carding wires, which allowed far more cotton to be carded by one person at once.

However, James Hargreaves' most famous invention was the Spinning Jenny, a machine which took the traditional spinning wheel and turned it 90 degrees to a horizontal position, allowing it to spin multiple spindles at once. Debate still rages as to the origin of the name 'jenny'. It is often claimed that Hargreaves' daughter Jenny knocked over an old spinning wheel one day, giving James the idea for his machine - sadly, this is just a romantic myth: the Registers of Church Kirk show that Hargreaves had several daughters, but none named Jenny (neither was his wife). The word 'jenny' is in fact an early abbreviation of 'engine', simply referring to a machine or device.

The original machine was produced some time between 1764 and 1767. It featured eight spindles onto which the cotton thread was spun from a corresponding set of rovings (roughly spun cotton). This had a dramatic effect on the amount of thread that could be spun by a single person, although the early machines produced thread that was coarse and broke easily, only really suitable for the weft of a handloom (that which travels horizontally in the shuttle).

Hargreaves may have been a talented inventor, but he was not a shrewd businessman. He didn't apply for a patent for his Spinning Jenny until 1770, by which time many others had copied his ideas, reaping the rewards that were rightly his.

Although Hargreaves originally produced the machine for family use, news of his invention gradually spread across the industrial North. In Lancashire, traditional hand spinners saw the Spinning Jenny as a threat to their livelihood. They realised that the machine could produce spun cotton thread far quicker and more cheaply than their traditional method. An angry mob marched to Hargreaves' workshop, destroying his equipment and forcing him to leave the county. He moved to Nottingham and built a small spinning-mill, using his Jennies. Although this venture was not particularly successful, Hargreaves continued to refine the Jenny increasing the number of threads from eight to eighty.

By the time of his death in 1778, over 20,000 of Hargreaves' Spinning-Jenny machines were being used in Britain, but despite being credited with the invention of this remarkable machine, James only received very modest financial returns and died in relative poverty.

by Nick Harling

Stanhill Post Office

1753-1827

Inventor of the Spinning Mule

Samuel Crompton was another great inventor from the north-west whose ideas revolutionized the cotton industry, but who received little personal gain for his efforts. Crompton was born at a Bolton farm called Firwood Fold, but within five years his parents rented part of Hall i'th' Wood, a Tudor mansion now preserved as a visitor attraction.

As a youth, Samuel undertook various jobs including farmer, spinner and weaver, but he also displayed a keen and inventive mind as an accomplished musician and mathematician. As a spinner, Samuel had encountered Hargreaves' Spinning Jenny and Arkwright's Water Frame and felt that by combining elements of both (the rollers of the Water Frame and the twisting action of the Jenny), he could produce a much more effective machine. His first, hand-operated prototype was nicknamed the Spinning Mule, as it was a hybrid of the two earlier machines.

Almost as soon as Crompton had completed his first machine, he found himself in trouble with the local hand-spinners and handloom weavers, who saw any mechanization of the cotton industry as a threat to their livelihoods. In 1779, Samuel had to dismantle his machine and hide it in the rafters of Hall i'th' Wood in order to avoid the unwanted attentions of the machine-breakers.

When the threat of physical harm had passed, it became clear that Crompton's Mule would make a huge difference to the spinning branch of the cotton industry. Not only did the Mule produce a strong and very fine yarn, but larger versions, powered by steam engines, could spin thousands of spindles at once. Indeed, many cotton magnates built factories especially to house these very long mules.

Sadly, Crompton's precarious financial position at the time of the Mule's invention meant that he could not afford to apply for a Patent for his machine. Instead, he sold to rights to a Bolton manufacturer in order to raise some ready cash. In the long run, this move must have cost Samuel thousands of pounds. Despite a House of Commons award of £5000 for his invention (as late as 1812), Samuel Crompton's own cotton factory was a failure, and this great inventor died a pauper in his home town of Bolton in 1827.

by Nick Harling

1732-1792

Inventor of the Water Frame

Rather than being an inventive genius, Richard Arkwright was a sharp-witted businessman who recognized the potential of other people's innovations, and made a very large personal fortune from developing them. Preston-born to a very poor family, Richard was taught to read and write by a cousin, as his parents could not afford schooling. His first job was as a barber's apprentice. By 1762, he has founded his own wig-making company.

