The old clock on platform 13 at Manchester Piccadilly

Jeff Stone of the Exchange Arcade in

Fleming Square tried to buy the clocks in 2002 to save them for Blackburn but

wasn’t given the opportunity to quote a price.

He said; “we wanted to put them in Fleming Square to keep them in

Blackburn”. Currently one of the clocks is situated on Platform 13 (unlucky for

Blackburn) but there is no sign of the other one (it is rumoured that it was sold for £3,000 to a private collector

in America) the plot thickens.

Story Quotes and picture from

Lancashire Telegraph 20/6/2002 and 7/4/2003.

Researched updated

and written by Jeffrey Booth (Library Volunteer).

back to top

In the 1840's business men were beginning to realise that railways were the key to future expansion of the textile industry; before the railways, the only way to get their products to places like Manchester was by horse and cart, and, at 10d a mile and 10d per ton this form of transport was very expensive. A number of influential businessmen gathered at the Greenway Arms in Darwen one Friday afternoon in 1844 to discuss the building of a railway from Blackburn to Bolton, via Lower and Over Darwen.

The cost would be £213,600; the public were invited to buy shares at £25 each and 382 people applied but the bulk of the money was put up by four men, Henry Hornby, Charles Potter, Eccles Shorrock and James Kay of Turton Tower. All four bound themselves for £50,000.

copyright

Jeffrey Booth

Blue

Plaque Commemorating first sod cut by W.H. Hornby

On the Blackburn Bolton Line

On a blustery, wet, September 27th 1845, in a field close to where Darwen Station now stands William Hornby, using a new spade, cut the first sod. A blue plaque is situated at Darwen Station to commemorate this. The work of building the line began steadily, until it reached Hey Fold Farm; here, the farmer, Robert Smalley, attacked them with a well-worn spade. Work ceased for a while but eventually the lines were laid across his land. Altogether, 4,000 people were employed in various capacities on the line. They worked from dawn to dusk for a gold sovereign, drinking copious amounts of moonshine liquor brewed in illegal stills. The readily availability of ale caused problems, one worker, worse for wear from drink, attacked and killed a Blacksnape tailor. An additional story recalls that another worker left a candle on top of a gunpowder keg and forget about it; the next thing he knew he was flying through the air! Extra police had to be brought in at Turton because of the mayhem the workers were causing.

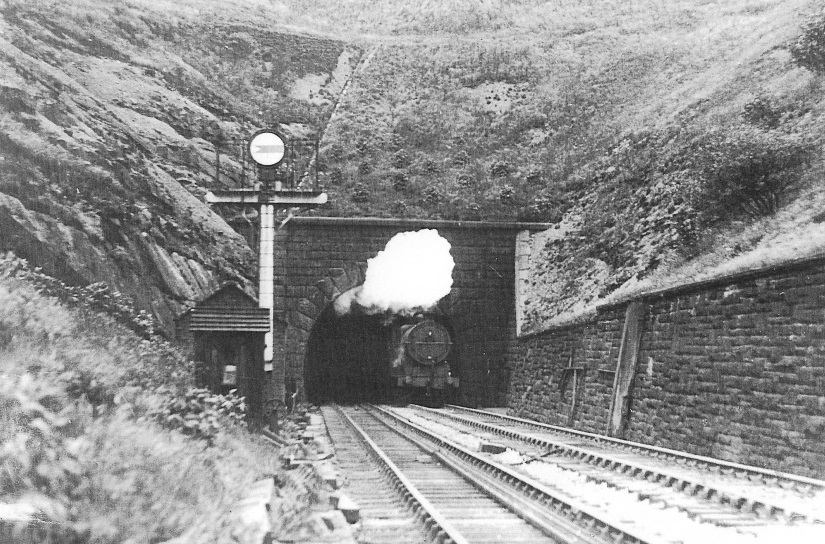

Creating a tunnel under the moors took two very difficult years. Wet workings, and roof falls claimed the lives of five men; it wasn’t called “the Black Hoyle (hole)” for nothing. Many of the men were recruited from the coalfields of Wigan and as far away as South Wales. Bricks for the tunnel arching were made from clay taken from William Shorrock's fields north of the tunnel entrance and baked in the contractors private kilns sited at the bottom of Pole Lane. Tunnelling through the Sough also caused problems for local enterprises.

