The Turnpike Era

From the early 1600s onwards, a gradual increase in trade between markets, ports and centres of production highlighted the deficiencies of Lancashire's road network. Turnpike Trusts were a reaction to this lamentable state of affairs, their original intention being to 'improve' existing roads although later Trusts built on entirely new lines. The idea was that after the initial financial outlay (raised as shares amongst the Trustees), the cost of improvement would be recouped by charging travellers a toll - the Trusts optimistically hoped that any additional monies raised could be used for the ongoing maintenance of the road. Despite the fact that their efforts were rarely rewarded financially, Turnpike Trusts did leave a legacy of improved roads. Being an important market and industrial centre ensured that several Acts were passed for road improvements around Blackburn:

Chronology of local Turnpike Roads (dates refer to passing of Act)

1755 Blackburn-Preston (Blackburn & Walton Cop Trust) - Preston Old Road

1755 Blackburn-Burnley (Blackburn, Addingham & Cocking End Trust) - via Rishton &c.

1755 Clitheroe-Preston (Skipton & Preston Trust) - via Snodworth Cross & Ramsgreave

1776 Blackburn-Whalley (Blackburn, Whalley & Clitheroe Trust) - Whalley Old Road

1789 Blackburn-Bury (branch of Bury, Haslingden, Blackburn & Whalley Trust)

1797 Blackburn-Bolton (Bolton & Blackburn Trust) - via Over Darwen

1808 Clitheroe-Mellor (Clitheroe & Mellor Brook Trust) - the Longsight Road

1810 Blackburn-Elton (Elton & Blackburn Trust) - Grane Road

1810 Livesey Branch Road (branch of the Bolton & Blackburn Trust)

1819 Blackburn-Whalley (Blackburn, Whalley & Clitheroe Trust) - Whalley New Road

1825 Blackburn-Preston (Preston & Blackburn Trust) - Preston New Road

1826 Blackburn-Accrington (branch of the Bury, Haslingden, Blackburn & Whalley Trust)

Generally, the 18th century Acts were concerned with the improvement of existing roads, while those of the 19th century often surveyed completely new lines of road. Good examples of local toll houses remain at Oaks Bar (SD670334), Finnington Bar (SD634251) and Moss Hall, now the Old Toll Bar Inn (SD704279).

By Nick Harling

In the days before Britain had an effective police force, crime was common on the roads and highways. In fact, the masked highwayman still lives on in the public imagination as a gentleman thief who preyed only upon the richest of travellers and who operated to a strict code of criminal honour. In many ways this view owes more to Victorian romantic literature than to reality - in truth, highwaymen were brutal villains who would think nothing of murdering a lone traveller for a few coins or a pair of boots, regardless of their wealth or social status.

Road crime is recorded as far back as Roman times and was certainly prevelant during the Dark Ages and the Medieval era. However, it was during the 17th century that the recognisable figure of the highwayman appears. In the wake of the English Civil Wars, many horsemen who had fought for the King found themselves dispossesed of their property and wealth - many decided to put their riding skills and pistols to a different use. Successful highwaymen such as Dick Turpin, John Cottington and Claude Duval became household names, even heroes to the general public, mainly because their targets were rich authority figures. But the many hundreds of unnamed 'footpads' who prowled the roadside verges were not so fussy about who they robbed.

By the beginning of the 18th century, the 'profession' of highwayman was in decline. Many of the big names pushed their luck too far and were caught, tried and hung. The gradual spread of the Turnpike system imposed a certain amount of order on Britain's roads - toll-keepers would report any suspicious characters to the local Parish Constable. Stagecoaches and Royal Mail coaches carried a 'guard', usually armed with pistols and a blunderbuss, for the safety of the passengers and their belongings.

In the face of this increased security, some highway robbers came up with ingenious schemes. Contemporary newspaper reports tell of burly felons dressed as women who booked all the inside seats on a stagecoach, then during the noisy journey cut through the seating to access the trunk in which the valuables were stored. At the next stop, the group of 'ladies' left the coach with their haul hidden beneath their skirts!

However, by the beginning of the 19th century, highwaymen had all but disappeared from Britain's roads and as banks became a more common feature of industrial towns, people no longer travelled any great distance with their valuables.