His first contact with the textile industry came during a business trip when he met the Warrington watchmaker John Kay, who had spent some time trying to perfect a new spinning-machine, but had run out of funds. Arkwright was very interested by Kay and his machine, offering to employ him and other local craftsmen to develop the invention. The resulting Spinning Frame could produce stronger thread than the contemporary Spinning Jenny, but was far too large to be operated by hand.

Arkwright and his team tried various experiments using horse-power, but the reliability and cheapness of water-power won the day. In 1771, Arkwright and his colleagues established a spinning and weaving factory on the banks of the River Derwent at Cromford, Derbyshire. The new invention became known as the 'water-frame'.

Thus established, Arkwright's mill required a huge workforce. He built numerous cottages for his workforce and 'imported' factory operatives from all over Derbyshire, preferring weavers with large families who had plenty of children to work in the mill. Cromford Mill was only the first in Arkwright's large and profitable empire of factories, which spread from Derbyshire into Staffordshire, Lancashire and up into Scotland. Many of his mills took power from brand new developments in steam-engine technology. In fact, Arkwright's mills were so profitable that rival millowners sent in spies to discover the secret of his success.

A testament to Arkwright's sharp business acumen came on his death in 1792, when it was found that he was worth half a million pounds, a staggering amount of money in the 18th century.

by Nick Harling

1704-1780

Inventor of the Flying Shuttle

John Kay was born near the Lancashire town of Bury. Very little is known of his early life, but by 1730 he had already applied to patent a machine for cording and twisting worsted. However, it was a subsequent invention which really revolutionised the cotton weaving process and is now seen as one of the single most important inventions of the nascent industrial revolution.

Producing cloth on a simple handloom was a slow and labour-intensive process. Passing the shuttle containing the weft through the 'shed' formed by lifting alternate warp threads was an awkward business - it effectively limited the width of cloth that could be woven to the length of the weaver's arm as he passed the shuttle through.

Kay's great innovation was to increase the speed at which the shuttle passed across the loom, and to increase the distance that it travelled. He installed two 'shuttle boxes' at either side of the loom, connected by a wooden track or 'shuttle race'. The shuttle was propelled backwards and forwards along the race by means of a 'picking peg' which the weaver jerked from side to side. The speed at which a piece of cloth could be woven increased dramatically.

Kay's 'Flying Shuttle' was the first true mechanization of the textile weaving process. The success of Kay's invention greatly increased the demand for spun cotton, as weavers could now produce finished cloth far more quickly than they could be supplied with the spun thread. The knock-on effect of this shortfall was for other inventors such as James Hargreaves and Samuel Crompton to mechanize the spinning process later in the 18th century.

Sadly, as with many other innovative men, Kay was not recognised as a prophet in his own land. Greedy manufacturers refused to pay him royalties for his invention and machine-breakers raided his Bury home in 1753. He left England for France shortly afterwards and is thought to have died in poverty.

His son Robert continued the Kay family tradition by inventing the 'drop-box' in 1769, allowing rapid interchange of multiple shuttles with different coloured threads on one loom.

By Nick Harling

Roger Haydock was an ancestor of mine. He was referred to as "Uncle Roger" and this picture of him hung in my Aunts' house for many years.I often wonderd how we were related. I have now discovered that he was my Great, Great, Great,Great Uncle, with Roger's sister Ellen being my direct ancestor. She was the Grandmother of John Aspden Ormerod, JP and Mayor of Blackburn.He was my Great Grandfather.

A book was written about him in 1912 , by the Rev. John Whittle."Owd Roger":Bible Colporteur and Primitive Methodist Lay Preacher. The story of a Bible-Inspired Life.

"Owd Roger", as he was affectionately known, was born on 26th December 1809, or as he used to say " I am three days owder than Mester Gladstone".

Several other luminaries were born in this year - Tennyson, Darwin and Mendelssohn .

The Battle of Waterloo was won when he was only five years old, but he could remember the scenes of jubilation at Wellington's victory.

His father was George Haydock, a farmer and handloom weaver in Clayton-Le-Dale.Roger was the fourth of a family of twelve children. His father was well known in the district. He was singing master at Salesbury Church for 46 years.

