From the Blackburn Weekly Telegraph of 13th April 1912.

THE BLACKBURN EASTER FAIR.

There does not seem to have been about Blackburn’s Easter Fair this year the incessant gaiety and glitter which have characterised it on former occasions. Much that gave to it a spectacular interest has been missing. The booths with their refulgent entrances, within which bedizened women danced gaily, and men in unconventional attire invited you in raucous voice, to see the “greatest show in the world,” and the gorgeous picture “palaces,” were conspicuous by their absence, and the central walk of the fair was not so alluring or entertaining as formerly. The only show making any attempt at former garishness and ostentation was the menagerie, with its drum beating loudly, and its promise of a “man-and-lion” fight. This decline, noticeable year after year, caused one to speculate whether this ancient kind of carnival is at last on the wane. Many have thought it an anachronism, but still it has survived. “It’s a thing of the past, so far as towns are concerned,” said an old fair hand. “It offers no variety now like it used to, and every town of any size provides as much amusement every week as people require.”

There is still, however, much on a Fair which makes an irresistible appeal to those of boisterous temperament and exuberant sprits, and this week’s festival yielded merriment to all sorts and conditions of people, including the urchin, the town councillor, and the member of the cloth, and when weather permitted the Market-place was a scene of revelry. Shying is still popular, and jocose groups might have been found round the cocoanuts, the “Aunt Sallies,” and the “Dandies.” “Let’s have a go at the cocoanuts!” Observed one, and the balls were immediately flying from one hand and then the other. But the triumvirate in the centre, so temptingly arranged as to make believe they will almost topple over of themselves, were not so easily disturbed. The stallholder encouragingly assured you it was as easy to knock them over as it was to find your way home, but after a shy or two you became sceptical. You were either just too wide or two high; you might even rattle the cups, but still you would not achieve your object. But these repeated misses only added to the hilarity of the proceedings. “Don’t be beaten!” “Have another go!” Chaffingly added the onlookers as they noted your determination, and you proceeded until you sent one of the haired spheres topsy-turvy. You were afterwards surprised at your profligacy, and your friends provokingly told you had paid for the cocoanut. It was the same with the “Dandies,” in evening attire, and as they circled round they eluded you every time you tried to knock of their high hats. Even when hit, the “Aunt Sallies” sometimes resented to go over. “Hit them on the top sir!" said the man in charge, with the air of one telling you a secret. The “sally” on which was written “I wonder why you miss me sometimes” looked at you with taunting persistence, and you were not satisfied until you had had your revenge by bowling it over. There was, too, a certain fascination about the numerous games and competitions. Repeatedly the “Hoopla” was circled by people looking interestingly on while some one strained every nerve to “ring” a packet of chocolates, cigarettes or even a watch. Others watched folk endeavouring to throw “washers” in squares, the reward for which was a canary, which chirped cheerily as it noticed its would be possessor failing in his object. In these games, as in life, there are few successes and many disappointments, but at the Fair you laugh at your misfortunes and are happy, while the same philosophy is not shown in regard to life. The roundabouts and swings provided rollicking sport. To those whose nerves were steady and strong, who had a sort of reckless disposition there was an exhilaration in flying in the air, and, as they attained giddy heights, these shouted gleefully to those below, who stood amazed and fearful. To others, however, it was a different matter. Enticed by friends to have “just a try,” they soon began to quail. The colour gradually disappeared from their cheeks, there was a look of nervousness in their eyes, and as they realised haw far they were from terra firma, they clutched grimly to the boat, and the stoppage came as a great relief. They stood dazed for a few moments, and then, as they gradually recovered their composure, it was with them as with the raven, a case of “Never More!” People tumbled and tossed on the Joy Wheel, and their gyrations caused both themselves and spectators to laugh uproariously, while the Cake Walk jogged a few people along, though a little less violently, it appeared than hitherto. The motor cars and scenic railway seemed to capture popular fancy most and to administer more than anything else to the craving for sensationalism which many people who go to fairs possess. Being whirled round with bewildering rapidity, being run down a decline at exhilarating speed, was delirium to many, and in their intoxication they shrieked and screamed for joy. Many a Gradgrind might have reproachfully asked what in “the name of wonder, idleness, and folly” they were doing this for; but, then, the Fair is no place for the matter-of-fact man. The more gentle and graceful evolutions of the horses formed entertainment for others and particularly those anxious to display their equestrian grace. At the shooting galleries many a man had his reputed skill with the gun put to the test, while lusty youth found diversion in the mallet. There were present the inevitable character readers, with cap and gown to proclaim their learning. These men are wise in their day and generation, for they invariably inform their clients of only those characteristics which are pleasing, for they know that flattery never comes amiss. After profound and penetrating looks, they pronounce something after the following manner:

Excellent for business.