Management at the Roxborough Calico Print works were not happy when their once clear hill water became muddy and they had to stop production; they won damages from the Railway to the tune of £5,000. Nearby, Brandwood pit was also troubled by flooding, and, for a time, a hastily improvised culvert diverted the flow. Thirteen vertical shafts were sunk to depths from 40 to 260 feet, one labourer slipped and fell down shaft number nine, and his body was never recovered. The second death was that of the youngest employee, 12 year old Billy Godbhere, whose job was running to the smithy with picks that workers sent up for re-sharpening. Between times he watched the hoppers as they resurfaced with soil for tipping. Bored by the monotony, he gave one swinging hopper a playful shove, striking it against a small lorry nearby, caught by the unexpected rebound, the hapless child was knocked over the brink of the 260ft chasm and his body was never recovered. Whilst the tunnel was being dug an engine driver, Thomas Heaviside, was killed when his locomotive exploded. Two other men died in a macabre incident, they were a father and son. The men were employed, after the opening of the railway, to seal up two shafts. There was a wooden stage which spread across the 10ft diameter openings at surface level. On the fateful day, unbeknown to them, an overnight storm had washed away a lot of loose earth from under the platform of shaft 5, when the men stepped innocently onto the delicately poised planking it tilted sharply downwards plunging them a hundred feet below to their deaths, an avalanche of rubble cascaded down after them entombing them forever.

The line was opened from Blackburn to Sough on 3rd of August 1847 and from Sough to Bolton on Monday 12th June 1848. On this day at 7am a regular service train made up of eight carriages packed to capacity left Blackburn, drawn by a Hawthorn 0-6-0. On the opening run to Bolton a band of musicians accompanied the intrepid passengers and the journey was completed, uneventfully, in thirty eight minutes; the journey by stagecoach would have taken nearly 3 hours.

Picture of Sough Tunnel courtesy of

Darwen Library

Another interesting aspect of the line was the use of an iron bridge to carry the railway over the canal at Hollinbank, Blackburn. The engineer in charge of the building of the railway, Charles Vignoles wrote in his diary that this was the first time ever that such a bridge as this design was erected anywhere. It became a common feature later of railway building all over the world. So, if you travel on this line remember the sacrifice of 5 people who enabled you to do so.

From "The Blackburn Darwen and Bolton Railway" by W.D.Tattersall

Researched and written by Jeffrey Booth (Library Volunteer)

back to top

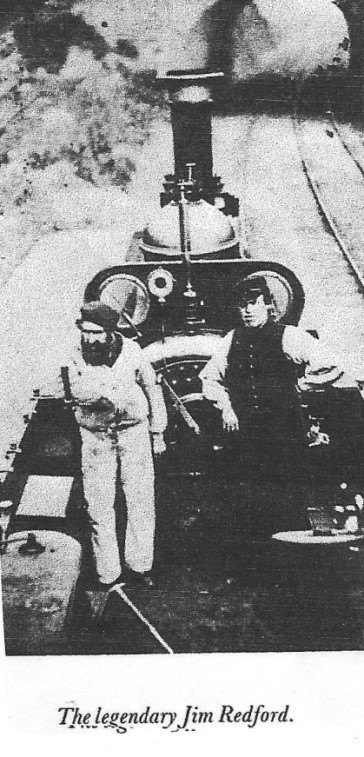

Blackburn’s first engine driver James Radford was born in Manchester in 1820; early in life he developed a taste for the study of practical science. For a boy from humble beginnings to turn his attention to studious pursuits in those far-off days required force of character and intellectual qualities much above average. Schools were hardly accessible and books even less so, yet by his own determination and exertions he not only became an excellent draughtsman and engineer, but later studied other subjects with equal success.

In 1840 he got work on the Manchester and Bolton Railway working on the line as a fitter on the permanent way, from that he went on to locomotive firing and driving. In 1843 the Manchester and Bolton Railway entered into an agreement with the Lancaster and Preston Railway to work their trains for so much a mile. The company sent Jim and two other drivers with three firemen to carry out the agreement. On the 1st of June 1846 (the day after he left the Manchester and Bolton Railway) he opened the Blackburn and Preston line, taking the entire charge of engines and men in addition to driving his own train. When the loop through Great Harwood and Padiham from Blackburn was opened in October 1877, Jim had the honour of driving the first train, continuing to work on this line until the sad accident at Blackburn in 1881.*

One famous story told by Jim and worth preserving was about a young gentleman who frequently travelled between Todmorden and Burnley, he made friends with Jim, who often let him mount the engine “Bucephalus” and drive it. He would accelerate the train and insist that the furnace door be thrown open in order that the currant of air might send the fire roaring and the sparks flying like some legendary magic horse. The amateur engine driver was the artist and poet Philip Gilbert Hammerton, who so enjoyed the experience that he wrote a poem of his experiences in his book “isle of Awe”. Despite allowing the above, Jim had the good fortune to be the means of saving life and he himself had a number of hairbreadth escapes. Jim was known as safe, and the feelings of genuine esteem and affection his passenger and friends had for their trusted pilot and guide was aptly set to poetry, yet again, by the Burnley poet Henry Nutter, whose composition Old Jim when published received an enthusiastic reception.