He began work at an early age. At four he was a bobbin-winder. By seven he was acting as a minder to a handloom weaver and soon after took charge of the handloom himself. He carried his finished pieces to the "Putter-out" in Blackburn. First to James Fisher of Ainsworth Street and then to James Briggs of New Water Street.When work was available he earned from 8s to 12s a week.

He said" Things in those days were very dear; we were hampered on all sides; poor pay and expensive food. Tea was only a luxury for grown ups, children were never allowed to partake of it. The youngster's drink consisted of cloves, pennyroyal and such like.. Flesh meat was a luxury to be dreamed of, but very rarely to be tasted. We had "hasty puddings" three times a day, and for our Sunday dinner, potatoes and bacon collops. A family that could boast of a red herring meal was considered as belonging to the higher classes."

Roger lived through turbulent times in his youth. In his early days wheat stood at famine prices and salt was taxed at thirty times its ordinary value.Thus he became a keen supporter of Free Trade and the abolition of the Corn Laws. He remembered the loom breaking riots of 1826 and the attack on the Dandy Factory in Blackburn.

The nearest town with an MP was Preston, with the Preston Guardian the only paper circulating in his area of Lancashire. As the cost of the paper was generally beyond the reach of the ordinary people, it was arranged that a different family would purchase it each week and make it available for all. At least this gave them an insight into the Parliamentary news of the day.

The Preston Guardian presented a supplement to one of its issues containing a portrait of the great Chartist Fergus O'Connor. This was considered such a prize that the villagers threw dice to see who would carry off this great treasure. Roger was the lucky winner and returned home in high spirits.

At twenty four Roger married Mary Howarth of Wilpshire at Blackburn Parish Church .The marriage produced nine children."Eawr Mary"(as Roger referred to her) had to teach her husband to read, as one of her first wifely duties.Soon after the marriage, Roger gave up weaving and changed his trade to quarryman, working at William Forrest's delph at Lower Cunliffe. In those days it was expected that quarrymen would consume large amounts of alcohol, and Roger was no exception.Indeed he was very popular with publicans for he was a good singer and dancer.He was persuaded to attend a temperance meeting in the old Music Hall off Mincing Lane, where Dr. Skinner, of Mount Street Chapel spoke eloquently about the evils of drink. This made such an impression on Roger that he signed the pledge that night. This was in 1841 and he remained faithful to the temperance cause for sixty three years.

He was to travel hundreds of miles, spreading the message of teetotalism.

He acted on impulse again when asked to become a seller of bibles known as a "bible colporteur". He was persuaded to give up his quarrying by John Baynes, local secretary to the British and Foreign Bible Society and Mayor of Blackburn in 1858-9.He promised him that he would earn £1 a week, whether he sold any bibles or not. Roger considered this to be a good amount of money, but was concerned that he wasn't suited to the task. However he agreed to take it on.

His fears were unfounded as he had great success and it was estimated that he sold more than 100,000 bibles and testaments to working people. He covered most of Lancashire and the West Riding of Yorkshire on foot, entering all the mills he passed on the way. For more than 20 years, he was to be found on Blackpool beach, during the summer season, where his wit and good humour made many converts.

Along with his Bible selling, Roger was a lay preacher for sixty one years on the Primitive Methodists' Blackburn First Circuit. The "Ranters" as they were known were very active in Blackburn. He preached in most of the villages and hamlets for many miles around Blackburn, as well as in the town itself.He and his wife were also Sunday School teachers, with Roger rising to the rank of Superintendent.

For many years, he spent his birthdays at Duxbury's Temperance Hotel on Railway Road, where he renewed old acquaintances.He attributed his longevity to "Temperance in all things, and the grace of God".

A stained glass window to his memory was erected in the Primitive Methodist Church, Montague Street. The inscription read "To call to remembrance the saintly character of Roger Haydock, Christian worker, Temperance reformer and worthy citizen, who entered into the reward of the pure and faithful, March 22nd 1904, aged 95. Blackburn had lost one of its most famous characters, who had outlived his contemporaries, his wife and even his own children. Only one daughter Ellen Walmsley,with whom he lived,remained.

His funeral, which was held at Montague Street Primitive Methodist Church was attended by family and a large contingent of religious, temperance and civic figures.