Sincere in friendship.

True loving nature.

Fond of home life.

Thoughtful for others.

A lover of order and neatness.

Tender hearted, &c., &c.

Suggest to the client that “There is nothing in it,” and they will blandly reply that “it’s a bit o’ fun.” The shows were largely concerned with the freakish, and one might also have seen a collection of snakes, or had one’s senses horrified by representations, in wooden models, of all the awful and ghastly means of torture used in all ages and all countries.

According to some accounts, the money spent at the Fair has not equalled the average.

“We have done badly, and some have barely cleared their expenses,” remarked the aforementioned fair hand. “The weather has been against us, it is true, but it seems to be the rule that we do not get the patronage we did. People can now go to the seaside for what they used to spend at the Fair in a day, and if I were like them I would do the same and get some pure air. When the weather is like what we have been having, folk go to places of amusement, where it is more cosy and comfortable, and the result of it is, many of the people who come to the Fair have little or no money to spend. They visit us just to look. Look there,” he added, as he pointed to a long line of people who were gazing languidly on, while the shows and roundabouts were almost empty.

FAIR-GROUND ACCIDENTS.

Isabella Duckworth, weaver, of 66 Holly-street, Blackburn, was on the “cake-walk” on the Fairground on Monday, when, through a portion of the woodwork giving way, she received two bruises on the right knee.

Four young women were riding on one “bird” on a roundabout on Monday, when a brass rail was pushed from its fastening, and three of them fell into the street. Agnes Ainsworth, weaver, 24, Walnut-street, sustained a cut on the head, and Sarah Holmes, weaver, of 2, Sour Milk Hall-lane, on being taken home on the horse ambulance was found to suffering from slight concussion. Two other females escaped injury.

Frank Woods, basket maker, 37, Adelaide-street, was struck on the head by a wooden pole, which, dislodged by the high wind from the scenic railway, fell a distance of about 20 feet. The injury was dressed at the central Police Station, and after resting a little while, Woods was able to walk home.

From the Blackburn Weekly Telegraph of 20th April 1912.

THE ECLIPSE AS SEEN AT BLACKBURN.

The quartets of photographs, taken by “Telegraph” cameris’s at the times named in the corners, shows the progress of the eclipse from the beginning to the time of greatest obscuration at 12.10 p.m. on Wednesday noon. In common with the rest of the country, and all places where the eclipse was visible, Blackburn took great interest in the phenomenon. Dotted all over the town, on the outskirts, and in the surrounding villages, were groups of interested observers; and as there was for the most part a clear sky, all that was needed was a piece of smoked glass to make perfect observation possible. In the schools the occasion was taken advantage of to instruct the children in regard to the eclipse, and not merely to interest them in a spectacle. The Girls Department of Moss-street Council School may be taken as typical. Here, under the direction of Miss Geddes, the headmistress, the children, pressing into service bits of smoked glass made some very practical observations. There was a blackboard out of doors, and they sketched as they saw. In the afternoon the children of Standards III and IV, the nine and ten year olds, either drew and coloured, or drew, cut and mounted illustrations of their own. Some of the results were most excellent. The mysteries of the solar eclipse were unfolded to them, and they are likely to remain with them a living memory for the rest of their lives.

From the Blackburn Weekly Telegraph of 20th April 1912.

THE SINKING OF THE TITANIC.

All the world has been horror stricken this week, by the awful doom that has descended on the White Star liner Titanic, the greatest ship that as ever been despatched to sea. Only a little over a week ago, on Wednesday, the 10th inst., the Titanic, a monster of 46,000 tons, with eleven decks, palatial appointments, and accommodation for close on 5,000 souls counting both passengers and crew, sailed proudly down Southampton Water upon her maiden voyage to New York. Today she lies two miles deep on the bed of the North Atlantic, a smashed and splintered wreck, and out of the 2,358 men, women, and children she carried no fewer than 1,600 are dead.