We boast of British heroes brave

Our valiant sons of Mars

Are proud to see our banners wave

Above our gallant tars

Our bonny barques that plough the main

We welcome with a cheer,

But seldom sing of a railway train Or a worthy engineer.

Then let my song your hearts inspire

To trust and honour him

That good old man we all admire

They call him “railway Jim”.

He bids the stoker mind the brake

Then with his whistle clear

He makes the sleepy pointsman quake

Old Jim the engineer.

When storms and tempests wildly rage

And lightnings rend the sky,

The lever doth his hands engage

Though thunders roll on high,

Midst danger signals green and red

In fogs or darkness drear,

There’s one with caution looks ahead

Tis Jim the engineer.

When special trains the line invade

Down Portsmouth lovely dale,

Or shunted goods the rails blockade

Or summer trips prevail,

With watchful eye he scans the road

When perils dire appear

He ne’er forgets his precious load,

Old Jim the engineer.

On pastures green the lowing herds

Lie fearless on the grass

Among the woods the little birds

Are chanting as we pass

Home’s sweet sequestered glades rejoice

The hills both far and near

Re-echo loud thy engines voice

Old Jim the engineer.

In winters cold or summer’s heat

I sit at ease with thee

MAZEPPA’S throbbing voice is sweet

‘Tis always dear to me

I’ve not the slightest dread, indeed

With thee I’ve to fear

Then welcome to thy puffing steed

Old Jim the engineer.

After the accident at Blackburn station Old Jim retired and spent the

next six years living in Burnley till his death in 1887.

THE FATAL RAILWAY ACCIDENT AT BLACKBURN. *

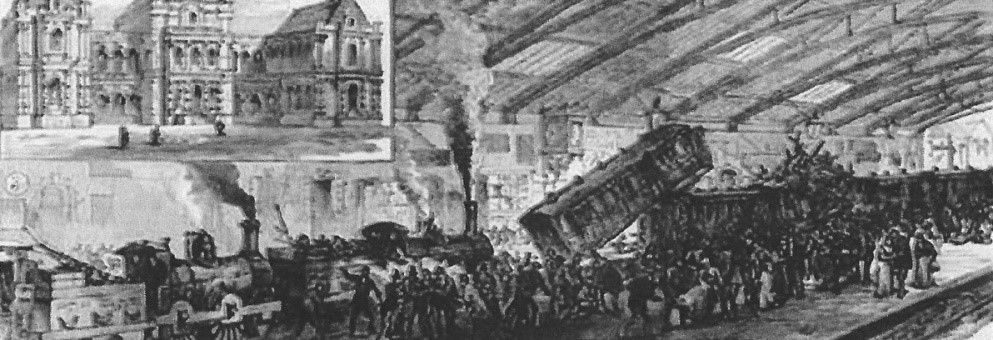

The Scene of the accident with Blackburn infirmary (inset) where casualties were treated.

(Picture from London Evening News)

A disastrous accident happened on Monday afternoon on August 8th 1881 at Blackburn station.

The train from Liverpool to Todmorden had arrived at 3 o-clock, the last carriage off that train was about to be shunted and attached to, “Vesuvius”, the Manchester to Scotland train, the Manchester train suddenly ran at some speed and collided with the shunting engine, both of which became interlocked and the carriages of the Liverpool train were telescoped into one another. Old Jim was the driver of the shunting engine, he jumped clear when he saw the train approaching but he was struck by a flying piece of buffer, sustaining a compound fracture of his right leg and was in the infirmary for two months. Unfortunately seven people died and twenty people were injured. As a result of this accident the station was deemed to be too small to handle the increase in traffic and was extended and remodelled between 1886 and 1888. One of the passengers who died was Charles C. L. Tiplady who was the second son of the Blackburn Diarist Charles Tiplady.

At the inquest into the accident the jury decided that the cause was the loose working of the signals and the excessive speed at which the train was being driven into the station, and that there ought to be more protection to the station than the present system of signalling. They did not attach any blame to any person and the verdict was “Accidental Death.

From “The Bolton, Blackburn, Clitheroe & West Yorkshire Railway” by W.D. Tattersall.

Pictures from the above and reports from London Evening News and The Blackburn Standard.

Researched and written by Jeffrey Booth (Library Volunteer.)