James Taylor Thom Ramsay was born in Dundee on July 14th 1854. His father George was employed by the Harbour Trustees. His mother Margaret was the daughter of James Thom of Peterhead. At the age of ten he joined the spinning department at Baxter Brothers and progressed via the weaving department to the mechanics' shop, where he completed his apprenticeship in 1872.

He worked from five in the morning until six at night and supplemented a meagre income by acting as knocker-up. He devoted what spare time he had to study: Latin grammar and Euclid, and obtained a post as teacher to the blind. Again the pay was meagre and he worked as a proof-reader on the Dundee Advertiser to make a living wage. By now he was working eighteen hours a day.

In 1874 James had obtained a scholarship at the Dundee High School. In 1879 he matriculated at Edinburgh University, where the strain of over-work at last became too much and he suffered a breakdown. He cured himself by taking a passage on a steamer bound for Newfoundland. On his return he worked first as assistant to a doctor in Wharfdale and then joined Dr Grime, the senior physician, in Blackburn.

James returned to Blackburn after completing his studies at Edinburgh in 1891 and married Margaret Baines. He became a familiar figure in the town with his frock coat and broad-brimmed, silk hat. He succeeded Dr Grime as the Factory Doctor and was known to stand no nonsense.

James was first elected to the town council in 1896 as Conservative representative for St Mark's Ward. He became an alderman in 1908 and was Mayor for the years 1922 - 24. On 30th May 1923 he opened Roe Lee Park and is pictured above at the ceremony and left at the game of bowls afterwards. He retired from the Council in 1930. He served as a magistrate for 32 years, presiding over the Tuesday court and meting out justice tempered with mercy. He was a keen reader, being President of the Dickens Fellowship. His paper on Burns, which he read at the poet's centenary, was widely admired.

Dr J T T Ramsay died at the Royal Infirmary on the evening of Monday May 10th 1937 at the age of 82. Typically only the day before he'd been at work, visiting patients. After a funeral service at St John's his remains were cremated at Manchester Crematorium. The flowers were laid in the Garden of Remembrance at Corporation Park, where family, friends and former patients could view them.

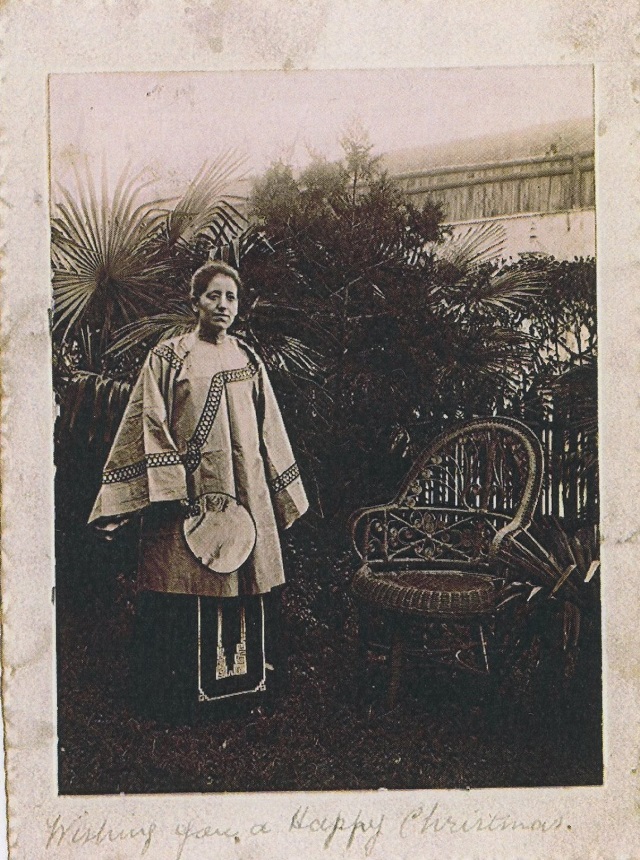

David Johnson, a photography pioneer, was born and baptised in Blackburn in 1827. He was the son of William a grocer and corn miller and Hannah. His father, Willam was born in Prescott in 1794 and Hannah, his mother, in Kildwick, Yorkshire in 1784. The family lived on Northgate and David joined his father in the business. Census returns from 1851 have William listed as a corn dealer and cheese factor and David as a corn dealer and shop keeper.