It was in the last hour of Sunday that the appalling calamity happened. The great ship had entered the most dangerous stretch of ocean lying between England and North America, a point well to the south of the Grand Banks of Newfoundland—dangerous because of its fogs and wandering icebergs; but the night was clear, the storm winds were at rest, and all peril seemed far removed, when suddenly, at half-past eleven an iceberg loomed ahead, the helm was put hard over and the Titanic sheered swiftly off her course. But it was two late: her bow sped clear, but the hidden fangs of the berg caught her massive hull amidships and crushed in her stout plates just as though they where of egg shell thickness. Immediately a wireless call for help was flashed into the hidden spaces of the sea. It was picked up by the Virginia of the Allen Line, by the Baltic, by the Olympic, the Titanic’s own sister ship and by the Carpathia, one of the smaller of the Cunard boats, and at once a madly thrilling race to the scene of the disaster was begun, but the ships were all to far away, and the giant was too sorely wounded, and when the first of the liners, the Carpathia, reached the scene, nothing remained but a mass of wreckage and a flotilla of boats with fewer than 800 people. One by one the other ships came up and made vigorous search, but it was all in vain, and one by one they departed on their appointed ways, leaving the Carpathia to convey the survivors to New York.

The scenes in the dock at New York as the survivors landed were full of suppressed excitement. Men were in hysterics, women fainting, and children almost crushed in the arms of those welcoming them. The number of badly injured was not nearly so large as had been imagined. Cases requiring hospital attention were few, but the strain of the trial of their lives had left unmistakable signs in the faces of the arrivals.

When most of the passengers had departed, crowds remained about to get a glimpse of the rescuing steamer, and to hear the harrowing stories which had been brought back by the ship. Among the most affecting scenes at landing was the sight of the women steerage survivors as they came down from the deck, thinly clad and shivering, their eyes red with constant weeping. In their faces was the drawn look of desperate fear. They were taken care of at once by members of the numerous charitable organisations who were at hand.

It was learned from survivors that five (some say six) of the rescued died on board the Carpathia, and were buried at sea. Three of these were sailors. The other two or three were passengers. Exposure to the ice and the cold sea where the Titanic had foundered had brought about their deaths.

SHIP SHATTERED BY EXPLOSIONS.

Mr. Hugh Woolner, of London, one of the survivors, said that after the collision he saw what seemed to be a continent of ice.

“It was not thought at first,” He said, “that the liner had been dealt a dangerous blow. Some of the men were in the gymnasium taking exercise, and for some minutes they remained there not knowing what was going on above their heads. After a while there was an explosion; then a moment later a second explosion. It was the second which did the most damage. It blew away the funnels and tore a big hole in the steamer’s side. The ship rocked like a rowing boat, and then careened over on one side to such an extent that the passengers making for the boats slid into the water. The ship filled rapidly, and as it was evident that she would go down I jumped into the boat as it swung down the side.”

The shock of the collision with the iceberg was scarcely noticeable. Many people seem to have slept through it. Emile Portaluppi of Italy, a second class passenger, said that he was first awakened by the explosion of one of the ships boilers. He hurried up to the deck and strapped on a lifebelt. Following the example of others, he then leapt into the sea and held on to an ice floe, with the help of which he managed to keep afloat until rescued by a lifeboat.

The crash against the iceberg, which was sighted only a quarter of a mile away, came almost simultaneously with the click of the levers, operated from the bridge, which stopped the engines and closed the bulkheads. Captain Smith was on the bridge at the moment. Later he summoned all on board to put on life preservers, and ordered the boats to be lowered. The first boat had more males as they were the first to reach the deck but when the rush of women and children began the “women first” rule was strictly observed.

According to the story published by the “Evening World,” revolver shots were heard just before the Titanic went down. Many rumours were in circulation in consequence, one being to the effect that Captain Smith had shot himself, and that the first officer, Mr Murdoch, had ended his life; but Captain Smith was last seen on the bridge just before the ship sank, leaping into the sea only after the decks were awash.

The great liner went down with the band playing taking to death all but 775 of its human cargo of 3,340.