In 1863 a Railway Company calling itself the Lancashire Union Railway was formed due to the needs of Colliery owners in the Wigan area wanting to transport coal to the developing cotton mills of East Lancashire in the towns of Blackburn, Accrington and beyond. Back in 1860 the only route was a 21 mile journey via Euxton, Preston and on to Blackburn. A direct line was shorter just 7 and a half mile, building a line with a more

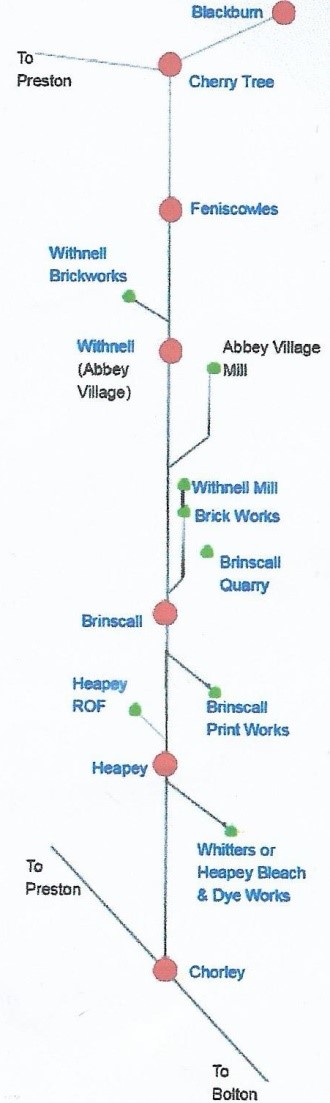

direct route would reduce coal prices for mill owners and households alike. It was thought that the line would reduce the price of coal by a shilling (5p) a ton, saving the mills of Blackburn £20,000 a year. The LUR had the strong support of another railway company-The London North Western. The LNWR saw a way into the strongholds of the Lancashire and Yorkshire Railway (LYR), if they helped the LUR. However, the LYR saw it as a threat to its East Lancashire stronghold and put forward plans for its own line. A long struggle followed whilst evidence by all interested parties was put before a House of Commons Committee. It was eventually decided that the LYR plan should be built jointly by the LYR and the LUR. On the 6th of December1866 work began, but it was delayed by further negotiations. Apart from the need to move coal the owners saw that there were several industries along the line that would want sidings running to them. Sidings were built for Withnell Brickworks, Withnell Mill, Abbey Village Cotton Mill, Brinscall Printworks, Heapey Bleach works and during the war a siding was built for the R.O.F. at Heapey. During the 60’s old Steam Engines were stored in the sidings waiting to be scrapped at Horwich Works. Although it was built mainly for goods transportation, between Cherry Tree and Chorley four stations were erected at Feniscowles, Brinscall, Withnell and Heapey at a cost of £ 10,000.The station at Withnell was closer to Abbey Village than its name implies.

All the stations were of the same design, except Brinscall which was a single storey building. The line opened for passengers on the 1st of December 1869. The railway cost over £ 500,000 to build which was very costly for such a short railway in Victorian Times, and it was well over budget due mainly to difficulties crossing the River Roddlesworth north of Abbey Village.

There was also a 9 arch viaduct at Botany Bay crossing the Leeds - Liverpool Canal and one three arch bridge (over the A.674 at Blackburn, which is still there today).

The Botany Bay viaduct was demolished on the 10th of November 1968 by means of explosive and watched by 2,000 onlookers, to make way for the M.61 Motorway.

The bridge at Feniscowles Station was demolished on 23rd/24th October 1975 but the bridge buttresses over the Leeds Liverpool canal are still there.

The line began just past Cherry Tree Station; there is still an old bridge just behind Livesey Hall.

The three arched bridge Over the A.6062 on Livesey Branch Road can clearly be seen.

Withnell old station seen from Road Bridge. The line carries on where the M65 is now, towards Withnell Station.

The Station is now a private house.

Heapey station is now a cattery and private residence.

The line between Withnell and Brinscall now forms the Railway Park and can still be walked. Just before Brinscall was the siding for Withnell Brick Works and a siding for Abbey Village Cotton Mill. There is still a bridge at Brinscall that can be seen today and the cutting of the railway as it goes towards Heapey. Before Heapey the line passes the former R.O.F. site where there was a siding, and also one which intersected two of the Heapey reservoirs before serving Heapey Bleach Works. Half of the bridge carrying the line over Higher House Lane to the works is still in situ and just before Heapey there is a siding for Brinscall Calico print works.