By 1861, Hannah has died, William is still a corn dealer, and David is a photographer. In 1859 he built premises on the corner of Cardwell Place and Corporation Street, close to the scene of his famous photograph of the Peel homestead. He leased the ground floor to The Blackburn Times and he used the top floor as his studio.

We know that he exhibited 6 examples of his work at a photographic exhibition in Amsterdam in 1855.

After the 1861 Census the Johnson's no longer appear on the Blackburn Census. We do know that David had sold the business sometime in the 1860's as the company had become Blackburn Photographic and Fine Arts Company Limited (late David Johnson) of 3, Corporation Street.

David married Jemima Jones in Wrexham in 1863. In 1865, their 5 month old daughter Margaret Hannah died and was buried in Blackburn Cemetery. At this time they were living on Wellington Street St. John's.

In 1871 David and Jemima are listed on the Census in Wrexham. They have a 1 year old son, William. David's father, William, is also living there. He is a retired corn dealer and David is a corn miller.

William senior died in 1872, but came back to Blackburn for burial alongside his wife and grand-daughter.

10 years later on the next Census, Jemima is living in Chester with 2 daughters, Edith Margaret 9 and Elsie Evadne, 5. There is no sign of David or their son William. She has several boarders and 2 servants residing with her.

So what has happened to David? On the 1881 Census the only David Johnson of the right age and birthplace of Blackburn is in London in a private hotel. He is listed as having no occupation. William the son has disappeared by 1881 so it is likely that he died in infancy. In 1891 David, Jemima and their 2 daughters Edith and Elsie are living in Croydon, where he is described as a retired manufacturing chemist. By 1901 David is widowed and living with Elsie in Wandsworth. It looks like he died the same year, in Wandsworth.

According to the following account of David Johnson's life, by George Miller, he moved to the Metropolis and made his fortune from a drink "Zoedone". However in Flaubert's novel "Madame Bovary" there is a reference "Come round to Bridoux's now and have a glass of zoedone." As this was published in 1857, when Johnson was pioneering his photographic techniques in Blackburn, could he really have been the inventor?

Some new information has been supplied to us by Wrexham Local Studies Librarian.There was a Zoedone works manufacturing mineral water drinks in Pentrefelin, Wrexham, with a London head office. The firm was established in 1880. It was the quality of the water which made Wrexham a popular place for brewing and drinks manufacture. So perhaps David Johnson was the owner?

From Blackburn Worthies of Yesterday, 1959-

Local devotees of the photographic art are perhaps unaware that more than one disciple of W.H. Fox Talbot or David Octavius Hill flourished in Victorian Blackburn, and even achieved considerable fame outside its borders. I have in my possession a reproduction of David Johnson’s ambrotype photograph of the Peel homestead in Fish Lane, dated 1854, a fine, piece of craftsmanship from the hand of a master, and it is satisfactory to know that among the masterpieces of Victorian photography listed by the Arts Council in 1951 is a portrait entitled “A gentleman with a top hat”, by David Johnson, Blackburn, 1853.

It would be interesting to learn the identity of this top-hatted townsman of ours, or to know if this, or any other specimen of Johnson’s work survives.

David Johnson was an interesting soul, whose father was a grocer in Northgate, in which thoroughfare he too set up in business, down a narrow entry opposite Lower Cockroft. The premises are still tenanted by a picture-framer I believe. After the old property in Fish Lane had been demolished, he built the premises at the corner of Corporation Street and Cardwell Place. He used the upper rooms for his studio, leasing the ground floor to the proprietors of “The Blackburn Times” newspaper. Whilst residing in the Snig Brook area, he found that the Gawthorpe water then supplied to its inhabitants was injurious to health, being of a gravelly nature. This he promptly countered by patenting a filter, which he retailed to the neighbours at cost price.

Ultimately Johnson deserted Blackburn for the Metropolis, where he is reputed to have made a snug fortune out of a patent drink called “Zoedone”. A melancholy accident happened at his father’s death, when the coffin holding his remains was damaged in a railway accident at Clifton Junction near Bolton, when on its way to Blackburn for interment.