By Nick Harling

The Golden Era of Stagecoaches

The improved road surfaces of the turnpikes encouraged a development of efficient wheeled transport. The earliest passenger coaches of the Turnpike era were very primitive affairs and had little in the way of suspension. Accommodation for passengers was cramped inside, and those unfortunate enough to have booked an outside seat were obliged to sit directly on the roof with their legs dangling over the edge.

By the end of the 18th century coach design had been greatly improved with the introduction of sprung axles, lighter body construction, secure luggage boots and more comfortable seats. The main catalyst for this improvement was the introduction by the Post Office of fast coach services in the 1780s, designed specifically to speed up the distribution of the Royal Mail across the country. By the 1820s, a coach journey was not such a dreadful ordeal, providing that one had the money to secure an inside seat. On stage and mail coaches there were two classes of passenger, the 'insides' and the 'outsides', each coach being licensed to carry a certain number of each class. Both stage and mail carried 4 inside, with stagecoaches carrying up to 12 'on top'. Outside passengers were initially banned from mail coaches - later a maximum of 4 were allowed, so as not to jeopardise the faster timings and to protect the mail from the 'low types' who frequented the cheaper outside seats.

Coaching Inns

A unique product of the era were the coaching inns. They not only provided accommodation for man and beast, but also acted as stopping points for a network of timetabled coaches - a direct precursor of the railway system. Most coaching inns also provided 'posting' facilities for wealthier travellers, who could hire horses and post-chaise carriages. Blackburn had a number of large inns of this type, most of which have sadly now been demolished including the Old Bull and the Golden Lion (Church Street), the Eagle & Child (Darwen Street), the New Inn (Ainsworth Street) and the Bay Horse (Salford). Still existing in rebuilt form are the Hotel (King Street) and the Old White Bull (Salford).

Each inn was responsible for horsing coaches over an agreed stage, usually extending 10 to 15 miles in each direction. This was known as the 'ground' of the inn and was jealously guarded. When another inn began horsing a rival coach over the same ground the competition was stiff, with racing being a common occurrence and the cause of many fatal coaching accidents.

During the heyday of coaching, spanning the first three decades of the 19th century, Blackburn was relatively well served by both stage and mail coaches. The following selective list gives some idea of their names and destinations:

The Shuttle - to Burnley, Colne, Skipton & Halifax from the Old Bull

The Commercial - to Haslingden from the Old Bull

The North Star - to Liverpool from the Old Bull

The Vice-Chancellor - to Liverpool from the New Inn

The Umpire - to Bolton & Manchester from the Old Bull

The Invincible - to Burnley, Colne, Bradford & Leeds from the Old Bull

The Sociable - to Preston, Lytham & Blackpool from the Eagle & Child

The Hark Forward - to Whalley, Clitheroe & Skipton from the Old Bull

The Royal Mail - to Carlisle & Manchester from the Old Bull

The 1840s saw the stagecoach decline abruptly in the face of new railway competition. However, the romantic image of the stagecoach has endured, not least through the vivid descriptions of contemporary authors such as Dickens. As for the turnpike roads, they continued in operation for another 40-50 years, gradually being absorbed into the Lancashire County Highways division. Blackburn's final toll gate was removed from Shackerley Bar (Preston New Road) in 1890.

By Nick Harling

The photograph below arrived at Cottontown via Mr Stephen Child, former Deputy at Burnley Library. It shows the entrance to the Boulevard in the late 1890s.

The first horse bus ran up Preston New Road and there was a 15 minute service. By the early 1880s horse buses were well established. They ran to Accrington, Mellor, Witton, Intack and Oswaldtwistle, but only two or three services daily. They were single manned - passengers dropping their fare in a box. In winter there was straw on the floor.

How fortunate people were then compared to today's day-long snarl-up. No driving stress, just drop your coppers in the box and relax for a leisurely, if somewhat bumpy, ride.

The following item appeared in the Northern Daily Telegraph for March 22nd 1945 on page four.