The line continued under a bridge near Tithe Barn Lane towards the Blackburn-Chorley road, (again under an existing bridge) towards the Viaduct at Botany Bay, which carried the line over the Leeds Liverpool Canal towards Chorley. The line entered Chorley over bridges at Eaves Lane, Stump Lane and Brunswick Street to where Friday Street car park was and entered Chorley Stati.

The line died slowly, Doctor Beeching was making his plans and on 4th January 1960 the line was closed to passengers. Goods trains continued to use the line for the next six years, but when the line was made single track the traffic dwindled. Finally on 3rd January 1966 the line was closed to through traffic but a small section remained between Cherry Tree and Feniscowles for wood pulp for the Star and Sun Paper Mills until 1968 and at the Chorley end a section remained as a long siding as late as 1982.

My Father Frederick Booth was the Station Master from 1958 till 1968 when the station closed for good. I can remember when I was about fifteen my father gave me my one and only driving lesson in an old Austin van in the Goods Yard at Feniscowles, he wasn’t very patient with me, (never teach your relative to learn to drive!) There was a station house with the job at Feniscowles, but unfortunately it only had an outside toilet and we had just moved into a brand new house with an inside and outside toilet on the Higher Croft Estate, so my father turned it down. The Station house was then offered to the Signalman at Feniscowles, Alec Radnedge and his family lived in it until the 1970’s. My dad was Station Master at Mill Hill, Cherry Tree and Pleasington after Feniscowles closed, but they were phasing out Station Master’s so he left the railway and he became a Pub Landlord.

Some information was taken from an article by Steve Williams in the Chorley Guardian June 2007.

All photographs copyright Jeffrey Booth.

Researched and written by Jeffrey Booth. (library volunteer)

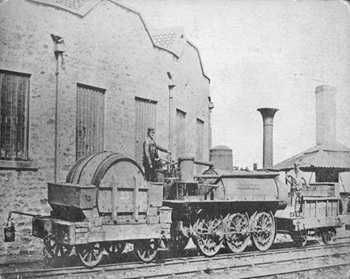

“Shannon” boiler explosion at Sough Darwen

On Friday the 19th of November 1846 at three o’clock, an explosion of the “Shannon” locomotive steam-engine took place on the works of the Blackburn, Darwen & Bolton Railway at a place called Sough, about three hundred yards from the Tunnel, by which one unfortunate man named Thomas Heaviside, an engine driver was blown a distance of fifty yards and killed instantly and another man John Waten, a stoker was forced under some waggons and very badly scolded. So violent was the force of the explosion that the boiler was blown out and the engine was blown into a thousand pieces and scattered near and far.

On Friday the 19th of November 1846 at three o’clock, an explosion of the “Shannon” locomotive steam-engine took place on the works of the Blackburn, Darwen & Bolton Railway at a place called Sough, about three hundred yards from the Tunnel, by which one unfortunate man named Thomas Heaviside, an engine driver was blown a distance of fifty yards and killed instantly and another man John Waten, a stoker was forced under some waggons and very badly scolded. So violent was the force of the explosion that the boiler was blown out and the engine was blown into a thousand pieces and scattered near and far.

The “Shannon “was an engine employed upon the line by the contractor to assist in the construction of the line.

On Monday afternoon at three o’clock an inquest was held at the “Millstone” public house before J. Hargreaves esquire. The jury was sworn in and viewed the body which was in a shocking state. The jury then went to the line at Sough to view portions of the boiler that were left, it was evident that the boiler had given way because of excessive explosive force. The first witness John Monday, a labourer who worked with the driver and the stoker. John was with the stoker on the front of the engine, the driver was on the rear of the engine and John jumped down to uncouple the wagons as the boiler exploded he threw himself under the wagon but when he looked round he couldn’t see his mates, someone told him the driver had been blown into the field. He went to find him, he had been blown fifty yards away and was obviously dead.

The driver was in charge of the water for the engine and the stoker was in responsible for the coal and stoking the boiler.

Witness Henry Rainford a mechanic employed for over twenty years in an iron-foundry said the cause of the explosion was a shortage of water. The flue has been red hot and that would not have been the case if there had been a sufficient supply of water.

Witness James Kenyon agreed with the last witness as to the cause of the explosion he considered that the Drivers negligence alone caused the explosion, the driver only should supply the water.

A verdict of “Accidental Death” was recorded by the jury.

A month before the explosion the engine was derailed by someone who placed an iron chair on the track, it was repaired and was in good condition

“Iron Chair"

Researched & written by Jeffrey Booth (library volunteer)

Information from the Blackburn Standard Wednesday 25th November 1846

Published February 2026

back to top