Two articles from the Blackburn Standard provide an insight into David's photographic skills.

LIFE-SIZE PHOTOGRAPHIC PORTRAITS

We had the opportunity the other day of seeing in the studio of Mr. David Johnson, a beautiful life-size portrait of the late John Addison, Esq. The portrait was taken only a few weeks before the death of the lamented judge, and on the day he was taken ill in Blackburn he had arranged to call at Mr. Johnson’s for the purpose of seeing it. It is only a striking likeness, but being life-size, it is more life-like than any miniature can possibly be. The apparatus which Mr. Johnson has fitted up for the purpose of taking life-size portraits – of which the portrait of Mr. Addison is the first fruits – is very perfect, and has necessarily cost a great deal of money. Perfect as it is, however, Mr. Johnson hopes to improve it, and to so simplify it that he will be able to produce life-size portraits at a comparatively trifling cost. Looking at the great advance which such a speaking life-size portrait as that of the late John Addison, Esq., is on the dim miniatures which photography first produced, and that only a few years ago it is difficult, and would be hazardous, to set any limit to either the perfection or economy with which the ‘human face divine’ may in a few years be made almost to breathe from the canvas, if we may so speak, of the photographer.

From Blackburn Standard 17th August, 1859

LECTURE ON PHOTOGRAPHY, WITH ILLUSTRATIONS.

On Thursday evening, a lecture on photography, illustrated by experiments, and concluding with the exhibition of a series of photographic dissolving views, by Mr. David Johnson, photographic artist, was delivered in the ‘Oddfellows’ Hall, Heaton Street, to a large and delighted audience. The room was crowded to the door. The lecturer, in a simple and intelligible manner, sketched the history of photography from the time of the alchemists, who knew, but paid no attention to the fact, that the salts of silver were decomposed by light. The fact remained simply a fact for centuries, till Wedgewood and Davy, in the course of their experiments, undertaken for the purpose of producing pictures by the agency of light, discovered, after several years experimenting, the secret of fixing the image produced by light, and making it permanent. That was a great step in advance, but it was left for Talbot and Daguerre to discover the complete process of producing photographs and fixing them. This they did in 1839, and it is a curious fact that the announcement of the discoveries they had each made, as the result of experiments carried on independently of each other, and without either of them knowing the nature of the other’s researches, took place in the same month of that year. Talbot’s discovery was the process of producing photographs on paper; the discovery of Daguerre was that which was afterwards and still is known by the name of Daguerreotype, a photograph on silver. The discoveries of these illustrious names were further improved upon by men of science, and the latest and most wonderful discovery in the art is that which was made by Mr. Scott Archer, of London, known as the collodion process. At this stage of the lecture Mr. Johnson illustrated the collodion process, by going through it and producing before the audience a picture of Clitheroe Castle. He then stated that Mr. Mercer, of Oakenshaw, had introduced a new process, which was still a secret, for producing blue photographs from a negative; and this blue could afterwards be changed to any other colour. An experiment illustrating the first part of Mr. Mercer’s discovery, which has been imparted to Mr. Johnson, was then performed, and a portrait of the Rev. Mr. Macfie, in blue was produced. This discovery, Mr. Johnson remarked, was a most important one, as the chemicals used by Mr. Mercer were simple and inexpensive, while the chemicals which were now used in photography were very expensive, being mostly gold and silver. One firm in London, he stated, has last year dissolved two tons of silver for photographic purposes. At the close of the lecture Mr. Johnson exhibited to the meeting a series of 29 photographic dissolving views, of cathedrals, castles, etc, closing up with some splendid views of sculpture. The views in themselves were only about two inches square, but they were exhibited on a screen 18 feet square, being magnified about 15,000 times. The light by which they were exhibited was the oxycalcium light, and the effect was astonishing and most gratifying. In the course of the exhibition of the dissolving views, Mr. Rhodes played some choice pieces on the harmonium. At the close of the proceedings Mr. Johnson was cordially thanked for his lecture and exhibition.

From Blackburn Standard 18th January, 1860

We are fortunate to have some examples of his work, particularly the photograph of Robert Peel's birthplace on Fish Lane(shown above) from 1854 and the newly built Town Hall from 1856. Some examples of his portraiture are on the previous page.