Respecting the scene on board the Titanic when the liner struck, accounts disagree widely. Some maintain that comparative calm prevailed. Others say that wild disorder broke out, and that there was a maniacal struggle for the boats. According to sensational stories, told by hysterical persons who would not give their names, Captain Smith killed himself on the bridge the chief engineer took his own life, and three Italians were shot in the struggle for the boats. These stories could not be confirmed in the early confusion attendant the landing of survivors.

It was asserted that the ship was going at the rate of 23 knots an hour when she struck the iceberg.

Colonel Gracie, one of the survivors, denies with emphasis that any men were fired upon. He declares that only once was a revolver discharged, and then it was for the purpose of intimidating some steerage passengers.

The most distressing stories are those given by the passengers in the lifeboats. These tell not only of their own suffering. They give harrowing details of how they saw the great hulk break in two and sink amid explosions. It sank stern first, and groups of survivors plainly saw many of those whom they had just left behind leaping from the decks into the water.

The “New York Herald” published a story of the disaster from a correspondent who was on board the Carpathia. He speaks of the great courage of Titanic’s crew, which however, could not exceed that of Mr. Astor, Mr. Harris, Mr. Futrella and others. The cabin passengers, many of those with life-preservers on, were seen to go down in spite of their preservers. Dead bodies floated to the surface as the last boats moved away. The ship’s band, which gathered in the saloon near the end, played “Nearer, My God, to thee.”

As soon as it was seen that there was real danger it was decided to place the women and children in the lifeboats. The boats went over the side at 12.15 a.m., but even then those remaining on board did not realise the urgency of the situation, and presumed that the measure was precautionary. At 2.20 the Titanic suddenly rose and made a plunge downward. One boat was smashed as soon as it was lowered. A score of persons jumped overboard. Some of those were pulled into boats after the disappearance of the Titanic. The survivors rowed about searching for the remainder of those who had jumped, and those who had embarked in collapsible boats were picked up in this way.

One of the Carpathia’s stewards said:

“Just as it was half daylight we came upon a boat with eighteen men in it, but no women. Between 8.15 and 8.30 we got the last two boats crowded to the gunwale, almost all the occupants of which were women. We then started to make straight for New York while the Californian remained to look for more boats. While we were pulling the boatloads the women were quiet enough, but when it seemed sure that we should not find any more persons alive, and then bedlam came. I hope never to go through it again. The way those women took on for folk they had lost was awful.

CLITHEROE MAN ON BOARD.

Clitheroe has a connection with the ill fated Titanic, Mr Harry Ashe, a brother in law of Mr. T. Rawsthorne, a local watch maker, being a steward on the vessel.

BLACKBURN CONDOLENCES.

At a meeting of the executive of the Blackburn Conservative association on Wednesday night, Mr. A. Nuttall J.P., presiding, a resolution was adopted on the motion of Councillor Ramsbottom, seconded by Mr T. Isherwood, expressing sincere and profound condolence with the bereaved relatives of those who lost their lives in the Titanic disaster, and also sympathy with the owners of the vessel.

A BLACKBURN VICTIM OF THE DISASTER.

“Jonathan Shepherd, thirty-one years of age, Bellevue-terrace, Southampton, native of Whitehaven, junior assistant engineer.” Such was the description published in the Seamen’s Registry Official list of the crew of the ill-fated Titanic of a well known Blackburnian, the son of Mr. J.B. Shepherd, of London-road, to whom the sympathy of all go out in his loss. The deceased, who held a first class chief engineer’s certificate, had been in the service of the White Star Company for between five and six years, which had been spent on the Adriatic and the Olympic, prior to his being promoted to the Titanic when she was launched. There is something most pathetic in the story of how Shepherd left home for what proved to be his last voyage. Whether it was the proverbial sailor’s superstition or some other reason it is impossible to say, but the fact remains that he was very dejected, and did not want to go. He could not account for the despondency, and he became more and more “down in the dumps” as the time for him to join the vessel approached. The whole affair is most remarkable, but more so were his last words at home. He appears to have been thoroughly upset, and going up to the photograph of his late mother, which hung upon the wall, he exclaimed in a broken voice: “Not long, mother, not long.” Then he rushed out to catch his train, unheeding the words of some of his relatives, who could not account for his strange behaviour, and who were trying to comfort him. “What are you afraid of?” asked his father, but he could not give any reply. “Are you afraid of Death?” he was asked, and answered, “No, I am not afraid of death; but I don’t want to go.” This statement of events is quite true, and time only showed how correct the young sailor was in his presentment. A tall, handsome man, over six feet in height, Mr. Shepherd, who was a bachelor, has not been much in Blackburn of late years. He served part of his time at the Canal Foundry, and completed his apprenticeship at Sheffield. Afterwards he spent about a year on a coasting steamer, subsequently sailing under the Castle Line flag in a 12,000 ton ship trading between China, Japan, and New York, and left with the highest credentials to join the White Star Line. He was one of the crew of the Olympic and when that liner was in collision with H.M. cruiser Hawke displayed great presence of mind, for on hearing the crash, he at once closed the water tight doors, although he was up to the knees in water at the time.