Blackburn Arterial Road - the first modern road project

Road improvement was often limited to laying tarmacadam and occasionally widening the line of the road, although many primary routes remained (and sometimes still do remain) on the twisty course of the original turnpike. Inevitably, all through traffic was filtered through the town centre. The first modern road project designed to alleviate this problem locally was the 'Arterial Road', classified as the A6119 and comprising of Yew Tree Drive, Ramsgreave Drive, Brownhill Drive and Whitebirk Drive - essentially, a northern bypass for the town. The Arterial Road was opened on October 18th 1928; the introduction to the souvenir booklet gives a good indication of the road's function:

"The work on the construction of the Arterial Road was commenced in 1921, with two main objects in view. It was a suitable scheme for relieving the heavy amount of unemployment in Blackburn at that time, resulting from the Great War, and also from the point of view of relieving the congestion in the centre of the town, caused by very heavy traffic from Yorkshire and East Lancashire to the West Coast seaside resorts and to the North, by diverting this traffic around the east and North sides of the Town....The whole of the work including the construction of the bridges has been carried out by the 'Unemployed' men of the Borough so far as concerns the work in the Borough, and by 'Unemployed' men of Rishton, for the length of the road passing through the Urban District of Rishton. All men engaged on the work, with the exception of the foremen, were supplied through the Labour Exchanges".

Major engineering works included three reinforced concrete underbridges (two over railways and one over the canal) and brick and steel girder overbridge carrying the main railway line to Burnley at Whitebirk. Incredibly, no major earth-moving machinery was used in laying the line of the road - it was mainly carried out by large gangs of men with picks and shovels, and was described as 'bracing and healthy'! The total cost of the project was in the region of £155,000. Although the road's immediate effect was to ease town-centre traffic congestion, it also encouraged the development of housing schemes along its length. Indeed, nearly £5000 of the total budget was spent on providing branch roads for the new Brownhill Housing Scheme.

By Nick Harling

After the First World War, there was a gradual increase in motor-car ownership, although this was to a certain extent retarded by the inter-war years of depression. Nevertheless, more and more commercial carriers embraced the internal combustion engine and by the mid-1920s, it became clear that unless checked, traffic congestion intowns could become a problem in the future. This was particularly apposite in old settlements such as Blackburn, with narrow, winding streets, totally incapable of coping with large flows of traffic. In many respects, this is a problem which has never gone away.

The government began to get to grips with Britain's road problem in the early 1920s by classifiying roads according to their function. Long distance trunk and primary routes became A-roads, urban and rural cross-routes becoming B-roads. Minor streets and lanes remained unclassified. Former turnpike roads usually became A-roads. The main routes serving Blackburn and Darwen were the A666 (former turnpike to Bolton and Manchester) and the A59 (the Preston to Skipton turnpike). The main roads to Burnley and East Lancashire became the A678 and A679. Roads were numbered according to the 'zone' in which they began. Therefore, A-roads beginning with a number 6 started west of the main A6 trunk road.

The Preston Bypass

After the Second World War a gradual upturn in Britain's prosperity saw private car ownership increase at a far greater rate than the road system was being improved. In particular, long distance lorries were forced through inappropriately narrow town centre streets. A plan to begin a programme of motorway construction had been under consideration by the Government since before the War - they had been impressed by Germany's system of Autobahnen - but it was only after hostilities had ceased that planning began in earnest. One of the greatest advocates of motorways was Lancashire County Surveyor, James Drake. It can be no coincidence, therefore, that the Government approved a plan for Britain's first motorway to be constructed in the county. The Preston Bypass was constructed between Samlesbury and Broughton, opening in December 1958. It became the first part of the M6, a major route that would eventually link Birmingham and Carlisle. The M6 had a profound effect on the local area. Improvements were made to the A677 and A59 trunk roads which linked Blackburn to the new motorway. As the M6 was gradually extended, businesses in East Lancashire could boast that they had better national connections than rivals in other parts of the country.

M65

As the M6 neared completion, it became clear that East Lancashire's economy would be boosted even further if a motorway link was provided which connected the towns of the Calder and Darwen valleys to the national network. The North east Lancashire Project Study of 1969 recommended the construction of a route between Colne and Blackburn, with the possibility of extending westwards to a connection with the M6. The route was opened in stages between 1981 and 1997, the final section being the Blackburn Southern Bypass, by which time the 'anti-roads' lobby had gained enough impetus to stage demonstrations and sit-ins at Stanworth Woods, illustrating how attitudes towards roadbuilding had changed since the previous decade. The M65 was the last full-scale motorway to be completed in Britain.

By Nick Harling

The old road bridge spanning the railway sidings on Freckleton-street was of an Edwardian construction, built of iron. It was a four-span bridge which was restricted to single lane one-way traffic and was assessed as sub-standard, the maximum weight for the bridge was only 17 tons.

In 2007 the old bridge was demolished as part of a scheme to make an Orbital Route around Blackburn. The planed new bridge would link Bolton-road to Barbara Castle Way.

The new bridge is a “single span 79m span steel bowstring arch with a steel/concrete composite deck carrying a dual carriageway. The footways are carried on cantilevers from the arch ties and tubular twin arches are situated at each edge of the deck. The substructures are made of reinforced concrete construction on piled foundations.

The Total cost of the project was £12,000,000. The Chief engineer was Faris Samin, of Capita Symonds, and the contractors were Balfour Beatty Civil Engineering.

The bridge was named Wainwright [the famous fell walker / author Alfred Wainwright who was born in Blackburn] after a vote taken by Lancashire Telegraph readers.

The new bridge was opened on the 27th June 2008 by local MP Jack Straw assisted by John Burland, the Press and Publicity Officer of the Wainwright Society. The first people to cross the bridge were pupils from St. Anne’s RC Primary School, Feilden-street, Blackburn who cycled across it.

It was hoped that by 2009 the final link of the Orbital Route could be completed, this would run from the Wainwright bridge to Montague-street there joining with Barbara Castle Way but up to 2013 this as not been done.

Acknowledgements.

Capita, Lancashire Telegraph, The Wainwright Society.

© BwD - terms and conditions

back to top

At the 1996 AGM of the Blackburn Local History Society, Mr. Fred Gemmell expressed an interest in the 'street furniture' of Gorse Road. Fred had lived in Gorse Road for forty years, most of the time at no. 42, and latterly at Birchfield House. He did not feel that he could follow it through by himself so I volunteered to help. I had to admit though, that I was totally ignorant of the meaning of 'street furniture'.

We reconnoitered the area one afternoon and I learned that street furniture meant gates and gateposts, porches, balconies, railings etc. Fred was primarily interested in the eight semi-detached Victorian houses, but also the 'infills' - houses which have been added to the road during the twentieth century.

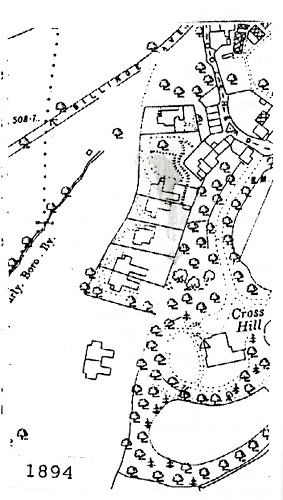

A study of a map of 1848 shows that what is now Gorse Road was once a field among many fields reaching from Billinge End Brow to Redlam Brow. As the land is adjoining Witton Park, I presume it belonged to the Feildens. One of the residents has confirmed this. Among his papers it is recorded that on 1st February 1893, a conveyance of land was made from Randle Feilden to Thomas A. Aspeden, who built several houses on Gorse Road. Perhaps the name of the road came from its close proximity to the Yellow Hills. A look at the 1891 census revealed that there were no houses on Gorse Road at that time. I then had the idea of checking the minutes of Blackburn Borough Council, which are in the Reference Library.

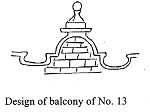

In 1891, George Higson applied to the Highway Committee for planning permission to build a house on Gorse Road. I think this must refer to no. 13, Brookfield as George Higson or members of his family, lived there until 1958. The house is detached and built in red brick and cream stone. The gateposts are topped with stone balls as are the very attractive brick and stone balconies at the upper windows.