Mr Jonathan Shepherd was born on March 31, 1880 in Whitehaven, Cumberland. He moved to Blackburn with his family when very young and served an apprenticeship with James Davenport of that town. He worked for Messrs. Howard & Bullough of Accrington and Hadfields of Sheffield before commencing a seagoing career with W.S Kennaugh & Sons of Liverpool. Shepherd served on ships owned by James Chambers & Co. of Liverpool and joined the White Star line after obtaining his first class marine engineer's certificate of competency. He served on the Olympic before joining the Titanic. He was unmarried.

Shepherd was on duty on the evening of April 14th, 1912. After the collision he helped the other engineers rig pumps in boiler room No. 5 but broke his leg when he slipped into a raised access plate. Leading fireman Frederick Barrett and engineer Herbert Harvey helped him to the pump-room. Shortly afterwards the nearby bulkheads was breached and Shepherd was left helpless as the waters rose around him.

BLACKBURN ROVERS RESULTS FOR MARCH 1912

April 6 Manchester City H. W. 2-0 Clennell, Chapman. Gate 18,233

April 8 Sheffield W. A. D. 1-1 Clennell. Gate 15,000

April 13 Everton A. W. 3-1 Clennell 2, Latheron. Gate 40,000

April 15 Oldham A. H. W. 1-0 Latheron. Gate 7,159

April 22 W. Arsenal A. L. 1-5 Ducat o.g. Gate 7,000

April25 West Brom H. W. 4-1 Aitkenhead 2, Clennell 2 Gate 10,601

April 27 Newcastle U. H. D. 1-1 Latheron. Gate 10,000

April 29 Manchester U. A. L. 1-3 Clennell. Gate 20,000

April 3 F.A. Cup Semi Final reply West Brom * L. 0-1 Gate 20,050

*Played at Hillsborough, Sheffield

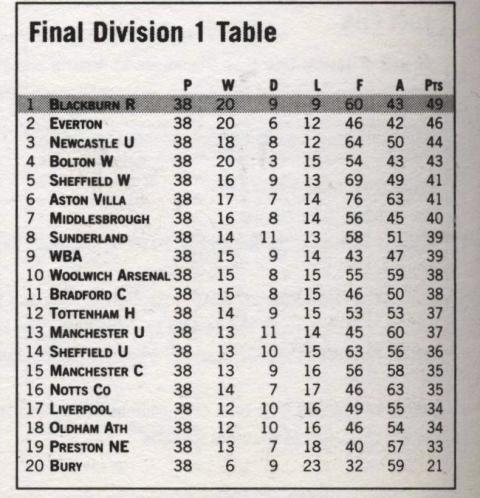

ROVERS AS LEAGUE CHAMPIONS.

The Football season of 1911-12 will be long remembered in Blackburn by all who take an interest in the sport. Recent campaigns have borne testimony to the steady rise of the Rovers and now they stand forth as the champions. The honoured achievement is thus gained for the first time in the history of the club, and on all hands it is admitted the Rovers are worthy of the honour, for they have played consistent football for the greater part of the season. Without wishing to detract from the deeds of the players in the past, it may be said that the season just closed has been the greatest in the history of the Rovers. They have, for instance, gained more wins than ever before, and for the first time since 1894-95 when only 30 matches were played, have kept their losses down to single figures. At Ewood Park they have not sustained a single reverse, thus equalling the feats of 1888-89 and 1909-10. In no year have more points been earned at home and only once have more been gained in away matches: whilst the aggregate number of points reaches 49, which easily surpasses their previous best—45—two winters back