During the next few years planning permission was requested to build more houses - May 1891 by Mr. J. Walsh; November 1891 by Mr. Thomas A. Aspden; May and June 1893 by Mr. Jos. H. Walsh and April 1894 by Mr. T. A. Aspden. All the eight Victorian semi-detached houses have porches, the original ones appear to have been built half brick with timber upper walls, and with windows and tiled roofs. The porch of no. 19 has been rebuilt with white pseudo-Roman pillars and a flat roof. The owner of no. 23 had to rebuild his porch in a more modern style when it was demolished by a falling tree during a storm.

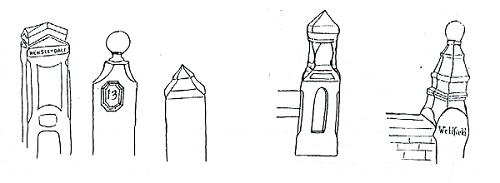

The original and most common ones appear to resemble a pawn in

a game of chess (The Willows, Wellfield, Lancrigg and Edenholme).

Nos. 17 and 19 have a different style of gatepost, and no. 23 has

lost its original post as well as its porch and overall has a more

modern design.

Several of the houses have undergone name changes over the years. Number 15, Royle, now named Lothlorian, was St. Silas' vicarage until 1941. It then became St. Mark's vicarage until the present one was built next to the church in Buncer Lane.

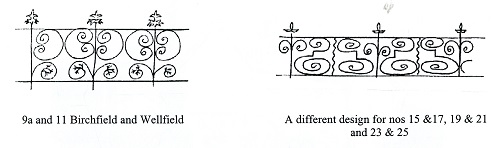

None of the houses appear to have possessed railings, if the evidence of the stonework of the outside walls is any guide. All have lost their original gates, presumably during the second world war salvage drive. No. 17 (Wensleydale) is the only Victorian house with a gate at present. It was erected by the present owners in 1965 to prevent their children from running out into the road. Each Victorian semi is joined to its neighbour by a wrought iron balcony at the upper central windows. The inaccessible position of the balconies probably saved them from joining the gates to help the war effort.

Birchfield, where Fred Gemmell lives, has an interesting history. It was originally called The Willows, with its name on the pawn-shaped stone gatepost and willow trees growing in the garden. In 1979 the occupier of The Willows built a modern house in the garden and moved into it, taking the name, house number and gatepost with him. The old house became 9A and was renamed Birchfield. In 1985 the house became a residential home for the elderly.

Over the front door, above the post is a stone plaque. As far as I can make out, the initials appear to be MR and I or T. Up to the present time I have not been able to find out what they stand for. It has been interesting to follow the houses and those who lived in them through Barratt's Directory and the Electoral Roll.

At the top of Gorse Road is a terrace

of three houses, nos 1, 3 and 5 which

appeared at the beginning of the last century.

The design of their gateposts, the Star of David,

is repeated outside a row of houses on St. Silas'

Road, opposite Sacred Heart School

The first modern house to be built on the odd numbered side of Gorse Road appeared in 1924. This was no. 27 and named Wendover. No. 25A was the first 'infill' and appeared in 1975. Modern wrought iron railings decorate a bungalow, no. 17a, which was built in 1977. The new Willows has been mentioned already, and appeared in 1979. The last 'infill' was built in 1992, a block of four flats between 25 and 25A, and named Gorse Mount.

One family has lived in Gorse Road even longer than the Higsons, 100 years in fact. The first occupant of no. 21, Lancrigg, was Charles Marsden, a solicitor. The last family occupant was Charles' nephew, Carl Marsden, who died there in 1993. The previous Christmas, Mr. Marsden had sent his friends and neighbours a Christmas card showing what the house looked like when first built. The picture is interesting in that it shows the original gates and gateposts.

In September 1991, the BBC brought their own 'street furniture' to Gorse Road. Filming was taking place of 'The Likely Lad' for children's television. Lancrigg became Laurel Villa and wrought iron gates were added for the occasion. A more authentic Victorian setting was created by the addition to the road of plastic setts

Acknowledgements - Many thanks to Blackburn Reference Library for access to records and maps.

Barbara Riding

Published 2024. The original article was published in the Blackburn Local History Society Journal of 2000-1. page 4

back to top